HUMPING PROBLEMS IN DOGS: OVERVIEW

1. Watch for early signs of mounting, and take appropriate steps to discourage them as soon as they arise.

2. Neuter your male dog sooner, rather than later.

3. Use “Good Manners” training and a “Say Please” program (described below) to create structure in your household and give yourself a control advantage.

4. Seek assistance from a positive trainer/behavior consultant if you’re not making progress on your own, or if you don’t feel comfortable addressing the behavior on your own.

Luke had been at the shelter for more than a month, and the staff was delighted when the two-year-old Cattle Dog mix was finally adopted to what seemed like the perfect home. Introductions at the shelter with the adopter’s other dog went reasonably well – although the two didn’t romp together, they seemed perfectly willing to peacefully coexist. Luke went to his new home just before Christmas. Before New Year’s, he was returned.

Her cheeks damp with tears, the adopter explained that the two dogs were fighting. Luke insisted on mounting Shane. Shane would tolerate the rudeness for a while, but when he finally let Luke know that he found the behavior unacceptable, a battle would ensue. The intensity of the fights was increasing, and the adopter was concerned that one or both of the dogs was going to be badly injured. I discussed the situation with her, and agreed that returning Luke was the right decision.

Dog Mounting is NOT About Sex

First, we’re not talking about sexual behavior displayed by intact male and female dogs used for breeding. High hormone levels and normal sexual responses to other intact dogs are different from “problem mounting.” Sometimes, an owner will report that when her young dog plays with other dogs, he gets overstimulated and will attempt to mount another dog or even just “air-hump” for a few seconds. In preadolescent and neutered dogs, this is generally a byproduct of physiologic arousal – an inappropriate response triggered by sensory stimuli, motor activity, and/or emotional reactivity.

The dog who is most likely to be reported as having a real mounting problem is the dog who routinely mounts people, or, like Luke, who mounts other dogs to the point of provocation. This sort of mounting behavior has nothing to do with sexual activity. Rather, it’s often a social behavior, and sometimes a stress reliever. Nonsexual mounting of other dogs is generally a dominance, control, or challenge behavior, although when practiced by puppies it’s primarily about play and social learning, beginning as early as 3-4 weeks. Mounting of humans is strictly nonsexual; it may be about control, it can be attention-seeking, and it can be a stress-reliever.

Dogs will also mount inanimate objects. Our Pomeranian will hump our sofa cushions if we leave the house and take all the other dogs with us. While some dogs do sometimes masturbate for pleasure, in Dusty’s case I’m convinced he’s not seizing a moment of privacy for self-gratification, but rather mounts the cushions as a way to relieve his stress of being left home alone.

In fact, if dogs did wait for some private time to engage in their mounting behaviors, most owners would be far less concerned about it. But dogs, having no shame, are far more likely to take advantage of a visit from the boss or the in-laws to display their leg-hugging prowess. Regardless of how much you love your dog, it’s embarrassing to have him pay such inappropriate attention to your guests.

Get Your Dog to Stop Humping

Like a good many canine behaviors that we humans find annoying, inconvenient, or embarrassing, mounting is a perfectly normal dog behavior. And like other such annoying, inconvenient, and embarrassing behaviors, it’s perfectly reasonable for us to be able to tell our dogs to stop mounting!

Brief bouts that involve mounting of other dogs in canine social interactions might be acceptable, as long as they don’t lead to bloodletting or oppression of the mountee. Mounting of human body parts rarely is, nor is mounting that, as in Luke’s case, leads to dogfights.

So, if there’s a Luke whose mounting behavior is wreaking havoc in your family pack, what do you do?

The longer your dog practices his mounting behavior, the harder it is to change. So it’s logical that the sooner you intervene in your dog’s unacceptable mounting, the better your chances for behavior modification success.

