Download the Full December 2003 Issue

Playing With Your Dog Increases Socialization and Relationships

[Updated February 5, 2019]

When Dusty, our elderly Pomeranian, comes in for his dinner, his tiny feet (slower now than they once were) do a little tap-dance in anticipation of his forthcoming food bowl. I get down on my hands and knees and play patty-paws with the 14-year-old – a game we have shared since he was a youngster. His eyes light up, he tucks his tail and he races gleefully around the room in a mad rush. I smile to see my aging pal’s inner puppy emerge, and reassure myself that there’s a lot of life still left in the furry old guy.

Playing does that. It reminds you – and your dog – of the joys in life; it makes your eyes light up and your tail tuck with glee; it keeps both of you active and young; and it strengthens that all-important bond that is so critical to your lifelong relationship.

Finally, play, and the resulting “feel good” mental response that comes with it, can add an important element of fun to your training program. If training isn’t fun for you and your dog, one or both of you will lose interest, and the end result will be that the program – and the relationship – are both at risk for failure.

Playtime for Dogs 101

Different dogs have different play styles. If I tried to play patty-paws with our Australian Kelpie, she would slink away in horror. Her idea of a rousing good time is to help me bring the horses in for their evening grain. Our Cattle Dog mix, Tucker, would rather fetch a stick or a tennis ball, or go jump in the neighbor’s pond. Our Scottish Terrier’s response to the paws activity would be a bored “Whatever . . . ” but he’d be delighted to engage in a game of “Let’s roust critters out of the drainage pipe!”

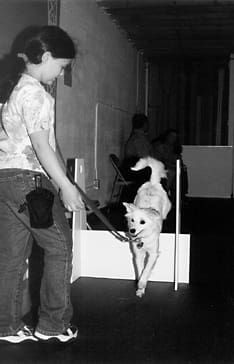

If you want to play with your dog, it’s important to understand his personal play style. Some dogs are happy to engage in a variety of games, others are pretty well fixed on just one or two. Let’s look at several different play styles, the dos and don’ts for each and some tips to help you determine the best way to play with your dog.

People-Oriented Play

These are games for dogs like Dusty, who want to engage with you. The toy, working, herding, and sporting dogs, bred to have close relationships with humans, are high on the list of people-oriented players. Chase, hide-and-seek, and tug of war are great games for people-oriented dogs.

Be sure and establish clear cues and rules for these games; they have the potential to be problematic if you don’t communicate well. You can be a little physical, as long as the dog doesn’t get “mouthy” or use the game as an excuse for body-slamming. Keep your physical contact at a low enough level that it doesn’t elicit aggressive responses. If your dog puts his mouth on your skin or clothing, you should immediately but cheerfully exclaim, “Oops!” or “Too Bad!,” and end the game.

One of Tucker’s favorite people-games is what my husband and I affectionately call “Growly butt scratch.” As the name implies, Tucker gets quite vocal when his rump is scratched, and will even swing his head around and bump his nose on your hand. He never bites, and his growl is a play growl. Nonetheless, this can startle unsuspecting visitors when they innocently reach down to scratch his offered hindquarters! If your dog has any similar games, it’s a good idea to pre-warn visitors.

Note: Some dog owners make the mistake of getting physical with a dog’s head – grabbing the cheeks, pushing and slapping at the face, and encouraging the dog to growl and bite back. This is a very bad idea, because it may encourage the dog to react aggressively when someone reaches for them – a response that could get them in serious trouble if someone misreads their intent even though they are “just” being playfully aggressive. The line between play aggression and real aggression can be fairly blurry, and if the dog crosses over the line to serious aggression, he’s in even deeper trouble.

Object-Oriented Play

These are activities for dogs whose idea of a really good time is to fetch a tennis ball, plush toy, or stick until they keel over from exhaustion. Lots of these dogs will also play with objects with other dogs, teasing a canine pal into a blood-pumping game of “Neener-Neener, I’ve Got the Toy,” which can morph into a canine version of tug of war when the teasee catches up to the teaser.

Some object-oriented dogs will even play by themselves, tossing a toy into the air and chasing or catching it, over and over. I know of at least one industrious Border Collie (and I’m sure there are more) who entertains herself by carrying a tennis ball to the head of a flight of stairs and pushing it off so she can chase it down the stairs and carry it back up, again and again.

Many of the herding, working, and sporting breeds are fond of object-oriented play. Games you can play with these dogs include fetch, find it, tug of war, and put it away. Be careful with this group; they sometimes don’t know when to quit. I had to carry my first Australian Kelpie back to the car on two different occasions – both long hikes – before I realized I had to stop throwing her ball for her when I thought she’d had enough; she would never stop on her own.

Speaking of stop, it’s a good idea to teach your object player an “All done!” cue, or they may bug you mercilessly to keep playing. I do that by saying “All done!,” and putting the ball immediately and firmly away in a closet or drawer.

Task-Oriented Play

These games are for dogs who need to do something meaningful. Terriers are great at this kind of play, as are the herding breeds, many of the working breeds, and some of the hounds. These dogs tend to take their play seriously; once engaged, it can be hard to turn them off.

Terriers can get quite excited about games like “dig it” and “let’s look for a small rodent.” They also excel at complex behavior tricks. The scent hounds, of course, are virtuosos at “find it”; they are limited only by your creativity. Herding dogs top the class at puzzle-solving and anything that resembles herding.

It’s easy to get caught up in the task-oriented dog’s intensity about their “jobs.” When you are using tasks as play, be sure to remember to keep it fun!

You’ve probably noticed that there’s a fair amount of overlap among these groups. Since our goal is to play with our dogs, we want all our games to be “people play,” at least to some degree. “Object play” often spills over into “task play.” In fact, while your dog may have a preferred play style, lots of dogs are perfectly willing to play whatever game you offer. You may have to help your dog develop his play skills in his non-native style, but he may surprise you with his heretofore hidden play talents.

Teaching Playfulness to a Dog

One of the saddest things about a dog who has never had a real relationship with humans is he may not know how to play. Backyard dogs and dogs who are institutionalized from early in life (puppy mill and poorly socialized kennel breeders, dogs who grow up in shelters without adequate stimulation) may not have had the opportunity to learn how to engage playfully with people. Many of them don’t even know how to play with other dogs! In fact, if you try to play with a dog like this you are more likely to scare him. You think you are acting playful and silly, but he just sees you as a human acting weird, and weird equals dangerous.

How do you teach a dog to play? If you’re starting with a new pup, you’re lucky; with puppies, it’s pretty easy. Puppies are born to play! When they do silly, puppy things (non-destructive, non-dangerous behaviors that don’t undermine your good manners training), reward and reinforce them. Instead of always quashing your baby dog’s puppyness, direct it into acceptable outlets and encourage it.

For example, rather than reprimanding your pup for picking up stuff in his mouth, puppy-proof your house, and encourage him to include you when he plays with his toys. If he manages to pick up a forbidden object, invite him to bring it to you, praise him, and trade it for a treat. Bingo! You’ll have a pup who brings things to you. Don’t worry about making him give you the toy; if you get grabby he’ll learn to play keep-away – not a good game! Instead, trade him for a treat, or a toy of equal or greater value.

Starting from early on, show him a toy, hide it in plain view and tell him to “find it!” As he gets the idea, hide the toy in less obvious places. Teach him to find your hiding kids and you’ll have a game the whole family can play, as well as a useful skill in case your kids, heaven forbid, should ever go missing.

When his behavior suggests an undesirable game he’d like to play, figure out how to direct it into a more acceptable activity. Is he digging holes in the backyard? Build him a digging box, bury his toys and bones, and help him dig them up. Eventually you can add a “dig it!” cue and teach him to dig at whatever spot you indicate.

Games for Adolescent Dogs

If you’re starting with an adolescent canine companion, you still have plenty of puppy energy to play with, although you may have to work a little harder to get him to play with you, now that he’s discovered the rest of the world. Start with games that appeal to him.

If he won’t chase things that you throw for him (balls, sticks, etc.), start by tossing yummy, high-value treats, one at a time. Toss one to your right, then one to your left, so he has to come back toward you each time.

