Download the Full June 2010 Issue PDF

Collared!

Recently I made four visits to three different vet clinics within a week. The visits raised my blood pressure considerably, and not out of concern for my dog. I was more concerned for the other dogs I saw there, and all for the want of the simplest equipment imaginable: collars and ID tags. I’d estimate that only about half the dogs were wearing collars – and only one dog in 10 was wearing identification.

288

Perhaps I wouldn’t find this so outrageous if I haven’t had the experience (many times over) of finding dogs who are clearly lost, and who are not wearing ID tags. In the almost four years since I moved to a small town in a rural county in Northern California, I’ve picked up six different dogs whom I found wandering along country roads. Five were wearing collars; none had tags, and so I transported each dog to the county animal shelter. I can only hope that their owners found them there. I also found one dog in town who was wearing ID tags. I called the number on that tag and the dog was picked up by his owner within five minutes of my call.

The ID-free dogs I saw at the vet offices especially bothered me. The very fact that they were receiving veterinary attention meant that they were owned and cared for – and yet those owners had not provided the bare minimum in protecting these dogs from a trip to the animal shelter (at best) if they happen to get loose and get lost. There are many far worse (and far more likely) scenarios that can befall a lost and anonymous dog. Some folks might just decide to keep the dog; in my county, it’s just as likely that a dog lacking ID would be suspected of being a threat to livestock and shot.

Maybe you’re one of those people who don’t keep a collar and tags on your dog because you think your dog will never, ever have an opportunity to escape. What about the solicitor who leaves your gate open? What if, through no fault of your own, you were in a car accident and your dog was thrown out of your car and ran away in a panic? What if a fire broke out in your house while you were away, and the firemen had to break the door down to fight the fire, and your dog ran away in the confusion? Don’t scoff; this happened to one of my sister’s friends; dryer lint caught fire, the house started burning, the neighbors called 911, firemen responded, and the family dog got out of the house – and was hit by a car and killed – all in the half-hour during which the dog’s owner was buying groceries.

A few months ago I saw a large dog, clearly dead, lying on the shoulder of the highway that bisects my town. She was wearing a collar, and I had some faint hope that ID tags were affixed to the collar; at least I could call the owners and let them know that their dog had been killed. As sad as this news would be, I know I’d want someone to do that for me, if I lost my dog. It wasn’t a surprise to find that the collar lacked tags. Someone, somewhere, is still wondering what happened to their dog.

How To Stop the Dog from Chasing Children

[Updated January 28, 2019]

Dogs and kids can be the best of playmates. Sometimes they develop this relationship all on their own, and sometimes they need some outside assistance to become fast friends. It’s not uncommon for the basic dog-kid foundation to be solid, with just a few rough edges that need smoothing. One of the common rough spots is when your excited dog wants to chase after and nip your excited children. Here are five things you can do if your canine youngster wants to play a little too roughly with your human youngsters:

1. Supervise your dog diligently.

Dog trainers say it all the time: Never leave small children alone with even the most trustworthy dog. If you’re present when play starts to escalate out of control, step in and calm things down. Without your intervention, your dog gets reinforced for her inappropriate behavior. Chasing a squealing child is a very fun game! – at least for the dog, and sometimes for the child – until a bite happens. Behaviors that are reinforced are more likely to be repeated and to increase in intensity, and are harder to modify or extinguish.

2. Make Household Rules

Of course children need to be able to run around without worrying about a canine ambush. Set some firm house rules that are designed to minimize chase-and-nip games. If your dog loves kids, it’s fine to allow your small children and their friends to hang out with the dog (under direct supervision, of course); your older children and their friends can hang out with the dog with less supervision. In either case, one house rule should be that before rowdy play happens, the dog gets escorted to a safe place away from the action, and gets something wonderful (i.e., stuffed Kong) so she doesn’t feel punished. Another house rule is “absolutely no deliberately antagonizing the dog to encourage her to chase or nip.” Violation of these rules should result in loss of dog-companionship privileges for a pre-determined period.

3. Train Your Dog to Stay Off Kids

The better-trained your dog is, the easier it is for you to calmly and quickly intervene. A gentle “come” or “down” cue for a dog who is under good stimulus control is all it takes to abort the chase-and-nip game. Deliver high-value reinforcement when your wonderful dog responds immediately to your cue to keep those responses strong. Behaviors that are reinforced are more likely to repeated and repeated with enthusiasm.

4. Involve Your Children in the Training Program

The best way to train your children to interact appropriately with your dog is to include them in your dog’s training program. You can teach even very young children how to elicit a polite sit from your dog by raising their hands to their chest – if you’ve taught your dog this body-language signal to sit. Teach your young humans how to play “trade” with your dog by offering a treat or a toy to get her to give up something she has in her mouth, then encourage them to play games that direct her energy – and her teeth – toward something other than a child’s skin or clothing, such as a ball or Frisbee. The better you are at teaching your children what to do (and reinforcing them for it!), the more they will do what you want them to. Just like dogs!

5. Read Up on Dogs and Kids

Trainer/author/mother Colleen Pelar has written two excellent books on dog-kid relationships. Her first, Living with Kids and Dogs Without Losing Your Mind, is loaded with excellent advice for parents. Her second, Kids and Dogs; A Professional’s Guide to Helping Families, is written for those dog training professionals (like me) who don’t have human children of our own. If your trainer regularly instructs you to do things regarding your dog and child that you feel are unrealistic, read this book and then hand it off to her.

Of course, not all dogs love kids. If your basic dog-kid relationship foundation is shaky, then you need to do a whole lot more than the above five things. That’s an entirely different article! If that’s the case, don’t let them interact until you consult a good, positive behavior professional.

Canine News You Can Use: June 2010

British Kennel Club registers first “Low Uric Acid” Dalmatian; so far, the AKC won’t.

In January 2010, the Kennel Club (Britain’s equivalent of our American Kennel Club) accepted the registration of its first “Low Uric Acid Dalmatian” (LUA Dalmatian), despite protests from breed clubs.

288

As explained in “Cast in Stone,” page 8, Dalmatians carry a genetic mutation that predisposes them to the formation of life-threatening urate bladder stones. It is not unusual for Dalmatians to need several surgeries to remove stones during their lifetimes. Feeding a low-purine diet helps prevent urate stones, but the problem can be so severe that in some cases the only option is euthanasia. Genetic testing has shown that there are no longer any Dalmatians in the U.S. – or likely the U.K. – that carry the normal gene.

In 1973, Bob Schaible, PhD, a geneticist and breeder of Dalmatians, crossed a Dalmatian with a champion Pointer, a similar breed thought to be closely related to the Dalmatian. His goal was to produce offspring who look like purebred Dalmatians but carry a normal gene for uric acid production. The breeding was successful from a health standpoint, though the new Dalmatians’ spots were smaller and less defined than usual. The offspring and their descendants were backcrossed to purebred Dalmatians for many generations, resulting in dogs that are indistinguishable from purebred Dalmatians.

In 1981, Dr. Schaible, with the approval of the Dalmatian Club of America’s board of directors, was granted American Kennel Club (AKC) registration for two dogs from the fourth generation of the backcross. However, when the Dalmatian Club’s general membership found out and caused an uproar, the AKC refused to register any offspring from these dogs. (So much for being “the dog’s champion.”) The passage of time has not softened its stance, either. There has been no policy change since then. In fact, the Dalmatian Club banned any discussion of the topic for 22 years.

In 2006, the membership was polled again, and a majority supported continuing the testing and breeding of backcrossed Dalmatians, but in 2008, the membership again voted against registering these dogs. As a result, all Dalmatians remain affected by the defective gene that causes high uric acid.

Despite this, Dr. Schaible has continued his Dalmatian Low Uric Acid Project or Backcross Project, breeding to the best lines of Dalmatians. The offspring are now 14 generations removed from the single Pointer outcross and more than 99.98 percent of their genes are identical to those of purebred Dalmatians.

