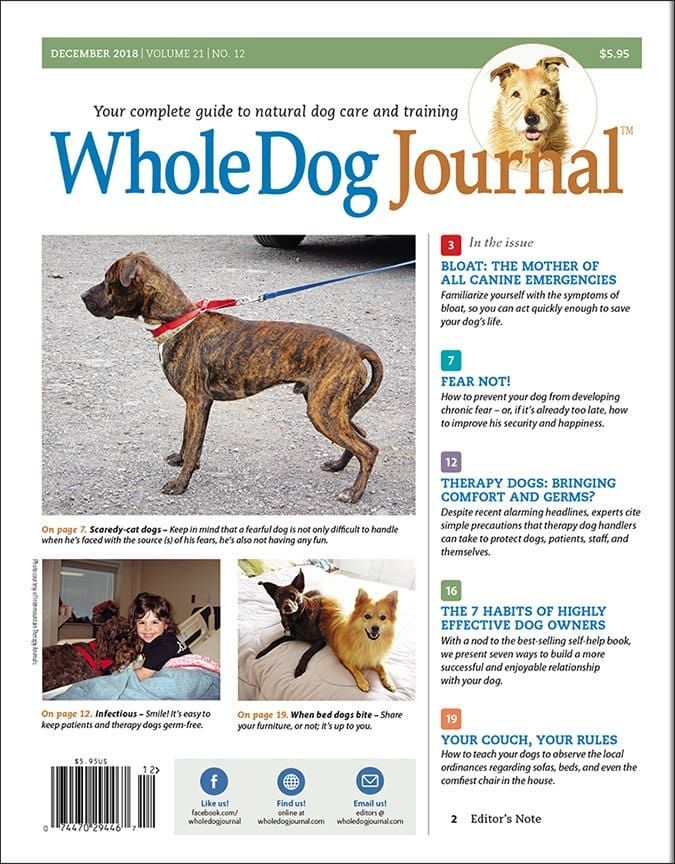

Wednesday, November 7

A week ago, my biggest concern was getting my foster puppies adopted. To that end, I managed to get an invitation to our local TV station, so they could be the “Pets of the Week” – a fun bit of video that airs on the broadcast news and can also be shared via social media. I bathed all my foster pups and picked the four most personable of the seven remaining, and took them to the station early. I brought an exercise pen and set it up in the station’s lobby, had all the pups potty outside, and then trooped them into the lobby to wait for the station’s meteorologist, Cort Klopping, to be free to tape the segment. At least a dozen employees of the station came out to pick up and hug the pups and pose for photos and send texts to friends they thought might need a pup. The puppies behaved SO well, and I thought it was a big success. I couldn’t wait for the clip to be aired and shared and all the pups to fly off the shelves, so to speak.

Thursday, November 8

The next morning, I dropped the pups at my local shelter (in Oroville, California) with high hopes a few would get adopted, and in fact, a couple came in and adopted one puppy that morning. But almost immediately following came the news that a forest fire had started near the town of Paradise, California, about 20 miles away. Even without TV or radio news, the fire was apparent; a huge column of smoke dominated the sky. Most foreboding was the fact that the smoke plume was going sideways; this meant there was a strong wind pushing and feeding the fire. By midday, the “adopt the puppies” project was forgotten; all local media and social media was about evacuation, emergency shelter sites for evacuated people and animals, and rescue. This fire had a name, the Camp Fire; it was so named after the road closest to the place where it started, Camp Creek Road.

Just a few months ago, on July 23, there was a huge and deadly fire near (and then in) Redding, California, a city that is 110 miles north of me. That fire burned almost 230, 000 acres and more than 1,000 homes; eight people died in the fire, including three firefighters. It wasn’t 100 percent contained until August 30. It was this fire that was fresh in my nightmares when I wrote an editorial for the September issue of WDJ, pleading with owners to be ready to evacuate with their pets in case of any emergency.

By the afternoon, I was rushing around making own preparations to evacuate. There were high winds that day and the fire was blowing up and moving FAST – but sideways from east to west; I’m south and a bit east. For me, it wasn’t a matter of “LEAVE NOW,” just, “Get ready to leave soon, if need be.”

