Download the Full June 2004 PDF Issue

Best Dog Treats

by Nancy Kerns

Rearranging the treats I was photographing for this article, I decided to spell a word. The decision to spell out the word “love” was not a conscious one, but it was automatic.

To our dogs, food is love – and security, affirmation, and reinforcement. When we give our dogs what trainers refer to as “high-value” treats – foods that are especially sweet, meaty, or pungent – our message gets through to them especially loud and clear. Behaviorists are highly appreciative of the ability of food treats to “classically condition” a dog to tolerate, and then even enjoy, environmental stimuli that he previously found frightening or threatening.

Plus, it’s fun for us, feeding our canine friends something they’re crazy about – the doggie equivalent of taking the kids out for doughnuts or ice cream.

Except, in the case of dog treats, we don’t have to worry about ruining our friends’ health with dangerous additives like high fructose corn syrup or partially hydrogenated oils (aka trans fats), which are found in many (if not most) snack foods in supermarkets. That’s because, unlike most human treats, dog treats can easily be found in healthy flavors and formulations that dogs find irresistible.

Hold out for health

The problem is, treats are probably the most likely of all dog-related items that a person might buy impulsively, without (horrors!) even a glance at the ingredients list. That’s because treats are often so darn cute! The packaging is frequently adorable and the names are hilarious.

Regular WDJ readers, however, know that you should never buy anything for your dog without a long, hard look at the ingredients panel, no matter how cute the cartoon dog on the label looks. It’s simply pointless to spend so much time and energy finding the best healthy foods for your dog if you are going to subvert your own efforts at health-building with low-quality, additive-filled garbage.

Nowhere are these deleterious junk foods more prevalent than at your local grocery store. We’ve said it before and we’ll say it again: Don’t buy commercially manufactured treats for your dog at the market. The treats they sell there (including most treats for kids) are just full of stuff your dog is better off without – stuff like low-quality by-products, sugar and corn syrup, and artificial colors. (See the examples of poor-quality, grocery-store treats in the sidebars.)

So where should you buy dog treats? For the utmost in quality, we recommend selecting fresh treats from local artisans. Our list of favorites includes treat makers such as Wet Noses (of Snohomish, Washington), Howling Hound Treats (Summerville, South Carolina), and Heidi’s Homemade Dog Treats (Columbus, Ohio), who hand-select the produce they buy from local farmers, as well as Rosie’s Rewards (Pray, Montana), who uses free-range Montana beef from local ranchers. Some of these folks have storefront shops; others rely on independent pet supply stores, veterinarians, and groomers to display and sell their wares. A few offer their goods only through phone orders or through their Web sites.

We have also been impressed by the number of folks who have managed to launch or grow their companies to national prominence while still manufacturing a top-quality product – companies like Cloud Star of San Luis Obispo, California (maker of Buddy Biscuits); Nature’s Animals of Mamaroneck, New York; and Pet Central of Sylvania, Ohio, maker of Waggers Dog Treats. These treats can be found in many pet supply stores and catalogs nationally, yet the company owners have maintained high standards for ingredient quality and consistent production.

What’s on the label

We hinted earlier that you have to read the label of any item that crosses your dog’s lips. Don’t be scared; it’s not that difficult! Your first task is to make sure the products don’t contain stuff that’s not good for dogs – such as artificial colors, flavors, and preservatives. Keep an eye out for lower-quality ingredients that indicate the maker may have cut corners to keep costs down, such as by-products or food fragments. If you are not sure you would recognize products meeting this description, compare the treats in the “Do Not Buy!” list with our selections; it’s really obvious if you just look at the ingredients list.

Those of us who have figured out which foods don’t agree with our own dogs due to food allergies or intolerances are also on the lookout for ingredients that may make our dogs itch, develop ear infections, or suffer painful gas or diarrhea. These ingredients vary from dog to dog, although many treat manufacturers focus on a handful of ingredients – including wheat, corn, soy, and eggs – that are purported to be more commonly implicated in canine allergies or intolerances than not. One company (Waggers) covers its bases by making three treats: one is “wheatless,” one is “meatless,” and one is “sweetless” – something for every dog!

Don’t worry about the presence of sweeteners in treats (unless your dog is diabetic, in which case you should focus on the meat-based treats). After all, the assumption is your dog will receive only a small number of these per day or week.

