When I first noticed Shadow’s eyes staring into the pond, I thought she saw something in the water. It looked like her eyes were following fish swimming, except there were no fish in our little pond.

I looked closer to see if perhaps there were some water bugs. Then I stood back and watched my new pup. Her eyes were following the ripples, or perhaps the light sparkling off of the ripples. I watched her eyes go from fixation to glazing over into an almost trance-like state. “Oh, no,” I thought. “It can’t be!” I tried to distract her, which worked for a minute, but then she was right back at the pond, chasing the sparkles on the water. This incident confirmed my suspicions: My new dog was showing strong signs of canine compulsive disorder.

Also called compulsive behavior disorder, this is a mental health disorder “characterized by the excessive performance of repetitive behaviors that don’t serve any apparent purpose,” explains Dr. Jennifer Summerfield, a veterinarian and professional dog trainer who specializes in treating behavior problems. Common compulsive behaviors include spinning or tail chasing, licking or self-mutilation, flank sucking, chasing lights or shadows, fly snapping, or hallucinatory prey chasing/pouncing behavior. It is considered similar to obsessive-compulsive behavior (OCD) in humans.

What’s Normal Repetitive Dog Behavior?

Lots of herding dogs and other types of “high drive” dogs have what I like to call the “do it again, do it again, do it again” trait – doing behaviors over and over again. But this isn’t necessarily canine compulsive disorder.

Dr. Summerfield says that some repetitive, apparently non-functional behaviors can be perfectly benign. Many dogs spin in circles when they’re excited or will happily retrieve a ball as long as you continue to throw it. Lots of dogs will fixate on squirrels or birds in what many consider to be an obsessive manner. Dogs may also pace back and forth in the yard when they’re bored or spend a lot of time carefully licking their paws during downtime in the evening.

In contrast, “a behavior like this crosses the line and becomes a problem when it begins to interfere with other normal activities like eating and drinking, resting, playing, and being social with family members,” Dr. Summerfield says. “In many cases, it may also be difficult to distract the dog or get him to stop once he’s started to engage in the behavior.”

This was why the incident with my dog by the pond clinched my suspicions. Prior to this, I wasn’t sure if what I was seeing was simply an extremely high-energy herding-dog puppy, or one who was exhibiting signs of a serious problem. Shadow would incessantly chase her tail and sometimes would attack her rear foot as if it weren’t attached to her body. And she was in constant motion – always moving and having a difficult time settling even when she was clearly exhausted. But the fact that distracting her from these activities worked for only a few brief moments brought home that this was much more than an over-the-top puppy.

In the 20 years I’ve been working with dogs, including those who exhibit problematic behavior, I had seen compulsive behaviors to this extent only a handful of times.

Canine Compulsive Disorder in Dogs: It’s a Brain Thing

According to Dr. Summerfield, studies have shown that abnormal repetitive behaviors (including the clinical disorder of OCD in human patients) are associated with abnormalities in a particular area of the brain. These areas are called the cortico-striatal-thalamic-cortical (CSTC) loop.

Essentially, this is a circuit connecting the cerebral cortex to deeper structures in the brain, those that are involved in information processing and in controlling motor function. There is a pair of complementary signaling circuits called the direct and indirect pathways that form a part of the CSTC loop. The direct pathway is involved in initiating or enhancing movement, while the indirect pathway stops or inhibits movement.

“When it comes to starting and stopping behaviors, you can think of the direct pathway as the gas pedal and the indirect pathway as the brake,” Dr. Summerfield says. “In patients with compulsive behavior disorders, these pathways are out of balance – the direct pathway becomes more active, and the indirect pathway becomes less active. As a result, the affected animal (or human patient) may get ‘stuck’ in repeated loops of behavior and have a hard time stopping what they’re doing.”

Dr. Summerfield says, “Of course, this is almost certainly not the whole story! The brain is incredibly complex. There is some evidence that different types of compulsive behaviors (spinning or tail chasing vs. licking or sucking objects vs. hallucinatory prey chasing or fly snapping, etc.) may involve slightly different mechanisms and changes in the activity of different neurotransmitters. So there’s a lot more to learn here!”

What Causes Canine Compulsive Disorder?

Studies indicate that there are likely a variety of causes and contributors to repetitive, compulsive behaviors in dogs, including medical issues. So much is still unknown, but here are some of the more widely considered causes:

Genetics

While any breed may develop a compulsive disorder, there are certain compulsive behaviors that seem to be more common to specific breeds. For example, Dobermans may have a higher risk of flank sucking, Bull Terriers are more likely to spin or tail chase, and Border Collies are more likely to stare at shadows and/or flickering lights.

Response to Stress

Animals (including dogs) that are living in situations where they cannot express normal behaviors, such as those living in kennels for long periods of time, can develop stereotypic behaviors such as pacing, circling, or spinning.

Response to Arousal or Frustration

Different from animals who are living in poor conditions or who are under stress, some repetitive behaviors seem to be triggered by extreme arousal or frustration.

