Lymphoma accounts for 7 to 24% of all canine cancers and approximately 85% of all the blood-based malignancies that occur, making it one of the most common cancers found in dogs. Lymphoma – also referred to as lymphosarcoma – is not a singular type of cancer but rather a category of systemic cancers with over 30 described types.

Lymphoma occurs when there is a genetic mutation or series of mutations within a lymphocyte that causes the cells to grow abnormally and become malignant, ultimately affecting organs and body functions. Lymphocytes are the infection-fighting white blood cells of the immune system and are produced by the lymphoid stem cells in the bone marrow and lymphoid tissue in the bowel. Their role is to prevent the spread of disease, to provide long term immunity against viruses, aid in wound healing, and provide surveillance against tumors.

Lymphocytes are part of the lymphatic system – a network of tissues and organs that help rid the body of toxins, waste, and other unwanted materials. The primary function of the lymphatic system is to transport lymph, a fluid containing lymphocytes, throughout the body. Unfortunately, cancerous lymphocytes circulate through the body just as the normal lymphocytes do.

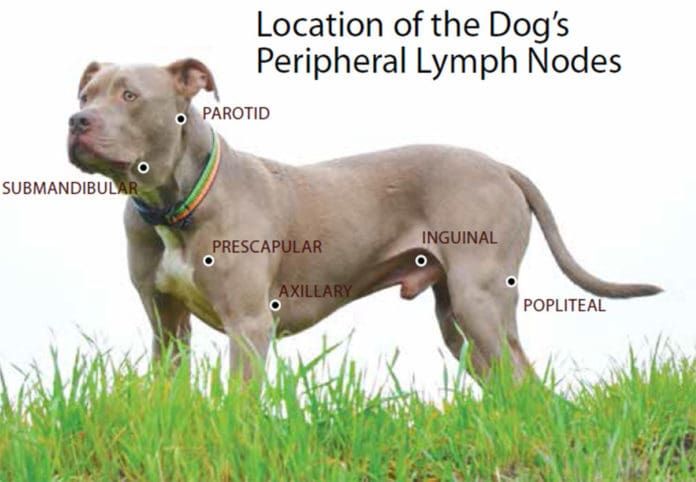

Although lymphoma can affect virtually any organ in the body, it most commonly becomes evident in organs that function as part of the immune system – the locations where lymphocytes are found in high concentrations – such as the lymph nodes, spleen, thymus, and bone marrow. Swelling occurs when the numbers of cancerous lymphocytes increase; one of the most common sites of accumulation are in the lymph nodes themselves, resulting in an increased size of these structures.

[post-sticky note-id=’377229′]

Canine lymphomas are similar in many ways to the non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas (NHL) which occur in humans, though dogs are two to five times more likely than people to develop lymphoma. The two diseases are so similar that almost the same chemotherapy protocols are used to treat both, with similar responses reported. NHL has been featured recently in the high-profile cases involving individuals who developed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma after using the weed killer glyphosate (most highly recognized under its best-selling brand name, Roundup).

Because of its similarity to the human form, canine lymphoma is one of the best understood and well-researched cancers in dogs. It is one of the few cancers that can have long periods of remission, even lasting years, and although rare, complete remission has been known to occur.

CAUSE

The cause of canine lymphoma is not known. It is suspected that the cause may be multifactorial. In an effort to determine what factors affect the possibility of developing the disease, researchers are looking at the role of environmental components such as exposure to paints, solvents, pesticides, herbicides, and insecticides; exposure to radiation or electromagnetic fields; the influence of viruses, bacteria, and immunosuppression; and genetics and chromosomal factors (changes in the normal structure of chromosomes has been reported). It is thought that dogs living in industrial areas could be at a higher risk for developing lymphoma.

BREED DISPOSITION AND RISK FACTORS

Although the direct cause of lymphoma cannot be identified, studies have found that there are certain breeds that are at higher risk of developing the disease. The most commonly affected breed is the Golden Retriever, equally represented by B-cell and T-cell lymphomas (see below).

Other breeds showing increased incidence include the Airedale, Basset Hound, Beagle, Boxer, Bulldog, Bull Mastiff, Chow Chow, German Shepherd Dog, Poodle, Rottweiler, Saint Bernard, and Scottish Terrier. Dachshunds and Pomeranians have been reported as having a decreased risk of developing canine lymphoma.