When he realizes that delectable yummies are flying from your fingers and is enthusiastically pursuing the tossed goodies, add a cue before you launch, like “Get it!” Remember, you are playing, so any cues you use should be uttered in cheerful, we’re-having-a-wonderful-time play voice. The length of time you play each session will depend on your dog. Always stop while he is eagerly participating, before his interest and enthusiasm flags.

The next step is to stuff a yummy treat in a treat-holding toy, such as a Kong or Goodie Gripper toy, available from most pet supply stores and catalogs. Show your dog the toy with the treat in it, and toss it a very short distance. Let him get the treats out of the holes, then show him another food-stuffed toy, and toss it a short distance, so he leaves the one he has for the fresh one. Remember to keep it fun, with lots of happy praise.

While he is emptying the new toy, retrieve the first one, and stuff it again. When he’s ready, toss it a short distance. Keep swapping, restuffing, and tossing toys. When it’s clear that your dog enjoys this game, add your cue. As he gets good at running after the stuffed toy for short tosses, gradually increase the distance of your tosses. Chances are he will start bringing the first toy at least part of the way back to you, for which, of course, you will tell him he is absolutely brilliant and wonderful.

From there, your dog should be well sold on the fetch game, and can graduate to non-treat toys.

Stodgy Adult Dog Doesn’t Like to Play?

With seemingly non-playful adult dogs, follow the same, gradual steps for teaching play. Look for behaviors that lend themselves to games, and reward and reinforce your dog any time he does them. Encourage puppy-like behavior. Start small, and don’t overwhelm him. If your dog is intimidated by large displays of enthusiasm, keep your reinforcements small but sincere.

For the greatest success, remember to reward your dog with something that he loves. If you do it well, eventually the game will become its own reward. Then you’ll have a wonderful training tool that will allow you to reduce your dependence on food rewards.

For example, if your dog has learned to love playing tug, whip out your tug toy after a great stretch of heeling, and play the game as his reward. If he’s a tennis ball nut, throw his ball as his reward for a super recall, or for a dynamite distance down. Suddenly your entire training program becomes a game!

If you aren’t letting your inner child out to play on a regular basis with your dog’s inner puppy, you’re missing out on one of the greatest joys of sharing your life with a canine companion.

Games You Should NOT Play With Your Dog

A few canine games have high potential for reinforcing undesirable behaviors. While some dogs manage to play these games without apparent ill effect, the risks are great enough that we strongly suggest you avoid them, and thus avoid the risks altogether. After-the-fact behavior modification may be time-intensive and ineffective. Here are a few games we suggest you and your dog pass on:

■ Rough physical games. In addition to the notrecommended face-grab game (described in the text above), some owners like their dogs to get very physical in play, encouraging behavior such as mutual body-slamming and jumping up on humans. The problem is, it’s very difficult for a dog to distinguish between ready-andable play partners and frail and frightened ones.

It’s best to redirect high-contact physical activities to acceptable games such as tug of war (with rules). If you must teach your dog to jump up on you, or into your arms (we’ll admit this trick is cute), be sure to teach her that she can do it only when you give her some obscure verbal cue or hand signal that your grandmother is never likely to accidentally exhibit.

■ Chasing laser lights.It is entertaining to watch a dog chase a laser light beam with frenetic intensity, but BEWARE! The dog who most delights in chasing a laser light is the very dog who is most likely to turn the game into an obsessive/compulsive behavior known as shadow chasing. Shadow-chasers become fixated on any movement of light, and compulsively chase any light, reflections, or shadows that happen to cross their vision.

Obsessive/compulsive behaviors are frightening in their intensity, and difficult to resolve once they occur. Be smart and avoid this game – and any others that elicit intense, compulsive responses.

■ High-energy indoor games. In general, indoor games should consist of activities that require the dog to use his brain, not his brawn. Games that involve mad dashes around furniture, bouncing soccer balls off noses, and burrowing for hidden treasures, are best suited for the great outdoors – not just because they can cause damage to family heirlooms, but also because, in general, encouraging your dog to be calm and self-controlled inside the house is a better idea.

If you live in an apartment with no yard and the only way to exercise your high-energy dog is with indoor play, keep the games very structured. For example, roll a ball down stairs or a hallway, don’t throw it; require your dog to “Wait!” before you release her to pursue the prey; and have her sit and politely drop the ball into your hand when she brings it back. Ask for another “Wait!” before you roll it again. Practice some “moving downs” while she is on her way to the ball, and on her way back.

PLAYING WITH YOUR DOG: OVERVIEW

1. If you don’t already know how your dog likes to play, observe him to figure out how you can best arouse his interest. Select games that are likely to appeal to his natural play style.

2. If your dog has any tendency toward an obsessive/compulsive disorder (OCD), cancel any game that triggers his obsession. For example, chasing a laser light has set many a predisposed dog on the path to OCD.

Pat Miller, WDJ’s Training Editor, is a Certified Pet Dog Trainer, and president of the Board of Directors of the Association of Pet Dog Trainers. She is also the author of The Power of Positive Dog Training and Positive Perspectives: Love Your Dog, Train Your Dog.

Safe Canine Weight Loss Tips

by C.C. Holland

Does your dog waddle when he walks? When he lies around the house, does he cover more floor space than your area rug? Does he have four legs – and two chins?

If so, you may have an obese dog. But despite the inclination to view fat dogs as happy or jolly, it’s no laughing matter.

Recent studies indicate that up to 40 percent of dogs in the United States may be obese. The risks associated with canine obesity include musculoskeletal disorders such as osteoarthritis, compromised immune function, problems during surgical procedures, delayed wound healing, skin infections, and diabetes.

For these reasons, it’s a good idea to get Fido back into shape. Improved health, quality of life, and longevity are some of the benefits of keeping your canine companion trim. Last year, the Purina Pet Institute completed a 14-year study that found that dogs who consumed 25 percent fewer calories than their litter-mates during their lifetimes maintained a lean or “ideal” body condition and lived longer – nearly two years longer, on average.

First: Is your dog fat?

Charts and tables might give you a general idea of your dog’s recommended weight range, but due to the variations found between male and female dogs and even within breeds, it’s not an exact science. If you have a mixed-breed dog, weight charts may be of no help.

Instead, most veterinarians and nutritionists advocate using a hands-on approach to assessing body condition (see sidebar). A healthy dog will have a waist when viewed from above, have a tucked stomach when viewed from the side, and will have ribs that are easily felt through a very thin layer of flesh. If any of these hallmarks are absent, your dog may be slightly overweight. If all are missing, and if you notice fleshy deposits over the chest, spine, and base of the tail, your dog is obese.

Causes of obesity

As with humans, there are many factors that cause or contribute to weight gain. A variety of medical conditions can predispose your pet to excess weight. For example, hip dysplasia, osteoarthritis, or ligament injuries can limit your dog’s activity and contribute to weight gain. Metabolic diseases such as diabetes or hypothyroidism can also cause obesity. The first step in treating any overweight dog should be a trip to the veterinarian, to rule out these possible disease-related causes.

Some breeds are predisposed to pack on the pounds. Among these are Labrador Retrievers, Beagles, Basset Hounds, Dachshunds, Cocker Spaniels, Cairn Terriers, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, and Shetland Sheepdogs. If you own one of these dogs, you will probably need to be more vigilant than the average owner to make sure your dog doesn’t put on extra weight.

In addition, when an animal is spayed or neutered, its energy needs decrease by about 25 percent, according to information provided by Ohio State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine. Many people believe that altered pets “automatically” become overweight. The truth is, the dog’s food ration should be decreased following neuter or spay surgery, as his or her body adjusts to lower hormone levels.

Age can also add weight. As body metabolism slows and older dogs are less active, lean body mass can decline and extra fat can creep in.

But by far the biggest reason dogs get fat is the same that humans do: they simply take in more calories than they burn. And for that, you can blame yourself.

“We are facing an epidemic of canine obesity,” said Dr. Nancy Peters, a veterinarian in private practice in Apex, North Carolina, who participated in a recent weight-management study by Purina Pet Products and North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine. “And it is largely due to consistent owner behaviors, not the dog’s. We mean well, but we may not be doing what’s best for our pets.”

