By Randy Kidd, DVM, PhD What’s on your dog’s mind? You may never know, but it can be helpful to know at least a little something about his brain – and the rest of his central nervous system (CNS). The CNS describes the system of neurons formed by the spinal cord, brain stem, cerebellum, and cerebrum. This month’s installment of the Tour of the Dog focuses on the CNS, its diseases and disorders, and treatments for those ailments. The peripheral nervous system (PNS), comprised of the cranial and spinal nerves (specialized nerves that carry information to the brain stem or spinal cord), are beyond the scope of this article. Macroanatomy

342

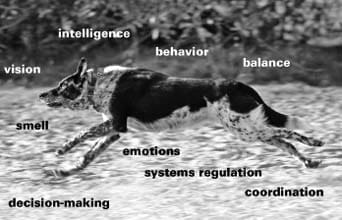

The CNS “organ system” includes nerve cells (neurons) as well as tissues and cells that support the function and health of the nerve cells. The brain itself lies within a protected vault, encased by the protective “headgear” of the cranial bones. Extending backward from the brain is the brain stem, and continuing on from this stem is the spinal cord. The spinal cord extends inside the protective coverings of the spinal vertebrae to just beyond the bones of the pelvis, providing branching motor and sensory nerves to the limbs and organ systems along the way. A connective tissue called the meninges acts as a protective outer membrane surrounding the CNS tissues. It’s actually a collection of three layered membranes: the dura, arachnoid, and pia maters. The outer, dura mater (literally, tough mother) is a tough and fibrous outer covering. Internal to the dura is a thin meninge called the arachnoid mater, and its cobweblike structure (thus the term arachnoid, or spider) unites the dura with the pia mater. The pia mater is a thin and highly vascular membrane adhering closely to the surface of the brain. Note: When we consider the moving animal, it is important to appreciate that the meninges extend from the fibrous capsule they form around the brain, backward along the length of the spinal cord. The meninges thus offer a resilient membrane that gives elastic support to the flexing, contracting, rotating spine. In addition, since it is continuous, whenever a spinal vertebra is “stuck,” that “stuckage” will be reflected at other point(s) along the spine. This means that a chiropractic adjustment necessary in the lumbar region, say, probably will also necessitate additional adjustments somewhere else along the spine – say, in the neck region. Cerebral spinal fluid (CSF), produced by large ventricles that lie within the inner part of the brain, circulates in the subarachnoid space. The CSF helps maintain a constant environment for the neurons and glia by transporting metabolites from the blood and removing by-products of brain metabolism. It also helps connect the brain to rest of the body’s immune system, and creates a fluid cushion for the brain to float in. A sample of CSF fluid can be collected and examined as a diagnostic aid. Slice into the main part of the brain and you will see that most of its innards are white, with a thin outer layer, the cerebral cortex, that fits over the white matter like a glove. The cerebral cortex (cortex is Latin for “bark”) is extensively folded, which allows for much more surface area than would be available on a flattened surface. This increased surface area makes room for more cells; theoretically, the more intensely folded the cortex, the smarter the animal. The brain is physically divided into a left and right hemisphere, and the hemispheres are connected at their base by a horn-shaped structure called the hippocampus. For many years it was thought that the functions of the left brain (the logical, linear, focused-thinking brain) and right brain (emotional, global-thinking) were entirely separated, and each hemisphere was solely responsible for its designated function. Today’s research, however, indicates that there are many more connections and cross-overs between the hemispheres than originally thought. Thus, even when a human is engaged in linear, logical thought, the emotional brain is always tuned in, meaning that even the most logical of thoughts are being processed, at least to some extent, in an emotional fashion. Realizing this to be true, recent brain science has led to an extended appreciation of the mind/body connection. Archeology of the brain The brain has evolved over eons, with certain anatomical parts (and thus certain functional capacities) of the brain developing more in some animals than in others. The brainstem is the oldest part of the brain. It evolved more than 500 million years ago, and because it resembles the entire brain of a reptile, it is often referred to as the reptilian brain. It determines the general level of alertness and warns the organism of important incoming information, and handles basic bodily functions necessary for survival, breathing and heart rate, as examples. The cerebellum is attached to the rear of the brainstem. Among other functions, the cerebellum maintains and adjusts posture and coordinates muscular movement. Memories for simple learned responses may also be stored here. The limbic system is the group of cellular structures located between the brainstem and cortex. Two key parts of the system are the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. Although it is only about the size of a small pea, the hypothalamus regulates eating, drinking, sleeping, waking, body temperature, balance, and many other functions. It also directs the pituitary gland, the gland many consider the “master gland” of the body. The limbic system evolved