Lymphoma can affect dogs of any breed or age, but it generally affects middle-aged or older dogs (with a median age of 6 to 9 years). There has been no gender predisposition noted, but there are reports that spayed females may have a better prognosis.

A recent large scale study published in the Journal of Internal Veterinary Medicine (Volume 32, Issue 6, November/December 2018) and conducted by the University of Sydney School of Veterinary Science in Australia, examined veterinary records for breed, gender, and neuter status as risk factors for developing lymphoma. A number of breeds were observed to be at risk that had not been previously identified as being in that category.

The study also demonstrated the opposite: Several breeds previously documented to have an increased risk of lymphoma failed to show an increased risk. Additionally, the study found males had a higher risk overall across breeds, as did both males and females that had been neutered or spayed. Mixed breeds generally had a decreased risk when compared with purebred dogs. While these findings may be inconsistent with other generally accepted risk factors, the study states, “These three factors need to be considered when evaluating lymphoma risk and can be used to plan studies to identify the underlying etiology of these diseases.”

LYMPHOMA TYPES AND SYMPTOMS

Typically, a dog who gets diagnosed with lymphoma will initially be taken to a veterinarian because one or more lumps have been found under the neck, around the shoulders, or behind the knee. These lumps turn out to be swollen lymph nodes. The majority of dogs (60 to 80%) do not show any other symptoms and generally feel well at the time of diagnosis.

Advanced symptoms depend on the type of lymphoma and the stage and can include swelling/edema of the extremities and face (occurs when swollen lymph nodes blocks drainage), loss of appetite, weight loss, lethargy, excessive thirst and urination, rashes, and other skin conditions. Breathing or digestive issues may be present if the lymph nodes in the chest or abdomen are affected.

Because the lymphatic system aids in fighting infection, fevers are often one of the first indicators of the disease. Additionally, since lymphoma affects and weakens the immune system, dogs may be more susceptible to illnesses, which can lead to complicated health issues. Lymphoma itself, however, is not thought to be painful to dogs.

Lymphoma can occur anywhere in the body where lymph tissue resides and is classified by the anatomic area affected. The four most common types are multicentric, alimentary, mediastinal, and extranodal. Each type has its own set of characteristics that determine the clinical signs and symptoms, rate of progression, treatment options, and prognosis. Furthermore, there are more than 30 different subtypes of canine lymphoma.

- Multicentric Lymphoma. This is the most predominant type of lymphoma, accounting for 80 to 85% of all canine cases. It is similar to non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma in humans. The first noticeable sign of this form is usually enlargement of the lymph nodes in the dog’s neck, chest, or behind the knees, sometimes up to 10 times their normal size, with the patient not showing any other distinctive signs of illness.

Multicentric lymphoma tends to have a rapid onset and affects the external lymph nodes and immune system; involvement of the spleen, liver, and bone marrow are also common. The disease may or may not involve other organs at the time of diagnosis, but it eventually tends to infiltrate other organs, causing dysfunction and eventually leading to organ failure.

As it progresses, additional symptoms including lethargy, weakness, dehydration, inappetence, weight loss, difficulty breathing, fever, anemia, sepsis, and depression may be observed. This form can also metastasize into central nervous system (CNS) lymphoma in later stages, which can cause seizures and/or paralysis.

- Alimentary (Gastrointestinal) Lymphoma. This is the second most prevalent form of canine lymphoma, however it is much less common, accounting for only about 10% of lymphoma cases.

Because it is in the digestive tract, it is more difficult to diagnose than the multicentric form. It is reported to be more common in male dogs than females. This type forms intestinal lesions, typically resulting in the manifestation of gastrointestinal-related signs, including excessive urinating or thirst, anorexia, abdominal pain, vomiting, diarrhea (dark in color), and weight loss due to malabsorption and maldigestion of nutrients.

The disease affects the small or large intestine, and it has the potential to restrict or block the passage of the bowels, resulting in serious and complicated health risks or fatality.