The British television show “Pedigree Dogs Exposed,” which aired in August 2008, called attention to genetic problems affecting some breeds. The public’s overwhelming response to the program has resulted in changes in breed standards and judging, as well as a commitment from the (British) Kennel Club to consider registering dogs from outcrossings and inter-variety matings if doing so may contribute to the breed’s health. In keeping with these changes, the Kennel Club now registers LUA Dalmatians, subject to certain conditions, including examination by qualified judges to confirm that their appearance meets breed standards.

The AKC’s stance as of 2002 is that a two-thirds supermajority of a breed club’s membership must approve before it will consider opening the breed’s stud book. It’s time for the AKC to take the lead in improving the health of purebred dogs – and for breed fanciers to put the health of their dogs above an insistence on genetic purity. – Mary Straus

Training Small Dog Breeds

There’s a reality show that airs on TLC called Little People, Big World that chronicles the daily lives of the Roloffs, an Oregon family made up of both small (both parents are under 4 feet tall) and average-sized people. The series tastefully portrays how every day activities and seemingly uneventful situations can affect the family members differently based on their size and how society views them. Most importantly, it successfully shows that size does matter, particularly in a society built for the average-sized person. I just wish there was a show, or at least an effective way to get that point across regarding small dogs. They and their owners have long been misjudged and misunderstood.

288

According to the 2009 American Kennel Club registration statistics, nearly half of the top 20 breeds are small dogs that weigh less than 20 pounds at full adulthood. This appeal makes a lot of sense. Small dogs are much more portable and can be taken virtually anywhere, even to places where dogs usually aren’t allowed (not that I advocate that). They require less space, making them a viable choice for apartment or condo dwellers. They’re much easier to exercise; a regular-sized room can easily be converted to a play area without moving even a single piece of furniture.

Despite all this, intolerance and a lack of understanding of smaller dogs is prevalent in society. Stereotypes deem them “snippy,” “yappy,” and “bratty” – and perhaps the most cutting of all, “not even real dogs.” I’ve heard this even from people who consider themselves dog lovers!

Small dogs and those who choose to share their lives with small dogs are different. Throughout my 25-plus years as a professional in the field of dog behavior and training, it’s been my experience that small dog owners do tend to be much more protective of their dogs (sometimes to the point of being overprotective) and are less likely to socialize their dogs or attend group training classes. They also tend to be more tolerant of – and apt to make apologies and excuses for – their dogs’ inappropriate behavior.

Before you write me off as just another one of those little dog haters, let me also say that I currently share my household with three Malteses: 9-lb. Leo, 7-lb. Andrew (with whom I appeared on the CBS show “Greatest American Dog”), and Geoffrey, who at five years of age still barely tips the scale at 3 pounds. However, I also have four big dogs, and have had large dogs for most of my life, affording me the opportunity to see both sides of the spectrum. But unfortunately, throughout all my years teaching group training and socialization classes, I’d estimate that the owners of small dogs (15 lbs and less) make up barely 10 percent of the people who come to – or even inquire about – my classes. In fact, it’s probably closer to 5 percent. That’s very sobering.

Unfortunately, it’s also understandable. Stop in and look at an average puppy kindergarten class; what you’ll usually find will be a boisterous 15-week-old Labrador Retriever puppy jumping all over his owner on one side of the room, a Shepherd-mix lunging at the Husky pup bouncing on the other side of him, and then there might be an already 40-lb. Rottweiler puppy dragging her owners through the door. All the new puppy parents are clearly having difficulty trying to maintain control of their dogs while holding onto the leash and a bag full of treats.

Is it any wonder that this environment might be uninviting for the new, nervous parent of a 4-lb. toy Poodle puppy? Subsequently, many owners of small dogs never return to that or any other training class or socialization session. As a result, too many toy breed and small dogs miss out on crucial training and positive socialization experiences at the time they need it the most, which in turn leads to the undesirable behaviors we sometimes see in small dogs that perpetuate the stereotypes.

This is why I say “bravo” to any trainer or facility that includes “Mighty Mites” or “Tiny Tots” classes, geared toward the small dog, in its programming. While these types of classes may not be as prevalent as I’d like, I do encourage small dog owners to seek them out. If no class exists in your area, go and talk to your area trainers and request one, or at least find out if they provide modifications for the smaller dog in their regular classes.

That said, failure to find a suitable group class for you and your little dog is not an excuse to fail to train your small dog! By being proactive and tweaking your training environment a little, you can successfully train your small dog at home, or even better, manipulate and modify the environment in a regular group training class to meet your dog’s specific needs.

288

Level the training field

Have you ever really tried to imagine how different the environment looks to a dog who stands less than 10 or 12 inches tall? Undoubtedly everything and everyone likely looks bigger and much farther away. Just for a little perspective, try placing an alarm clock at the top of a 20 foot ladder. Then get down on all fours and look up. How far away does that clock look to you now? Is your neck feeling a little strained? Are you finding it difficult to read the numbers? All in all, it’s just not very comfortable, is it?

That’s just a small glimpse of what it might be like for a little dog to look at your face and try to decipher your expression. Getting and keeping your dog’s attention is paramount in training, and it’s difficult to accomplish that with a dog who finds it physically uncomfortable to look up at you. It’s also uncomfortable for a handler – especially if she has a bad back – to bend over (almost to the floor) again and again.

Therefore, the first thing that must be done is to give that dog a boost, helping him get closer to you – and especially your hands, which give cues and deliver treats and petting as rewards. Placing the dog on a table or chair is a good option. I love to “sofa train” my little ones with quick little training sessions while they’re sitting on the sofa with me. This makes the sofa much more than a place to cuddle; now it becomes a special place to work and have fun as well.

Another great option is to grab a yoga mat and have a seat on the floor next to your dog. Again, establishing focus and attention will be easier when both of you are closer to each other. These options are good starting points to introduce behaviors, and just like shaping any other behaviors, you can gradually bring the dogs’ focus upward until you’re eventually standing in a full, upright position.

On target

Something that should be in every small dog owner’s toolbox is a target stick. Since our arms only reach so far, and constantly bending over can literally be a pain, extending your reach by two or more feet can be a lifesaver.

Target sticks add this extension and can be used as a lure or focal point for your small dog. They can be purchased ready-made or can be fashioned from a wooden dowel with a baby spoon taped onto the end. I’ve even seen some people use a back scratcher as a target! Rubbing a high value food (like squeeze cheese, soft cream cheese, or peanut butter) onto the end of the stick will “load up” the target stick and make it an object of desire for your dog. Soon, the dog will follow that stick anywhere. Suddenly, teaching loose leash walking becomes much more manageable. You can click and reward the small dog without breaking a stride. Like any lure, the target stick can and should be faded once the dog has learned what position is the most rewarding.

With a little creativity you can find additional items that can be used as training aids for small dogs, most of which are inexpensive and readily available. You can set up a mini-agility course using those small, portable tunnels intended for toddlers, plungers for weave poles, and shoe boxes for tables or pause boxes. Dogs of any size love to run, jump, and go through tunnels, but most importantly these kinds of activities are great for relationship-building and instilling confidence.

Even little dogs have noses, so why not try some scent discrimination activities? Place treats in a mini-muffin tin and then cover the treats by placing mini tennis balls or ping pong balls on top. Encourage your dog to sniff the tin and “find” the treats by moving the tennis balls and claiming his reward. Almost anything you’d use for training a larger dog can be modified and downsized for a smaller dog if you use your imagination.

288

Social work

The importance of socialization cannot be disputed. Unsocialized dogs are often fearful and socially inept; they have difficulty reading the body language signals of other dogs or performing appropriately friendly signals themselves. Those small dogs who bark and snarl and kick up a fuss when they see other dogs – especially dogs who are much bigger than they are? They are displaying fear-based aggression, but their behavior endangers themselves and their owners if they antagonize another dog into starting a fight. And dogs of any size who get scared and snap at people often end up getting permanently left at home, or surrendered to a shelter.

Here’s the bottom line: if you want your small dog to be comfortable with people and other dogs, you must socialize him or her, and as early as possible. Again, your goal is to find a group puppy class conducted by a knowledgeable instructor who knows how to provide a positive socialization experience for all puppies, regardless of size. However, if you can’t find a class like this, you need to create opportunities for yourself. There are many small dog “meet up” groups. You can find them through an Internet search, or through your favorite veterinarian, trainer, or independent pet supply store.