After you eliminate treats that have stuff that is bad for your dog, look for the good stuff: things like whole meats, grains, fruits, and vegetables. The more organic ingredients you see, the better, especially for dogs with chemical sensitivities and dogs who are combatting cancer (see sidebar).

Final notes

As is always the case when we review foods, we did not consider price in our selections. As ever, we implore you to remember that you get what you pay for. Inexpensive treats cannot contain good quality ingredients, because quality ingredients cost more. Of course, you also pay more for an especially cute presentation, such as the candy box style used by Happy Pet of San Francisco for its Canine Confections. You can’t beat a presentation like this, however, if you are looking for a special gift for a fellow dog-lover.

Be aware that we do not rate or rank-order our selections. A treat either meets our selection criteria (outlined in the sidebar) or it does not; there is no “top pick” or “best on the list.” And if you are familiar with a treat that meets our selection criteria, don’t worry that it’s not as good as our selections because it’s not on our list; we obviously haven’t reviewed every product on the market. Happily, there are many more good products than we could ever list.

We grouped our new selections into two categories: cookie-type treats, which contain grains; and meat-based treats that are usually carb-free. The selections are grouped alphabetically by category.

We’ve also listed all of our past selections that meet our current selection criteria. We’ve taken only a few products off our lists; this has occurred because we have made our selection criteria more stringent – not because those products are bad.

Also With This Article

Click here to view How to Identify and Pick Top Quality Dog Treats”

Click here to view “The Difference Between Quality Dog Treats and Unhealthy Dog Treats”

Click here to view “Top Quality Dog Treats”

Click here to view “How to Make Your Own Top-Quality Dog Treats”

Online Dog Chat Forums

by C.C. Holland

A few years ago, I underwent extensive knee surgery. Thanks to a skilled doctor, a supportive husband, and an Internet message board comprised of people who’d either undergone or were about to embark on similar procedures, I made it through with both my physical and mental health intact.

A couple of months ago, my dog, Lucky, decided to follow in her mom’s footsteps by tearing a ligament in her knee and undergoing her own surgery.

Before she went under the knife, I researched everything I could about the procedure. As I scoured the Web, it occurred to me that if there were message boards and online support groups for humans with knee injuries, maybe there’d be an equivalent for canines and their owners.

Sure enough, I found Orthodogs, a free group (set up through a Yahoo! service) that provides support, information, and advice to owners with dogs facing orthopedic problems. And then I discovered it was only the tip of the iceberg.

There are dozens of online groups aimed at dog owners out there, covering a wide range of topics – disabled dogs; dogs with cancer; dogs who have behavioral and training issues; and even grieving the loss of a pet. Groups range in size from a few dozen people to thousands; thanks to the Web, many include members from all over the globe. Most are free – and the criteria for membership are simply time, interest, and an Internet connection. To communicate, members “post” messages via interactive tools and can even contact each other directly through e-mail.

Can a virtual community of people you’ll probably never meet really help an owner cope with a dog’s problems? Yes, say mental-health professionals.

“Finding like-minded people who understand exactly what you’re feeling and who can respond to you basically 24 hours a day is very helpful,” says Darlene Mininni, Ph.D., author of the forthcoming book, The Emotional Toolkit, and an expert in coping strategies.

In addition, says Dr. Mininni, the act of typing out your messages provides a therapeutic outlet.

“That’s an added bonus, because writing about your feelings helps you make sense of them,” she says. “It’s the same benefit of writing in a journal – and there are tons of studies that demonstrate how doing that can improve your feelings.”

Betty Carmack, a professor of nursing at the University of San Francisco, has been running a pet-loss counseling group in the Bay Area since 1982. While her group is one that meets physically, rather than virtually, she says that any kind of support network can be helpful to owners weathering a crisis with their pets.

“It’s so important for people to find some kind of validation for what they’re feeling, whether it’s online, one-on-one counseling, books, or support groups,” she says. “Now there are wonderful resources, and people don’t have to get through it alone.”

Benefits of community

One benefit of online groups commonly mentioned by participants is the feeling that they become part of a community or family. Sharing a common challenge can be a powerful bond.

Andrea Barnhart of Albany, New York, found the Canines in Crisis cancer board when her dog, Patches, began battling lymphoma and leukemia. “These people truly understand what I’m going through because they are experiencing the same emotions,” she says.

Brenda Osbourne of Owasso, Oklahoma, joined the Orthodogs group when one of her seven dogs required knee surgery.

