My dog Shadow is a barkaholic. If there were a 12-step program for such a condition, she would be a good candidate to attend. She likes to bark when she is happy and excited, when she is concerned, when she would like something from us, when something surprises her, when other dogs bark, and mostly, when squirrels run through the trees in our backyard. The squirrel bark is the worst – sharp and shrill and so loud that it makes your ears hurt. Now, how to stop a dog from barking? Well, like Shadow many dogs have their reason(s) to bark.

The trouble with having a dog who barks for a variety of reasons is that there isn’t one easy answer for getting her to stop. People often see barking as a single problem; just last week I was asked by several students in my class, “How do I stop my dog from barking?” I couldn’t give a simple answer. The solution to barking problems depends on understanding several factors:

1. When and where is it happening?

2. Why is it happening? What is the specific trigger?

3. What is the dog getting out of barking? What is reinforcing the behavior?

And if your dog, like mine, barks in several different situations, has multiple triggers, and the reward varies, you may need more than one solution to help your dog live a quieter life. But once you can identify the when, where, why, and what, you can come up with a training plan to solve the problem.

Different Reasons, Different Solutions

Remember that barking is normal behavior for dogs. It is a form of communication. Most dogs bark some of the time and often for very good reasons. Here are some of the most common:

They are excited! There are many potential triggers for excitement barking. Perhaps your dog barks when you first come home or when a friend comes to the door. Dogs who bark when they are excited may bark in play, or when they see something they like, or when they are amped up for no apparent reason.

They want something. This is often called demand barking, but in my house, we call it bossy barking. I live with herding dogs and they do tend to take charge. “Hey, don’t you know it is time for a walk?!”

Demand barking is also common when training with food – when dogs get frustrated because the treats aren’t coming fast enough, for example, they may bark to remind you to keep the food flowing. Barking is also one of the ways that dogs have to ask for what they want or need. A dog may bark when she needs to go outside to potty, and this may be a very good thing!

They are alerting to something. Most dogs alert-bark to some degree. They may bark when someone comes up to the house, or when there is an unusual noise, or when another dog in the neighborhood barks.

Most of us appreciate some degree of alert barking (for example, I’d be very happy with my dog if she barked if someone were trying to break into my house). The problem with alert barking comes when our dogs are barking at things that people think are inconsequential or when they continue barking when we think they should stop.

They are afraid. We all have things that scare us and so do our dogs. Recently, I was walking with my dog on a familiar path, a place we walk almost daily. As we came around a bend, there in the middle of the path was a pile of boulders. My dog was so surprised by this new thing in our path that she became very afraid -and barked like crazy.

This type of startle barking is relatively common in adolescent dogs like Shadow. Once she stopped barking, we went and investigated the boulders and she realized they were just rocks and all was good. Some dogs, however, have more significant fears – they may be afraid of men, or kids, or other dogs, or hats, or skateboards. When a dog barks because of an ongoing fear, that fear will need to be addressed before the barking problem can be solved.

They don’t do well when alone. Many dogs will experiment with barking when they are alone and bored. Maybe they bark at the squirrels or the neighbor’s dog. Boredom barking often has elements of alert barking, excitement barking, or demand barking. But barking when home alone can also be a symptom of separation distress or anxiety. When dogs are barking when home alone, we need to figure out why in order to effectively help our dogs.

How to Stop a Dog from Barking!

Once you have identified why your dog is barking, you can follow these steps to solve the problem:

1. Management first.

Management means finding ways to prevent your dog from barking while you are working on changing the behavior. Your management steps will vary depending on your dog’s trigger.

For example, if your dog barks each time someone walks by the front of the house, you may need to block the dog’s view of the street with window coverings or plan to have the dog in the back of the house when you aren’t actively training.

For a dog who barks when scared, you may need to avoid those things that make your dog afraid while you work through a behavior modification plan. For a dog who barks when playing with his pal, you may need to interrupt the play often so that the dogs don’t become quite as excited. These are all forms of management.

2. Change your dog’s reaction to the trigger.

Sometimes solutions to barking problems are as simple as changing your dog’s relationship to the trigger (notice I said simple, not easy!).

So, for example, if your dog barks excitedly when you come home from work, you may find success with being a little less interesting when you first come home. If you (the trigger) become less exciting, your dog will be less likely to bark. For a dog who is afraid of men, embarking on a counter-conditioning program with a qualified trainer may help solve the problem. When the fears are alleviated, the barking will likely stop on its own.

