I first spotted Otto in a jail-mugshot-type photo on my shelter’s website in June 2008. My husband had just agreed that we were ready to have a dog again, three years after the loss of my much-adored Border Collie, Rupert. Can you believe that it took three years of only fostering for the shelter and dog-sitting for family and friends before I had recovered from the loss of Rupert to seriously consider owning a dog again? But within minutes of my husband’s agreement that it was time, I spotted Otto’s photo and emailed the shelter to ask if they would hold him for me – make him unavailable to others – until I could get there the next day.

Truthfully, there were two dogs I was considering: Otto, and a young hound-mix. But Otto, then an estimated 7 months old and a friendly, if somewhat reserved scruffy-faced guy of about 40 pounds, was the one I chose to bring home “for a trial” – and of course, he never went back to the shelter. My husband mock-threatened to send him back several times in the first few days that we had him, as Otto spent any unsupervised minute digging holes under any plants we watered in the yard. It took me those first few days to realize he was just hot and looking for a cool place to lay down, and I ran out to get all the materials needed to build him a nice big damp sandbox in the shadiest corner of our yard. Once he had a legal place to dig a big hole and lay in it, our ornamental horticulture was safe.

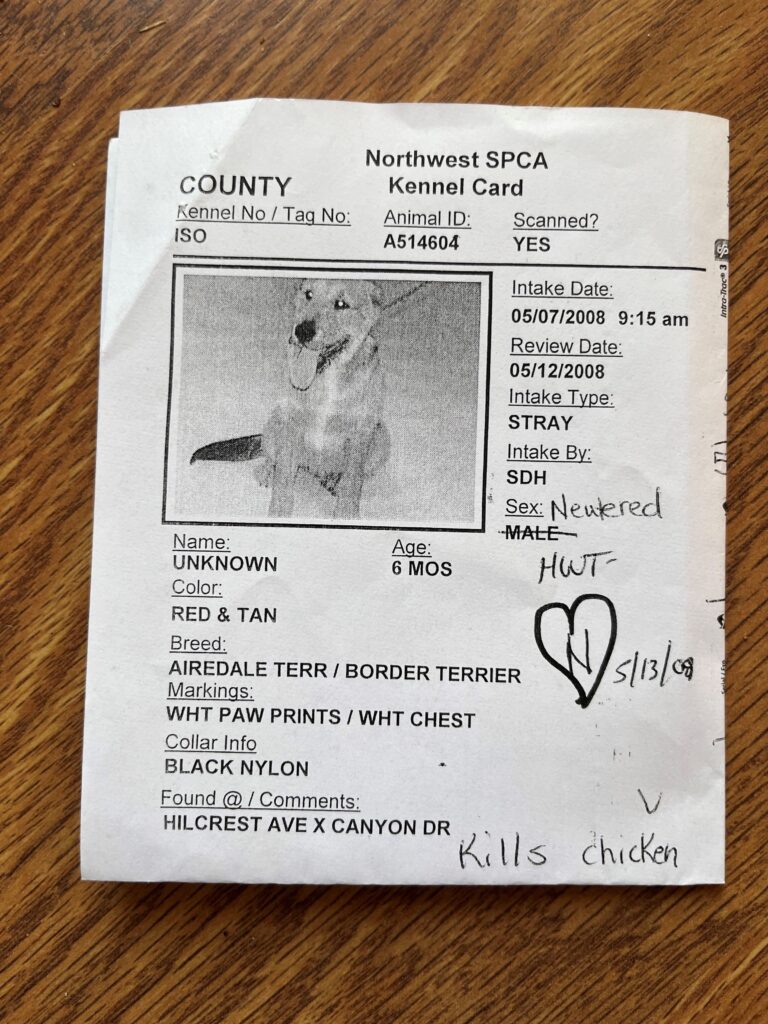

The digging wasn’t the only behavioral challenge we dealt with in the early years, though it was the most easily resolved. It became clear that Otto, who had been brought into the shelter after being found in someone’s chicken coop (with dead chickens), had probably gone stray or been dumped at an early age. He had good street survival skills – he could (and would) pick and ripe blackberries from wild vines, and made a beeline for any fast-food bags or other food-smelling trash on the street – but he didn’t know anything about living in a house, did not like being in a car, and was uncomfortable with humans in the first couple of years we spent together. The microwave beeps, vacuums, doorbells, and the Geico caveman on the TV all elicited barking and a hasty retreat from the house. (The caveman triggered the most dramatic reaction; he never seemed to pay attention to the TV, but when he saw that hairy guy, he leaped to his feet barking and growling.) Most of that faded away with time, but his phobia of slippery floors persisted through his lifetime.

And despite the shelter’s warning on his cage card that he “Kills chicken” (a typo that will make me laugh until the end of my days), he never killed or even chased any of my free-range chickens. By the time he was 3 or 4 years old, the slippery-floors quirk was about the only thing keeping him from perfect sainthood – but surely saints have quirks, too?

He was always a night owl – probably because he also hated the heat his whole life, and where we live is hot from June well through September. In all but the coldest months, he preferred to sleep outdoors, at least for a few hours. To be let out, he would come and pant loudly just outside my (open) bedroom door – he thought the floor in our hall was too slippery to attempt in all but the most dire emergencies. To be let back inside, he would give the front door one careful scratch of a front paw – so careful that the door is dirty but not scratched. In response to that sound, I can walk to the door to let him in or out in my sleep, and have done just that thousands of times in the past couple of years, as he grew more and more restless and uncomfortable with pain and a bit of nighttime dementia. But as unreasonable as his desire to go in and out several times a night could be at times, his request was always polite (and respected).

