It’s not uncommon for humans who are living with young dogs to bemoan the adolescent “wild child” phase of development – when the canine youngster naturally starts becoming a little more independent and, sometimes, a lot more active. Of course, dog personalities lie on a continuum from very calm to quite energetic. Some even display excessive jumping and biting as young puppies. If you’ve previously had the good fortune of only raising dogs at the calmer, naturally well-behaved end of the continuum, you may think they are all supposed to be like that – and it can be particularly alarming to discover you’ve adopted one at the high-arousal end of the continuum.

I had two clients recently with remarkably similar concerns about their dogs – one, a seven-month-old male Golden Retriever, the other a 13-month-old neutered male Labrador. Both of these adolescent canines are from hunting lines, which means that they are at the high-energy end of the range of sporting-breed personalities. Both families described dogs who were “out of control,” biting and jumping in an aroused fashion when greeting people. Both families had sought advice from other professionals prior to coming to me; one dog had experienced only force-free methods, while the other had been on a prong collar and subjected to forced restraint and being “put on the ground.”

It came as no surprise to me that the behavior of the force-free dog was improving, while the dog who was being forced to the ground was starting to offer an escalating level of aggression in response. Time and again, we see dogs become defensively aggressive when their humans use confrontational methods.

High-Energy Dogs: Normal, But Not Desirable

I commended the first owner for pursuing a force-free approach to working with her dog, and the following day, counseled the other as to why we needed to take force and coercion off the training table. I explained to both families that they were seeing normal behavior in dogs who were bred to spend hours running through the woods, accompanying hunters in their quest for game birds.

“Normal,” of course, doesn’t necessarily mean acceptable. Both dogs need significantly more physical exercise and mental stimulation to meet their genetically programmed exercise needs, as well as a ramped-up management plan to prevent them from being reinforced for the unwanted behaviors.

I have fostered several dogs with similar high-energy behaviors, and without exception, every one of them was significantly helped by our standard exercise protocol for such dogs: a minimum of three off-leash hikes around the farm every day (or on a long line, if not trustworthy when off leash). I explained to both clients that the two on-leash walks their dogs were getting each day were just an exercise hors d’ouerve – an exercise appetizer for dogs like these. Of course, not everyone has access to an 80-acre farm they can hike on – hence the need to find other creative exercise alternatives.

Off-Leash Play for Excess Energy

Without access to a farm, you’ll need creativity to find exercise alternatives for your high-energy dog. A fenced backyard can be a terrific ally in your quest for exercise options, but don’t think you can just turn your dog out in the yard and leave her to her own devices. You may think your dog is self-exercising in the backyard, but in reality she’s probably spending a lot of time lazing in the sun, with perhaps an occasional burst of energy if a hapless squirrel or bunny wanders inside the fence. If she is running a lot, there’s a good chance it’s a high-arousal fence-running frustration response to stimuli outside the yard, which only contributes to high-energy inappropriate behaviors.

Instead, play with your dog! Here are a number of off-leash games that are perfect for tiring out dogs who otherwise have a bit too much energy:

Fetch

The aforementioned sporting breeds are usually more than willing to retrieve, over and over and over again. Yes, they do have a genetic predisposition to chase things and bring them back – that’s why they are called retrievers! The herding breeds, also generally high-energy dogs, are also genetically predisposed to bring things back to you.

If your dog will chase things but not bring them back, or brings them back but won’t give them to you, you can play the multi-ball game. Have a bucket of balls, and each time she chases one and dances out of reach with it, pick another out of the bucket and hold it up. Most dogs will drop the one they have in order to chase the next one you throw. Collect the one she dropped for the next throw, or just keep picking balls out of the bucket to throw, and collect them all after the game is over.

If your dog will bring them back, but plays body-slam-and-grab when she reaches you, play the bucket-of-balls fetch game from inside an exercise pen (ex-pen). Safely protected by the portable fence, you can toss balls to your heart’s content without fear of injury, and until your dog is ready to call it quits.

Tug

If your dog prefers tugging to fetching, invest in a variety of sturdy tug toys, and encourage her to tug to her heart’s content, as long as she plays by the rules. If she works her way up the tug toy and redirects her grip to clothes or skin, use a “flirt pole” – a toy attached to a rope at the end of a long, sturdy stick – to keep her teeth safely away from you. If she still redirects to you, stand inside your exercise pen and let her chase the flirt pole toy around the outside of the pen.