Dogs who become light-obsessed after playing with laser pointers may fall into this category. The theory is that when a dog chases a laser pointer, he cannot complete the normal predatory sequence by actually catching or grabbing the “prey” in the same way he can with a ball or toy, or a real rabbit or squirrel. This can cause an excessive amount of frustration and can cause the dog to constantly search or wait for the light to appear.

Medical Problems

Sometimes repetitive behaviors are not caused by a compulsive behavior disorder, but are instead the result of a different underlying medical problem.

Spinning or tail chasing may be caused by things such as anal gland problems, pinched nerves, or spinal problems. Dogs who compulsively lick or chew at certain parts of their body may have allergies, a skin infection, orthopedic pain, or other physical sources of discomfort. Both spinning and fly snapping can be neurologic, with a variety of possible underlying causes such as brain tumors, seizure disorders, or hydrocephalus (buildup of fluid in the brain cavities).

In addition, a medical cause such as an allergy may initially trigger a behavior that then develops into a compulsive disorder; conversely, a compulsive behavior such as licking or flank sucking may cause a physical problem such as pain or an infection.

Help for Dogs Affected By Canine Compulsive Disorder

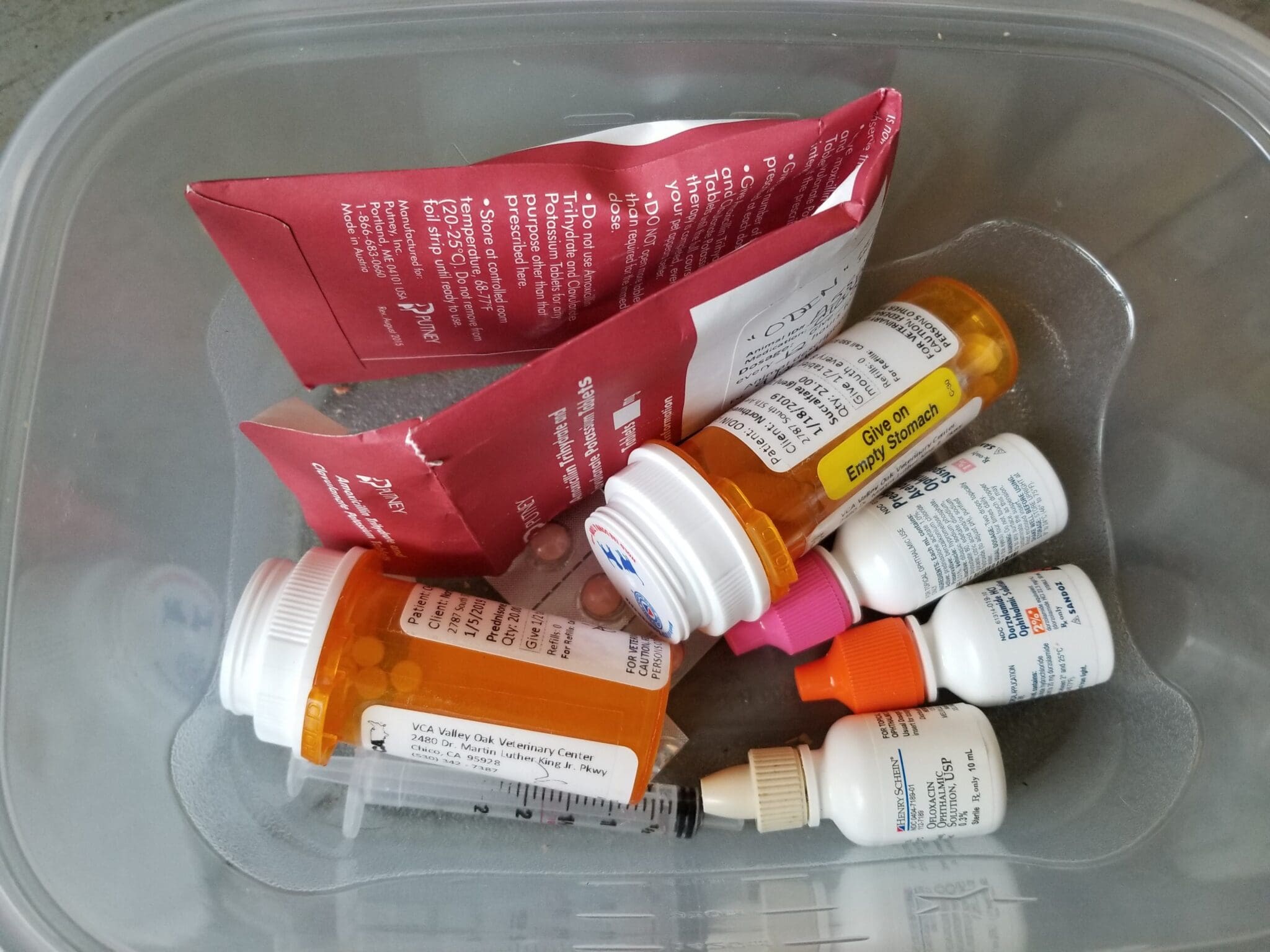

Unfortunately, the underlying cause of compulsive issues is not always easy to diagnose. This is why a trip to veterinarian or veterinary behaviorist is a good place to start.