Feeding over-large portions and not providing enough exercise are the biggest culprits. But dogs who “scrounge” for extra food – the cat’s food, cat poop, dead things in the yard, stuff from the garbage, or compost heaps – can maintain bulk even when their “official” rations keep decreasing.

Also, dogs are quick to learn behaviors that reward them with tasty treats – and we’re not talking about the types of behaviors that the person tries to teach the dog; we’re talking about the behaviors the dog learns to “trick” the person into feeding him. Many people seem unable to resist large, pleading eyes watching them eat, and slip the dog morsels from their plates. Some dogs learn to pose and beg in front of the dog-cookie jar, causing their owners to say, “Aw! So cute!” and hand over a biscuit.

But while the equation of too many calories + too little exercise = overweight dogs seems simple, it can be anything but. Tony Buffington, DVM, dipl. ACVN, is a professor of clinical sciences at Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, where he and his colleagues have developed an obesity therapy program for cats and dogs. He says weight management sounds like an easy issue, but plenty of other factors complicate things. For one: stress.

“There’s some evidence to support the link between stress and eating,” he says, drawing a parallel to how some humans respond to stress by chowing down. Also, a sense of power plays a part: “I think that animals’ perceptions of control of their environment also modulate their energy balance. We don’t have any idea to what extent we manipulate those perceptions and how that affects weight loss.”

In some cases, owners get some psychological benefits from poor feeding habits. For example, the owner who constantly spoils her dog with treats may enjoy a sense of bonding and closeness with her pet that she fears would be lost with a stricter feeding regimen.

On the other side of the coin, owner inattention can also result in a portly pooch. The owner who doesn’t have the time or the inclination to measure food might simply dump it into a bowl and refill it whenever it’s empty. If the same owner doesn’t pay much attention to exercise or interacting with the dog, the pet may simply eat too much out of boredom.

Trimming the fat

The good news: The dangers posed by obesity can be removed simply by shedding a few of your pup’s pounds.

“In most cases, a 20 percent weight loss will take even grossly obese animals out of the high-risk category for obesity-related diseases,” says Dr. Buffington.

To start your dog back on the road to slimness, start by aiming for a 10 percent weight loss – or a rate of about 1 percent of his body weight per week. A slow approach is recommended both because it allows for a more gradual change in feeding, and because studies show that rapid weight loss can increase a loss of lean body mass, which in turn can contribute to weight regain. (Lean body mass, which includes organs, are the primary drivers of basal metabolism and burn energy at far higher levels than fat mass does. Reducing the amount of lean tissue can create diminished energy requirements, so a dog can regain weight even if he’s eating less.) In other words, forget the idea of crash diets for your dog; slow and steady wins this race.

The first step: weigh your dog. Next, calculate how much your dog actually eats. Begin by listing all the food your dog gets every day, including treats and table scraps, and add up the total calorie count. Some commercial foods carry calorie information on the label; for others, you may need to take the initiative and contact the manufacturer for more details.

Make sure you take portion size into account. If the recommended ration of your kibble is two standard cups a day, but if you’re using a 16-ounce Big Gulp container to measure out the food, you’re actually feeding your dog twice the allowance – and twice the calories.

To calculate calories in non-packaged foods, such as peanut butter, table scraps, and so forth, Dr. Buffington recommends visiting the USDA’s National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference (see www.nal.usda.gov/fnic/foodcomp/Data/SR16/sr16.html), or using one of the various food-value books on the market today. An excellent reference is Bowes and Church’s Food Values of Portions Commonly Used, by Jean Pennington, et al. (At $50, this is a costly book, but useful for researching dietary concerns for your whole family. A paperback version is due out in early 2004.)

Once you have arrived at the total calories ingested by your dog, it’s time to calculate how much weight your dog should be losing – and how many calories to subtract from his diet. Again, if your dog is overweight, you should aim for a 10 percent weight loss overall, at a rate of about 1 percent per week.

If you’re inclined to pull out your calculators, here’s how the math works: If you have a 100-pound dog, a 1-percent weight loss would be 1 pound per week. One pound is equal to 3,500 calories. Thus, you’ll need to reduce his food intake by 3,500 calories per week, or about 500 calories per day.

For a 50-pound dog, the goal is to lose ½ pound per week, which means trimming weekly 1,750 calories (or 250 calories per day).

Or, there’s an easier method. Dr. Buffington uses a general rule of thumb: “Multiply your dog’s current weight by 5, and subtract that number from its current (daily) calorie intake.” In the example above, then, the 100-pound dog should have 5 x 100 calories, or 500, subtracted from his daily diet – the same figure you arrive at by doing the complicated math.

Make dietary changes

You can begin feeding at the new levels either by reducing the total amount of food you give your dog or by changing his diet. For example, you can replace high-calorie snacks with lighter fare (such as carrots, apple slices, or broccoli); reduce or eliminate table scraps; feed mini-meals throughout the day rather than two main meals (this can help reduce begging); or switch to a lower-calorie food formulated for weight loss.

Switching your dog to diet food is not a requirement, says Dr. Buffington: “Most people could feed less of the same food and they’d be fine,” he says. But he warns that cutting back too far can lead to problems. “In some animals, you’ll get to the point with the amount you’re feeding so little that they actually become at risk for nutrient depletion, especially in older or sedentary animals. So cutting back too much can be risky,” he says.

If you’re concerned about this, talk to your veterinarian. In cases like these, Dr. Buffington says, owners might be told to feed a puppy formulation, which is more nutrient-dense. And if you prepare your dog’s meals yourself, Dr. Buffington strongly encourages consulting a nutritionist and including a vitamin/mineral supplement.

If you do decide to try a commercial, low-calorie canine diet, you’ll notice that some tout their low-fat formulations; others trumpet high-protein, high-fat, low-carbohydrate combinations. Dr. Buffington says the last thing you need to worry about is whether your pet should be on the South Beach diet or the Atkins plan.

“It’s completely irrelevant to the health aspects of obesity therapy,” he says. “The relative percentages of carbohydrates to fats to proteins in diet are pretty meaningless.”

Pay attention to how much weight your dog is losing. If the weight loss is greater than two percent in a week, you may be cutting back too drastically; if it’s less than one percent, you may need to trim back further. Slow is the name of the game – remember, your pet didn’t add all the weight overnight, so don’t look for a quick fix.

Add in exercise

Exercise can be an important adjunct to nutrition in promoting weight loss. Which one plays a more important role in the slim-down program depends in part on the owner, says Dr. Buffington.

“The most important thing is what the client wants to do the most, because that’s what they’re most likely to do,” he says. “If you want your dog to lose weight, the animal needs to have a negative calorie balance of 5 calories per pound of body weight per day. You can either take 5 calories out of his bowl, exercise 5 calories out of him, or any combination of the two.”

If your dog was only slightly overweight to begin with, you can increase your dog’s exercise from the get-go. Add in a short walk each day. If he’s young and not prone to joint problems, increase the intensity of his exercise as he loses weight, by playing fetch in a hilly area. Feed your dog part of his rations in Kongs or other stuffable toys, so he has to expend energy while eating.

If your dog is quite obese, exercise should be introduced gradually. Too much activity can be dangerous to a very fat dog. Ohio State’s obesity-therapy guidelines suggest setting a goal to increase the pet’s activity by 1 minute a day until a goal of 10 minutes a day is reached. Once that level is attained, the duration can again be slowly increased.

Work for the long-term

The goal in an obesity therapy program is not primarily to lose weight; it’s to keep weight off. That means you’ll need to keep an eye on your dog’s waistline for the rest of his life. (Ideally, weigh your dog at least once a month, rather than waiting to notice physical signs that the dog has gotten fat.)

As your dog ages and his metabolism slows, he may require fewer calories to maintain his weight. If you notice weight gain, adjust his food accordingly, and if you’re concerned about him not getting adequate nutritional support, see your veterinarian. On the flip side, if he’s losing weight, that could signal an underlying illness. Consult your veterinarian before you increase his rations.