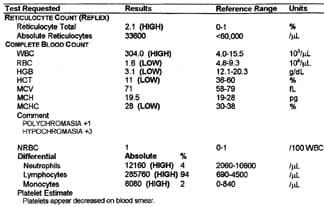

Neutering is an obvious first step. A 1976 study found an 80 percent decrease in mounting behavior following castration. (This is far more often a male dog behavior problem than a female one.) The same study determined that within 72 hours of surgery, the bulk of hormones have left the dog’s system. Since mounting is partially a learned behavior as well as hormone-driven, the extent to which neutering will help will be determined at least in part by how long the dog has been allowed to practice the behavior. Just one more strong argument for juvenile sterilization, between the ages of eight weeks and six months, rather than waiting for your dog to mature.

When Your Dog Humps Other Dogs

Luke, at age two, had been practicing his mounting behavior for many months. In addition, as a mostly Cattle Dog, he was assertive and controlling. When Shane attempted to voice his objections, Luke let him know that he would brook no resistance. Shane, a Shepherd/Husky mix, also had an assertive personality, so rather than backing down in the face of Luke’s assertions of dominance, he fought back. Neither dog was willing to say “Lassie,” and so the battles escalated.

In contrast, we later introduced Shane to a somewhat timid but playful four-month-old Lab puppy. Dunkin also attempted to mount Shane in puppy playfulness. But when Shane snapped at Dunkin, the pup backed off apologetically; in a short time the two were playing together, with only occasional puppy attempts to mount, which were quickly quelled by a dirty look from the older dog. No harm, no foul.

Similarly, you will need to work harder to convince your adult, well-practiced dog to quit mounting other dogs than you will a young pup, and there’s more potential for aggression if the recipient of unwanted attentions objects.

With both young and mature dogs, you can use time-outs to let your dog know that mounting behavior makes all fun stop. A tab (short, 4- to 6-inch piece of leash) or a drag-line (a 4- to 6-foot light nylon cord) attached to your dog’s collar can make enforcement of time-outs faster and more effective when you have to separate dogs – as well as safer.

Set your dog up for a play date with an understanding friend who has an understanding dog. Try to find a safely fenced but neutral play yard, so that home team advantage doesn’t play a role. If a neutral yard isn’t available, the friend’s yard is better than your own, and outdoors is definitely preferable to indoors.

When you turn the dogs out together, watch yours closely. It’s a good idea to have some tools on hand to break up a fight, should one occur.

If there’s no sign of mounting, let them play. Be ready to intervene if you see the beginning signs of mounting behavior in your dog. This usually occurs as play escalates and arousal increases, if it didn’t happen at the get-go.

As a first line of defense, try subtle body-blocking. Every time your dog approaches the other with obvious mounting body postures, step calmly in front of your dog to block him. If you’re skilled, you may be able to simply lean your body forward or thrust out a hip or knee to send him the message that the fun’s about to stop. This is more likely to work with a younger dog, who is likely to be less intense about his intent to mount. Be sure not to intervene if your dog appears to be planning appropriate canine play.

If body blocking doesn’t work, as gently and unobtrusively as possible, grasp your tab or light line, then cheerfully announce, “Time out!” and lead your dog to a quiet corner of the play yard. Sit with him there until you can tell that his arousal level has diminished, and then release him to return to his playmate. If necessary, have your friend restrain her dog at the same time so he doesn’t come pestering yours during the time out.

Keep in mind that the earlier you intervene in the mounting behavior sequence, the more effective the intervention, since your dog has not had time to get fully involved in the behavior. Also, it’s important that you stay calm and cheerful about the modification program. Yelling at or physically correcting your dog increases the stress level in the environment, making a fight more likely, not less.

With enough repetitions, most dogs will give up the mounting, at least for the time being. With an older dog for whom the habit is well ingrained, you may need to repeat your time-outs with each new play session, and you may need to restrict his playmates to those who won’t take offense to his persistently rude behavior. With a pup or juvenile, the behavior should extinguish fairly easily with repeated time outs, especially if he is neutered. Just keep an eye out for “spontaneous recovery,” when a behavior you think has been extinguished returns unexpectedly. Quick re-intervention with body blocks or time-outs should put the mounting to rest again.

Does Your Dog Only Hump Humans?

This embarrassing behavior is handled much the same way as dog-dog mounting. One difference is that you must educate your guests as to how they should respond if your dog attempts his inappropriate behavior.