sometime between 200 and 300 million years ago. Because it is most highly developed in mammals, it is often called the mammalian brain. In addition to its other functions, the limbic system is involved in the emotional reactions that have to do with survival. The cerebrum is the largest part of the dog’s (and other mammals’) brain. It is divided into two halves, or hemispheres, each of which controls its opposite half of the body. The hemispheres are connected by a band of nerve fibers, called the corpus callosum. The corpus callosum is the largest fiber pathway in the brain – a “bridge” of several hundred million nerve fibers. Covering each hemisphere is a thin layer of intricately folded nerve cells called the cerebral cortex. The cortex is the area of the brain where we and our dogs are able to remember, communicate, understand, and create. The cerebrum’s cortex first appeared in mammals about 200 million years ago. It is the part of the brain that is more highly developed in the human species than in any other animal. The cerebral cortex is further divided into several lobes, each with its own function. (“Mapping” of the brain is an ongoing process, and most of the work has been done in humans using a variety of electrical-, chemical-, and heat-based ways to analyze areas that are active during the time that specific activities or thoughts are being undertaken by the experimental subject.) The frontal lobe is primarily involved in decision-making and purposeful behavior. The parietal lobe, located just behind the frontal lobe, represents the body and its actions. The temporal lobe lies beneath parts of the parietal and frontal lobe; some of its functions include processing of auditory sounds, perception, and memory. The occipital lobe lies behind and beneath the parietal lobe and just above the cerebellum; its function is concerned with vision. Note that the importance of understanding at least some of the functions of the various brain parts is that it makes it easier to localize a lesion if one occurs. Microanatomy of the CNS Neurons are the cells that conduct nerve impulses. They are responsible for relaying sensory input (such as pain, pleasure, and the senses of smell, hearing, seeing, etc.); for proprioception (knowing where the body parts are at any time); and for transmitting impulses to the muscles to incite them to action. However, about 90 percent of the cells of the CNS are termed glial cells (meaning glue). There are several types of glial cells, each with its own function. Astrocytes and microglia provide physical and nutritional support for neurons; oligodendroglia and Schwann cells provide insulation to neurons; and satellite cells offer physical support for neurons. The brain, like the rest of the body, bathes in a soup of biochemicals that, when activated, create a variety of reactions that are essential for life. Neurons function by moving electrical impulses from one area of the body to another, and the chemicals responsible for this movement across nerve connections (synapses) are called neurotransmitters. Included in this category are epinephrine, norepinephrine, serotonin, histamine, and glutamate. Each of these is a protein that requires certain amino acids for its production; each has its specific function, and many have a specific target organ in which the function occurs. Recent evidence demonstrates that the health of neurotransmitters can be enhanced in several ways: good balanced nutrition, exercise, hand-to-fur contact such as massage, and living in a household full of love. The neurological exam Indicators for the possibility of neurological disease include behavioral changes, seizures, tremors, stumbling, or paresis or paralysis of one or more limbs. A complete neurological exam can be an extensive (and expensive) process, and, in the end, the diagnosis often resorts to simple deductive reasoning to narrow a large list of possibilities to a smaller list of more probable causes. Information about the time of onset, the course, and the duration of the complaint can be helpful. Congenital and familial disorders are most common in purebred animals at birth or within the first few years of life. Inflammatory, metabolic, toxic, and nutritional disorders can occur in any species, breed, or age. They tend to have a rapid onset and are usually progressive. Traumatic and vascular injuries have an acute onset, and they rarely become worse after the first 24 hours. Most degenerative and neoplastic disorders occur in older dogs; they tend to have a slow and gradual onset, and the symptoms often become worse over time. A complete physical may reveal nerve-related conditions. For example, a generalized bacterial infection may extend into the brain, meninges, or spinal cord; tumors may originate in one organ system and metastasize to nervous tissues; chronic inflammatory diseases may reside in organ systems, including nervous tissues; and metabolic problems that affect nerves also usually affect other organ systems. A neurologic exam should include an examination of the head, neck, thorax and thoracic limbs, lumbar and pelvic areas, pelvic limbs, anus and urethral sphincter, tail, and the animal’s gaits. Often, a veterinary chiropractor can thoroughly evaluate these areas, and, while the evaluation is in process, adjust the joints that feel “stuck” back into their normal range of motion. If the neurological deficiency is localized, the site of the lesion along the spine (or in the limb) may be evident. For example, a front limb dysfunction may be due to a lesion along the