And don’t forget daily walks and games of fetch as part of his weight-management routine. Your aging dog may not appear as interested in exercise – but don’t let that keep you from giving it to him.

“Older animals are less spontaneously active, but they’ll participate if they’re invited to be active,” says Dr. Buffington. “Young dogs will often come to you with their leashes in their mouths. Older dog won’t necessarily do that. But if you bring the leash to an older dog, he’ll undoubtedly get up and head out the door.”

Reality check

Finally, suggests Dr. Buffington, if you think your dog is carrying a bit of an extra load, don’t panic and put him on a starvation diet.

“I’m not promoting overweight, but the truth is, the health risks of obesity in dogs and cats are lower than those in people,” says Dr. Buffington. He worries about people who get “overscientific and underemotional” about slimming their dogs. After all, food and bonding often go hand-in-hand, he says. “I would rather see an owner with a really happy dog who’s slightly overweight than one who destroys her relationship with the dog to give it six more months of life.”

-C.C. Holland, a frequent contributor to WDJ, is a freelance writer from Oakland, California.

Download the Full November 2003 Issue

Join Whole Dog Journal

Already a member?

Click Here to Sign In | Forgot your password? | Activate Web AccessOld Dog

I havent talked about my senior dog, Rupert, for a while. Hes living with my dad out in the country, but I get to see him about once a month. Hes completely happy living with my dad, and far more comfortable there than at my house.

Rupe likes to follow his favorite people like a shadow, which has gotten somewhat problematic in his creaky old age. Our last visit to the Veterinary Medical Teaching Hospital at the University of California at Davis pinpointed the source of Ruperts declining mobility as his knees, whose ligaments were frankly described as blown out. At 14 years old, with cardiac arrhythmia, high blood pressure, and failing kidneys, hes not a candidate for surgery. As my dad says, Once he gets up, he gets around. Just like me!

When I first sent Rupe to stay with my dad, I saw it as a temporary deal. My mom had just passed away, and I knew my dad would benefit from Ruperts constant offer of love and attention. But Rupe has benefitted from the arrangement as well.

At my house, my office is down a flight of stairs, and Im up and down the stairs all day. This left poor Rupie either standing and staring, disconsolate, at my office door (hes also pretty deaf, and his vision is not all that great, either), staggering up the stairs, or coming down them in a more or less controlled fall.

My dads house doesnt have even a single step. Plus, my dad is retired, which gives him lots of time to pet a deserving dog. Plus, when Rupe goes outside, there are sticks absolutely everywhere not a surprise, as my dad lives in the woods, but it makes Rupies heart sing to find crunchable toys everywhere he turns.

Rupert is happy to see me when I show up at my dads house for a visit, and he whimpers excitedly as he greets me, tail wagging and eyes shining. But I notice that he doesnt follow me every time I go outside; he only makes the effort to get up and go out when Dad goes out. And at bedtime, he sleeps at the foot of my dads bed, not on my sleeping bag with me on the floor of the living room, like he used to when we would visit.

On the other hand, Dad says that Rupe would absolutely not allow him to undertake all the grooming that I perform on the furry old dog every time Im there. I give Rupe a bath, pick the foxtails out from between his toes, clean his ears, cut his nails, and check the current size and location of all his fatty tumors. He looks like a star when Im done, and smells and feels so good I cant help but kiss his shining head again and again.

I dont know if Rupert will make it through one more winter; well see. For now, hes in the best possible place, and even though I miss him, Im happy hes happy.