3. Teach an alternative behavior.

This can be a key component in solving barking problems. What else can your dog do instead of barking (and the answer can’t be “not barking”)? Here are some ideas: If a dog barks at other dogs on a walk, you can teach her to look at you and get a treat each time she sees another dog. If a dog barks at the front window, you can teach her to run and find you in the house rather than bark. If a dog barks in excitement, you can teach her to grab a toy and play when excited. If a dog barks to get you to take him for a walk, you can teach him to sit in front of you to remind you it is time to go out instead. With enough practice, those things that previously triggered your dog to bark will now trigger the alternative behavior instead.

4. Change the consequence.

Let’s face it, most barking is intrinsically rewarding to the dog. A dog barks when someone walks by the house, the person continues walking – and the barking is reinforced by the person going away. Your dog barks at you for attention, you turn around and ask him to stop – and the barking is rewarded by your attention, even if it is scolding.

Changing what happens after he barks can impact his barking in the future. For example, if your dog barks at you for treats, putting the treats away instead of giving him one may be part of the solution.

As another example, if a dog barks when he sees his best pal, you may help him learn that approaching quietly means he will have the opportunity to say hi or to play – and that barking as he gets closer causes you and the other dog’s owner to part ways, ending his opportunity to play.

5. Teach an interrupter.

You can teach your dog a “quiet” cue that can interrupt a barking cycle. The key to teaching this is to do it when the dog is not barking, rather than trying to teach it when the dog is already barking.

When your dog is already being quiet, say “Quiet,” mark it with the click of a clicker (or another marker, such as the word “Yes!”) and then reward your dog. Once your dog hears the word “Quiet” and starts orienting to you in expectation of the treat, switch to marking and rewarding the orientation.

Once you’ve practiced a few dozen times, you can give it a try when your dog is barking – preferably, a low-key sort of bark (don’t start when she’s about to lose her mind over a squirrel on the sidewalk right in front of you!). Say “Quiet!” and then when your dog glances at you, mark (click or “Yes!”) and give her a tasty treat.

Teaching a “Quiet” cue will seldom completely solve a barking problem, but it can interrupt the barking long enough for you to direct your dog to do an alternative behavior.

6. Help your dog learn to be calm.

Barking is almost always coupled with overexcitement. A dog engaging in a calm activity is less likely to bark than a dog engaged in an arousing activity. While helping your dog learn to be calmer isn’t directly addressing barking, it can have a big impact. You can help your dog learn to be calmer by:

– “Capturing” calm by rewarding your dog when she is already settled.

– Teaching your dog to settle on a bed or mat.

– Practicing impulse-control exercises can help a dog focus when excited. Examples of these exercises include tug-sit-tug, down before ball tosses, and asking her to sit and wait quietly before you put her food bowl down.

– Providing low-key exercise and activity rather than lots of ball or chase games. Often when we have easily overstimulated dogs, we want to wear them out with activities such as fetch or dog-to-dog play. While these are great activities for many dogs, they can also wind dogs up – and amped-up dogs are much more likely to bark. Long leisurely walks or scent games can tire your dog without getting her overexcited.

7. Be realistic.

Dogs bark. Barking is perfectly normal behavior and not something that is likely to be eliminated completely. For example, instead of expecting your dog not to bark at all when people come to the door, consider allowing a few barks, and then giving the cue (and rewards) for quiet. And if your dog barks out of fear or anxiety, remember that those issues must be addressed before you can realistically expect your dog to stop barking.

Just Say No to Bark Collars, Air Horns, Squirt Bottles, and Other Punishments

There are several reasons I don’t use this type of punishment for barking.

First, I don’t like to do anything to my dog that is intimidating or that causes pain or fear. Shock collars work by creating pain, noisemakers such as air horns work by scaring the dog, citronella collars and squirt bottles work by startling the dog or creating an unpleasant sensation. I do not want to do any of these things to my dog.

Also, I don’t think they are particularly effective in most situations. I will confess that in my distant past, I have used all of these in attempts to curb barking behavior. While I sometimes saw a short-term change in the behavior, in the long run the barking always returned. (And the few times I have seen punishment effectively stop barking, a kinder choice would have worked as well.)

Finally, the fallout from using these devices can be significant. Shock collars can cause aggression issues, noisemakers can add to startle and sound issues, and squirt bottles can make your dog want to avoid you! Enough said.

What About Timeouts?

A timeout works by taking away the opportunity for reinforcement. I am not a huge fan of timeouts. They are difficult to do well and are often used unfairly, creating unnecessary frustration or stress for the dog – and are totally inappropriate for a dog with separation anxiety. However, I will very selectively use timeout for one type of barking – demand barking – but only after other criteria have been put into place.