I brought my foster puppies to my home, so that they and my own two dogs were in the same place (and an additional four miles farther away from the fire). My husband and I filled up our car and truck with gas. I found all my dog crates, checked the connections, and padded them with blankets. Grabbed a plastic bin and stuffed it with dog food, bowls, and extra leashes. Filled a few water jugs and put them in the truck. I have extra dog collars that have my phone number stitched into the fabric, and I put one on each of my dogs and the puppies. From my office, I grabbed the folders that have all my dogs’ health records, my computer (a Mac mini, very small), my backup drives, and my cameras and chargers. At home, I watered the lawn and blew leaves away from the outbuildings. At last we felt sort of ready to go. We tried to gather what news we could, but it was tough; our internet had gone out and even the cell phones were getting only intermittent reception.

On the way back from my last trip to town, I saw the body of a dog who had been struck and killed (it was obviously dead) on the side of the road I live on. I made a mental note to go back in just a bit to go see if the dog had a collar or ID. It made me so sad to think about the fact that the dog had likely been a victim of someone’s rush or panic in the face of the fire.

But it was right about that time that I started getting texts from my good friend (and frequent model for WDJ), Sarah Richardson, who owns a boarding, training, and daycare facility called The Canine Connection in Chico, the next town directly in the path of the fire. Evacuation orders were being issued for the part of town immediately next to where her business is located – less than a mile from her – and she had 20 dogs boarding at her facility at that moment. Taking a page from the director of my local shelter, who had the foresight to evacuate her shelter a full week before she was ordered to when we had the Oroville Dam disaster almost two years ago, Sarah decided to pre-emptively evacuate her facility. She didn’t want to have to move 20 client dogs (and four of her own) in a panic. She rented some vans and her staff started loading dogs and crates into vehicles, and they hit the road with a plan to head north in a convoy of five vehicles containing staff members and dogs). Terrible traffic and a lack of options in that direction made them pause at a rest stop to reconsider where to go. I invited Sarah and the rest of the convoy to my house.

Friday, November 9

They arrived around 2 a.m. Her staff walked the dogs and made sure everyone got to go potty and have a drink, and got the dogs settled in crates set up in an outbuilding on my property. By the time that was done, it was nearly dawn.

I took an opportunity to slip out and drive down the road to where I had seen the dog’s body. It was still there, a gorgeous black Labrador. She was wearing a collar with ID, but not a phone number for the owner. I contacted someone who I knew would know the dog, and the owner was notified. I will tell you more about this some other day; all I can say right now was that the loss of this dog was unbelievably tragic and I started crying that morning and I cry every time I think about it to this day. The dog’s death has not yet been announced by the owner, though it will be soon, I think. Someone was dispatched to pick up the dog’s body and arrange for her cremation.

It was surreal. I came back from this errand crying, but the day (Friday) was developing into real beauty. The sky directly overhead was robin’s egg blue, and the sun came out and warmed us all up as Sarah’s employees took the dogs out in small groups to potty and play. My dog Woody was beside himself with happiness, greeting each new group of dogs (boarders and regular clients of Sarah’s dog daycare) as they were released from their pens; he got to be the “play concierge” for the day and was thrilled, leading the groups on wild runs around my two-acre field. Sarah, her employees, and I were all stripping off sweatshirts and down vests until we were all in just short-sleeved T-shirts and soaking up the sun.

Sarah and her facility’s manager had been on the phone, leaving messages for the owners of all the boarded dogs, letting them know that the facility had been evacuated and their dogs were safe. Two sets of owners were near enough that they came to my house to collect their dogs; they were all incredibly grateful to Sarah and her staff for keeping their dogs safe.

I checked in with the director of my local shelter. We agreed that any adoptions would not be happening, and I would hold onto my foster pups for the time being.

But as the hours ticked past, the giant cloud of dark smoke gradually crept across the sky until it blotted out the sun. Ominously, the temperature dropped about 25 degrees in an hour. The playgroups sort of ground to a halt as we took in the latest fire news: that the firefighters had lit backfires on the edge of Chico to prevent the first from being blown any further into the city limits, and that the evacuation mandate for the area where Sarah’s business was located had been lifted. We loaded all the crates back into the cars and vans and The Canine Connection hit the road back to Chico. It was back to just me and my husband, my two dogs, and the six remaining foster pups.