“It was like being brought into a big extended family, and the warmth and the caring was so heartfelt,” she says. “It felt so good to be sharing what is a very frightening journey with so many other people who had not only been through it but were so willing to help you get through it.”

Osbourne became so involved in the group that she became an official moderator – a member with administrative rights who polices the message posts, keeping an eye out for people who ignore the basic rules (no profanity, no personal attacks, etc.) or have less-than-altruistic agendas, such as pushing commercial “miracle cures.” Osbourne now spends a good part of each day reviewing posts and answering questions, squeezing out the time despite her demanding career in cancer research.

In some cases, the feeling of family extends beyond the computer. In March, a group of people on the Orthodogs message board pooled resources to help a financially challenged member afford surgery for her dog. And the members of a group known as Deaf Dogs hold yearly get-togethers around the country.

“I thought (that) was amazing,” says Monica Mansfield of Ancramdale, New York, who joined the group two years ago when she became interested in adopting a deaf puppy. “It is wonderful to get to meet some of the friends you’ve made online in person. I’ve been to two different Deaf Dog picnics and plan on attending many more.”

No stupid questions

Many newcomers can be hesitant about posing questions on these online boards, worrying that their inquiries are inane or redundant with earlier message posts. But most find their concerns to be unfounded.

“I wondered what they would think of another newbie asking the same dumb questions they’d heard a million times,” says Tamie Adams, an Alabama dog owner who found the Orthodogs group while researching ligament repair options for Brodie, one of her two Rhodesian Ridgebacks. “So I introduced myself and then proceeded to read, and read, and read, without posting very often. (But) as I became familiar with the other people who posted, I was amazed at how warm and caring they were to everyone.”

“I think it is a continual ‘passing of the torch’ in online groups,” says Mansfield. “Almost everyone starts as a newbie and is there for answers to their questions and to learn from the people who have more experience. Then they start becoming comfortable enough to start answering other peoples’ questions.”

Dr. Mininni says this give-and-take process can be very helpful to group participants.

“It’s important that you feel like you matter to others,” she says. “If you are both getting advice and giving it, and people are appreciative of that, those are multiple ways you’re helping your psyche.”

Advice and research

In addition to seeking the mental and emotional support offered by these groups, many owners also use them to compare notes, discuss new research and information, and give advice. Some turned to the groups in frustration after their veterinarians fell short in providing them details, or when they believed their vets couldn’t or wouldn’t provide information about adjunct therapies such as herbal remedies.

“Good grief, my surgeon didn’t give us squat!” says Adams. “I had researched herbs and supplements, but I had to get all the dosage information from (the group). I also got all of my pre-op and post-op information from the things that other people’s vets had told them.”

Paola Ferraris, of Milan, Italy, who also serves as a moderator for the Orthodogs group, says that people often appreciate hearing about the range of issues that can affect dogs before and after surgery.

“Comparing notes and reactions of the dogs post-op and pre-op can be useful,” she says. “In some cases, issues discussed – such as pros and cons of (a certain) clinic, or breed-specific (problems) that vets rarely mention – have helped people discuss all options with their surgeons, or made others aware of potential reactions and side effects of treatments.”

Members may also suggest alternative therapies or procedures that other owners hadn’t considered or even known about. “I’d have to say that if I weren’t part of this group I probably would never have explored holistic approaches or using natural herbal remedies in certain cases,” says Osbourne.

Indeed, reading posts on the Orthodogs board before Lucky’s surgery prepared me for some of the physical challenges that could plague her afterward, including constipation – something our vet didn’t mention despite our extensive consultations. It also clued me in to the potential of horsetail grass as a supplement to help speed bone healing.

Sometimes, there’s so little data out there that only talking to someone facing the same challenges can help. Monica Mansfield says the Deaf Dogs board was an invaluable resource for obtaining real-world information instead of theoretical feedback.

“There are so many things that I learned from the group that you can’t learn anywhere else,” she says. “Many vets don’t have much deaf-dog experience, since deaf puppies are routinely euthanized or culled. Also a lot of the parent breed clubs are against the placing of deaf dogs or puppies, so there is not much information to be gotten from them.”

The information provided can be more than anecdotal. It’s not unusual to find message board members posting links to recent veterinary journal publications, studies, press releases, or newspaper and magazine articles. That’s yet another way members can deepen their understanding of the challenges they and their dogs are facing.