- Mediastinal Lymphoma. This is the third most common type of canine lymphoma, but it is still a fairly rare form. Malignant lesions develop in the lymphoid tissues of a dog’s chest, primarily around the cardiothoracic region. This form is characterized by enlargement of the mediastinal lymph nodes and/or the thymus. The thymus serves as the central organ for maturing T lymphocytes; as a result, many mediastinal lymphomas are a malignancy of T lymphocytes.

The symptoms of mediastinal lymphoma tend to be fairly apparent, involving enlargement of the cranial mediastinal lymph nodes, thymus, or both. It can also cause swelling and abnormal growth of the head, neck, and front legs.

Dogs manifesting with this disease may have respiratory problems, such as difficulty breathing or coughing and swelling of the front legs or face. Increased thirst resulting in increased urination can also occur; if it does, hypercalcemia (life-threatening metabolic disorder) should be tested for as it seen in 40% of dogs with mediastinal lymphoma.

- Extranodal Lymphoma. This is the rarest form of canine lymphoma. “Extranodal” refers to how it manifests in a location in the body other than in the lymph nodes. Organs typically affected by this type include eyes, kidneys, lungs, skin (cutaneous lymphoma), and central nervous system; other areas that can be invaded include the mammary tissue, liver, bones, and mouth.

Symptoms of extranodal lymphoma will vary greatly depending on which organ is impacted; for example, blindness can occur if the disease is in the eyes; renal failure if in the kidneys, seizures if in the central nervous system, bone fractures if in the bones, and respiratory issues if in the lungs.

The most common form of extranodal lymphoma is cutaneous (skin) lymphoma, which is categorized as either epitheliotropic (malignancy of T lymphocytes) or nonepitheliotropic (malignancy of B lymphocytes.) In the early stages, it usually presents as a skin rash with dry, red, itchy bumps or solitary or generalized scaly lesions and is fairly noticeable as the condition causes discomfort.

Because of this presentation, it is sometimes initially mistaken for allergies or fungal infections. As it becomes more severe, the skin will become redder, thickened, ulcerated, and might ooze fluids; large masses or tumors can develop. Cutaneous lymphoma can also affect the oral cavity causing ulcers, lesions, and nodules on the gums, lips, and roof of the mouth (sometimes mistaken at first as periodontal disease or gingivitis).

SUBTYPES

Within each of the four types described above, the disease can be categorized further into subtypes. There are more than 30 different histologic subtypes of canine lymphoma identified; some researchers theorize that there may be hundreds of subtypes, based on molecular analysis of markers, classifications, and subtypes of lymphocytes.

At the moment, further knowledge about the various subtypes would probably not result in significant changes in treatment protocols. In the future, targeted therapies for subtypes could lead to more effective treatments and improved prognosis.

The two primary and especially relevant subtypes are B-cell lymphoma and T-cell lymphoma. Approximately 60 to 80% of lymphoma cases are of the B-cell lymphoma subtype, which is a positive predictor; dogs with B-cell lymphoma tend to respond positively to treatment with a higher rate of complete remission, longer remission times, and increased survival times. T-cell lymphoma constitutes about 10 to 40% of lymphoma cases and has a negative predictive value based on not responding as well to treatment and for being at a higher risk for hypercalcemia.

DIAGNOSING CANINE LYMPHOMA

Early detection and treatment are essential to ensuring the best possible outcome for lymphoma cases. Because dogs generally feel well and there are often only swollen lymph nodes (with no pain exhibited) as a symptom, catching the disease early can sometimes be quite difficult. As a result, the cancer can be quite advanced by the time a diagnosis is made. (Lymphoma is not the only the disease that creates swollen lymph nodes; this symptom does not guarantee your dog has lymphoma.)

Because multicentric lymphoma accounts for the majority of cases, an aspirate of an enlarged peripheral lymph node is usually sufficient to reach a presumptive diagnosis of the most common types of lymphomas.

Although diagnosis from cytology is fairly easily obtained, it does not differentiate the immunophenotype (B versus T lymphocyte). Histopathologic tissue evaluation (biopsy) is required in order to identify the type with the process of immunophenotyping.

Immunophenotyping is a molecular test usually performed by flow cytometry (a sophisticated laser technology that measures the amount of DNA in cancer cells) that classifies lymphomas by determining if the malignancy originates from B lymphocytes or T lymphocytes. Determining whether a lymphoma is B-cell or T-cell is invaluable as it provides the best predictive value; the adage “B is better, T is terrible” reflects this in its simplest form.

