By the time they’re three years old, most American dogs have an active dental disease, and its treatment can be expensive. Dog dental insurance might save thousands of dollars in dental care, but if your dog never needs a dentist, you could pay hundreds of dollars every year for insurance you never use. Or your insurance plan might not cover your dog’s treatment. Is canine dental insurance worth the cost?

How Dog Dental Insurance Works

Dental insurance for dogs is not sold alone. It’s sold as part of a comprehensive illness-and-accident pet insurance policy.

In most cases, you pay for veterinary services when they are performed, then submit a claim with itemized receipts to your insurance company for reimbursement. Dental coverage is subject to waiting periods specified in the pet insurance policy, usually between 2 and 30 days before a treated condition is eligible for reimbursement.

Pet health policies do not cover pre-existing conditions, so it makes sense to enroll at-risk dogs before they develop gingivitis or periodontal disease.

What Dog Dental Insurance Covers

Most canine dental insurance plans cover:

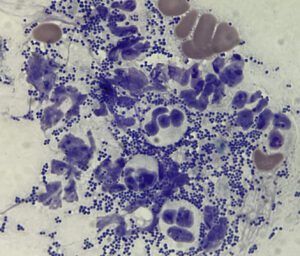

- Treatment for periodontal disease, gingivitis, oral tumors, and stomatitis (inflammation of the mouth).

- Emergency procedures such as treatment for illnesses and accidents including tooth extractions, root canals, X-rays, and prescription medications.

- Treatment of fractures and other trauma injuries to the teeth and jaws.

Basic illness-and-accident policies do NOT cover the following, but they may be provided for in an add-on wellness policy:

- Annual dental exams

- Routine tooth cleaning

- Dietary supplements and dental chews

Dental coverage in an illness-and-accident policy requires:

- Annual dental examinations

- Following your veterinarian’s specific recommendations for routine care

Annual Exams and Tooth Cleaning

Illness-and-accident policies that include dental coverage do not usually pay for annual exams or tooth cleaning unless they are part of the treatment plan for a dog who developed dental disease after being enrolled. Dental exams and tooth cleanings are preventive measures, and in most cases those expenses are covered or partially covered by optional add-on wellness policies.

Understanding Insurance Policy Terms

Every policy that pays for illnesses, accidents, and dental procedures for dogs will define the policy’s:

- Annual limits (maximum payouts per year)

- Reimbursement rates (such as 70% or 90% of eligible veterinary expenses, up to the policy’s limit)

- Co-Insurance (the difference between the reimbursement rate and 100%, which is your responsibility)

- Annual deductible rates (the amount you pay for covered conditions before being reimbursed)

What You Will Pay for Your Dog’s Dental Treatment

If your insured dog is in an accident or becomes ill, you are responsible for paying the policy’s deductible, plus your co-insurance percentage of remaining eligible expenses, plus any veterinary treatment fees exceeding the policy’s annual limit.

What Factors Affect the Cost of Canine Dental Insurance?

Monthly premiums for dog dental insurance depend on:

- the type of coverage and its limits

- the dog’s breed and age

- the dog’s health condition

- location (city and state)

- the insurance provider and its underwriting criteria

- deductibles and reimbursement rates

- optional add-ons, such as wellness care plans

- discounts for insuring multiple pets and in some cases registered service or therapy dogs or the owner’s military service.

Dental Insurance and Dog Breeds

Some breed-specific factors can affect dental coverage. Breeds with potentially higher dental insurance costs include small and toy breeds such as Chihuahuas, Yorkshire Terriers, Pomeranians, Maltese, Toy Poodles, and Shih Tzus, which often have crowded teeth in their small mouths, leading to plaque buildup and gum disease; brachycephalic (flat-faced) breeds such as French and English Bulldogs, Pugs, Boxers, and Boston Terriers, whose compact skulls can overcrowd teeth; and breeds prone to periodontal pockets, tartar buildup, and gum disease such as Dachshunds, Shetland Sheepdogs, Greyhounds, and Cavalier King Charles Spaniels. These dogs as well as Great Danes, Newfoundlands, and Irish Wolfhounds tend to have the high health insurance premiums.

Dental Insurance and Dog Age

The cost of dental procedures varies by location, the dog’s overall health, and age. Some companies do not insure dogs above a certain age, and the cost of coverage increases with age.

Is It Worth Buying Dog Dental Insurance?

Consider how an unexpected bill for your dog’s dental problems, illness, or an accident could affect your family’s finances. For example, treating periodontal disease or gingivitis can cost between $300 and $1,000. Simple extractions average $35 to $75 per tooth and most root canals cost between $1,000 and $3,000. Advanced oral surgery can be even more expensive.

According to organizations that track pet health expenses, the average vet visit for dogs in the United States is under $200. If your dog remains healthy and accident-free, the monthly premiums for pet insurance will quickly exceed the cost of routine checkups. But if your dog is injured or becomes seriously ill, his treatment can cost more than many pet owners can afford. Finding a balance between the risks your dog faces, insurance that covers those risks, and what you can afford requires research, but it doesn’t have to be daunting. The most common conditions treated by veterinarians involve dental illness, so if your dog is likely to develop tooth or gum problems, focus on the details of insurance policies that include dental care.