A few drawbacks

Despite the benefits they offer, message boards must be consulted with prudence. The biggest risk of using message boards is using poor information and putting your pet at risk. Few people deliberately post incorrect suggestions, but they may not get all their facts straight. In addition, the people who are the most prolific posters aren’t necessarily the ones with the best information, which can make it tough to decide when to accept ideas and when to break out that proverbial grain of salt.

“New people don’t know who to listen to,” says Osbourne. “With a group the size of Orthodogs, new people tend to get a lot of responses and since they’re usually just beginning their journey, they don’t know how to sort out the good advice from the bad. I think it can be a little overwhelming sometimes.”

If you obtain any medical advice or information from a message board, run it by your vet before putting it into practice. Herbs and supplements may interfere with medications or affect dosages. Changing a diet can stress an ill dog if it’s not done correctly. And rehabilitation protocols vary widely. Your vet might have a very good reason for, say, allowing your dog a short daily walk post-surgery while requiring that another dog remains completely immobilized.

It’s also wise to verify what you read through independent, reliable sources rather than taking one person’s posts as gospel. When I read a recommendation about horsetail grass as a bone-healing supplement, I verified that claim through Drug Digest (drugdigest.org), a consumer health and drug information Web site; the Food and Nutrition Information Center (nal.usda.gov/fnic/index.html) at the National Agricultural Library; and Greg and Mary Tilfords’ definitive reference, Herbs for Pets.

Some of the problems with online message boards are more social than serious. One common complaint is that it’s sometimes difficult to interpret the emotions behind the typed word. “The worst drawback is not being able to get the ‘tone’ behind the posts,” says Mansfield. “It’s very hard to tell if someone is being sarcastic, serious, kidding, or angry just by their words. I think that a lot of misunderstandings happen that way, on all the groups.”

“It’s e-mail, which tends to be a very impersonal way to communicate,” agrees Osbourne. “Messages can be misinterpreted or somebody’s sense of humor doesn’t quite come through and it can cause problems.”

Also, you should be aware that your vet may not be completely supportive of your involvement in message boards, especially if what you read conflicts with his advice or protocols.

“I think some vets consider the list a big pain,” says Ferraris, “(because) people start comparing prices for surgery, rehab options, therapies, and post-op protocols.”

Maximize the resource

The best way to approach message boards is to view them as research and support tools, rather than replacements for your veterinarian. Don’t accept at face value the information you read, and keep your vet in the loop at all times when it comes to medical decisions, including complementary and alternative options. Talk to your vet about message-board questions and concerns with a collaborative mindset, rather than thinking combatively.

“I’ve told my vet I participate in the group, (and) she supports it,” says Adams. “I just tell her my game plan after weighing all the input from the group and my own research, and get her feedback.”

And don’t discount the value of the boards’ social support when you’re dealing with a crisis.

“Numerous studies show that feeling connected to others and using that care when needed can decrease sadness, anxiety, loneliness, and feelings of helplessness,” says Dr. Mininni.

“I’m so thankful for the message boards,” says Barnhart. “There have been suggestions made by other visitors that have made a big difference for Patches . . . medicines, supplements, books to read, diets, you name it. And the support and comfort that I have gained have been amazing.”

-C.C. Holland is a freelance writer in Oakland, California, and regular contributor to WDJ. Her dog, Lucky, is recovering well from TPLO surgery.

Rage Syndrome in Dogs

RAGE SYNDROME: OVERVIEW

1. Document your dog’s episodes of unexplainable, explosive aggression so you can describe all the details to a trainer/behaviorist, including all environmental conditions you can think of.

2. Seek the assistance of a qualified, positive dog trainer/behavior consultant. Take your documentation with you on your first visit.

3. Be safe, and be sure others are safe, around your dog.

The term “rage syndrome” conjures up mental images of Cujo, Stephen King’s fictional rabid dog, terrorizing the countryside. If you’re owner of a dog who suffers from it, it’s almost that bad – never knowing when your beloved pal is going to turn, without warning, into a biting, raging canine tornado.

The condition commonly known as rage syndrome is actually more appropriately called “idiopathic aggression.” The definition of idiopathic is: “Of, relating to, or designating a disease having no known cause.” It applies perfectly to this behavior, which has confounded behaviorists for decades. While most other types of aggression can be modified and reduced through desensitization and counter-conditioning, idiopathic aggression often can’t. It is an extremely difficult and heartbreaking condition to deal with.