I got a phone call from the director of my local shelter; she had been in touch with some shelters and rescue groups from elsewhere (places not threatened by the fire). Several were sending vehicles and volunteers to our area to transfer some of our adoptable animals to these out-of-area adoption centers. This would free up space in the shelter to receive animals we were sure to expect from the fire zone. She said a group coming from a town about an hour away wanted my puppies specifically, so I should bring them to the shelter. I burst into tears. First, the dog who had been killed on the roadside, and now I had to say goodbye to ALL of my foster pups in one fell swoop. I had wanted them adopted, but not like this.

But I’m just a foster provider; they aren’t my pups. I loaded them into my car and brought them into the shelter, kissing each one again and again as I carried them to their run, as I had done every day for the past few weeks. They were perfectly comfortable there, and all settled into their later afternoon nap. One of the kennel attendants asked me if I was all right; I could only wave miserably and sob, “My puppies!” He smiled sympathetically and kept moving. They know me well.

At 5 pm, the director called me again and said, “The rescue came and went without your pups; they are going to come back tomorrow and take them then.”

“I’m on my way!” I jumped with glee. What a weird reversal from just a couple days before. I wanted those pups OUT of here; now, I couldn’t bear for them to leave. If this sounds positively bipolar, it’s due to the raw emotions that accompany a disaster. Our internet service was restored just in time to receive news reports coming in of fire-related deaths and thousands of people and hundreds of animals evacuated. Social media was full of pleas for help rescuing hundreds of animals that had not been evacuated, but left behind the morning prior as people went to work before the fire had been reported and grown huge. The black Lab’s death on my road made the number of fatalities personal and vivid. Just thinking about leaving my dogs home for a trip to the store or something, and then being unable to go back to rescue them from a fire – it just stops the breath in my throat. So I bolted to the shelter to grab my foster pups and kissed each one all the way back to my car.

Saturday, November 10

In my area, there is a group we call “nav-dag.” The name is an improper pronunciation of its initials, which stand for the North Valley Animal Disaster Group. These folks – all volunteers – organize and staff the local response to fires, floods, horses stuck in ravines, cattle-truck turnovers, and anything else involving animals and disasters. The day of the fire, NVADG had sprung into action, mobilizing its volunteers at two established sites where, historically, animals who have been evacuated or rescued from local disasters have been housed and cared for until their owners could reclaim them. News reports showed volunteers walking dogs and cleaning cat cages at the two locations (Chico and Oroville) where evacuees were being taken.

I have been meaning to take NVADG’s training for some time, and know several people who are regular volunteers with the group. But the fact that I had not yet been to even one of the group’s orientations meant that I needed to stay out of their territory. Instead, I brought my pups to the shelter Saturday morning – a tad more composed than the previous sleep-deprived day – and got to work. The shelter staff was frantic. The Humane Society of Silicon Valley (HSSV) arrived that morning with two large vans and dozens of crates; they took on more than 70 of our shelter residents, animals who had stayed well past their legal “stray hold” time, and had either been languishing on the adoption row for quite some time, or had not even made it to the adoption row yet. In any case, they were not animals displaced by the fire, but had been at the shelter for weeks (and even months, in some cases).

As quickly as the HSSV could load cats (lots) and dogs (a few), our kennel workers were cleaning kennels and cages and moving animals. They were trying to make room on what is usually the isolation side of the shelter for fire evacuees. The shelter will be holding the evacuated and rescued dogs indefinitely, to give their owners as much time as needed to find, identify, claim, and ultimately regain possession of their pets. Holding these pets apart from the general population of stray and unwanted dogs will help their owners look for and/or visit them, until they are able to take them “home.” I helped the kennel attendants move dogs, find bedding, fill water bowls, and take dogs out to potty.

The vast majority of the dogs who have been rescued or evacuated from the fire zone are being held at the two sites operated by the NVADG group, but they are sending all the dogs who can’t be safely held at those sites to the Northwest SPCA, including dogs who are showing (understandable) aggression to the volunteers or other dogs, trying (or managing) to escape from their wire crates, or hurt themselves in an effort to do so. The shelter’s facility is far more secure, with permanent runs and highly experienced staff. Every day, a few more big and anxious dogs are transferred from the emergency holding site to the much-stronger (and fortunately, increasingly roomy) shelter.

Volunteers from the rescue group from a town about an hour away, Ruff Pack Refuge, started showing up and looking for things to do, and I sent them to an outdoor run to play with my puppies for a while. When their leader showed up, they started busying themselves with unloading donated food, kitty litter, towels, and other supplies they had collected for the shelter, and selecting more dogs and cats to take back to their area for fostering and adoption. I went outside and gave my pups my final goodbye kisses, tears running down my cheeks, as the volunteers looked a little awkwardly away. “This is the second time I have said goodbye to them! I didn’t think I would cry this time!” I explained, but I had to leave before they started loading the pups and other animals into crates for the drive to where they will next be made available for adoption. A little weeping is one thing; I didn’t want anyone to hear me sob.