Otto accepted a never-ending parade of foster dogs and taught countless foster puppies how to introduce themselves to adult dogs respectfully. He never hurt a single puppy, though he would roar a terrible roar if they didn’t heed the early warning rumbles of disapproval at an over-eager approach. He would beat a hasty although dignified retreat when vastly outnumbered, but if a lone puppy who was calm and polite came toward him, she would be rewarded with a slowly waving tail and an approving sniff – but that’s it. He wasn’t here to play with puppies; they could follow him around the property if they behaved themselves, but that’s all the familiarity they could brook. Even Woody, the Pit Bull-mix who came to our home seven-plus years ago as a 3-week-old foster puppy (along with eight siblings and a dog-aggressive mother) and never got sent back to the shelter, who grew to be taller and heavier and stronger than Otto but never stopped seeking Otto’s attention and approval, was treated like a rude puppy: “If you calm down and behave yourself, you can be near me. If you act like a fool, you will be treated as such.”

Somehow, his boss-like but benevolent demeanor inspired instant deference in every dog and puppy he met. Recently, I was visited by a friend and her standard Poodle, who can be a bit of a bully with other dogs. I held the Poodle’s leash, and was ready to intervene quite robustly if the Poodle pulled any crap whatsoever with my wobbly old guy – but that’s not how Otto presented himself to newcomers. As rickety as he was, he drew himself up, head high, tail waving, chest rumbling – and damned if that bully Poodle – who was a bit of an ass with friendly, happy Woody – didn’t immediately defer and disengage, putting his head and tail down and keeping his eyes elsewhere. Even he knew not to mess with the king.

Otto was the first dog I owned who I trained only with positive-reinforcement-based methods – and I think that was critical to helping him gain confidence in those early years, and develop into the unfailingly polite and responsive dog he was for the rest of his life. He loved training – he would insert himself into any training session with any dog he overheard me training, and compete for the rewards like an overeager third-grader who knows all the answers in math class. Somehow, this was endearing rather than annoying, and it certainly helped model the desired behaviors for the slower pupils I was actually working with – social learning is a thing!

Speaking of social learning, he taught Woody, Boone, and many of my friends’ dogs his greatest skill: standing still to pose for the camera. His portraits are innumerable and (I think) stunning. His calendar and magazine appearances are countless.

His other impressive skill was a recall that was immediate and enthusiastic, and even though he couldn’t hear me calling him in these past few years, he could still hear handclaps, which I would use to get his attention, and when he would turn to look for the source of the clap, a hand signal would still bring him as fast as he was able.

That wasn’t very fast, lately. He was on four different medicines for his arthritis pain, and watching him walk was certainly painful for me. And he couldn’t trot anymore – but he could and still would swing into a lope for short distances when he was really fired up, like when he spotted one of his imaginary enemies, the trucks of UPS, FedEx, and the United States Postal Service. (Our carrier liked to egg him on, and would often honk or call him as she drove by.)

Given his more or less constant arthritis pain, he suffered with the heat last summer – heat that lingered and worsened as the summer wore on. In September, he grew so miserable that I actually made an appointment for euthanasia for the following week. He liked being cool, but hated being indoors; he wanted to be outside, but it was hot. Panting, he’d ask to go out and then back indoors again multiple times an hour, seemingly forgetting why outdoors was not a viable option each time. Providentially, the heat finally broke that weekend, and by the time the vet arrived, it was 20 degrees cooler and he acted like his old self: dignified, gracious, interested. We adjusted his pain medication protocol and he lasted nine more months.

This winter and spring were kind to him. We had tons of rain, which came with mild temperatures; he often slept through rainstorms in his sandbox under its patio umbrella. I don’t think we had a single freezing night. And then in May, we had one or two warmish weeks, which immediately increased his discomfort, but then it cooled down again in an atypical way for this area. It’s almost as if the world was conspiring to keep him here longer. I started fantasizing that he’d make it to his 16th birthday. But it was a race against time, because his legs steadily lost muscle, particularly in the rear end, and his joints grew more and more lax. Viewed from behind as he walked, he resembled a puppet being controlled by an inattentive puppeteer who kept lowering the puppet’s control apparatus – his legs buckling and twisting in ways that hurt to watch. And he started to fall, and worry about falling. After a fall, he would struggle to get back to his feet and visibly resent any help I gave him; it seemed an affront to his dignity. He started holding his ears back and down almost permanently, panting in a tense grimace as he made his habitual, determined rounds of our property.

The last straw was the failure of his appetite. About a week ago, he started turning down meals. I tempted him with a can of something, which would work for one meal, and he’d refuse it at the next meal. He turned down raw eggs (an old favorite), scrambled eggs, and leftovers from our meals. He would still take my most reliable secret weapon – Stella and Chewy’s Meal Mixers – if I fed them one at a time like a treat, but when I bought some in patty form and put them in his bowl as a meal, it was a no-go. Without him eating, with the temperatures rising, I made another appointment.

I have heard many people say – hell, I’ve said it myself to several of my friends – that it’s better to give our beloved canine friends the permanent sleep too soon than too late, but that was before I had to make that agonizing decision myself. I am not sure I will repeat that advice as easily again. I didn’t want such a good dog to suffer, and told him so again and again as I held him and stroked that smooth hair on the top of his head, as the veterinarian made the final injection. But I miss him so much that I am not sure I can judge whether it was the right thing to do right now. No matter what I decided was going to cost me dearly. Paying for the lifetime of love and connection and fun and comfort he gave me should be costly; it was priceless.