Before participating in one of the socialization sessions, though, attend without your dog and speak with the participants and facilitator. Surely some of them have puppies, so inquire about setting up a playgroup for the puppies only. If other small breed puppies can’t be found, don’t count out larger breed puppies. Gentle, calm, and easygoing puppies of all breeds do exist, and frankly, positive interactions with dogs who are larger than your pup are just as important (if not more so).

If your small dog is already an adult and has problems getting along with other dogs, seek out an experienced behavior professional. Counter-conditioning and desensitization exercises and other training can increase your dog’s comfort with other dogs and improve his response.

Even though your dog should be able to get along with other dogs (of any size), for his own safety, it’s best to exercise and socialize him at dog parks that have a special section for small dogs. Sadly, we’ve heard numerous reports of small dogs getting injured and even killed by larger, overstimulated, and predatory dogs in dog parks.

Smaller is good, too

I’ll be the first to admit that I do have a different kind of relationship with my little dogs than I have with my larger ones. A little dog’s size and dependency on us does promote a kind of intimacy that is hard to explain to someone who hasn’t experienced it. Remember how much you loved to coo, cuddle, and pick up your Golden or Labrador puppy when he was small? Can you blame a small dog owner for enjoying those experiences throughout her small dog’s life?

Further, if I have to maneuver through a crowd or need to get from point A to point B quickly, I’ll hoist my small dog into my arms so I can get to my destination faster. I don’t do it because I’m too lazy to get my small dogs to walk on lead politely. I do it because it’s more convenient – and because I can!

Despite my years of experience with dogs of all sizes, I consider myself fortunate to have experienced all the joys of sharing my life with my little (and well-trained and well-socialized) dogs. No matter how much you love your small dog, I’d be willing to bet that you would enjoy her even more if she were better behaved, so get busy training!

Laurie C. Williams is a dog trainer, rally obedience judge, and owner of Pup ’n Iron, Canine Fitness and Learning Center, in Fredericksburg, Virginia. See “Resources,” page 24, for contact information.

Reinforce Your Dog’s Bite Inhibition

BITE INHIBITION: OVERVIEW

- Take the time to teach your puppy the invaluable skill of inhibiting his bite. It could be one of the most important lessons he learns – one that will serve him well for a lifetime.

- Supervise children with your puppy so your puppy doesn’t get reinforced for inappropriate biting, and so your children don’t have to suffer the pain of uninhibited puppy mouthing.

- Resist the pressure from some members of the dog community to use pain and force to suppress your puppy’s biting behavior. You know there’s a better way.

My dog bites me. A lot. Scooter, the 10-pound Pomeranian we adopted from the shelter after he failed a behavior assessment (for serious resource-guarding), has bitten me more times than I can count. Most of the time I don’t even feel his teeth. He has never broken skin, and the few times I have felt any pressure, it’s been because I’ve persisted in what I was doing despite his clear request to stop. Scooter has excellent bite inhibition.

In the dog training world, bite inhibition is defined as a dog’s ability to control the pressure of his mouth when biting, to cause little or no damage to the subject of the bite. We know that all dogs have the potential to bite, given the wrong set of circumstances. Some dogs readily bite with little apparent provocation, but even the most saintly dog, in pain, or under great stress, can be induced to bite. When a bite happens, whether frequently or rarely, bite inhibition is what makes the difference between a moment of stunned silence and a trip to the nearest emergency room for the victim (and perhaps the euthanasia room for the dog).

A bite is at the far end of a long line of behaviors a dog uses to communicate displeasure or discomfort. To stop another dog, human, or other animal from doing what he perceives to be an inappropriate or threatening behavior, the dog often starts with body tension, hard eye contact, a freeze, pulling forward of the commissure (corners of the lips). These “please stop!” behaviors may escalate to include a growl, snarl (showing teeth), offensive barking, an air-snap (not making contact), and finally, an actual bite. The dog who does any or all of these things is saying, “Please don’t make me hurt you!”

Some foolish humans punish their dogs for these important canine communications. “Bad dog, how dare you growl at my child!” Punishing your dog for these warning signals can make him suppress them; he’ll learn it’s not safe to let you know he’s not comfortable with what you’re doing -and then bites can happen without warning. (See “Understand Why Your Dog Growls,” October 2005.)

Others ignore the signals and proceed with whatever was making the dog uncomfortable. This is also foolish, because it can prompt the dog to express his feelings more strongly, with a less inhibited bite that might break skin and do damage.

The wise dog owner recognizes the dog’s early signals, and takes steps to reduce or remove the stimulus that is causing the dog to be tense, to avoid having her dog escalate to a bite. She then manages the environment to prevent the dog from constant exposure to the stressful stimulus, and modifies her dog’s behavior to help him become comfortable with it. Sometimes, however, even the best efforts of the wisest dog owners can’t prevent a bite from happening. If and when it does, one hopes and prays that the dog has good bite inhibition.

Installing Bite Inhibition

In the best of all worlds, puppies initially learn bite inhibition while still with their mom and littermates, through negative punishment: the pup’s behavior makes a good thing go away. If a pup bites too hard while nursing, the milk bar is likely to get up and leave. Pups learn to use their teeth softly, if at all, if they want the good stuff to keep coming. As pups begin to play with each other, negative punishment also plays a role in bite inhibition. If you bite your playmate too hard, he’ll likely quit the game and leave.

For these reasons, orphan and singleton pups (as well as those who are removed from their litters too early) are more likely to have a “hard bite” (lack of bite inhibition) than pups who have appropriate interactions for at least seven to eight weeks with their mother and siblings. These dogs miss out on important opportunities to learn the consequences of biting too hard; they also fail to develop “tolerance for frustration,” since they don’t have to compete with littermates for resources. They may also be quicker to anger -and to bite without bite inhibition -if their desires are thwarted. Note: Being raised with their litter doesn’t guarantee good bite inhibition; some dogs have a genetic propensity to find hard biting (and its consequences) to be reinforcing; others may have had opportunity to practice and be reinforced for biting hard.

Your dog may never bite you in anger, but if he doesn’t have good bite inhibition you’re still likely to feel a hard bite when he takes treats from your fingers -and removes skin as well as the tasty tidbit.

If you find yourself with a puppy who, for whatever reason, tends to bite down harder than he should with those needle-sharp puppy teeth, you need to start convincing him that self-restraint is a desirable quality. You can’t start this lesson too early when it comes to putting canine teeth on human skin and clothes. Ideally, you want to teach your pup not to exert pressure when mouthing by the time he’s five months old, just as his adult canine teeth are coming in, and before he develops adult-dog jaw strength. Here are the four R’s of how to do it:

1. Remove

When your puppy bites hard enough to cause you pain, say “Ouch!” in a calm voice, gently remove your body part from his mouth, and take your attention away from him for two to five seconds. You’re using negative punishment, just like the pup’s mom and littermates. If he continues to grab at you when you remove your attention, put yourself on the other side of a baby gate or exercise pen. When he is calm, re-engage with him.

2. Repeat

Puppies (and adult dogs, and humans) learn through repetition. It will take time, and many repetitions of Step #1, for your pup to learn to voluntarily control the pressure of his bite. Puppies do have a very strong need to bite and chew, so at first you’ll “ouch and remove” only if he bites down hard enough to hurt you. Softer bites are acceptable -for now. If you try to stop all puppy biting at once, both of you will become frustrated. This is a “shaping” process (see “Fun Training Techniques Using Shaping,” March 2006).

At first, look for just a small decrease in the pressure of his teeth. When he voluntarily inhibits his bite a little -enough that it’s not hurting you -start doing the “ouch and remove” procedure for slightly softer bites, until you eventually shape him not to bite at all. By the time he’s eight months old he should have learned not to put his mouth on humans at all, unless you decide to teach him to mouth gently on cue.

3. Reinforce

Your pup wants good stuff to stick around. When he discovers that biting hard makes you (good stuff) go away, he’ll decrease the pressure of his bite and eventually stop biting hard. This works especially well if you remember to reinforce him with your attention when he bites gently. It works even better if you use a reward marker when he uses appropriate mouth pressure. Given that your hands are probably full of puppy at that particular moment, use a verbal marker followed by praise to let him know he’s doing well. Say “Yes!” to mark the soft-mouth moment, followed by “Good puppy!” praise to let him know he’s wonderful.