The earmarks of idiopathic aggression include:

• No identifiable trigger stimulus/stimuli

• Intense, explosive aggression

• Onset most commonly reported in dogs 1-3 years old

• Some owners report that their dogs get a glazed, or “possessed” look in their eyes just prior to an idiopathic outburst, or act confused.

• Certain breeds seem more prone to suffer from rage syndrome, including Cocker and Springer Spaniels (hence the once-common terms – Spaniel rage, Cocker rage, and Springer rage), Bernese Mountain Dogs, St. Bernards, Doberman Pinschers, German Shepherds, and Lhasa Apsos. This would suggest a likely genetic component to the problem.

The Good News About Rage Syndrome

The good news is that true idiopathic aggression is also a particularly uncommon condition. Discussed and studied widely in the 1970s and ’80s, it captured the imagination of the dog world, and soon every dog with episodes of sudden, explosive aggression was tagged with the unfortunate “rage syndrome” label, especially if it was a spaniel of any type. We have since come to our senses, and now investigate much more carefully before concluding that there is truly “no known cause” for a dog’s aggression.

A thorough exploration of the dog’s behavior history and owner’s observations often can ferret out explainable causes for the aggression. The appropriate diagnosis often turns out to be status-related aggression (once widely known as “dominance aggression”) and/or resource guarding – both of which can also generate very violent, explosive reactions. (See “Eliminate Aggressive Dog Guarding Behaviors,” WDJ September 2001.)

An owner can easily miss her dog’s warning signs prior to a status-related attack, especially if the warning signs have been suppressed by prior physical or verbal punishment. While some dogs’ lists of guardable resources may be limited and precise, with others it can be difficult to identify and recognize a resource that a dog has determined to be valuable and worth guarding. The glazed look reported by some owners may also be their interpretation of the “hard stare” or “freeze” that many dogs give as a warning signal just prior to an attack.

Although the true cause of idiopathic aggression is still not understood, and behaviorists each tend to defend their favorite theories, there is universal agreement that it is a very rare condition, and one that is extremely difficult to treat.

Idiopathic Aggression Theories

A variety of studies and testing over the past 30 years have failed to produce a clear cause or a definitive diagnosis for idiopathic aggression. Behaviorists can’t even agree on what to call it! (See The Evolving Vocabulary of Aggression, below.)

Given the failure to find a specific cause, it is quite possible that there are several different causes for unexplainable aggressive behaviors that are all grouped under the term “idiopathic aggression.” Some dogs in the midst of an episode may foam at the mouth and twitch, which could be an indication of epileptic seizures. The most common appearance of the behavior between 1-3 years of age also coincides with the appearance of most status-related aggression, as well as the development of idiopathic epilepsy, making it even impossible to use age of onset as a differential diagnosis.

Some researchers have found abnormal electroencephalogram readings in some dogs suspected of having idiopathic aggression, but not all such dogs they studied. Other researchers have been unable to reproduce even those inconclusive results.

Another theory is that the behavior is caused by damage to the area of the brain responsible for aggressive behavior. Yet another is that it is actually a manifestation of status-related aggression triggered by very subtle stimuli. Clearly, we just don’t know.

The fact that idiopathic aggression by definition cannot be induced also makes it difficult to study and even try to find answers to the question of cause. Unlike a behavior like resource guarding – which is easy to induce and therefore easy to study in a clinical setting – the very nature of idiopathic aggression dictates that it cannot be reproduced or studied at will.

Rage Syndrome Treatment

Without knowing the cause of idiopathic aggression, treatment is difficult and frequently unsuccessful. The condition is also virtually impossible to manage safely because of the sheer unpredictability of the outbursts. The prognosis, unfortunately, is very poor, and many dogs with true idiopathic aggression must be euthanized, for the safety of surrounding humans.

Don’t despair, however, if someone has told you your dog has “rage syndrome.” First of all, he probably doesn’t. Remember, the condition is extremely rare, and the label still gets applies all too often by uneducated dog folk to canines whose aggressive behaviors are perfectly explainable by a more knowledgeable observer.

Your first step is to find a skilled and positive trainer/behavior consultant who can give you a more educated analysis of your dog’s aggression. A good behavior modification program, applied by a committed owner in consultation with a capable behavior professional can succeed in decreasing and/or resolving many aggression cases, and help you devise appropriate management plans where necessary, to keep family members, friends, and visitors safe.

