[Updated August 10, 2017]

Recently we’ve heard from a number of dog owners who are concerned about the use of ethoxyquin to preserve fish meal that is used in dog foods. We’ve had one e-mail forwarded to us several times expressing worry over links between undeclared ethoxyquin in pet foods and canine cancer.

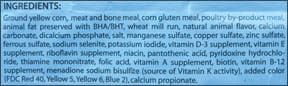

We have long advised owners to pass over dog food that contains artificial preservatives such as butylated hydroxyanisole (BHA), butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT), tert-butyl hydroquinone (TBHQ), propyl gallate, and ethoxyquin, in favor of products made with natural preservatives, such as tocopherols (vitamin E), citric acid (vitamin C), and rosemary extract.

Though synthetic preservatives were once – as recently as 20 years ago – the usual preservative found in all dry dog foods, today, they appear only on the labels of low-cost and lower-quality products. Pet food companies appreciate the fact that artificial preservatives are less expensive, and they preserve food longer and more reliably than their natural counterparts. But owners who have their dogs’ life-long health foremost in their minds are willing to pay more for more natural products that don’t needlessly expose their dogs to potentially toxic chemicals.

It is possible, however, for pet foods to contain ethoxyquin or other artificial preservatives even if those substances don’t appear on the list of ingredients.

Preservatives Myth Busting

When we get worried (or panicked) mail about this issue, the writer is usually concerned about fish meal that’s been loaded with ethoxyquin. The apparent source of this concern is the fact that the U.S. Coast Guard requires that fish meal that is transported on boats be treated with ethoxyquin, to prevent the volatile fatty acids in the product from spontaneously combusting while traveling on the high seas.

It turns out, though, that this is just part of the story. Only fish meal that is shipped by boat must be treated to prevent combustion; plenty of fish meal is manufactured on land and is not subject to any Coast Guard regulations. Also, the Coast Guard allows the use of other antioxidants to treat the fish meal – and even permits untreated fish meal to be shipped, if the shipper can provide documentation that the product does not display self-heating properties.

What seems to be a surprise to most dog owners is the fact that all animal protein meals – and animal fats – are treated by their manufacturers with preservatives. It’s not just fish meal! Chicken meal, lamb meal, beef meal . . . preservatives are added to all of them.

As alarming as this might sound, it’s only prudent; without some sort of preservation, the fat in these ingredients is subject to oxidation and rancidity. Oxidation is an irreversible process, so antioxidants must be added as early in the food manufacturing process as possible. However, natural preservatives can be used; when buying ingredients for use in their products, the preservation system used is just one of a number of specifications the pet food manufacturers can make. Naturally preserved meat meals cost more and are not as shelf-stable as artificially preserved meat meals, so the decision to use only naturally preserved animal protein meals in their products is a costly and deliberate choice that pet food manufacturers must make.

Preservatives Not on the Label

It’s the fat in meat or poultry meal that needs protection from oxidation. Animal protein meals (i.e., “chicken meal,” “lamb meal,” etc.) usually contain 10 to 14 percent fat. While the preservative used to protect the major fat sources in a dog food (such as “chicken fat”) must be declared on pet food labels, the amount of preservative used in protein meals is generally considered low enough to meet the definition of an “incidental additive,” which is not required to appear on the product label. At least, that’s one explanation for why the preservatives used in protein meals don’t have to appear on pet food labels.

A more prevalent explanation is that there is no legal requirement for pet food makers to disclose substances that were added to an ingredient before it reaches the pet food manufacturing plant. We’ve been told countless times that a pet food maker is responsible for disclosing only the ingredients they themselves mix in during the manufacture of the pet food. In other words, “We didn’t put ethoxyquin in the fish meal; it was already there when we bought the meal! And because we didn’t put ethoxyquin in our pet food, we don’t have to list it among our products’ ingredients.”

We’ve heard this claim so many times, in fact, that we were surprised to learn that it’s not wholly accurate. Dave Dzanis, DVM, PhD, DACVN, a consultant on animal nutrition, labeling, and regulation, writes in his December 2009 column in the trade publication Petfood Industry:

“For a labeling exemption as an ‘incidental additive’ to apply, the level in the final product would have to be low enough to where it no longer had any technical or functional effect [21 CFR 501.100(a)(3)(i)]. Considering that fish meal processors may add 1,000 ppm or more, the residual amount of ethoxyquin in the petfood still could be functional, hence would have to be declared.

“Also, FDA regulation 21 CFR 573.380 expressly specifies that any animal feed containing ethoxyquin must declare it, which is unique language compared to the codified requirements for other approved food additives. That statement can be interpreted as superseding any labeling exemption. In fact, if memory serves me, in the 1990s FDA did advise that ethoxyquin must be declared whether added directly or indirectly, irrespective of source or level.”

We’re not sure how this information can be reconciled with the fact that many pet food companies use fish meal that has been preserved with ethoxyquin, yet ethoxyquin does not appear on the label. Perhaps most companies do not fully understand or have a different interpretation of these rules, and the regulations are simply not enforced.