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common histologic subtype of lymphoma occurring in dogs. Most intermediate to high grade lymphomas are B-cell lymphomas – they tend to respond better and longer to chemotherapy than T-cell lymphomas; however, dogs with T-cell lymphoma have been known to go into remission for several months.

Another phenotyping test, the PCR antigen receptor rearrangement (PARR), can determine whether the cells are indicative of cancer or more consistent with a reactive process. For example, because the lymph nodes in the area of the jaw are reactive, the PARR test can help determine if cancer is present or if the dog just badly needs his teeth cleaned. The PARR test can also be used to detect minimal residual disease. Research is continuing to determine if this will be a useful clinical marker of early recurrence.

To ascertain the patient’s overall health, a complete physical exam will be performed; additional diagnostics often include a blood chemistry panel, urinalysis, x-rays, ultrasounds, and other forms of diagnostic imaging (these tests are also used for staging the disease).

In particular, it is important to screen for hypercalcemia. Hypercalcemia is a condition in which the hormone PTHrP (parathyroid hormone-related peptide) creates dangerous elevations in the blood calcium level. This well-documented syndrome is associated with lymphoma in dogs and is most often seen in T-cell lymphomas.

About 15% of dogs with lymphoma overall will have elevated blood calcium levels at diagnosis; this increases to 40% in dogs who have T-cell lymphoma. The condition causes additional clinical signs including increased thirst and urination, and, if left untreated, can cause serious damage to the kidneys and other organs and be life-threatening.

Unfortunately, due to the rapidly progressive nature of lymphoma, decisions regarding treatment need to be made as soon as possible after diagnosis. Unlike most other forms of cancer, lymphoma requires urgent care; without treatment, the median survival time is one month after diagnosis. Therefore, owners should be prepared to start treatment on the day of diagnosis, or within a day or two at most.

STAGING

Once a diagnosis of lymphoma has been made, the stage (extent) of the lymphoid malignancy should be determined, and to assess this, several tests are recommended: lymph node aspirate, complete blood count, chemistry panel, urinalysis, phenotype, thoracic and chest radiographs, abdominal ultrasound, and a bone marrow aspirate.

Staging is prognostically significant; in general, the more extensive the spread, the higher the stage, the poorer the prognosis. However, even dogs with advanced disease can be successfully treated and experience remission. These tests also provide information about other conditions that may affect treatment or prognosis. The World Health Organization (WHO) five-tier staging system is the standard used to stage lymphoma in dogs:

- Stage I: Single lymph node is involved.

- Stage II: Multiple lymph nodes within in the same region are affected.

- Stage III: Multiple lymph nodes in multiple regions involved.

- Stage IV: Involvement of liver and/or spleen (in most cases lymph nodes are affected but it is possible that no lymph nodes are involved).

- Stage V: Bone marrow or blood involvement, regardless of other areas affected and/or other organs other than liver, spleen and lymph nodes affected.

In addition, there are two categories of clinical substages. Dogs are categorized with substage A if clinical signs related to the disease are absent, and categorized as substage B if clinical signs related to the disease are present (systemic signs of illness).

TREATMENT

Although canine lymphoma is a complex and challenging cancer, it is one of the most highly treatable cancers and most dogs respond to treatment. In fact, many dogs with lymphoma outlive animals with other diseases such as kidney, heart, and liver disease. While lymphoma is not curable, the goal with treatment is to quickly achieve remission for the longest period possible thus giving dogs and their owners more quality time together. It is essential that the type of lymphoma is identified as the type impacts treatment and prognosis. And because lymphoma is a very aggressive cancer, it is important to begin treatment as soon as possible.

Since lymphoma is a systemic disease that affects the whole body, the most effective treatment is also systemic in the form of chemotherapy, which provides many dogs with prolonged survival times and excellent quality of life, with little or no side effects.

The specific type of chemotherapy treatment used will vary based on the type of lymphoma. Other factors to consider when choosing a protocol are the disease-free interval, survival time, typical duration of remission, scheduling, and expense. Again, dogs with B-cell lymphoma tend to respond much more favorably to treatment than those with T-cell.