If your behavior professional also believes that you have a rare case of idiopathic aggression on your hands, then a trip to a veterinary behaviorist is in order. Some dogs will respond to drug therapies for this condition; many will not. Some minor success has been reported with the administration of phenobarbital, but it is unclear as to whether the results are from the sedative effect of the drug, or if there is an actual therapeutic effect.

In many cases of true idiopathic aggression, euthanasia is the only solution. Because the aggressive explosions are truly violent and totally unpredictable, it is neither safe nor fair to expose yourself or other friends and family to the potentially disfiguring, even deadly, results of such an attack. If this is the sad conclusion in the case of your dog, euthanasia is the only humane option. Comfort yourself with the knowledge you have done everything possible for him, hold him close as you say goodbye, and send him gently to a safer place. Then take good care of yourself.

The Evolving Vocabulary of Aggression

Different behaviorists and trainers have used and continue to use different terms for what was once commonly known as “rage syndrome.” The confusion over what to call it is a reflection of how poorly understood the condition is:

Rage syndrome – This once popular term has fallen into disfavor, due to its overuse, misuse, and poor characterization of the actual condition

Idiopathic aggression – Now the most popular term among behaviorists; this name clearly says “we don’t know what it is”

Low-threshold dominance aggression – Favored by those who hold that idiopathic aggression is actually a manifestation of status-related aggression with very subtle triggers

Mental lapse aggression syndrome – Attached to cases diagnosed as a result of certain electroencephalogram readings (low-voltage, fast activity)

Stimulus responsive psychomotor epilepsy – Favored by some who suspect that idiopathic aggression is actually epileptic seizure activity

“Rage syndrome” is not the only aggression term that has undergone a metamorphosis in recent years. Even the way we look at aggression is changing. Where once each “classification” of aggression was seen as very distinct, with its own distinct protocols for treatment, it is becoming more widely recognized that most aggressive behavior is caused by stress or anxiety.

It is now generally accepted by the training and behavior profession that physical punishment should not be used in an attempt to suppress aggressive behavior. Rather, aggressive behavior is best managed by preventing the dog’s exposure to his individual stressors, and modified by creating a structured environment for the dog – through a “Say Please” or “Nothing in Life Is Free” program – and implementing a solid protocol of counter-conditioning and desensitization to reduce or eliminate the dog’s aggressive reaction to those stressors.

We also now recognize that aggressive dogs may behave inappropriately and dangerously as a result of imbalances in brain chemicals, and that the new generation of drugs used in behavior modification work help rebalance those chemicals. This is in stark contrast to older drugs, such as Valium, that simply sedated the dog rather than providing any real therapy. As a result, many behaviorists recommend the use of pharmaceutical intervention sooner, rather than later, in aggression cases.

Here are some of the newer terms now in use to describe various types of aggressive behavior:

Status-related aggression: Once called dominance aggression, a term still widely used. Status-related aggression focuses more on getting the confident highranking dog to behave appropriately regardless of status; old methods of dealing with dominance aggression often focused on trying to reduce the dog’s status, often without success.

Fear-related aggression: Once called submission aggression. A dog who is fearful may display deferent (submissive) behaviors in an attempt to ward off the fearinducing stress. If those signals are ignored and the threat advances – a child, for example, trying to hug a dog who is backing away, ears flattened – aggression can occur.

Possession aggression: Previously referred to as food guarding and now also appropriately called resource guarding, this name change acknowledges that a dog may guard many objects in addition to his food – anything he considers a valuable resource, including but not limited to toys, beds, desirable locations, and proximity to humans.

Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, is WDJ’s Training Editor. She is also author of The Power of Positive Dog Training, and Positive Perspectives: Love Your Dog, Train Your Dog.