Get the Rules for Playing Tug, and see why this game is so good for learning dogs!

Round-Robin Recalls

This group activity is another great exercise option. You and one or more friends or family members stand at opposite corners of the yard and call your dog back and forth to tire her out. If needed, all the human participants can stand safely enclosed in exercise pens. Even standing in a pen, you can trot a few steps to encourage your dog’s high-speed recalls and reinforce with treats or toys when she gets to you.

Play Dates

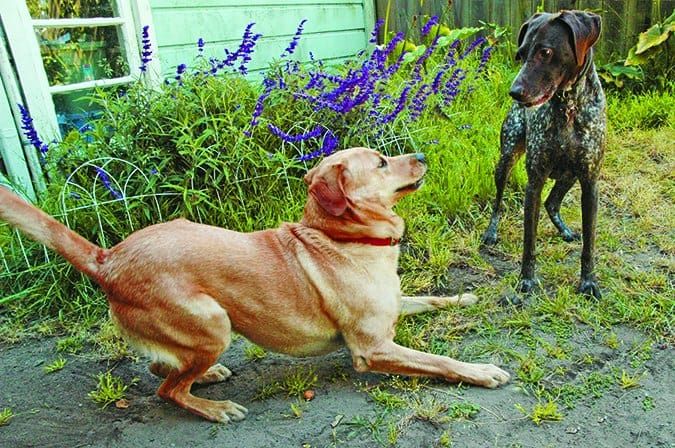

If your dog gets along well with others, arrange for play dates in your fenced backyard with a dog friend several times a week. Appropriate dog-dog play can be an ideal energy diffuser – there’s nothing more satisfying than watching compatible canine pals romping together until both relax on the ground in happy exhaustion.

If you don’t have your own backyard, perhaps you can borrow one. A neighbor, friend, or family member may have a yard that you can use several times a week to give your dog some off-leash playtime. If that yard also comes with a compatible canine playmate, all the better!

Exercise on a Long Line

If you simply can’t find a fenced yard to play in, consider alternatives. You may be able to use a long line (a 20- to 50-foot leash) in an unfenced open space – a beach, or a meadow in a public park that allows dogs and doesn’t have a leash-length limit.

If you do use a long line, take precautions for your dog’s safety:

– Teach your dog a solid recall, so you can call her back if she’s headed for the end of the line at top speed – you don’t want her to hit the end of the line with a full head of steam! (See “Training Your Dog to Execute an Extremely Fast Rocket Recall,” September 2012.)

– Consider using a harness rather than a collar, with your leash attached to a back-clip connection, not front-clip, so if she does hit the end of the line she won’t damage her trachea or twist herself sideways. (See “The 2017 Best Dog Harnesses Review.”)

– Include a bungee-cord connection with the long line, so if she does hit the end there is some give in the line and she won’t hurt herself.

– Manage the line carefully and responsibly so she doesn’t get tangled around trees, brush, or other dogs.

Dog Park

Many communities now offer fenced dog areas to provide off-leash opportunities for canines who don’t have their own fenced yard. There are pros and cons to dog parks, and this may or may not be an appropriate option for your dog.

Dog Daycare

The same is true of doggie daycare. There are some excellent ones out there, and some that aren’t so great. A day at daycare can take a lot of the wind out of your dog’s sails – but check the facility out very carefully before entrusting them with your dog. There are horror stories of daycare facilities using shock collars on dogs without telling the owners.

Ways to Exercise Dogs Indoors

For some of us, safe outdoor play options aren’t available or frequent inclement weather prevails. So, when outdoor exercise isn’t available – or isn’t enough – consider the following:

Stair Fetch

If you have a multi-level home and your stairs are safely carpeted, you are in luck! Stand at the top of the stairs and toss ball or toy to the bottom for her to chase. Again, have multiple balls or toys if necessary. You can put a baby gate across the top of the stairs if needed to protect yourself from jumping and nipping.

Note: If your stairs are not carpeted, consider purchasing and installing adhesive stair treads from your friendly neighborhood hardware store. Caution: If you think your dog will fall down the stairs and hurt herself in her enthusiasm to chase, then this is not a good option for you. No stairs? Toss the ball down a long hallway, or from one room to the next.