4. Redirect

You probably are well aware that there are times when your pup is calmer and softer, and times when he’s more aroused and more likely to bite hard.

It’s always a good idea to have soft toys handy to occupy your pup’s teeth when he’s in a persistent biting mood. If you know even before he makes contact with you that he’s in the mood for high-energy, hard biting, arm yourself with a few soft toys and offer them before he tries to maul your hands. If he’s already made contact, or you’re working on repetitions of Step #1, occasionally reinforce appropriate softer bites with a favorite squeaky toy play moment.

If there are children in the home with a mouthy puppy, it’s imperative that you arm them with soft toys and have toys easily available in every room of the house, so they can protect themselves by redirecting puppy teeth rather than running away and screaming -a game that most bitey pups find highly reinforcing.

It is possible to suppress a puppy’s hard biting by punishing him when he bites too hard. That might even seem like a quicker, easier way to get him to stop sinking his canine needles into your skin. However, by doing so, you haven’t taught him bite inhibition. If and when that moment comes where he really does feel compelled to bite someone, he’s likely to revert to his previous behavior and bite hard, rather than offering the inhibited bite you could have taught him.

Teaching Bite Inhibition to An Adult Dog

Teaching an adult dog to inhibit his bite is far more challenging than teaching a puppy. A dog easily reverts to a well-practiced, long-reinforced behavior in moments of high emotion, even if he’s learned to control his mouth pressure in calmer moments.

I know this all too well. Our Cardigan Corgi, now six years old, came to us at the age of six months with a wicked hard mouth. Hand-feeding her treats was a painful experience, and I implemented a variation of the “Ouch” procedure. Because she was biting hard for the treat rather than puppy-biting my flesh, I simply said “Ouch,” closed my hand tightly around the treat, and waited for her mouth to soften, then fed her the treat. Hard mouth made the treat disappear (negative punishment); soft mouth made the treat happen (positive reinforcement). She actually got the concept pretty quickly, and within a couple of weeks could thoughtfully and gently take even high value treats without eliciting an “Ouch.”

She still can take treats gently to this day, except when she’s stressed or excited; then she reverts to her previous hard-bite behavior. When that happens, I close the treat in my fist until she remembers to soften her mouth, at which time I open my hand and feed her the treat. So, while our bite inhibition work was useful for routine training and random daily treat delivery, if Lucy ever bites in a moment of stress, arousal, fear and/or anger, I have no illusions that she’s going to remember to inhibit her bite. Of course, I do my best to make sure that moment doesn’t happen.

Because I have more leeway with Scooter and his excellent bite inhibition, it’s tempting to be a little complacent with him. I try not to. One of Scooter’s “likely to bite” moments is grooming time. The poor guy has a horrible undercoat that mats, literally, in minutes. This is a highly undesirable Pomeranian coat characteristic. I could groom my first Pomeranian, Dusty, once a week without worrying about mats. I have to groom Scooter every night.

Of course he hates it; brushing always causes him some discomfort as I work to ease the tangles out without pulling too hard on his skin. We’ve made progress in the year we’ve had him; I can comb the top half of his body without encountering much resistance, but I can feel him tense up as I approach the more sensitive lower regions. Rather than relying on his good bite inhibition to get us through, I continue to use counter-conditioning and desensitization. I feed him treats (or have my husband Paul feed him) as I groom, or let him lick my hands (an activity he enjoys mightily -and one I can tolerate in place of his biting) while I comb out the tangles.

Whether you’ve taken the time to teach your puppy good bite inhibition or had the good fortune to inherit a dog who has it, don’t take it for granted. Continue to reinforce soft-mouth behavior for the rest of his life, and don’t be tempted to push the envelope of his tolerance just because you can. Even saints have limits.

What to NEVER Do if Your Dog Bites

Over the years, I’ve cringed at a variety of puppy-mouthing modification suggestions. Here are some of the things you don’t want to do:

Alpha-Rolls

Whole Dog Journal readers might think “no alpha-rolls” goes without saying by now, but I still see clients with mouthy puppies who have had their trainers, dog walkers, dog-owning friends, or veterinarians tell them to alpha-roll their bitey pups. Don’t do it. You are likely to elicit a whole lot more biting — truly aggressive biting — as your frightened pup tries to defend himself. (See “Puppies Who Demonstrate ‘Alpha’ Behavior,” WDJ July 2006.)

High-Pitched Yelps

This might surprise you. It’s often suggested by positive trainers, some of whom I respect greatly, but I don’t recommend it. The theory is that a high-pitched yelp makes you sound like a puppy in pain and communicates to your young dog in a language he understands.

The fallacy with this theory is that we think our feeble attempt to speak “puppy” with our human yelp might really communicate the same message as a real puppy yelp – like

trying to speak a foreign language by mimicking what we think the sounds are, without actually knowing any of the words. In my experience, the high-pitched yelp is as likely to incite an excited biting puppy to a higher level of arousal (and harder biting) as it is to tell him he bit too hard and should sofien his mouth. Don’t do it. A calm “Ouch!” sends a much more consistent, useful, and universal message, which is simply, “That behavior makes the good stuff go away.”

Hold the Dog’s Mouth Closed

Another classic bad idea. What self-respecting puppy wouldn’t struggle and try to bite harder with this inappropriate restraint? All the while, you’re giving your pup a bad association with your hands near his face, which isn’t going to help with grooming, tooth-brushing, mouth exams, or even petting. Don’t do it.

Push Your Fist Down His Throat

Seriously. For the same reasons as in the prior two suggestions, this is a really bad idea.

Don’t do it.

Push His Lip Under His Canine Tooth So He Bites Himself

There really is no end to the inappropriate ways people can think up to try to change behavior. This is another one that has a strong possibility of causing your pup to associate hands near his face with pain. Don’t do it.

Bite Your Puppy Back

Yep, some folks actually recommend this. I shouldn’t have to say this, but I will anyway: Don’t do it.

Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, is Whole Dog Journal’s Training Editor. Miller lives in Fairplay, Maryland, site of her Peaceable Paws training center.

Treatment and Prevention of Kidney and Bladder Stones

BLADDER STONES IN DOGS: OVERVIEW

1. Get an accurate diagnosis and follow nutritional guidelines for your dog’s type of uroliths.

2. If your dog is prone to urate stones, consider switching to a low-purine home-prepared diet.

3. Avoid low-protein prescription foods when they are unnecessary or ineffective at preventing stone formation.

4. For male dogs who continue to form stones, consider urethrostomy surgery to greatly reduce the risk of obstruction.

Canine kidney and bladder stones may be painful and life-threatening, but an informed caregiver can help prevent them. By far the most common uroliths or stones in dogs are struvites (see “Canine Kidney Stone and Bladder Stone Prevention“) and calcium oxalate stones (see “Preventing Bladder and Kidney Stones in Dogs“). These two types represent about 80 percent of all canine uroliths.

Now we address the remaining stones that can affect our best friends: urate, cystine, calcium phosphate, silica, xanthine, and mixed or compound uroliths.

Urate or Purine Stones

Of the remaining stone categories, urate or purine stones are the most common. They contain ammonium acid urate, sodium urate, or uric acid.

Only 6 to 8 percent of all uroliths are urate or purine stones, but their presence in certain breeds is significant. Dalmatians, English Bulldogs, Russian Black Terriers, and Large Munsterlanders develop urates because of a genetic metabolic abnormality. Miniature Schnauzers and Yorkshire Terriers do so as a result of their tendency to have portosystemic shunts, which are abnormal blood vessels that bypass the liver, predisposing dogs to urate stones. These stones can form in dogs of any age, from very young puppies to seniors, but the most common age for forming urates is 1 to 4 years.

Of the breeds that develop urate stones, Dalmatians are most adversely affected. Between 1981 and 2000, the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine’s Minnesota Urolith Center analyzed 7,560 stones from Dalmatians. Of these, 97 percent were from males and 95 percent were composed of urates. It’s estimated that between 27 and 34 percent of male Dalmatians form urate stones, while the incidence in females is much lower.