In my opinion, it’s unfair to use a timeout for a behavior before a dog has been taught an alternative response – in this case, something he can do instead of barking to ask for what he wants. If your dog barks to go outside, you can teach him to ask with a gentle nose nudge instead. For dogs who bark to get you to play, teach the dog to bring you a toy instead of barking. For dogs who bark to demand treats, teach “settle” as a default behavior when food is present.

In addition, before using a timeout, dogs need to understand an “all done” cue – something that lets them know that the opportunity for whatever reinforcement they want is no longer available. “All done” means there is not a chance that they can get the reward they are looking for.

Once the dog understands that another behavior can get him what he wants and he understands that sometimes he cannot have what he wants, only then, if it is still necessary, I will use a five- to 10-second timeout to let the dog know that barking is not an acceptable way to ask for what he wants. Here’s how it works:

– When my dog wants to play, she can go grab a toy. When she brings me a toy, I immediately engage with her. (This is especially important when you are first teaching your dog an alternative response – it has to work for her, too!)

– If, instead, my dog barks to get me to play, I mark the second the barking starts by saying calmly, “Too bad!” and I get up and walk into another room and close the door. I return in five to 10 seconds (assuming the barking has stopped). If my dog barks again, I repeat. If my dog grabs a toy, I play.

– If my dog comes and asks me to play and I cannot at that moment, I will give her the “all done” signal so that she knows that playing isn’t an option at that moment. But I will take note that she needs some attention and will give it to her as soon as I can.

If a timeout is done well, you will generally see a dramatic reduction in barking in just a few short training sessions.

Back to the Barkaholic

Unfortunately, many dogs who bark excessively do so in more than one area. This means that you have to get creative and proactive to help your dog learn to live a quieter life.

Following the multi-step approach above, we came up with a training and behavior modification plan for my barkaholic, Shadow. Remember that she barks when she is excited, in response to other dogs barking, when she is startled, when she wants something, and at the squirrels in the yard, and more recently as she’s grown up, alert barking has joined the list. Basically, she was barking almost all the time!

To reduce her excitement barking, my partner and I worked with her to be overall calmer and more focused in a variety of situations. Some of the exercises we are using to do this include impulse-control games, settle exercises such as mat work, and counter-conditioning specific triggers to reduce excitement.

For her alert barking, we taught alternative responses like redirecting to us when she sees or hears something that she would ordinarily bark at, such as another dog barking or the neighbor’s car door slamming.

For her startle barking, we are using straightforward classical conditioning; things that surprise her make treats rain from the sky!

For demand barking (such as for treats or attention or a ball toss), we have taught her to ask in other ways (by bringing us the toy, for example, to solicit play).

Because barking at the squirrels had elements of excitement, alerting, and demand barking (she would bark to make the squirrels run across the treetops), we’ve had to get very creative.

First, we employed management by limiting her access to the yard and by blocking her view of the squirrels through the windows. We also kept her on leash in the yard when we went outside together at the beginning of this training.

I worked with Shadow to be calmer around the squirrels by doing basic obedience and mat work at a distance from “the squirrel trees,” then gradually moved closer until she could respond when we were near those trees.

Also, I have been teaching her to come to me, away from the squirrels. We started at a fair distance from the trees and are slowly moving closer and closer to the trees to work on this. When she sees a squirrel, she now runs to me for huge rewards – and this has helped reduce her fixation. We also use brief timeouts if she did start barking.

By employing all of these techniques, Shadow has gone from being a dog who barked in most situations to a dog who only very selectively barks and who is learning to bark less and less every day. Her barking is overall about 80 percent better, a huge improvement!

I have to admit that it has been a lot of work and has taken about six months to get to where we are today – from non-stop barking all day long to a dog who only barks occasionally and mostly appropriately. It is a work in progress, but the effort is totally worth it because we will now have many, many years of a mostly quiet life together.

Mardi Richmond is a dog trainer, writer, and the owner of Good Dog Santa Cruz, in Santa Cruz, California.

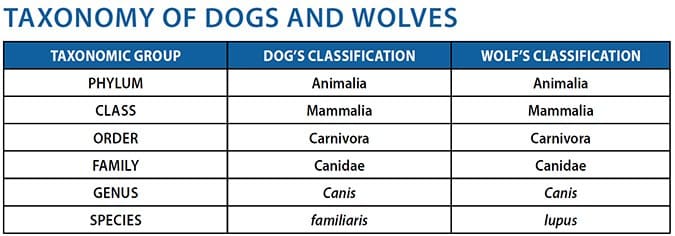

Cousin, Not Ancestor

Cousin, Not Ancestor