-Nancy Kerns

How to Best Utilize Your Dog’s Next Blood Test

by Randy Kidd, DVM, PHD I have always thought it almost magical that with only a few drops of blood, I can get a fairly comprehensive picture of what is going on with a dog’s inner chemistry. Most of the dog’s organ systems can be targeted by one chemical analysis or another, and with proper interpretation of one (or a combination of) these analyses, I can, at least in part, assess the dog’s current health/disease status. From this interpretation then, we can often derive a treatment regime, whether it is based on Western or alternative medicines. Isn’t science wonderful? However, over the years I’ve learned that interpreting blood chemistry results and then deciding on a therapeutic protocol based on the interpretations is often more art form than strictly black and white science. And while it can be frustrating when we are not able to generate specific answers from the blood chemistry findings alone, I personally find it comforting that there is still some magic and mystery in this specific area of science. As a holistic vet I’ve learned that there are many other very valid methods that can be used to interpret the patient’s health/disease status – evaluating the Qi of Traditional Chinese Medicine, or employing the intake of symptoms used in homeopathy, as just two examples. I’ve found these alternative diagnostic methods, depending on the situation, to be as good as, or better than, the “scientific” blood analysis methods employed by Western practitioners. To my way of thinking, we offer our patients the best of all worlds whenever we have the ability to accurately interpret several different methods of diagnosis (see “Personal Notes About Blood Chemistries,” at end of text). Whenever we decide to use blood chemistries as an aid for diagnosis and treatment, we need to understand what the results are telling us – and what, by design, they cannot help us with. Following are some of the basics of blood chemistry analyses. Bear in mind as you read that blood chemistries are a snapshot of what is going on inside the dog. They do not provide us a story with a beginning, middle, and end, and it is often this whole story that is the most valuable for determining our treatment protocol. To really know how a disease is progressing, we will perhaps need several progressive “snapshots,” each one giving us a better insight into the whole story of the dog’s ongoing health status. Also, remember that all blood chemistry interpretations rely on the methodology of statistical analyses, one of the mainstays of the science of Western medicine. While I appreciate that decisions based on statistical concepts can usually be justified, I always need to remind myself that each and every patient is a “statistic” of one – an individual who may or may not conform to the rules the statisticians ask us to abide by (see sidebar). Finally, keep in mind that dealing with a concept that interprets “normal” as a value that falls within the parameters of what is statistically normal in a given population. This “normal” value is completely disconnected from the holistic totality of the animal patient, and individual variability often throws a monkey wrench into the whole system. Statistics are entirely blind, and it is up to the people interpreting them to actually observe the animal to see if the statistics correlate to the symptoms seen in the dog. Woven into the concept of “statistically normal” is the fact that fully 5 percent of every perfectly healthy population will lie outside the normal range. Further, when we run a blood chemistry profile on a healthy animal using the typical 20 or so separate analyses, we almost guarantee that at least one of the values will fall outside the normal range. (Statistics can be used to prove this, but I won’t burden you with the mathematics here.) Unfortunately, even though we should expect a perfectly healthy animal to have at least one value of his chemistry profile that is outside the range of normal, I find that far too few veterinarians really understand this concept, and they will often base entire treatment protocols on the one “falsely abnormal” value they have obtained from a chemistry profile. We should instead be looking for “concordant” values – two or more values that support each other in their evaluation of a particular organ system. For example, when we have several indicators of liver disease (for example: elevated alanine transferase, aspartate transferase, and alkaline phosphatase, and decreased total protein and albumin), we can be reasonably sure the liver is involved. However, if only aspartate transferase is elevated, we need to think of other possibilities – in this case the likelihood that there is muscle rather than liver damage. The key, then, is to work with values that represent concordant indications, and to scratch your head and wonder about (or ignore) the ones that are discordant with other values. Finally, when “abnormal” values don’t match up with the aggregate of all of the dog’s physical symptoms, they should be questioned. Definitive answers not likely It is actually rather rare when blood chemistries, even with the most complete profile possible, will give us a definitive answer to the question, “Specifically, what is wrong with this dog?” When we use blood chemistries to help diagnose disease, we hope: a) We’ll be able to eliminate some of the possibilities from the long list of potential causes of disease; b) We’ll come closer, often through the process of elimination, to the real cause of the disease; and c) We can pinpoint one (or more) organ system that needs therapeutic support, thus giving us some help in developing our treatment protocol. While it can be frustrating to run a blood chemistry profile on a sick animal and not come up with the precise cause of the disease, I’ve found that “healthy animal” profiles can be very useful. Using a profile, we may be able to detect a beginning trend toward a potential problem, and this gives us a chance to design a long-range, holistic protocol that will help the dog maintain optimum health. My caveat here is that we make certain we are dealing with an actual trend and not just a few select values that are really within normal range but are slightly one side or the other of the median value. All labs are not all equal Quality control, accuracy of results, turnaround time, cost, and the chemical methodology used to establish “normal” values are all factors that enter into the reliability of the results you obtain from any lab. Veterinarians often use a local human lab to save costs and time, but very few of these labs have established their own normal values using healthy animals instead of humans, and they often are able to ease their quality control measures for the animal samples they run. And, while many vets use in-house blood chemistry instruments, it is almost impossibly expensive to run adequate controls to insure quality results. Ask your veterinarian about the laboratory he or she uses. For the reasons I just outlined, I strongly recommend using only university-based or large commercial veterinary laboratories. Inaccuracies and interactions Probably more important than “lab error” as a cause of spurious or incorrect values are interactions with other substances. Many of these interactions are caused by problems within the blood itself. For example, hemolysis (breakdown) of the RBCs can result from problems during collection, and lipemia (fat in the bloodstream) can be caused by taking the sample too soon after a meal. However, a good many of the interactions are caused by a variety of drugs the animal may be taking at the time of the test. Your veterinarian should be advised about any and every drug or herb your dog is being given, and he or she will need to know how each affects the blood chemistry results. There are many other considerations that make analysis of blood chemistries a true art form. For example, you always need to think of the various ways a chemistry can be increased – such as increased production, spillage from the rupture of cells, or lack of proper clearance or excretion – and then you need to decide which of these mechanisms is occurring in this particular patient. Finally, the veterinarian also needs to consider such individual variables as the age, sex, breed, activity level, and pregnancy status of the animal, as each of these may affect normal ranges. Here is a question I frequently get from clients and veterinarians: “What other tests should I run?” The answer is simple: What will you do with the results? If a positive (or negative) result will change your treatment regime, then the test may be warranted. If you will continue on with the treatment protocol you’ve already begun, why bother with more tests and expense? You’ll likely only confuse yourself further anyway. Common blood test results The following are a few of the more commonly run blood chemistries and some of the things to watch for when reading their values. The list is not complete and is only meant to help with more routine cases; check with your vet or a veterinary specialist (clinical pathologist or internist) for further information. Alkaline phosphatase (ALP): ALP is an enzyme found in a variety of tissues; the two tissues of diagnostic importance are bone and liver. Two common causes of increased ALP are the use of glucocorticoids (any of the many cortisone-type drugs) or anticonvulsant medications (such as Phenobarbital and primidone). Bone and liver ALP have separate isoenzymes that can be identified by special analysis (electrophoresis), but with the exception of bone disease or bone growth (growing animals or during fracture repair), increased serum activity that is non-drug-induced is usually due to liver disease. Alanine transferase (ALT): Increased values are principally due to damage of liver cells from any cause. (Red blood cells and muscle cell damage may also cause small increases.) Liver disease of any type may elevate ALT values; the list of drugs that are known to damage liver cells is extensive; further, an animal may have an idiosyncratic reaction to almost any drug or nutritional supplement. Aspartate transferase (AST): AST is found in many tissues including liver, muscle, and blood cells. The most common causes of increased AST include liver disease, muscular disease (inflammation or necrosis), or hemolysis (the breakup of red blood cells). While increased AST is often associated with liver cell damage, it is not as specific for liver as is ALT. Exercise and intramuscular injection may also increase serum AST. Finally, ALT is present in the cytosol of the cell, while AST is found in the mitochondria. Because cell membranes are more easily damaged than mitochondria (allowing for leakage of the enzyme from the cytosol), it is easier to increase serum ALT than AST. Kidney tests: Complete renal exams include BUN, creatinine, and a urinalysis. BUN is a prime example of a test where interpretation can be thought-provoking. BUN can be moderately elevated by any factor that increases body protein – possible examples include: a recent canned meat meal, hemorrhage into the gastrointestinal tract, breakdown of body tissues from fever or massive tissue trauma, or drug therapy including corticosteroids or tetracyclines. If both creatinine and BUN are increased, the kidneys are affected (decreased glomerlular filtration). However, decreased glomerlular filtration may be due to prerenal causes (diminished blood supply due to dehydration or shock); postrenal causes (diminished outflow from a “plugged” urethra); or renal causes (including a variety of true renal diseases). In early prerenal conditions, the BUN may be elevated before creatinine values, due to the highly diffusible nature of BUN. Prerenal conditions will typically be associated with urine specific gravities of greater than 1.035; a persistent specific gravity of 1.010 + 2 indicates the kidneys are unable to function. It’s important to have pretreatment values since many treatments alter one or all of the BUN, creatinine, and urine specific gravity values – fluid therapy, corticosteroids, and diuretics are just a few examples. Decreased BUN may also indicate disease and may be caused by inhibiting production (e.g., liver insufficiency or dietary protein restriction) or by increasing excretion (e.g., excessive thirst and urination or late pregnancy). Pancreatic tests (amylase and lipase): These two tests should be done simultaneously to diagnose pancreatitis. Amylase levels may rise with renal disease (and other diseases are suspected, but not proven), although the elevation is usually less than two times the upper limit of normal. However, pancreatic disease, no matter the severity, does not produce a reliable increase in amylase values. Adding lipase increases the likelihood for an accurate diagnosis of pancreatic disease, but lipase values may also elevate with renal disease (and some drugs), and not all patients with pancreatic disease will have elevated lipase values. The amount of increase of either the lipase or amylase values is not necessarily proportional to the severity of the pancreatitis, and each of these two values will have very different normal ranges between labs, depending on the lab’s methods of analysis. Cholesterol: Used as a screening test for hypothyroidism, hyperadrenocorticism (“Cushings syndrome”), diabetes, kidney disease, and other rare diseases. Feeding a very high fat diet may cause minor elevations of cholesterol in the dog. Cholesterol levels may be high immediately after eating, and there are several drugs that may falsely elevate cholesterol values. When high cholesterol values are found, other tests will be needed to help determine the cause. Glucose: A general screening test that, when out of normal range, will often require follow-up tests to further narrow down the real cause of the abnormality. There are many possibilities for lowered values, including insulin therapy, being a toy breed puppy, tumors, and prolonged starvation, but probably the most common cause is that the serum was not separated from the red blood cells. (Red blood cells continue to metabolize glucose, even out of the body, and their metabolism eats up glucose.) There are also many causes of increased glucose, although a persistent value of more than 180-200 mg/dl in a non-stressed animal not receiving medication (especially glucocorticoids) is indicative of diabetes mellitus. Note that glucose is a good example of a “snapshot” blood chemistry, good for monitoring the short-term results of therapies for diabetes. However, other chemistries (fructosamine or glycosylated hemoglobin) provide a better way to see how the therapies are progressing over a few weeks or months time. Electrolytes [sodium (Na), chloride (Cl), potassium (K)]: Electrolytes are an important component of the blood serum. In addition to providing necessary minerals for many chemical reactions, electrolytes balance the “thickness” (osmolality) of the serum as well as helping to maintain a constant acid/base balance. Depletion or excess of any of the electrolytes prevents the kidney from functioning properly, makes cellular uptake of nutrients difficult, and may alter the acid/base balance enough to be life-threatening. Physical causes that may create an imbalance include vomiting, diarrhea, inadequate kidney function, and/or improper fluid intake. Again, there are many drugs that can cause imbalances. If the sodium value is less than 135 mEq/L or if the ratio of Na:K is equal to or less than 27:1, and if we can eliminate sampling errors and other artifacts, hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s), a potentially life-threatening disease, should be suspected. Calcium and phosphorous: Two additional electrolytes with additional importance for healthy bones and proper nerve transmission. Increased levels of calcium may be caused by many factors including endocrine disease (of the parathyroid, thyroid, or adrenal gland), renal disease, infection, inactivity, dehydration, or excess intake of vitamins A or D. Calcium is also elevated with the presence of several types of tumors, whether or not they involve bone tissue. There are many reasons for low blood calcium levels – including kidney disease, endocrine imbalance, toxicity (especially to ethylene glycol found in some antifreeze products), and thyroid surgery. But, the most common cause is a low level of the blood protein, albumin – from lack of nutrition or liver disease. Animals with very low blood calcium levels may have heart arrhythmia (from lack of proper nerve transmission), or they may go into rigid spasms (eclampsia of pregnancy, is an example of this). Although there are many causes of elevated phosphorous, the most common is kidney disease, and values can be profoundly elevated with this condition. Low levels of phosphorous are commonly, but not exclusively, associated with increased calcium seen along with malignant tumors. Serum proteins (Total proteins, albumin (the most prevalent serum protein), and globulin): Serum proteins evaluation is used as a general screening test for most patients but especially for those with edema, blood clotting problems, diarrhea, weight loss, and hepatic or renal disease. This is to say that either elevated or decreased levels point the diagnostician in the direction of trying to find the reason for the abnormal value. Elevated total proteins, for example, may be caused by many factors, but the most common one is dehydration. Albumin may be low due to lack of intake (nutrition or absorption), lack of production (liver disease), or increased loss (from the gut or kidney). Increased globulins may indicate chronic infection or immunological disease. In some cases deciding which of the globulins are increased (whether it’s the alpha-, beta-, or gamma-globulins, each of which also have several separate fractions) can be beneficial for diagnosis; the various fractions can be separated via electrophoresis. Thyroid profile: Most chemistry panels nowadays include a T-4 evaluation, a basic screening test for thyroid function. However, even as a screening test, it is generally felt to be unreliable because it can over-diagnose hypothyroidism (the most common thyroid disease in dogs), under-diagnose hyperthyroidism (the most common form in cats); may fail to detect early stages of the disease; and it doesn’t identify immune-mediated forms of thyroid disease. Further, the test is influenced by other diseases that may produce spuriously low values, and many drug therapies influence results. For a more complete diagnosis several tests are available, depending on the patient’s symptoms. These include free (unbound) T-4, free and total T-3, endogenous canine thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH), canine thyroglobin autoantibodies (TgAA), and T-3 and/or T-4 autoantibodies. Summary I’ve found both blood chemistry values and alternative methods of diagnosing to be valuable aids in my overall diagnostic process. Sometimes one method gives me a better idea for diagnosis and treatment; other times another method provides much better information. Since I’ve not been able to figure out in advance when a particular method will be the one that will work for the individual patient, I’m glad I have several very different methods to work with. I often find that working with a combination of many diagnostic methods gives me and my patient the best of many worlds. -Dr. Randy Kidd received a DVM degree from Ohio State University and a Ph.D. in Pathology/Clinical Pathology from Kansas State University. He is a past president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, and author of Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Dog Care and Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Cat Care.