Because lymphoma is so common in dogs, there has been a substantial amount of research and testing of many different combinations of chemotherapy treatments. Multiagent chemotherapy protocols are considered the gold standard of treatment and have shown to provide the best response in terms of length of disease control and survival rates, as compared to single agent protocols.

The Madison Wisconsin Protocol, also known as UW-25 or CHOP, is a cocktail of drugs modeled after human lymphoma treatments and is widely considered to be the most effective treatment for intermediate- to high-grade canine lymphomas. This protocol utilizes three cytotoxic chemotherapy drugs – cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin (hydroxydaunrubicin), and vincristine (brand name Oncovin) – in combination with prednisone (CHOP). The prednisone is typically given daily at home as a tablet with the remainder of the protocol agents administered by an oncology specialist.

On average, 70 to 90% of dogs treated with CHOP experience partial or complete remission. For dogs with B-cell lymphomas, 80 to 90% can be expected to achieve remission within the first month. The median survival time is 12 months with 25% of patients still alive at two years. For T-cell lymphoma, about 70% will achieve remission with an average of six to eight months survival.

Other treatment options include the COP chemotherapy protocol (cyclophosphamide, Oncovin [vincristine], and prednisone), vincristine and Cytoxan; single-agent doxorubicin; and and lomustine/CCNU. As a primary treatment, single-agent doxorubicin can result in a complete remission in up to 75% of patients with median survival time of up to eight months, though cumulative treatment with doxorubicin may result in cardiotoxicity, so the protocol may be contraindicated in any dog with evidence of or a history of pre-existing heart disease. Lomustine/CCNU is reported to be the most effective treatment for cutaneous lymphoma.

REMISSION

Remission is the condition in which the cancer has regressed. Partial remission means that the overall evidence of cancer has been reduced by at least 50%; complete remission indicates that the cancer has become undetectable to any readily available diagnostic screening (but it does not mean that the lymphoma has left the dog’s body, only that it has been treated into dormancy).

A dog in remission is essentially indistinguishable from a cancer-free dog. The lymph nodes will return to normal size and any illness related to the cancer usually resolves. Overall, there is approximately a 60 to 75% chance of achieving remission regardless of the protocol selected.

Studies show that the average time for a dog to be in remission the first time is eight to 10 months, including the period of chemotherapy administration. Remission status is continually monitored; for dogs with enlarged lymph nodes it typically involves checking the size of the lymph nodes. For dogs with other types of lymphoma, periodic imaging may be recommended. The Lymphoma Blood Test (LBT) from Avacta Animal Health can also be used monitor status since LBT levels can increase less than eight weeks before relapse.

Unfortunately, remission eventually relapses in most cases, but many dogs can restart chemotherapy with the hope of regaining remission status. At times, the same chemotherapy protocol may be used. For dogs successfully treated initially with the CHOP protocol, restarting CHOP at the time of the first relapse is typically recommended. About 90% of those treated with a second CHOP protocol will achieve another complete remission, however, the duration is usually shorter than the first time.

If a patient does not respond to the first CHOP protocol before completion or the treatment fails during the second protocol, the use of rescue protocols can be attempted; these consist of drugs that are not found in the standard chemotherapy protocols and kept in reserve for later use.

Commonly used rescue protocols include LAP (L-asparaginase, lomustine/CCNU, and prednisone) and MOPP (mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine and prednisone). These are less likely to result in complete remission and some dogs will only achieve a partial remission, with an overall response rate of about 40 to 50%, and a median survival rate of 1.5 to 2.5 months.

Because cancer cells evolve over time, the disease can become resistant to certain drugs. Further treatments can be given, but it can become more difficult to achieve remission a second or third time and there does not appear to be any substantial effect on survival times.

OTHER TREATMENT OPTIONS

Here are some compelling alternatives to consider in addition to the standard protocols described above:

- Prednisone. This is usually a component of most lymphoma treatment protocols because it actually destroys lymphoma cells. It can even be administered as a standalone treatment. The average survival time without chemotherapy is about one month but treating with prednisone alone can increase this to about two to three months, with an average of 50% responding.

- Tanovea-CA1 (rabacfosadine). This is a promising new advancement in treating canine lymphoma. This drug has been conditionally approved for use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), pending a full demonstration of its effectiveness (additional field studies are currently taking place to obtain full approval).