spine anywhere from the first cervical vertebra to one of the first two thoracic vertebrae. Or it may be caused by a lesion somewhere along the length of the limb, including the paws and toes. In addition to evaluating the dog’s posture and gaits (walking, trotting, turning, backing, etc.), there are many specific neurologic tests that are designed to evaluate isolated parts of the nervous system. Further tests may also be helpful. Clinical pathology may reveal a generalized infection, liver or kidney dysfunction, or hormonal or metabolic conditions that also affect the nervous tissues. Blood test results may reveal the presence of certain toxins that have caused a problem. For example, a particularly low level of serum cholinesterase suggests acute organophosphate (a common ingredient in anti-flea and tick products) toxicity. An evaluation of the cerebrospinal fluid may be helpful, especially for infections or inflammation. Radiographs can be used to detect fractures and some tumors. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be used to detect smaller lesions. An electroencephalogram (EEG) records the electrical activity of the cerebral cortex, and it is a good aid for detecting hydrocephalus, meningoencephalitis, head trauma, and cerebral neoplasia. Interestingly, the EEG is not especially proficient at diagnosing many of the more common forms of epilepsy. Diseases of the brain As you’d expect when dealing with an organ system that has a variety of cell types and a multitude of functions, there are many diseases and causes of diseases of the CNS, making diagnosis a real challenge. Almost every part of the CNS can be affected by any number of disease processes: congenital or familial, nutritional, metabolic, infectious or inflammatory, toxic, traumatic, vascular, parasitic, neoplastic, immunological, degenerative … or iatrogenic (resulting from the activity of the health practitioner) or idiopathic (of unknown origin). A diagnostic approach for any potential disease of the nervous system will entail a multidimensional approach. Often, an accurate diagnosis will depend on correlating several factors into one final picture.

288

A clinical evaluation will assess the totality of clinical symptoms. Are the symptoms diffuse or focal; symmetric or asymmetric; painful or nonpainful; progressive, regressive, or static; mild, moderate, or severe? An anatomic location of the lesion may be evident from the prevailing signs. Potential mechanisms of the disease are considered (from the entire list above), and hopefully a short list of the most likely possibilities can be generated. Congenital disorders are most common in purebred animals at birth or shortly thereafter. Some familial disorders cause a progressive degeneration of neurons in the first year of life, while others (such as inherited epilepsy) may not manifest for several years. Trauma is a major cause of neurologic dysfunction due to physical damage, hemorrhage, edema, and progressive formation of oxygen-containing free radicals. Traumatic conditions have a rapid onset of symptoms, and the damage is generally complete within 24 to 48 hours. In other words, clinical signs will usually not get worse than they are one or two days after the traumatic event; whether the signs gradually improve depends on the extent of the original damage and the success of the treatment given. Infections (meningitis – infection of the meninges, and encephalitis – infection of the brain) can be caused by any of many agents including bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, prions (a minute particle of a virus), and algae. Rabies and canine distemper are two examples of viral diseases that have a serious nervous system component. The most common neurological toxicities in dogs are caused by insecticides (such as those found in many flea and tick products), but the list of neurotoxins in the environment is almost endless. Metabolic alterations that result in nervous signs include hypoglycemia, hepatic dysfunction, uremia (kidney failure), and alterations in mineral metabolism. Both hypo- and hyperthyroidism can cause neurological signs, as can hypoadrenocorticism (Addison’s disease) or hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s disease). Vitamin deficiencies can cause ataxia, stupor, coma, and/or seizures. Vascular lesions are usually due to septicemia or bacterial embolism within the CNS. Unlike their human counterparts where cerebrovascular disease from arteriosclerosis (thickening and loss of elasticity of the arterial walls) and hypertension (high blood pressure) are fairly common, these two are rare diseases in dogs. Nervous system neoplasias (tumors) are reported more often in dogs than in other domesticated species. Overall frequency of tumors reported varies considerably, depending on the survey – from almost 3 percent of all dogs examined at necropsy to less than 0.02 percent of the examined dogs. One survey found that the most common sites for neoplasia in young dogs were located in the hematopoietic (blood forming) system, the brain, and the skin. Brachy-cephalic breeds – such as Boxers, English Bulldogs, and Boston Terriers – are at increased risk for developing certain tumors of the brain tissues. Each and every one of the many cell types present in the CNS can be altered to grow into its own tumor types – for example astrocytes, oligodendrocytes, and glial cells, respectively producing astrocytomas, oligodendrogliomas, and gliomas. Furthermore, each tumor type has its own propensity for growth or its ability to spread and