If the veterinarian suspects medical causes, says Dr. Summerfield, then he or she may recommend diagnostic testing or imaging studies. If testing is not feasible, in some cases, a trial course of a steroid or pain medication might be used to see if there is any response. If the behavior improves on these medications, this is a strong indication that there is an underlying physical problem rather than “just” a compulsive behavior disorder.

Helping dogs with compulsive behavior disorder live a more normal life takes a holistic approach – generally a combination of lifestyle changes, behavior modification, and medication is needed. A dog’s treatment plan might include:

1. Avoiding known triggers.

As much as possible, it is important to avoid the triggers for the compulsive behaviors. For example, for one dog avoiding triggers meant not going on walks at night when headlights flashing on fencing would trigger light chasing. Avoiding triggers may be short term until medication and/or behavior modification kick in, or it might be ongoing.

2. Interrupting and redirecting if the compulsive behavior occurs.

According to Dr. Summerfield, interrupting the behavior should always be done in a neutral manner and the dog should be redirected to some other activity.

This sounds pretty simple, but it can sometimes be very difficult to get a dog who is doing a repetitive behavior to stop. Moving the dog into another room or even crating them with a meaty bone or food-stuffed Kong can sometimes help.

3. Teaching an alternative response.

Sometimes the trigger is something that can’t be avoided, but you may be able to teach your dog to do something other than the repetitive behavior.

If your dog spins when frustrated, for example, you may have success with teaching him to run into his crate or go grab a toy instead. For a dog who is triggered by overexcitement or anxiety, teaching him to settle on a mat and then reinforcing it throughout the day so he is less overall excitable can help.

4. Creating a structured daily routine.

Because predictability lowers stress, doing specific things at set times can be very helpful for dogs who are anxious. In addition, compulsive behaviors are sometimes triggered by frustration, and routine can help eliminate frustration.

5. Increasing exercise.

Increasing exercise may help, especially if the repetitive behavior issues stem from boredom or frustration. Exercise also increases serotonin and other chemicals in the brain, which may provide some benefit.

6. Providing brain stimulation.

Training exercises using positive reinforcement techniques may help dogs who have anxiety that is being relieved by the compulsions.

Puzzle toys and food games may help engage a dog’s brain so that he is less likely to engage in the repetitive behavior. Giving your dog outlets for normal dog behavior, such as allowing her to sniff on walks or play with dog pals, also can help some dogs.

7. Talking with your veterinarian or a veterinary behaviorist about medication.

Many dogs with a compulsive behavior disorder will benefit from medication.

When Shadow was first diagnosed, I wanted to see if we could make headway without medication, but my veterinarian cautioned us against waiting. Compulsive behaviors tend to get worse over time, she said, and the longer the problem goes on the more difficult it is to modify. On our veterinarian’s recommendation, we started Shadow on fluoxetine (Prozac) and were amazed at the positive benefits in just a few short weeks.

Does Canine Compulsive Disorder Get Better?

Compulsive behavior disorders are tricky to diagnose, work with, and live with. “In many cases (though not always, unfortunately) the problem can be significantly improved with diligent management, training, and medication,” says Dr. Summerfield. “However, most dogs with a history of compulsive behavior issues will always have this tendency to some degree, so in most cases some degree of continued management will be needed for the life of the dog.” Dr. Summerfield says that unfortunately, even with intensive management and treatment, some dogs simply don’t get better.

The prognosis may depend on several factors, including:

- How quickly the problem is properly identified and addressed.

- How easy or difficult it is to resolve the underlying issue or avoid the triggers.

- How easy or difficult it is for the dog’s people to follow the recommended behavior plan.

- How well the dog responds to behavior medications.

Canine Compulsive Disorder Improvements Take Time

We have been very fortunate with Shadow. We identified that there was a problem quickly, and we had a great veterinary team to help us take the steps needed. Shadow responded to medication and to behavior modification, and we were able to make some lifestyle changes that helped, too. Within a few months of starting treatment, she showed signs of improvement.

Now, a little over a year later, Shadow seldom engages in compulsive behaviors, and she has become a pretty normal high-energy adolescent herding dog.

A long-time contributor to WDJ, Mardi Richmond is a dog trainer, writer, and the owner of Good Dog Santa Cruz in Santa Cruz, CA.

Special thanks to Dr. Jennifer Summerfield for her help with this article. Dr. Summerfield is the author of Train Your Dog Now! Your Instant Training Handbook, from Basic Commands to Behavior Fixes, and Dr. Jen’s Dog Blog.