It’s tempting to assume that any stone a Dalmatian forms is a urate, but although 97 percent of stones from male Dalmatians were urate, they also included small percentages of struvite, xanthine, calcium oxalate, cystine, calcium phosphate, silica, and mixed or compound stones. The uroliths formed by female Dalmatians were 69 percent urate and 29 percent mixed or compound, with 2 percent struvite and 0.7 percent xanthine. Correct identification is a crucial first step in treating and preventing uroliths in all breeds, including Dalmatians.

The culprits in urate stone formation are purines, a type of organic base found in the nucleotides and nucleic acids of plant and animal tissue. As dietary purines degrade, they form uric acid, which is best known in human medicine for its connection to gout, a sharply painful form of arthritis. In susceptible dogs, purines trigger the formation of urate uroliths.

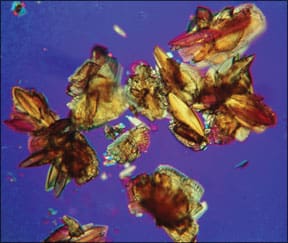

Urate stones are radiolucent – that is, they cannot be identified in abdominal X‑rays – so their diagnosis is often made by the use of ultrasound, contrast dye X-rays, or analysis of urinary crystals or stones that were collected or removed.

Signs of Stones

As noted in our previous articles, an accurate diagnosis is essential because what prevents or treats one type of stone may actually cause another. The only way to be sure of a stone’s identity is to have it analyzed. However, your veterinarian can make an educated guess based on urinary pH; the dog’s age, breed, and sex; the identification of urinary crystals; radiographic (X-ray) density; whether infection is present; and certain blood test abnormalities.

When should your veterinarian become involved? As soon as you notice symptoms or, if your dog’s breed is strongly predisposed to developing stones, even sooner. Not all bladder and kidney stones are dangerous; some are flushed during urination while still small in size and others remain unnoticed in the kidney or bladder. Stones don’t create complications until they interfere with urination. It’s important to become familiar with urinary stone symptoms, which include straining to urinate, blood or pus in the urine, painful or difficult urination, increased frequency of urination, the passage of small amounts of urine, licking the genitals more than usual, “accidents” in house-trained dogs, or discomfort in the lower back.

A dog who strains and then releases a flood of urine may have just passed a stone and should be examined. If you can find the stone, take it with you so it can be accurately identified. A dog who is unable to urinate needs immediate medical attention because a plugged urethra can cause urine to back up into the system, resulting in a ruptured bladder or kidney failure. A bladder that has been stretched can lose muscle tone, making it difficult to empty completely, which can lead to infection or more stones. Bladder stones are much less likely to cause an obstruction in females than in male dogs, thanks to the shorter and wider urethra in females.

Increasing urine volume and opportunities to void urine are important factors in preventing uroliths of all types. The more a dog drinks and the more frequently he urinates, the less concentrated his urine and the less likely the formation of crystals that can become stones. Encourage your dog to drink more by adding water to his food and offering flavored water in addition to plain. For dogs with urate stones, you can add salt

to food to increase thirst (start with a pinch, watch your dog’s response, and add more in small steps until your dog drinks more water), but added salt should be avoided for dogs prone to forming cystine, calcium phosphate, or silica stones.

Be sure that your dog has frequent opportunities to urinate because when dogs have to hold their urine for extended periods, their urine is more likely to become supersaturated, at which point its minerals begin to precipitate out as crystals.

Treating and Preventing Urate Stones

The key to keeping urate-forming dogs healthy is to feed them a low-purine diet. Without the purines that trigger urate stone formation, even susceptible dogs can lead normal lives.

Some Dalmatian owners believe that giving dogs who are prone to forming stones only mineral-free distilled water has helped prevent more stones from forming. However, no scientific evidence for this exists. The quantity of water the dog consumes may be more important than its mineral content.

Because urate stones develop in acidic urine, an added prevention strategy is to feed foods that have an alkalizing effect. In general, meat is an acidifying food while most fruits and vegetables have an alkalizing effect. Vegetarian dog foods are sometimes recommended for this reason, but we consider vegetarian foods incomplete. Also, foods that use soy as a protein source are inappropriate for dogs who are prone to forming urate stones because soy is high in purines. However, soy-free vegetarian foods could be used as a base to which eggs, yogurt, cheese, and other low-purine protein sources are added.

The same is true of some dog food pre-mixes, such as Sojo’s Grain Free Dog Food Mix. Sojo’s Complete is based on sweet potatoes, turkey, and eggs and might also be appropriate for dogs with hyperuricosuria (excessive amounts of uric acid in the urine). Avoid mixes that contain a lot of alfalfa, oats, barley, or other foods that are high in purines (see “Purine Content of Various Foods”).

Urate stones can be dissolved with a combination of a low-purine diet, urine alkalization, and control of secondary infections. The target range of urine pH during dissolution is 7.0 to 7.5. Care must be taken not to alkalize too much, making the urine pH higher than 7.5, because that can lead to the formation of calcium phosphate stones or shells around urate stones, making them difficult or impossible to dissolve.

The xanthine oxidase inhibitor allopurinol (brand name Zyloprim) may be prescribed short-term to reduce or inhibit the dog’s production of uric acid, which can help dissolve stones. This drug should not be used in patients with portosystemic shunts. A low-purine diet must be fed while giving allopurinol, as otherwise it predisposes dogs to the formation of xanthine stones and shells, making dissolution difficult. The long-term use of allopurinol as a preventative is not recommended but can be considered at low dosages when problems persist despite other treatment.

On average, it takes about 3½ months for stones to dissolve using allopurinol in combination with a low-purine diet and urinary alkalizination, but it can take as little as one month or as long as 18 months. As stones become smaller, they may move into the urethra and cause obstruction.

Some cases of severe kidney stones presumed to be ammonium urate resolved spontaneously following surgical shunt correction alone.

Monitoring Urine pH

Urinary pH can be monitored using test strips with the goal of maintaining a neutral (7.0) pH in dogs prone to urate stones. Test strips can be held in the urine stream or urine can be collected in a paper cup, bowl, or other container for testing. Collecting the urine makes it possible to check for tiny stones or gritty “gravel” that the dog might be passing as well as any blood, pus, or other indications of infection. The recommended testing time is first thing in the morning, before feeding.

A change in urinary pH does not indicate the presence or absence of stones but does reveal conditions that are more or less likely to trigger stone production and will show the effect of dietary changes on the dog’s pH. A sudden jump in pH may signal a bacterial infection, which requires medical attention. It’s important to control urinary tract infections in dogs prone to forming stones. If urine remains acidic and crystalluria (the formation of urinary crystals) persists, alkalizing agents such as potassium citrate or sodium bicarbonate can be added.

Testing for Canine Hyperuricosuria

Hyperuricosuria is characterized by the excretion of high levels of uric acid leading to urate stone formation. After the defective gene that causes hyperuricosuria was discovered by researchers at the University of California, Davis, a test was developed to detect the mutation associated with the disease. This test is valid for all breeds.

Dogs affected by hyperuricosuria have two copies of the mutation, one inherited from each parent. Dogs with only one copy of the mutation are symptom-free carriers who pass the mutation on to an average of 50 percent of their offspring. Breeders can use DNA testing to identify carriers and effectively erradicate hyperuricosuria from their lines in breeds other than Dalmatians. (At present, all Dalmatians registered in the United States are affected by the mutation. See “LUA Dalmatians”. When both dam and sire are clear of the mutation, all of their puppies will be clear as well.

The DNA test identifies dogs in three categories: clear of hyperuricosuria (the dog has two copies of the normal gene and no mutation), a carrier of hyperuricosuria (the dog has one copy of the normal gene and one of the mutation), or affected with hyperuricosuria (the dog has two copies of the mutation, causing high acid levels that can lead to urate stone disorders).