[post-sticky note-id=’377235′]

Tanovea-CA1 is designed to target and destroy malignant lymphocytes and can be used not only to treat dogs that have never received any treatment but also those no longer responding to chemotherapy. It has demonstrated a 77% overall response and a 45% complete response rate. It is administered by veterinarians in five treatments every three weeks via intravenous infusion and is shown it to be generally well-tolerated.

- Bone Marrow Transplant. One of the newest approaches to treating canine lymphoma is the bone marrow transplant – a form of stem cell therapy – modeled after a method used in human medicine. The process involves the dog receiving and completing CHOP therapy (which puts the cancer in remission); the harvesting and preservation of healthy stem cells from the patient; the administration of radiation to destroy any remaining cancer cells; and the returning of healthy cells to repopulate and restore blood cells.

In humans, the cure rate is about 40 to 60%; the procedure has been determined to be safe for use in dogs with cure rates of 33% for B-cell lymphomas and 15% for T-cell lymphomas. The process is expensive ($19,000 to $25,000) and requires about two weeks of hospitalization. Currently there are only two locations in the U.S. offering the procedure: the North Carolina State College of Veterinary Medicine (in Raleigh) and Bellingham (Washington) Veterinary Critical Care.

At some point lymphomas become resistant to treatment and no further remissions can be obtained. Eventually the uncontrolled cancer will infiltrate an organ (often the bone marrow or the liver) to such an extent that the organ fails. Under those circumstances, it is best to focus on high quality of life for the longest possible survival time.

PROGNOSIS

Like most cancers, the eventual prognosis for dogs with lymphoma isn’t very uplifting. But it is a very treatable cancer, and dogs live well and longer with treatment. Several prognostic factors have been identified for estimating a dog’s response to treatment and survival time:

- Dogs with signs of systemic illness (substage B) tend to have a worse prognosis than dogs with substage A.

- Dogs with lymphoma histologically classified as being either intermediate- or high-grade tend to be highly responsive to chemotherapy, but early relapse is common with shorter survival times.

- Dogs with lymphoma histologically classified as being low-grade have a lower response rate to systemic chemotherapy yet experience a positive survival length advantage when compared to intermediate- or high-grade tumors.

- Dogs with T-cell lymphomas have a shorter survival time when compared with dogs with B-cell based malignancies.

- Dogs with diffuse alimentary, central nervous system, or cutaneous lymphoma tend to have shorter survival times when compared to dogs with other anatomic forms of lymphoma.

- Presence of hypercalcemia or anemia or a mediastinal mass are all associated with a poorer prognosis.

- Intestinal lymphoma has a very poor prognosis.

- Expectations for cases with Stage V lymphoma are much lower than those assigned to Stages I to IV.

- Prolonged pre-treatment with corticosteroids is often a negative prognostic factor.

- Ultimately, the estimates for survival times depend on the type of lymphoma combined with the stage and the treatment option selected (if any).

- In the absence of treatment, most of the dogs diagnosed with lymphoma succumb to the disease in four to six weeks.

- The median survival time with a multi-agent chemotherapy protocol is 13 to 14 months.

- Traditional chemotherapy results in total remission in approximately 60 to 90% of cases with a median survival time of six to 12 months.

- In about 20 to 25% cases, dogs live two years or longer after initiation of standard chemotherapy treatment.

- Dogs treated with rescue protocols have a survival rate of 1.5 to 2.5 months.

- Studies indicate that dogs who underwent splenectomy show a median survival rate of 14 months.

- Complete cure is rare, but not unheard of. Bone marrow transplants show promise and potential for increased cure rates.

Above all, remember that prognoses are only guidelines based on average accumulative experiences. They are numbers, and as a dear friend and veterinary oncologist has said to me many times, “Treat the dog, not the numbers.”

![scout2[1]](https://www.whole-dog-journal.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/scout21-696x520.jpg.optimal.jpg)

starting with a favorite toy. Rub the toy on the paper towel, and start back at Step 1, placing the toy in plain view and move quickly through to Step 5.

starting with a favorite toy. Rub the toy on the paper towel, and start back at Step 1, placing the toy in plain view and move quickly through to Step 5.