Remote Treat Delivery

If your dog is more about treats than fetch, you can try a high-tech option: using a remote-triggered Train & Praise treat dispenser, or the even higher-tech Pet Tutor. Relax on your sofa, watching TV or reading a book, and push a button to trigger the beep that tells your dog that the machine – located at the other end of your home – has just delivered a tasty treat. After your dog runs to get the treats, call her back and do it again. Over and over and over.

Treadmill

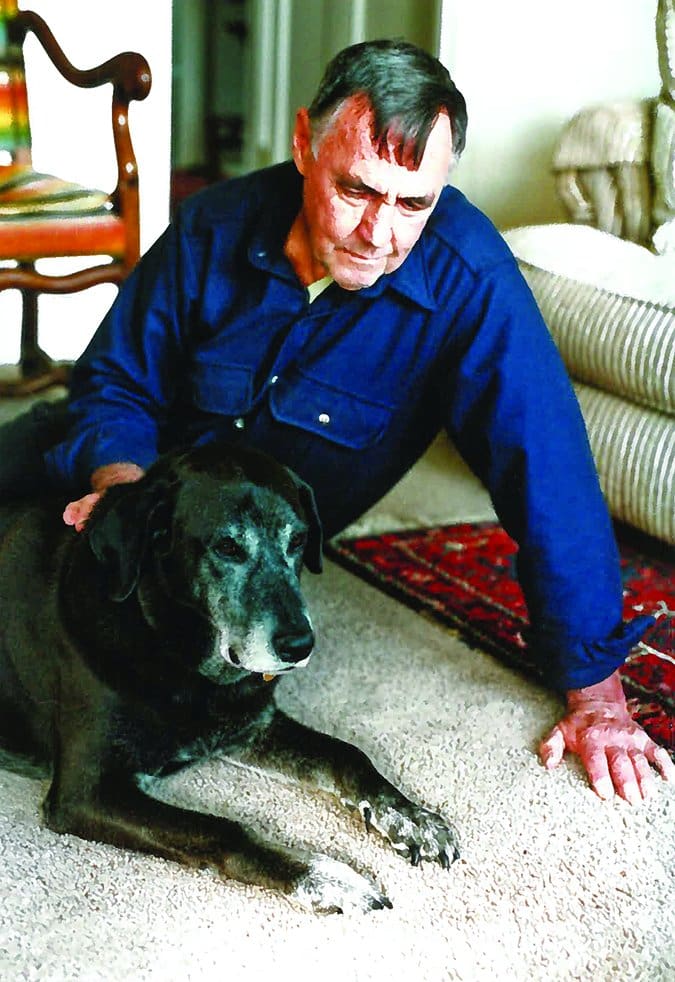

Yes, they make treadmills just for dogs, and yes, some dogs will happily use them – in fact, some dogs practically beg to use them. Not long ago, I went to see a client whose adolescent Labrador, Joker, was mercilessly pestering the two senior Labs in the home, biting and jumping on them. When I sat down on the sofa, Joker immediately began pestering me mercilessly. I ignored his inappropriate behavior, and after a few minutes he went to his human, barked once, and then walked over and stood on his treadmill. My client turned the treadmill on and Joker jogged for 20 minutes, then hopped off and calmly laid down on the living-room floor. I was impressed.

A treadmill is a big-ticket item, but if your dog is extremely hungry for exercise, the investment in a treadmill just might cost less than daycare, dog walkers, and/or private lessons with trainers, not to mention the cost of all the things a bored adolescent dog might chew if he’s not getting enough miles in. (Check out the treadmills made by DogPacer.)

Scent Work

Indoors or out, you can use a dog’s natural affinity for using her nose to your advantage. Most dogs love to use their noses and do it well with minimal training, so it’s pretty easy to implement. In addition, nose exercise is surprisingly tiring. We tend to think that, because they are so good at it, it’s effortless for them, but it actually takes a lot of energy to do all that scent detection. In the wild, where energy conservation is a life-or-death matter, most canids will hunt by sight first, using scent only when absolutely necessary.

Giving your dog a “job” to do with these scent-detection games is a very important and successful strategy for these high-energy, high-arousal dogs.

See “Nose Work is Great Exercise for Dogs!” for an introduction to training this skill.