All dogs affected with hyperurico-suria are potential urate stone-formers. At any time, a combination of high-purine foods, insufficient fluids, insufficient opportunities to urinate, and overly acidic urine might cause the formation of urate uroliths. Periodic routine urinalysis to check for urate crystals can be used to monitor dogs with hyperuricosuria. The most accurate sample for this purpose is collected in the morning, assuming the dog has not urinated all night, so the urine is more concentrated. The sample should be collected in a clean glass, plastic, or other chemically inert container. To avoid false crystallization, the sample should not be refrigerated and should be tested within 30 minutes or as soon as possible.

While many Dalmatians never generate stones, it isn’t safe to assume that they can’t. In one widely reported case, a 13-year-old Dalmatian who had never shown symptoms began receiving two spoonfuls of a new supplement per day. Prior to this, his diet had been the same for all of his adult life. Within a few weeks, his urinary tract became completely obstructed by urate stones. While the supplement was low in protein (only 14 percent), its protein source was liver, a high-purine food.

The Low-Purine Diet

Reducing purines in food is an effective way to reduce the risk of urate stones. Because most high-protein foods are also high in purines, veterinarians often recommend switching urate-forming dogs to a low-protein diet. However, it is not the quantity of protein that causes urate problems; it’s the type of protein. Dalmatians and other urate-prone dogs thrive on protein-rich diets that are low in purines, while these same dogs can develop stones after eating low-protein foods that contain even small amounts of high-purine ingredients. Low-protein diets can lead to nutritional deficiencies when fed to adult dogs for long periods, and they are not appropriate for puppies and pregnant or nursing females at all. (See “The Side Effects of Low-Protein Diets,” below.)

Because it’s difficult to find commercial pet foods that are low in purines without being nutritionally deficient, many owners of urate-forming dogs feed a home-prepared diet. Australian veterinarian Ian Billinghurst, whose book Give Your Dog a Bone introduced the BARF (Bones and Raw Food or Biologically Appropriate Raw Food) diet to dog lovers around the world, describes how to adapt his menus for urate-forming dogs in a report posted at several websites.

“In Western countries today,” he says, “I am led to believe that a typical homemade diet for stone formers would contain about 80 percent rice, 10 percent vegetables, and 5 percent meat. This is an appalling diet to feed any dog. This is borne out by dogs forced to endure it. They suffer from numerous problems including continual hunger, a lack of energy, poor coat condition, and difficulty in maintaining weight or severe losses of weight.” Such a diet is not only deficient in protein, fat, vitamins, and minerals, he says, but it does not prevent stone formation.

The raw meaty bones Dr. Billinghurst recommends are chicken necks, chicken backs, chicken wings, and turkey necks. “Use plenty of puréed or pulped vegetables,” he says, “including lots of leafy greens. The diet could also include eggs, cottage or ricotta cheese, yogurt, and olive or flaxseed oil, supplemented with vitamin B complex, vitamin E, kelp, and a teaspoon of cod liver oil several times a week.” Cod liver oil is important for urate-forming dogs fed a homemade diet that does not include liver.

Feeding a changing variety of eggs, cheese, dairy products, and small amounts of medium-purine meat, poultry, and fish along with low-purine vegetables, fruits, and supplements – as well as ample water to keep urine diluted – can help any urate-forming dog stay healthy and happy.

Cystine Stones

Cystine is a sulfur-containing amino acid essential to the health of skin, hair, bones, and connective tissue. Excess cystine is normally filtered by the kidneys so that it doesn’t enter the urine, but some dogs are born with cystinuria, an inherited metabolic disorder that prevents this filtering action. When cystine passes into the urine, it can form crystals and uroliths.

Cystine stones are rare, representing 1 percent or less of uroliths identified in laboratories. Although any breed can develop cystinuria, certain breeds are most affected. An estimated 10 percent of male Mastiffs have cystinuria. It is also common in Newfoundlands, English Bulldogs, Scottish Deerhounds, Dachshunds, Staffordshire Bull Terriers, and Chihuahuas. Cystine stones are faintly radiopaque, which makes them more difficult to see on X-rays than stones that contain calcium.

There are at least two types of cystinuria. The more severe form affects Newfoundlands and, rarely, Labrador Retrievers, and possibly some other breeds and mixes. In these dogs, males and females are equally affected (though as always, males are more likely to become obstructed). The age at onset can be as young as 6 months to 1 year. Recurrence of stones following surgery is more rapid in these dogs, and they are more likely to form kidney stones. The gene that causes cystinuria in these breeds has been identified and a simple, reliable genetic test can identify both affected dogs and carriers.

In other breeds, dogs with cystinuria are almost always male. No genetic test is available for them, though the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine (PennVet) is collecting blood samples from affected Mastiffs and their genetic relatives to try to produce a DNA test. The average age at onset of clinical signs is about 5 years.

A basic urinalysis can sometimes detect cystine in urine, though this is the least reliable method of detection. A nitroprusside (NP) test performed at the University of Pennsylvania (PennGen) is considered more reliable. A quantitative amino acid analysis performed by PennGen or a human medical laboratory is most reliable but very expensive. If cystine is found in the urine on any of these tests, the diagnosis is considered positive for cystinuria, though that doesn’t necessarily mean the dog will form stones.

Unfortunately, a negative result on any of these tests does not guarantee that the dog is “clear.” Note that sulfa drugs and supplements, including sulfa antibiotics, MSM, and Deramaxx, may cause false positive results.

“Cystinuria is a particularly frustrating condition to manage,” says San Francisco Chronicle pet columnist Christie Keith, who started a Canine Cystinuria e-mail list and website when one of her Scottish Deerhounds developed cystine uroliths. “A dog known to have cystinuria may go his whole life without obstructing, while another dog, never diagnosed, can have a life-threatening obstruction as his first symptom. It’s not known at this time why some dogs with cystinuria form stones and others do not.”

Cystine, like all amino acids, is one of the building blocks of protein. That’s why most veterinarians (including many kidney specialists) prescribe a low-protein diet, speculating that reducing the cystine supply will reduce the formation of cystine stones. Another common recommendation is to alkalize the dog’s urine because cystine stones form in acid urine.

Unfortunately, says Keith, these strategies are ineffective. “Most of us on the Canine Cystinuria list have found that diet and urinary alkalization have failed to prevent our dogs from forming stones,” she says, “and they have sometimes caused other problems, including other types of stones that form in alkaline urine. If the urine goes into acidity even briefly, cystine stones can form and they won’t dissolve just because alkaline urine is achieved soon after. In addition, feeding ultra-low-protein diets can be dangerous, especially to giant breeds and breeds prone to cardiomyopathy.” (See “The Side Effects of Low-Protein Diets”, below.)

It’s important to provide your dog with extra fluids and frequent opportunities to urinate in order to keep his urine from becoming supersaturated. Salt should not be added to increase fluid consumption for dogs with cystinuria; according to studies conducted on humans, a low-sodium diet may decrease the amount of cystine in the urine.

If urine alkalization is attempted, the target pH is 7.0 to 7.5; higher can predispose dogs to calcium phosphate uroliths. Potassium citrate is preferred for alkalization when needed rather than sodium bicarbonate because sodium may enhance cystinuria.

Cystine stones cannot be dissolved with diet or supplements, but two prescription drugs can help dissolve and prevent them. Cuprimine (d-penicillamine) has potentially serious side effects but is less expensive and more readily available, and many dogs do well on it. According to Keith, Thiola (tiopronin, also referred to as 2-mercaptopropionylglycine or 2‑MPG), has fewer side effects, but one of them is the depletion of the owner’s bank account. Maintaining a giant-breed dog on Thiola can cost as much as $500 per month. Because the severity of cystinuria tends to decline with age, the dosage of preventative medications can sometimes be decreased or even stopped.

Dissolution requires a combination of medication, low-protein diet, and urinary alkalinization. Even then it may not be successful or practical for a dog with numerous stones. When it does work, dissolution commonly takes one to three months.

For some dogs, the solution has come not from prevention strategies or medication but from surgery. “It sounds extreme,” says Keith, “but many of us who have stone-forming male dogs with cystinuria have opted for a scrotal urethrostomy. This surgery redirects the dog’s urethra away from the penis to a new, surgically created opening in front of the scrotum.”