become malignant. It is therefore an extreme challenge to accurately diagnose nerve tissue tumors and to offer a prognosis for how they will perform in the future. Holistic approach Given the difficulty of accurately diagnosing and adequately treating a disease of the nervous system, it is important that we think in terms of prevention of CNS disorders rather than cure. And while the CNS is all-inclusive in terms of its impact on the whole body, there are some general ways to help your dog maintain a healthy CNS. • At the top of the list is exercise. In the case of the CNS, we are referring to whole body/mind/spirit and heart exercise. Daily, moderate exercise will bathe all the body’s nerves with health-sustaining nutrients, and activity helps to keep all systems in balance. But the nervous system also needs to have its thinking, reasoning, creativity “worked” on a daily basis. Dogs (and people) who are exposed to novel experiences and whose day-to-day activities require creative reasoning are able to maintain healthier brains well into old age. Take your dog for a walk, meet new people and other animals, continue basic training and add “tricks” that stimulate the brain – all good prescriptions for a healthy brain. • Nutrition. While good nutrition is absolutely essential for a healthy nervous system, sometimes I think we make it too difficult. The basic keys to nutrition are easy: a balanced diet of good, high quality ingredients; absence of potentially toxic substances; species-appropriate foods (grass and grain for horses; meats with some veggies for dogs); and moderation. The older I get, the more I believe that a really balanced diet (lots of choices during the week’s meals) may be most important. You cannot beat fresh, organic, unprocessed, unpreserved foods for a truly top-quality diet. • Supplements. Use supplements if you have a compelling reason to do so; in some cases they can be helpful. But keep in mind that evidence is mounting that supplements given in the form of pills or capsules are not nearly as effective as their counterparts found in natural foods. And, out-of-balance supplements or those given in excess may be more problematic than helpful. Examples of nerve-enhancing supplements include antioxidants such as vitamins A, C, and E; a balanced vitamin B supplement; and magnesium (given in a format that balances it with other minerals). Gingko (Ginkgo biloba) improves nerve function, possibly due to its ability to enhance oxygen flow to the brain. Other herbs such as hawthorn berries (Crataegus species) enhance blood flow, and most herbs contain high levels of antioxidants. • Socialization. In today’s crowded world, dogs absolutely need to be socialized. Any dog that hasn’t learned to stay out of the street (or that isn’t being walked on a leash), or that has not learned how to approach other dogs without inciting a fight, is a trauma case waiting to happen. • Chiropractic. There is nothing better for health and healing, especially for the nerves that come from the spinal cord and supply peripheral body parts, than periodic chiropractic adjustments. A “well-oiled” spine is an essential component for overall health, allowing for a full range of pain-free movement and creating a flow of healthy nervous input to dependent muscles and organs. Conversely, “stuck” joints often create irritated nerves, which then adversely affect the organs and muscles they supply. • Homeopathy and acupuncture are two powerful medicines that may be helpful for treating many nervous system diseases. Many practitioners have had good success treating epilepsy with acupuncture, and particular homeopathic remedies seem to fit some of the symptoms of a variety of nervous system diseases. The protocol for using either of these medicines will vary with the disease symptoms, as they are presented. Don’t be surprised if the way of diagnosing and the approach to providing alternative therapies differ from the way conventional Western medicine typically approaches disease and healing. • Tincture of time. It was once thought that nerve cells did not regenerate and that animals did not generate new nerve cells, but recent evidence clearly shows this to be wrong. Damaged nerve cells can regenerate, and nerve cells continue to develop as long as we stimulate the need for them (i.e., as long as we stimulate the brain to think and act). Often, especially after a traumatic event, all that is needed for healing is to be patient and wait for it to happen. • Heart to head connection. Consider your dog’s emotional health as an integral part of her/his nervous system. A little loving contact goes a long toward creating and maintaining a healthy CNS. The recent advances into the science of the brain indicate that it may truly be the body’s inner health maintenance organization. When the brain is emotionally relaxed, satisfied, and happy, it sends the message to all other body parts that everything is under control, that homeostasis has been achieved. On the other hand, however, putting the animal under emotional stress alters the biochemical messages being generated by the brain, and the result is that all other body parts are also stressed. Also With This Article“What You Can Do”-Dr. Randy Kidd earned his DVM degree from Ohio State University and his PhD in Pathology/Clinical Pathology from Kansas State University. A past president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, he’s author of Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Dog Care and Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Cat Care.