Dog Cancer Diet

DOG CANCER DIET: OVERVIEW OF WHAT TO FEED YOUR DOG

1. Reduce the carbohydrates your dog eats. Carbs cause a net energy loss to the cancer patient, but are readily utilized by cancer cells.

2. Use fish oil supplements (high in omega3 fatty acids ) to reduce or eliminate some of cancer’s metabolic alterations.

3. Feed the most appetizing food you can find. Anorexia and weight loss will speed your dog’s death.

Ask any dog owner about his biggest health fears for his pet, and his response is likely to include cancer. It’s a leading cause of death in canines and can be indiscriminate, striking young and old dogs alike. According to a 1997 Morris Animal Foundation study, cancer claimed the lives of one of four dogs who participated in the study, while 45 percent of dogs who lived to be 10 or older died of cancer.

Many cancers are life-threatening. Although they can be addressed through conventional veterinary treatments, including surgical removal of tumors, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, they may not always be cured, so post-diagnosis regimens often focus on simply creating the best possible quality of life for the time the dog has left.

Over the past 10 years, compelling evidence has emerged that one of the keys to creating that better life can be found in a surprising place: the dog’s food bowl. Experts acknowledge that one way to deal with cancer is to take charge of what the canine cancer patient eats.

How Cancer Alters the Metabolism of Dogs

Veterinarians studying canine cancer have long known that the disease alters a dog’s metabolism. The cancer-stricken dog will utilize carbohydrates, fats, and proteins in very different ways than his healthy counterparts.

In many cases, canine cancer patients will also exhibit what’s known as cancer cachexia, a condition in which an animal will lose weight despite taking in adequate nutrients. (Cancer cachexia occurs in up to 87 percent of hospitalized human cancer patients, and because the incidence of malignant disease is higher in dogs than in humans, there is reason to believe that cancer cachexia is at least as significant a problem in veterinary patients.) Dogs with cancer cachexia show a decreased ability to respond to treatment and a shortened survival time.

Greg Ogilvie, DVM, Dip. ACVIM, and his colleagues at Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences are regarded as the top experts on canine cancer in the United States. In 1995, Ogilvie coauthored a landmark textbook, Managing the Veterinary Cancer Patient, that further describes the metabolic changes that occur when a dog contracts cancer.

According to the text, the most dramatic metabolic disturbance occurs in carbohydrate metabolism. Cancer cells metabolize glucose from carbohydrates through a process called anaerobic glycolysis, which forms lactate as a byproduct. The dog’s body must then expend energy to convert that lactate into a usable form. The end result? The tumor gains energy from carbohydrates, while the dog suffers a dramatic energy loss.

In a dog whose cancer is yet undiagnosed, this can be disastrous. What is the average dog owner’s first response when his dog starts losing weight? He generally increases the dog’s food ration – and if that food is a conventional kibble containing lots of carbohydrate-heavy cereal grains, he ends up throwing gas on the flames, so to speak. The dog does not benefit from the increase in carbohydrate-laden food, but his cancer does.

Another metabolic alteration seen in dogs with cancer cachexia is that protein degradation exceeds protein synthesis, resulting in a net loss of protein in the dog’s body, contributing significantly to his weight loss as his muscle mass is stripped away. This net protein loss results in decreased cell mediated and humoral immunity, gastrointestinal function, and wound healing.

According to Dr. Ogilvie, the majority of weight loss in cancer cachexia is due to the depletion of body fat, which (like protein) gets broken down at an increased rate in the cancer patient. However, unlike carbohydrates and protein, an increase in dietary fat does not seem to benefit canine cancer tumors. Fortunately, the dog’s ability to utilize fats as an energy source is unimpeded.

One interesting consequence of the metabolic change: it appears to be permanent. Once a dog has cancer, the metabolic processes remain altered even if he goes into remission.

Adjust Your Dog’s Diet Accordingly

Understanding these metabolic changes can help us formulate a diet that maximally benefits the dog, and minimally benefits his cancer. Well-nourished patients not only exhibit greater overall health, they also display an increased tolerance of veterinary interventions (such as surgery, radiation, and chemotherapy), and an increase in immune responsiveness.

Dr. Ogilvie modestly points out that the “ideal” dog cancer diet is not yet known, but his thinking on the topic is way ahead of most veterinarians. He and his associates at Colorado State have shown huge progress in developing a diet plan that can reduce the effects of cachexia – nourishing the dog and not the cancer. The basic framework suggests that the diet should be comprised of a relatively low amount of simple carbohydrates, modest amounts of fats (especially omega-3 fatty acids), and adequate amounts of highly bioavailable proteins.

Numerous studies have demonstrated that a high-fat, low-carbohydrate diet contributes to a higher probability of remission (when given in conjunction with chemotherapy) and to longer survival time.

The evidence is so compelling, in fact, that Dr. Ogilvie and a team from Colorado State worked with Hill’s Science & Technology Center to create a dog food specifically formulated for the needs of the cancer-stricken canine, Hill’s Prescription Diet n/d. It came on the market in 1998 after almost a decade of study.

“This type of nutritional concept is something that’s backed up by literally hundreds of studies, both in lab animals and people, and in clinical trials with dogs,” says Philip Roudebush, DVM, Dip. ACVIM, a veterinary fellow for Hill’s. “Unfortunately, a lot of people don’t know that – veterinarians as well – but to me, it’s about as well validated a concept as we have in nutrition.”

Because the metabolic changes that occur in a cancer-afflicted dog are permanent, even if his cancer goes into remission, feeding this adapted diet may be necessary for the remainder of the dog’s life.