Sunday, November 11

I meant to go help the kennel attendants clean the shelter on Sunday, just to give them a bit of a break. The shelter is closed on Sundays, and that makes the day a little easier for them anyway – but it was a moot point. I just couldn’t face the shelter. I needed a day off with my dogs. We didn’t even do much – no hikes or periods of throwing the ball. The air was just thick with smoke. We spent a serious amount of time on the couch together.

Monday, November 12

Officially, my local shelter was closed on Monday, a holiday. Unofficially, there were people coming to look for their evacuated animals and people bringing donations of pet food and blankets to the shelter. I had to work for part of the day, but I stopped by the shelter, too, and helped distribute fresh bedding to the dogs in the kennels.

Over the course of the previous days, the weather forecasters were predicting high winds and a much higher fire danger; fortunately, the winds never got as strong as they had been on the first day of the fire. And finally, on Monday, they died down altogether. The good news: This lessened the fire danger. The bad news: This allowed the smoke to drift over my town and just settle like a muddy pond. The air quality is just awful. The sun looks like a copper penny; the moon looks like an actual orange slice. No stars can cut through the gloom. A new number for the death toll of the fire is announced on the news each evening; it grows higher every day, though the fire hasn’t killed anyone since the day it started. Rather, “rescue” workers keep finding the bodies of people (and many animals) who perished in the firestorm on that first day.

I looked on social media for links to “my” puppies, and had to settle for photos that the rescue had posted of them with the volunteers who had fetched them. When I asked about them via email, I was told that they would send me the links when the pups had been cleared by the group’s veterinarian.

Tuesday, November 13

My major accomplishment for the day was taking my computer and cameras back to my office, and putting my work computer system back together again. I answered some emails and checked on the progress of articles for the next issue.

That evening, I drove with my friend Sarah to an agility class she is taking about an hour away. It gave us a chance to talk about everything dog- and fire-related. The class itself was very technical, geared toward folks who are experienced and immersed in agility competition. The dogs never came out of their crates, but the participants took turns practicing the footwork for precise turns and changes of direction and playing the part of agility dogs. It was interesting and fun – and it was nice to take a break from the bad air and the nightly press conference and increase in the death toll.

As I collapsed into bed that night, I got a text from Sarah: She had been contacted by someone at NVADG who said the group needed some qualified and experienced help.

NVADG’s most highly trained volunteers were working daily in the evacuated zones where the fire had first destroyed so much; only the most qualified volunteers were allowed in such a dangerous environment to look for and rescue surviving pets. Daily, they brought more and more animals down from the wreckage of Paradise to safety.

In addition, NVADG’s regular volunteer corps was exhausted from caring for 1,365 animals – dogs, cats, rabbits, pet birds, chickens, ducks, geese and more – in two locations. All the animals are essentially living in crates for the time being, so an army of dog walkers (and cat cage cleaners) is needed to get the dogs out several times a day for relief. Many also require medical attention. Sarah asked me if I could join her and some of her staff members to help out at one of the animal evacuation sites in the morning, and I was more than happy to say I would.

I won’t say that the regular NVADG rules regarding the use of only volunteers who have been through the group’s training program are getting broken, just that the organization is about to gain some more very qualified and experienced volunteers who will undoubtedly go through the organization’s next training event when it’s offered – and in the meantime, the group will get some relief. I’m super happy to be able to go put my hands on dogs (and cats!) from the evacuation zone, and to be of more use.

I’ll let you know how those efforts go in a future post.

As of this writing, the human death toll from the Camp Fire stands at 56; the number of animals who lost their lives is incalculable. Over 52,000 people are still displaced from their homes by the still-burning fire, and 8,650 homes are confirmed destroyed. My heart goes out to all of those who have lost loved ones and/or their homes, and my deep admiration goes to all of those who are still working to make each day a little more comfortable for the evacuees.

If you are so moved, please consider a donation to one of these really terrific organizations:

North Valley Animal Disaster Group (help for animal victims of the fire)

North Valley Community Foundation (help for human victims of the fire)