The wider opening that results enables males to more easily pass small stones and help prevent urinary blockages. “While future obstruction is not impossible,” says Keith, “this procedure reduces the risk substantially.” Still, she cautions, this surgery should not be undertaken lightly. It’s expensive, requiring the expertise of a skilled board-certified surgeon, and because the affected area is rich in blood vessels, there can be significant post-surgical bleeding, though the surgery is not particularly painful.

“The good news,” she says, “is that many dogs, including stone-formers and those who had serious complications when their condition was first diagnosed, have lived not just normal but longer-than-normal lives.”

The Remaining Three

Like cystine stones, stones composed of xanthine, calcium phosphate, and silica are rare, each representing less than 1 percent of analyzed uroliths. Ironically, they often occur while the patient is undergoing treatment for the prevention of other stones.

– Although xanthine is a type of purine, xanthine stones are associated not with diet but with the use of allopurinol. Xanthine crystals almost never occur naturally, though they have been reported in some cats, Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, and Dachshunds. The average age at onset is 6 to 7 years. Like urate stones, they are radiolucent; that is, they cannot be seen on X-rays.

In some cases, discontinuing allopurinol while feeding a low-purine diet has dissolved xanthine uroliths, but in general, treatment consists of surgical removal, urohydropropulsion (a nonsurgical procedure performed with the dog under anesthetic, in which the bladder is filled with saline through a catheter, and the bladder is manually squeezed to force stones out through the urethra), or lithotripsy (the use of high-energy sound waves to break up the stones).

A low-protein diet is usually recommended for dogs receiving allopurinol treatment (to help prevent formation of xanthine uroliths); but again, what’s really needed is a low-purine diet.

– Calcium phosphate stones often develop when the urine is over-alkalized (at a pH greater than 7.5), in an effort to prevent the formation of calcium oxalate, urate, or cystine stones. The average age at onset is 7 to 8 years, but these stones have been found in dogs of all ages, including puppies and seniors.

Calcium phosphate stones are commonly called apatite uroliths, with hydroxyapatite and carbonate apatite the most common. They are radiographically dense, so they are easily seen on X-rays. Uroliths composed primarily of calcium phosphate are rare and associated with metabolic disorders such as hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s disease), hypercalcemia, renal tubular acidosis, or excessive calcium and phosphorus in the diet.

Because they cannot be dissolved medically, these stones are usually removed surgically, though that may be unnecessary if the stones are clinically inactive (not growing or causing problems). They have been known to dissolve spontaneously following parathyroidectomy surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism. Unless the patient has a metabolic condition that contributes to calcium phosphate stones, the strategies used for prevention are similar to those used for calcium oxalate stones, although it’s important to avoid excessive alkalization of the urine.

Medications that can enhance calcium excretion, including prednisone and furosemide (Lasix), should be avoided if possible. Salt should not be added to the diet, as sodium increases urinary calcium.

– Silica stones are most common in male German Shepherds, Old English Sheepdogs, Golden Retrievers, and Labrador Retrievers, although other breeds and mixed breed dogs have developed them as well. More than 95 percent of silica stones occur in males. The problem can develop in dogs as young as four months or as old as 12 years, but most stones occur in dogs aged 6 to 9 years. Silica stones are radiopaque and can be seen on X-rays. No relationship has been found between urinary pH and silicate urolith formation.

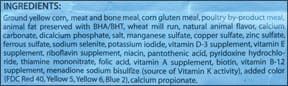

The formation of silica stones is associated with diets high in cereal grains, particularly corn gluten and soy bean hulls, both of which are high in silicates. Corn gluten and soy bean hulls (also called soybean mill run) are ingredients in low-quality prescription diets and dog foods.

Other foods that are high in silica, and which should be avoided, include the hulls of wheat, oats, and rice (hulls are found in whole grains); sugar beets; sugar cane pulp; seafood; potatoes and other root vegetables; onions (which shouldn’t be fed to dogs, anyway); bell peppers; asparagus; cabbage; carrots; apples; oranges; cherries; nuts and seeds; grains; soybeans; and the herbs alfalfa, horsetail, comfrey, dandelion, and nettles. Bentonite clay, a mineral supplement, is also high in silicates.

Because no drug or diet dissolves silica stones, they may be removed surgically, flushed out with urohydropropulsion, or shattered with lithotripsy; no treatment may be required for clinically inactive stones. Silica stones do not usually recur, but it makes sense to feed a diet that is high in protein from animal sources and low in plant foods, including fiber and bran. As with all stones, keep the urine diluted by increasing fluids and giving your dog frequent opportunities to urinate. Don’t add salt, which is another source of silica.

Dogs who drink water from sources containing sand may develop silica uroliths, so water that contains silica (a primary mineral in sand) should be avoided. In hard-water areas, distilled water is recommended for dogs who form silica stones. Silica stones have also been associated with pica, an eating disorder that causes dogs to eat dirt, rocks, and other non-food items.

Mixed and Compound Uroliths

Most bladder stones are caused by a single type of mineral. Sometimes a stone consists of two or more minerals in approximately equal proportions, in which case it is called a mixed urolith. These stones are rare, comprising only 2 percent of analyzed uroliths.

A stone that consists of a core mineral surrounded by a smaller amount of a different mineral is called a compound urolith. These make up 10 to 12 percent of analyzed stones. Compound uroliths can sometimes be identified based on differing radiographic density of their stone layers.

Compound uroliths develop when a stone’s environment changes, such as when a struvite stone is treated by reducing urinary pH, magnesium, and phosphorus, resulting in a calcium oxalate shell around the struvite core. Struvite shells caused by infection commonly form over calcium oxalate and other cores, especially since all stones predispose dogs to bladder infections.

One treatment strategy is to try to dissolve the outer layer first. This is especially effective for stones with an infection-induced struvite shell, which make up more than 80 percent of compound uroliths with cores other than struvite. The struvite shell should dissolve with appropriate antibiotic or infection-fighting treatment. X-rays can be used to monitor dissolution. Once the outer shell disappears, treatment strategy switches to the inner core, also called the nucleus, or the stones may then be small enough to remove by urohydropropulsion.

More than half of the compound uroliths analyzed in 2002 by the Minnesota Urolith Center contained a calcium oxalate core, and almost all of these were surrounded by a struvite shell caused by infection. Unlike calcium oxalate uroliths, these compound uroliths were found primarily in female dogs; again, this is because the female dogs’ anatomy makes them more susceptible to urinary tract infections, which play a role in causing struvite stones. Treatment and prevention should be focused on controlling infections and reducing the risk of calcium oxalate stones.

Stones with a struvite core made up amost a quarter of compound uroliths, more than half of which were surrounded by a calcium phosphate shell and most of the rest by a calcium oxalate shell. As is common with infection-induced stones, most of these dogs were female.

Urinary acidifiers can contribute to urinary calcium that leads to the formation of calcium-containing stones. Treatment is the same as for struvites: appropriate medication for the infection and possibly a reduced-protein diet short-term to help dissolve the stones quickly. Urinary acidification is not recommended due to the increased risk of calcium oxalate and calcium phosphate formation.

Small percentages (3 to 5 percent each) of compound uroliths were comprised of the following:

- Silica core. Most of these had a calcium oxalate shell and were found in male dogs. Since both silica and calcium oxalate stones are associated with plant-based foods, diets containing substantial plant proteins should be avoided.

– Calcium phosphate core surrounded by struvite or calcium oxalate shells. These are treated the same way as struvite or calcium oxalate stones.

– Urate core, most of which were surrounded by struvite. Treatment is aimed at controlling the infection along with management of the urate core.

– Compound uroliths with a core or shell of xanthine are treated by discontinuing or reducing the dose of allopurinol.

Sulfa drugs may create a shell around struvite uroliths when used at high doses for prolonged periods, or in dogs with acidic or highly concentrated urine. For this reason, sulfa drugs should be avoided when treating lower urinary tract (bladder) infections, particularly for dogs known to have stones or one of these risk factors.

Preventive treatment should focus on whatever minerals comprised the stone’s inner core. As with all types of stones, increasing fluid intake and opportunities to urinate are recommended. Adding salt to the diet is not recommended, however, as it increases urinary calcium and calcium is commonly found in uroliths.