What’s In an Anti-Cancer Diet for Dogs?

While the experts don’t all advocate the same approach to nutrition and cancer, they do agree on one thing: don’t try this on your own. It’s essential that your vet works with you on formulating a diet that meets your dog’s specific needs, especially if your pet is undergoing any sort of additional treatment such as chemotherapy. Even supplementation is discouraged without the input of a professional.

But if your practitioner suggests you try an altered diet by preparing homemade meals, here are some of the things he might recommend.

1. All ingredients should be fresh, highly bioavailable, easily digested, and highly palatable, with a good taste and smell.

Many cancer patients lose their appetite, either due to their treatments or illness; these dogs must be tempted to eat, a lot.

Note: Veterinarians have a variety of pharmaceutical appetite stimulants that may be helpful for keeping an inappetent dog eating. The goal is to prevent anorexia and weight loss at all costs. If a canine cancer patient stops eating, the veterinarian should consider “enteral” feeding – using either a nasogastric tube (which goes through the dog’s nose and throat and into his stomach) or a gastrostomy tube (which is surgically placed in the dog’s stomach and emerges from the dog’s side). Such measures, while dramatic for the owner, can be of enormous value to the patient and are generally of short duration.

2. Organic foods.

Conventional veterinarians may beg to differ, but holistic practitioners of all kinds are quite comfortable with the numerous studies that link common chemical pesticides and fertilizers to cancer, as well as reproductive and neurological damage. Dr. Anne Reed, a holistic veterinarian in Oakland, California, recommends that her clients utilize organic meat as part of their anticancer diets. “Giving a dog as clean a diet as possible can only help,” she says. “I feel like the last thing the canine cancer patient’s body needs is to deal with the pesticides, antibiotics, and extra bacteria that tend to be in nonorganic meat. You don’t want their bodies to have to focus on clearing out toxins as well as fighting the cancer.”

3. Fresh, organic meats, either raw or cooked.

Fresh, clean, high-quality meat is both appetizing and highly bioavailable.

4. Fish-oil supplements.

Rich in omega-3 (n-3) fatty acids, which have been linked to tumor inhibition and strengthening the immune system, fish oil may be more readily absorbed by the dog’s body than a close cousin, flaxseed oil.

5. Vitamin C.

Known and used for its antioxidant properties, this vitamin can easily be given in pill form. Antioxidants neutralize free radicals as the natural byproduct of normal cell processes. In addition, antioxidants must be supplemented whenever omega-3 supplements are given.

6. Fresh vegetables.

Cruciferous veggies like broccoli and dark-green, leafy vegetables like spinach are healthy for any dog, but especially for cancer patients. According to the National Institutes of Health and the American Institute for Cancer Research, diets high in cruciferous vegetables – such as broccoli, cauliflower, cabbage, watercress, bok choy, among others – have been associated with lower risk for lung, stomach, and colorectal cancers in humans. According to the American Cancer Society, broccoli, in particular, is the source of many phytochemicals that are thought to stimulate the production of anticancer enzymes.

In addition, the fiber that vegetables provide is essential to maintain normal bowel health, which, in turn, is key to overall health. Pureeing the vegetables and mixing them into food may improve acceptance for some dogs, while others will be content to crunch them raw or lightly steamed.

7. Digestive enzymes.

Holistic practitioners often recommend these to help support the dog’s digestive abilities, especially during the transition to a new diet.

8. Garlic.

Small amounts, such as a clove a day, may be recommended. According to the National Cancer Institute, studies provide compelling evidence that garlic and its organic allyl sulfur components are effective inhibitors of the cancer process.

9. Safflower oil.

According to Lisa Barber, DVM, assistant professor at Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine, there is some anecdotal evidence that this oil can help achieve remission in patients with a difficult form of lymphoma, epitheliotropic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.

10. Limited carbohydrates.

If your vet promotes a raw diet, you might also look into pre-formulated offerings from companies like Primal Pet Foods and Steve’s Real Food. Their frozen offerings are convenient to store and easy to parcel out for meals.

Note: The costs for any of these feeding programs are not negligible. The packaged raw diets will run in the neighborhood of $45 – $50 per month to feed a 20-pound dog, while the Hill’s Prescription Diet n/d suggested retail price (which is subject to markup) is $1.50 – $2 per day for the same size animal, or $45 – $60 per month. The cost of homeprepared diets varies widely depending on the size of the dog, the type of meat used, and amount of supplementation.

Anti-Cancer Diet Details: What We Know and What We Don’t

A recent study coauthored by Dr. Ogilvie suggested using a diet with a ratio of less than 25 percent carbohydrate, 35 to 48 percent protein, and 27 to 35 percent fat, with more than 5 percent of the total food comprised of omega-3 fatty acids and more than 2 percent of arginine. (All these measurements apply to dry matter.)

Fish oil can be beneficial in an anticancer diet as both a fat source and a source of omega-3 fatty acids. These acids, also known as n-3 acids, have been linked in studies to tumor inhibition and enhancement of the immune system. Antioxidants are essential whenever n-3 fatty acids are used.

There has been much discussion of the potential benefits of other nutrients in an anticancer diet. Antioxidants such as vitamins C, E, and A have anticancer effects. Selenium, vitamins A and K3, arginine, glutamine, and garlic have been shown to be beneficial in some experimental settings. While promising, there is less evidence to support specific applications for these nutrients, although some veterinarians hedge their dietary recommendations and include these nutrients in some forms and amounts.

Feed Home-Prepared or Commercial Food to A Dog with Cancer?

If ever there was a good reason to feed a commercially prepared food, this is it. Feeding a commercial anticancer diet such as Hill’s Prescription Diet n/d, formulated with the assistance of Dr. Ogilvie and his associates at Colorado State, is a vast improvement on continuing to feed a dog’s regular kibble.

However, many holistic veterinarians – who, by and large, are more amenable to using nutritional therapies to treat many health conditions – recommend feeding canine cancer patients a home-prepared diet that meets Dr. Ogilvie’s basic anticancer, pro-dog outline.

For example, Anne Reed, DVM, a veterinarian at Creature Comfort Holistic Veterinary Center in Oakland, California, suggests that her clients prepare a diet that includes meat, vegetables, fats, and limited grains, as well as supplements such as vitamin C, garlic, and digestive enzymes. (Dr. Reed also uses other anticancer agents such as artemisinin, and Chinese herbs.)

Some veterinarians, including Reed, advocate a raw-food approach – although she’s careful to qualify this. Unless a client has experience preparing raw-food diets, Reed recommends preformulated commercial raw diets, such as those made by Primal Pet Foods and Steve’s Real Food, which are easier to handle and are nutritionally complete and balanced. But she doesn’t recommend raw food for every dog. “If a dog is on chemotherapy, radiation therapy, or very high doses of Prednisone or things that suppress the immune system, I’m very, very careful with raw food diets,” says Dr. Reed.

Nutritional Therapy for Cancer Treatment is Still A Radical Idea

Despite the very promising research in treating and supporting canine cancer patients with nutritional therapy, it’s not yet a cornerstone of conventional veterinary cancer treatment. “I believe that most veterinarians, including oncologists, recognize that diet can play an important role in moderating disease,” says Lisa Barber, DVM, Dip. ACVIM, an assistant professor at Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine. “However, how this applies to clinical practice is unclear.”

Dr. Barber doesn’t advocate a wholesale change in diet in response to the news of cancer. “I tend to discourage owners from indulging their pets with home-cooked meals at the time of initial diagnosis,” she said, in part to avoid a pet getting used to a tempting diet. “If pets are given ‘tasty’ foods when they are feeling well, it will be more difficult to tempt them to eat when they are feeling poorly.”

Barber recommends a high-quality commercial diet supplemented with fruits and vegetables and encourages clients to consult a board-certified nutritionist to devise a sound, balanced feeding plan. Like many conventional veterinarians, she is averse to diets that include raw meat, citing fears of nutritional imbalances and of pathogenic bacteria such as E. coli, which can strain cancer patients’ immune systems.

Are Pet Lovers Leading the Anti-Cancer Diet Revolution?

However, owners who are desperate to do anything and everything for their beloved companions often do their own research, looking for more options.