A Closer Look at Ethoxyquin

Ethoxyquin is a chemical antioxidant and was approved as a pet food additive in 1959. It is used to preserve certain spices (chili powder, paprika, and ground chili only), and is also used as a pesticide and a rubber preservative. Residual levels from animal feed are allowed in meat, poultry, and eggs for human consumption.

The FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine (CVM) began receiving reports in 1988 of health issues that pet owners and some veterinarians suspected could be linked to ethoxyquin in pet foods, such as allergic reactions, skin problems, major organ failure, behavior problems, and cancer. Studies done by Monsanto (the manufacturer of ethoxyquin) at the request of the CVM, showed dose-dependent effects on liver enzymes and pigment. As a result, in 1997 the CVM asked the pet food industry to voluntarily lower the maximum level of ethoxyquin in dog foods from 150 ppm (parts per million) to 75 ppm. It said that most pet foods never exceeded the lower amount, even before this recommended change.

Is this level safe? According to a document produced by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), “Dogs are more susceptible to ethoxyquin toxicity than rats, with elevated liver enzymes and microscopic findings in the liver occurring at doses as low as 4 mg/kg/day over a 90-day feeding period.” The “4 mg/kg” means 4 mg ethoxyquin per kilogram of the dog’s body weight (not the weight of the food).

Per CVM calculations, 4 mg/kg body weight is the equivalent of 160 ppm in food, just barely above the upper limit that is still allowed in pet food. It’s possible that longer-term ingestion could reduce the amount needed to cause adverse effects and increase the potential for harm. In addition, dogs who eat more food in relation to their body weight, such as puppies, nursing females, and working or other very active dogs, are at risk of exceeding the amount known to cause liver damage.

Let’s look at the fish meal that is processed at sea and treated with ethoxyquin at time of production. Coast Guard regulations say that this fish meal must contain at least 100 ppm ethoxyquin at time of shipment. It’s questionable, though, how much ethoxyquin remains in a finished pet food made with this fish meal. The amount of fish meal used and the method and temperature of the dog food’s manufacture will affect the amount of ethoxyquin present in the final product. We’ve seen claims from companies whose dog foods contain fish meal preserved with ethoxyquin that the foods contain 5 ppm or less ethoxyquin.

Is this lower level safe? No one knows for sure, but it’s certainly less toxic than the amounts that the FDA allows in pet food. And it’s within the limits allowed in some human foods (0.5 to 5 ppm in meat and fat, with higher amounts allowed for spices).

The FDA and pet food industry officials defend the use of ethoxyquin, saying that ethoxyquin is safer than rancid fats. While this may be true, artificial preservatives are not the only way to prevent rancidity. In addition, if ethoxyquin is safe, why is it not permitted to be added to human foods (other than three spices), and why is the acceptable level for pet foods 50 times the residual amount allowed in human food?

Other Artificial Preservatives

Some dog breeders and consumer advocates suspect ethoxyquin of causing cancer, though studies don’t seem to bear that out except at very high levels (5,000 ppm or more). On this point, the EPA concluded, “potential cancer risk is below the Agency’s level of concern.” The artificial preservatives BHA and BHT are considered more likely carcinogens.

BHA and BHT are used in human and pet foods to keep fats from going rancid. Both have been linked to cancer in laboratory animals; it’s unknown whether they cause the same in people and dogs. There is evidence that certain people may have difficulty metabolizing BHA and BHT, resulting in health and behavior changes. Again, we don’t know if the same is true for our dogs.

Yet Another Matter of Trust

In the past, we’ve felt confident in recommending dog foods whose labels do not reflect the inclusion of artificial preservatives. That’s because we were under the impression that the maximum amount of artificial preservatives that could be present in a food whose label did not include them couldn’t possibly be high enough to cause harm. Since “doing the math” on the amount of synthetic antioxidants that can be present in a food whose label does not reflect its inclusion, though, we’ve become uneasy. It no longer seems sufficient to trust that a label review will always reveal the presence of artificial preservatives.

How then can a consumer find out if their dog’s food contains ethoxyquin, BHA, BHT, or other artificial preservatives? Unfortunately, there are no easy answers. You can contact the companies or check their websites, in an effort to find out if they use only naturally preserved meat meals in their foods. Some companies have started making “ethoxyquin-free” claims on their labels and product literature. One would have to trust the company’s answer, though; short of conducting expensive laboratory tests, there is no way to verify these claims. And even usually trustworthy companies can be duped by a contract manufacturer or ingredient supplier.

If you are adamant about avoiding any amount of artificial preservative in your dog’s diet, you would be well-advised to switch to a diet that does not contain meat meals. Canned foods and frozen diets are generally made with fresh and frozen animal ingredients, which are not usually treated with preservatives. Of course, feeding your dog a well-planned home-prepared diet made of fresh ingredients is the only way to be absolutely certain of ingredient content and quality.

Unfortunate that this info is only provided for profit. We as a society must be willing to share freely with our canine family when we all benefit from. Unless we set stronger boundaries and refuse to buy in there is no chance of changing for the betterment of our canine friends and society as a whole .