The Side Effects of Low-Protein Diets

Without sufficient protein in the diet, protein is pulled from muscles to meet the body’s requirements. Nutritionally inadequate, low-protein diets should never be fed to puppies or dogs who are pregnant or nursing, and they can cause health problems if given to adult dogs for prolonged periods.

According to the Merck Veterinary Manual (9th Edition, 2008), “The signs produced by protein deficiency or an improper protein-to-calorie ratio may include any or all of the

following: weight loss, skeletal muscle atrophy, dull unkempt coat, anorexia, reproductive problems, persistent unresponsive parasitism or low-grade microbial infection, impaired protection via vaccination, rapid weight loss after injury or during

disease, and failure to respond properly to treatment of injury or disease.”

Ultra-low-protein diets such as Hill’s Prescription u/d have been linked to dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) in English Bulldogs, Dalmatians, and other breeds. Dogs with cystinuria, which predisposes dogs to carnitine deficiency even when a normal-protein diet is fed, are particularly at risk. Some Newfoundland dogs are prone to taurine deficiency leading to DCM even when fed regular commercial diets, especially lamb and

rice diets, though many manufacturers now add taurine to their lamb and rice diets to help prevent this side effect.

According to a study of cardiac function in healthy dogs fed protein-restricted diets published in the American Journal of Veterinary Research in 2001, “Dogs fed protein-restricted diets can develop decreased taurine concentrations…The possibility exists that AAFCO [Association Of American Feed Control Officials] recommended minimum requirements are not adequate for dogs consuming protein-restricted diets. Our results also revealed that, similar to cats, dogs can develop DCM secondary to taurine deficiency, and taurine supplementation can result in substantial improvement in cardiac function.”

Low-protein diets are not needed in most cases to prevent the development of kidney or bladder stones. lf you choose to feed a low-protein diet, you should supplement with carnitine and taurine to help prevent the development of DCM. Dogs with cystinuria may benefit from supplementation even if fed a regular diet. Suggested preventative dosages are 25 to 50 mg L-carnitine and 5 mg taurine per pound of body weight two or three times a day. For example, a 50-pound dog should receive 1,250 to 2,500 mg L-carnitine and 250 mg taurine twice or three times a day. Higher dosages are needed to treat DCM.

You can also add eggs and dairy products to a low-protein diet for dogs with hyperuricosuria to increase protein.

Preventing Recurrence

Once your dog’s stones are successfully treated, you’ll want to use the strategies described in this article to help keep them from coming back. Stone-forming dogs can be monitored by their veterinarians with X‑rays, ultrasound, and urinalyses.

Infection-induced struvites can recur in as little as a few days to a few weeks, while calcium oxalate and silica stones may take a few months to recur. Cystine and urate stones can recur rapidly. Some dogs continue to form stones despite diet changes and medical therapy. For them the key is monitoring with radiographic imaging (X-rays or ultrasound) at least every 3 to 6 months (more often to start with and for rapidly recurring types) in order to detect stones while they are still small enough to pass through the urethra using urohydropropulsion or catheter-assisted retrieval.

A final solution for males with recurring stone blockages is urethrostomy surgery, which redirects the flow of urine to avoid its normal narrow passage.

CJ Puotinen is the author of The Encyclopedia of Natural Pet Care and other holistic health books. She lives in Montana, and is a frequent contributor to Whole Dog Journal. San Francisco Bay Area resident Mary Straus has spent more than a decade investigating and writing about canine health and nutrition topics for her website, DogAware.com.

Dogs Can Do the Math

Trainers are fond of saying that we train our dogs every day, whether or not we realize it. What they mean is, our dogs pay scrupulous attention to our behavior (even when it seems that they are ignoring us) so they can put themselves in a good position to profit from their association with us. If we are doing something that has potential benefits for them, they tend to tag along and turn on the charm; if we engage in activities that are distinctly unrewarding to them, they usually take a pass.

288

This is why your dog is more likely to follow you into the kitchen than, say, into the bathroom. Your presence in one room reliably predicts the appearance of food, and sometimes he gets some of it! Your presence in the other room, though, is a total bore – and sometimes it predicts a dog bath! Heading for the living room? Well, it depends. It’s one thing if it’s nighttime and you’re carrying a bowl of popcorn. It’s another thing entirely if it’s midday and you’re dragging a vacuum. One situation is promising for a dog and one is not. It’s not rocket science; it’s simple observation and deduction.

I’ve been trying to explain this concept to my husband, who sometimes becomes frustrated with our dog, Otto. Brian has certain expectations of dogs in general, and one is that they should be happy – nay, eager – to jump in the back of a truck at any time. Some dogs relish the opportunity to take a drive with their owners, even if it’s just to the post office and back. But Otto does not enjoy riding in automobiles of any kind. In the car, he curls himself into a ball on the floor of the backseat and lies there looking glum until we arrive at our destination. In the truck, he lies down behind the cab and doesn’t get up until we turn off the engine. As a result, Otto’s willingness to get in the car or truck is completely conditional.

For example, the presence of a bait bag full of treats at night almost always means we’re going to a dog-training class, which he enjoys immensely. When I head to the truck wearing my hiking shoes or bike shorts, a fun run for Otto often follows, and so at these times, Otto will jump right in.

Other things predict Otto’s discomfort. The appearance of Brian’s fishing rod has often translated into a very long drive on bumpy, winding roads, and/or hours of lying tied up on a cold riverbank. That math is just not that difficult to do, even for a dog.

But at other times the problem is positively algebraic. Nancy + hiking shoes + treats sometimes = a trip to the vet. And once, Brian was alone (this often means fishing) but didn’t have the fishing rod with him. That turned out to be a trick question; Brian snapped Otto’s harness onto the safety belt and then went to get the fishing rod. In other words, we’ve unwittingly trained Otto to be wary of the car and truck.

Think about what you might be doing to reinforce your dog’s undesirable behavior, and what you could do to reward him for the behavior you want.

My Dog Wakes Up Too Early!

Those last few minutes of sleep before the alarm goes off are a treasured sanctuary where we hide in dreams before the reality of the world intrudes. Few dog owners appreciate it when their dog wakes up too early, robbing them of those golden moments. But some dogs seem to have an uncanny knack for anticipating the alarm by 15 or 20 minutes, and manage to routinely do just that.

Of course, puppy owners expect to be awakened by their baby dogs – or they should. It’s unreasonable to think a young puppy can make it through the night without a potty break. Crated or otherwise appropriately confined, even an eight-week-old puppy will normally cry when his bowels and bladder need emptying, rather than soil his own bed. When this happens you must get up and take your pup out to empty his bladder and bowels, and then immediately return him to his crate so he doesn’t learn to wake you up for a wee-hours play or cuddle session.

Adult dogs, however, barring a health problem, should wait for you to get up rather than pushing back your wake-up time in eager anticipation of breakfast, or other morning activities. If your grown-up dog has made it his mission to make sure you’re never late for work (or breakfast) by waking you up every morning before your alarm does, try this:

1) Rule out medical conditions.

Make sure your dog doesn’t have a legitimate reason for getting up early. If he has a urinary tract infection or digestive upset, or some other medical issue that affects his elimination habits or otherwise makes him uncomfortable, he may have to go out 30 minutes (or more!) before you normally get up to let him out.

2) If your dog wakes up too early, tire him out the night before.

A tired dog is a well-behaved happy dog and a late sleeper. Exercise uses up much of the energy that he presently can’t wait to wake you up with – and also releases endorphins, which regulate mood, producing a feeling of well-being. Tiredness promotes sleeping in, and endorphins help reduce anxieties that may play a role in his early-bird activities.

3) Feed him earlier/ better; make “last call” later.

Increase the time between your dog’s last meal and his last bathroom opportunity to minimize the chance that he’s waking you up because he really has to go. It only takes a few “I really have to go” mornings to set an early-riser routine, especially when rising is reinforced with, “Well, we’re up now, no point in going back to bed . . . here’s your breakfast!” Don’t forget that high-quality diets are more digestible, which reduces fecal output, which reduces early-morning urgency.

4) Reduce stimuli in the bedroom.