Another difference is that some dogs will become aggressive if you physically try to remove them from a human leg or other body part. It works best to set up initial training sessions with friends who agree to be human mounting posts for training purposes, rather than relying on “real” guests to respond promptly and appropriately, at least until your dog starts to get the idea.

For your average, run-of-the-mill human mounting, ask your guests to stand up and walk away if your dog attempts to get too cozy. Explain that it is not sexual behavior, but rather attention-seeking, and anything they try to do to talk him out of it will only reinforce the behavior and make it worse. You can also use a light line here, to help extricate your friends from your dog’s embrace, and to give him that oh-so-useful “Time out!” If the behavior is too disruptive, you can tether the dog in the room where you are socializing, so he still gets to be part of the social experience without repeatedly mugging your guests.

If your dog becomes aggressive when thwarted, he should be shut safely away in his crate when company comes. Social hour is not an appropriate time to work on aggressive behavior – it puts your guests at risk, and prevents all of you from being able to relax and enjoy the occasion.

If your dog becomes growly, snappy, or otherwise dangerous when you try to remove him from a human, you are dealing with serious challenge and control behavior. You would be wise to work with a good behavior consultant who can help you stay safe while you modify this behavior. The program remains essentially the same – using time outs to take away the fun every time the behavior happens – but may also involve the use of muzzles, and perhaps pharmaceutical intervention with your veterinarian’s assistance, if necessary.

Do Dogs Masturbate?

Dog owners are often surprised to discover that some dogs masturbate. Our diminutive Dusty discovered early in life that he was just the right height to stand over a raised human foot and engage in a little self-pleasuring if the person’s legs were crossed. We squelched that behavior as soon as we realized what the heck he was doing.

There’s no harm in it, as long as the objects used are reasonably appropriate (say, a washable stuffed animal that’s his alone, as opposed to your favorite sofa cushions), and it doesn’t become obsessive. Removing an inappropriate object or resorting to time outs can redirect the behavior to objects that are more acceptable.

I’ve also known dogs to engage in push-ups on carpeting as a way to enjoy self-stimulation. You can use the time out if your dog chooses to do it in front of your guests, or whenever he does it in the “wrong” room (such as on the living room Berber), and leave him alone when he’s in the “right” room (such as on the indoor-outdoor carpet on the back porch).

If your dog practices the behavior to a degree that appears obsessive – a not uncommon problem in some animals, especially in zoos – then you may need some help with behavior modification.

A behavior is generally considered obsessive when it is causes harm to the animal or interferes with his ability to lead a normal life. If your dog is rubbing himself raw on the Berber carpet, or spends hours each day having fun in the bedroom, that’s obsessive behavior. There are behavior modification programs that can help with canine obsessive/compulsive disorders, and they often require pharmaceutical intervention, especially if the obsession is well-developed.

Other Ways to Modify Humping Behavior

In addition to specific behavior modification programs for mounting behavior, a “Say Please” program can be an important key to your ultimate success. No, we’re not suggesting you allow your dog to do inappropriate mounting if he says “please” first! A Say Please program requires that he perform a deferent behavior, such as “sit,” before he gets any good stuff, like dinner, treats, petting, or going outside. This helps create structure in the pack, and constantly reminds him that you are in charge and in control of all the good stuff. Since a fair amount of mounting has to do with control, Say Please is right on target.

“Good Manners” classes are also of benefit when you are mounting your defense against your mounting dog’s behavior. If he’s trained to respond promptly to cues, the “ask for an incompatible behavior” technique can serve to minimize mounting. If you see your dog approaching a guest with a gleam in his eye, your “Go to your place” cue will divert him to his rug on the opposite side of the room. He can’t “Down” and mount a leg at the same time. Nor can he do push-ups on the rug if he is responding to your request for a “Sit.”

If you start early and are consistent about discouraging your dog’s inappropriate mounting, you should be successful in making the embarrassing behavior go away.

Pat Miller, WDJ’s Training Editor, is a Certified Pet Dog Trainer, and past president of the Board of Directors of the Association of Pet Dog Trainers. She is also the author of, The Power of Positive Dog Training and, Positive Perspectives: Love Your Dog, Train Your Dog.