Mental Exercises to Tire Dogs Out

Mental exercise is very tiring for dogs. Cognitive training games are incredibly effective for using up your dog’s excess energy. Here are a few mind-bending, energy-burning activities that you can use to help settle your wild child:

Imitation games

Claudia Fugazza, an Italian doctoral candidate in the field of ethology (animal behavior), developed a new training method she calls, “Do As I Do,” in which the dog is taught a cue that means, essentially, “Watch me and then do something similar to what I do.” Trainers have been having a lot of fun learning how to employ this new method for teaching new behaviors to dogs and their dog-training students. (For more information, see “Training Your Dog Using Imitation,” October 2013.)

Puzzle Toys

We first reviewed an array of these toys in the June 2008 article, “Interactive Dog Toys.” Dog puzzles offer hidey-holes where you can stash little bits of delicious treats or kibble; the dog has to work out how to open the holes to eat the treats. The puzzles may feature caps that have to be nosed or pawed open or removed, layers that have to be spun, or levers that need to be nudged to one side to reveal the treats. There are many of these puzzle toys on the market now, ranging from very simple to quite complicated; the dog world keeps coming up with new variations on products designed to keep your high-energy dog’s mind well-exercised. Check out toys offered by Nina Ottosson and Outward Hound.

Cognition Games

These are activities that require significantly more mental energy than the simple “If I sit I get a cookie” response. They require your dog to understand and apply concepts such as choice (see “Training Your Dog to Make Choices,” November 2016). Two examples of cognition games are:

– Object, shape, and color discrimination. Teach your dog the names of two different toys, a blue and yellow paper plate, or two different shapes pasted on white squares. Then ask him to touch the correct object, color, or shape with his nose or paw.

– Reading. We’re serious! Dogs can be taught to recognize and remember what some written words look like. See “Teach Your Dog to Read,” October 2006.

Reinforcing Your Dog’s Calm Behavior

Don’t forget the training part of your wild-child rehabilitation program. As much as exercise is vital to help your dog calm down, you also need to manage her environment so she doesn’t have opportunities to get reinforced for over-exuberant behaviors, such as jumping and nipping.

Have her greet new people only while leashed, to prevent her from being reinforced with petting and attention from the people who say, “It’s okay! I love dogs!” You can solicit help from random strangers in public as well as visitors to your home; just restrain your dog and prevent contact if she tries to jump. Instruct those who want to pet her to wait until she sits, or at least has four paws on the floor, and to step back if she jumps up. Meanwhile, make sure you and all your family members are doing the same, even when she isn’t leashed.

If your dog gets aroused and tries to jump on or mouth you when you have her on leash, try threading her leash through a length of PVC pipe. You can use this similar to an animal control pole, to hold her away from you when she get into nippy mode.

A good, force-free training class can work wonders to help and support you in your quest for canine calm. Basic good manners are important for all dogs, and especially for those with more energy than they know what to do with. A well-run group class will help your dog learn how to control her behavior in the presence of other dogs and humans.

To find a trainer, I recommend looking among members of the Pet Professional Guild, trainers who are committed to force-free training; use the directory on the PPG website to find force-free trainers around the world.

Meanwhile, remember to look for opportunities to gently praise your dog when she is being calm. (If your praise is too happy or excited, you risk amping her up again.)

Several trainers have developed calming protocols specifically for working with high-arousal dogs. Dr. Karen Overall, veterinary behaviorist and strong force-free advocate, has created a 15-day thinly sliced “Protocol for Relaxation,” available in her Manual of Clinical Behavioral Medicine for Dogs and Cats, that helps dogs learn impulse control. This detailed procedure begins with your dog sitting calmly for just a few seconds and works up to having her remain calm for minutes at a time while you move around, clap your hands, and even leave the room.

Trainer September Morn, of Olympia, Washington, created “Go Wild and Freeze,” another useful calming protocol. This one starts by having you encourage your dog to get slightly aroused with a “Go wild” cue, and then stand up, hands at chest, as you give the “Freeze” cue. When your dog sits, she gets a click and treat. Gradually increase the level of arousal, until your “Freeze” cue will work to settle her into a sit from any level of arousal.

Happy Endings

I have yet to see a high-arousal nipping, jumping, body-slamming dog who has not been successfully helped by an appropriate combination of exercise and training. In fact, I received an email just today from the owner of the 13-month-old Labrador Retriever I met with two weeks ago. She was thrilled to report that she has already seen significant improvement in her dog’s behavior. I’ll be checking in with the Golden Retriever client soon.