Comparing Canine Dental Insurance Plans

Thanks to their interactive websites, it’s easy to compare the policies and rates of leading pet insurance companies. Do this by visiting insurance websites and entering your dog’s breed, age, location, and other requested information. In addition to focusing on included dental procedures, study everything the policy covers and doesn’t cover. Most insurers will provide a sample policy for your review. Every insurance company invites prospective clients to connect with them by phone, chat, or email with questions about their plans.

Trupanion Pet Insurance from State Farm offers basic policies for dogs up to 14 years old that cover treatment for new dental illnesses and injuries, such as tooth extractions, caps, crowns, root canals, jaw fractures, tooth repairs, root abscesses, and tooth resorption. The policy does not cover pre-existing conditions, routine dental cleanings, or preventive care. The insurance reimburses 90% of eligible expenses after a lifetime (one-time) deductible has been paid for the condition. Trupanion pays veterinary fees directly to clinics at checkout (no reimbursement application needed) and there is no reimbursement maximum (no per-incident, annual, or lifetime limits).

Fetch Pet Insurance covers dental treatments for dogs regardless of age. Its dental coverage includes treatments for periodontal disease, oral tumors, fractured teeth, root canals, crowns, gum disease, tooth resorption, tooth extractions, and gingivitis. Pre-existing conditions, cosmetic and orthodontic procedures, including implants, fillings, and caps, are not included. Routine dental cleanings, which are not in the standard plan, are covered in a Fetch Wellness add-on. The standard policy has an annual limit of $5,000, annual deductible of $500, and 70% reimbursement rate.

Spot Pet Insurance covers dental expenses in its basic illness-and-accidents policy. The annual limit for illness and accident claims is $2,500, and the policy covers 70% or 90% of eligible expenses with deductibles of $250 or $500. An add-on wellness plan covers annual dental cleanings.

Pets Best Pet Insurance from Progressive covers dental emergencies, periodontal disease, extractions, and endodontic treatment for canine and carnassial teeth with its basic illness-and-accidents policy. There is no annual limit (maximum payment) to coverage. The basic policy has a $500 deductible and 80% reimbursement rate. An add-on policy covers dental cleanings.

ASPCA Pet Health Insurance covers tooth extractions for dental accidents, treatment for conditions like gingivitis and periodontal disease, and tooth cleanings prescribed for dental diseases in its basic policy. It does not cover cosmetic procedures. The website offers different combinations of annual limits, reimbursement rates, and deductibles, such as limits of $2,500, $5,000, $7,000, or $10,000; 70%, 80%, or 90% reimbursements; and $500, $250, or $100 deductibles. A Basic Preventive Care add-on policy covers preventive tooth cleaning.

Figo Pet Insurance provides dental coverage in its basic illness-and-accident policy, which covers expenses for the treatment of dental illness or accidents. Its most popular policy has a limit of $10,000, $750 deductible, and 70% reimbursement rate.

An optional Basic Wellness plan covers annual tooth cleanings.

Embrace Pet Insurance covers periodontal disease, abscessed teeth, misaligned teeth, gingivitis, tooth loss, jaw fractures, oral trauma, and tooth fractures in its illness-and-accident policy. Options include policies with annual limits of $5,000, $8,000, $10,000, $15,000, or unlimited; deductibles of $100, $250, $500, $750, or $1,000; and reimbursement rates of 70%, 80%, or 90%. A Wellness Rewards add-on program covers preventive dental cleaning.

Odie Pet Insurance includes dental care in its basic illness-and-accidents policy, which does not cover pre-existing conditions except for those that were cured at least 18 months before applying. Beginning at age 3 for periodontal disease coverage, teeth must be annually cleaned and examined under general anesthesia and any periodontal disease found during the exam must be treated before periodontal disease coverage becomes available. The basic policy pays up to $10,000 (annual limit) reimbursing 90% of veterinary fees with a deductible of $500. A Wellness Plus add-on plan covers annual tooth cleaning.

Pumpkin Care Health Insurance offers an illness-and accidents policy that covers dental illnesses such as periodontal disease and gingivitis and other dental procedures. It does not cover pre-existing conditions or dental cleaning except for dogs with active dental disease. Not covered are routine dental cleanings for dogs who do not have an active dental disease, caps, crowns, root canals, fillings, implants, or planing, even when related to periodontal disease. The most popular plan among its several options has an annual limit of $10,000 with a $500 deductible and 90% reimbursement rate. A Preventive Essentials add-on wellness plan covers dental cleaning.

Prudent Pet Insurance includes dental procedures in its basic illness-and-accidents policy, which has several options. The most popular has a $10,000 annual limit, $500 deductible, and 80% reimbursement rate. Annual cleanings are covered under a wellness add-on policy.

Lemonade Pet Insurance is available in only 38 states. Its basic illness-and-accident policy, which pays a maximum of $5,000 per year after a $250 deductible for 80% of covered claims, does not cover dental procedures. A Preventive+ add-on wellness policy includes routine dental cleaning and dental illness diagnosis and treatment, such as tooth extractions, root canals, gingivitis, and periodontal disease.

Accident-Only Policies

Some insurers offer inexpensive stand-alone accident-only policies that cover exam fees, diagnostics, and treatments for new injuries and emergencies related to accidents, such as bite wounds, cuts, broken bones, lodged foreign objects, and toxic ingestions. These are not dental policies, but they do pay for treatments to teeth injured in accidents. Accident-only policies are offered by ASPCA, Pets Best, Spot, Embrace, and Prudent Pet Insurance.