Steve Drossner of Philadelphia became one such owner when his German Shepherd Dog/mix, Ginger, was diagnosed with hemangiosarcoma, a cancer that affects blood vessels. A tumor on Ginger’s spleen ruptured, and caused her to collapse.

After the spleen (and tumor) were removed, Drossner’s veterinarian felt that chemotherapy should be the next treatment – although the vet could make no promises regarding the treatment, since hemangio-sarcoma is such an aggressive, fast killer. After consulting with a holistic veterinarian, Drossner decided to skip the chemo, and instead, put Ginger on a home-prepared anticancer diet of cooked free-range chicken, brown rice, olive oil, organic vegetables, and supplements.

Although Drossner bemoans the expense, he doesn’t begrudge his dog the menu, which has helped keep Ginger alive for more than two and a half years. “Free-range chicken is $8.49 a pound,” he says. “It costs me $11 to $12 a day to feed her, but I really have no other options. I feel that if I made any changes to Ginger’s diet and she took a turn for the worse, I’d never forgive myself.”

Anya Hankison, of Oakland, California, is another person whose dog was diagnosed with hemangiosarcoma. Tessa, Hankison’s eight-year-old Yellow Lab, was diagnosed with the cancer in May 2003. After an operation in which Tessa’s spleen, gall bladder, and one liver lobe were removed, Hankison consulted her conventional vet to discuss the next steps in Tessa’s treatment.

“The oncologist gave me a life expectancy of 30 to 90 days post-surgery,” she said. “He didn’t give me any hope whatsoever.” Diet was not mentioned.

Hankison consulted holistic practitioner Reed for a second opinion. Dr. Reed suggested trying a raw diet combined with supplementation. While she made it clear this approach would not be curative, she did tell Hankison that Tessa’s remaining days could be healthier and happier.

“I really liked that,” Hankison said. “Dr. Reed’s approach sounded so natural. I didn’t feel like I was getting in the way of the natural course of life, and yet I was hoping to prolong it and give Tessa the best quality of life possible.”

Hankison took Dr. Reed’s suggestions to heart and transitioned Tessa to a raw-food diet, beginning with cooked meat and graduating to meals made up of raw, organic chicken, steak, hamburger, or buffalo meat, a variety of vegetables including broccoli, spinach, and carrots, and a range of supplements and Chinese herbs.

It wasn’t an easy change. “Dealing with raw chicken is hard, unless you’re buying just the breast. If you’re feeding a 70-pound dog twice a day, it can get really expensive,” says Hankison. Finding the organic meat was time-consuming, necessitating several trips a week to a nearby Whole Foods Market. Simply preparing meals for Tessa, who ate two of them daily, took 20 to 30 minutes.

Hankison also found it difficult to fit the supplements into her budget. She managed to find some generic substitutes and discovered that Oakland’s Chinatown offered better bargains than local naturopathic stores did, but the cost was still considerable. The challenge was exacerbated when Tessa had a bout of nausea and would refuse a meal.

“There were times where I’d have to make Tessa’s meal four or five times, and I’d have to take out one ingredient each time until she would eat it,” Hankison says. “When she wasn’t feeling well, I’d sometimes have to pare it down to no herbs, no salmon oil, and just chicken.”

Sadly, Tessa succumbed to her cancer on August 19, three months after her diagnosis, dying at home in Hankison’s arms. Although she survived only to the outer limit of her first veterinarian’s prognosis, Hankison believes the altered diet gave Tessa as much health as was possible in her last weeks and days. “Her energy levels were great. She felt really well, she looked healthy, and she healed (from her surgery) very, very well. Her quality of life was excellent, right to the end.”

Both Hankison and Drossner both say they have no regrets about trying the new diets, despite the expense and hassle. The results, they say, are worth it – happier dogs who can enjoy the time they have left, however long that might be.

Find A Progressive Veterinarian

No veterinarian worth his or her diploma would suggest that diet alone can cure cancer. The goal in anticancer diet management should be to maintain overall health, weight, and nourishment, which in turn will significantly assist the conventional veterinary treatments – all of which will help provide the best quality of life possible.

These are the stated goals of Hill’s anticancer diet – longer survival times, longer disease-free intervals, and improvement in overall quality of life – and they ought to be the goals of any veterinarian whose patient is fighting cancer.

Unfortunately, there are still numerous veterinarians in practice who are resistant (or just unhelpful) when questioned about a dietary contribution to cancer treatment. In these cases, our strong suggestion is to find another veterinarian to work with, fast.

C.C. Holland, a frequent contributor to Whole Dog Journal, is a freelance writer from Oakland, California.

Herbal Remedies for Treating Older Dogs

by Gregory Tilford

The sun has barely risen over the eastern horizon on a cold Montana morning, when a warm lick on the face awakens me from a dead sleep. I sit up slowly, my back aching from the yard work I did nearly a week ago. A whispered curse leaves my lips as a new shot of pain – from an old ankle injury – tells me that the skies are threatening to rain; it’s time to get busy stacking firewood before the first snow flies.

Another lick, this one a reminder, moistens my forearm. Willow, my 12-year-old Shepherd/Husky, wants to take an early morning walk on the mountain behind our house, which will be followed by her customary morning cookie.

In years past, Willow and I would hike far and wide. I’m always looking for herbs to photograph and study, and Willow always enjoyed our far-flung rambles.

Of course, at 12, Willow is a senior dog. Her joints are stiff and sore after an overlong walk. Her right leg wobbles after exercise, due to an old ligament injury. Petting her soft, graying snout, I tell Willow how aging really sucks.

At least for humans.

For humans, old age is as much a mindset as it is a physical circumstance. But to a dog, the thought of “yielding to the wheels of time” never occurs. Willow isn’t concerned about growing old. She doesn’t worry about her wobbly leg. She doesn’t even care about the egg-sized fatty tumor on her flank; she just wants to enjoy every waking moment with me – regardless of my moaning and groaning!

As a loving caregiver with a responsibility to provide Willow with the longest, happiest “dog’s life” possible, I must be careful not to let my worries of losing her interfere with her fun. That just wouldn’t be fair.

So instead of focusing all of my efforts on sheltering her from all possible harm, I try to provide her mind and body with everything they need to remain healthy, efficient, and fulfilled.

Although we cannot turn back the hands of time and may not be able to prevent the inevitable, a great deal can be done to assure optimum health and well-being during a dog’s later years of life.

Old age should not be viewed as a downhill slide to inevitable suffering and death. Nor should chronic disease be perceived as part of growing old. Each year hundreds of elderly dogs are put to sleep prematurely – not because they are deathly ill, but because their guardians can’t get past their own fears of watching their companions grow old and die a natural death. Granted, it’s difficult to live in anticipation of a companion’s death, but with all things considered, this is really our problem, not theirs.

The fact that an animal is growing old and becoming more susceptible to illness does not automatically predispose him to chronic disease – it just means that he needs some added care and attention. With your loving support, your old best friend can enjoy life right up to his last day.

The senior diet

Each month of nutritional deficiency can trim healthy years from the latter end of your dog’s life.

Please think about that last sentence for a few more seconds, and then get to work at improving her diet, because many chronic problems seen in elderly dogs are very often related to nutritional deficiencies.

Regardless of how good the food is you are feeding, the fact remains that as your dog’s body ages, its functional abilities to utilize food and properly eliminate waste will begin to decline. Liver problems, chronic renal failure, diabetes, arthritis, and hip dysplasia, as well as neurological problems (such as canine cognitive dysfunction) are just a few of the problems that may be prevented by not only improving the quality of her diet, but also the efficiency by which your dog’s body can utilize it.

Diet should be frequently reevaluated and adjusted as needed to accommodate any reduction in digestive efficiency. The food must be highly digestible and rich with vitamins, chelated minerals, meat proteins, and fats that are easy for her aging body to assimilate.

Depending on your senior companion’s condition and lifestyle, a vitamin/mineral supplement may be needed. Digestive enzymes and probiotic (beneficial bacteria) supplements should be added to each meal to optimize nutrient absorption and assist with the breakdown and elimination of waste.