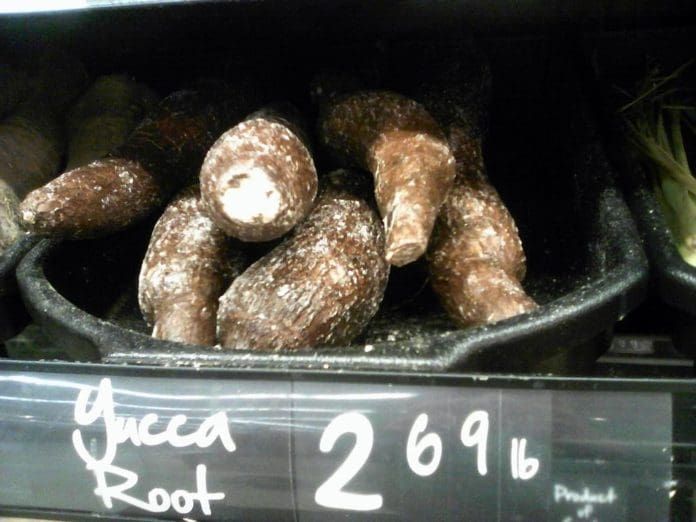

Yucca Root for Canine Arthritis Pain

[Updated March 29, 2018]

YUCCA ROOT FOR DOGS: OVERVIEW

1. Consider a yucca supplement for a dog with digestive problems that prevent him from properly utilizing his already top-quality diet, or for a dog with arthritis.

2. Use yucca for four days, and then discontinue for three days. An on-and-off-again schedule will help prevent irritation of digestive tissues.

3. Discontinue the use of yucca if the dog exhibits digestive upset such as vomiting and discuss this with your holistic veterinarian.

When valuable herbs gain momentous popularity in the mainstream marketplace they often show up as “buzz words” on various product labels. By market decree such herbs become not only popular, but stylish. After all, why would anyone want to buy an herbal cold remedy that doesn’t contain the mighty echinacea?

Usually when mass-market, celebrity herbs are born, oceans of research and published introspection soon follows to satisfy the curiosities of the consumer. We want to know why certain herbs keep showing up in the products we buy and use, and rightly so. Nevertheless, many herbs remain as ambiguous words on the labels of our favorite animal care products.

By San906 (Own work) [CC0]

Why is this so? Because manufacturers are largely prohibited, by federal regulations, to provide any tangible clues about the medicinal or nutritive attributes of the herb ingredients they list on their animal product labels.

One of the best examples of this is yucca – a succulent, cactus-like member of the lily family that inhabits desert areas and garden landscapes throughout America. Anyone who has studied natural dog and cat food labels, shampoo labels, and ingredient lists for livestock feeds has seen the name of this important plant food and medicine, yet very few of us can cite its intended purpose, much less a broad view of its holistic potential.

Yucca as a Nutritional Aid to Dogs

The description “nutritional supplement” really doesn’t fit yucca as well as the term “nutritional aid.” Although yucca root contains notable quantities of vitamin C, beta-carotene, calcium, iron, magnesium, manganese, niacin, phosphorous, protein, and B vitamins, this herb’s greatest nutritive and healing powers are chiefly attributable to a group of compounds collectively known of as saponins, which are found in the root of yucca.

Saponins are plant glycosides, which are characterized by their tendency to dramatically foam up when agitated with water, much like soap does. When ingested in very small amounts with food, saponins contribute a cleansing and penetrating action upon mucous membranes of the small intestine, which in turn helps with the assimilation of important minerals and vitamins through intestinal walls.

The results can be astounding. In studies conducted at Colorado State University, cattle fed small quantities of yucca root showed greater weight gain than those without. Other trials have concluded that chickens that are fed yucca have a tendency to lay more eggs, and dairy cattle tend to produce more milk.

Other research shows that when added to dog food, yucca can help reduce the emission of noxious odors in urine and feces. This finding comes from studies in which the chemical breakdown of urea (the body’s final by-product of digested proteins) were examined. The findings: anhydrous ammonia, which is largely responsible for the less-than-delightful odor of animal excrement is caused by a single microbial enzyme called urease, was inhibited when food supplements containing preparations of Yucca schidigera were fed. In the studies, fecal and urine odors were reduced by up to 56 percent in dogs and 49 percent in cats.

While the notion of less-offensive stool and less yard cleanup is attractive to many, the issue of excess urease should not go unchecked, as this kind of imbalance may lead to health problems that are much more serious than a soiled backyard.

Excess urea (and larger, more offensive stools) are often the result of a poor quality diet, where protein fillers (like soy meal) or cheap meat by-products cannot be efficiently broken down and eliminated during the digestive process. If left unchecked, this can lead to serious problems, such as urinary stones, kidney disease, arthritis, or chronic skin problems.

In other words, feed a balanced, natural diet, and excess fecal and urine odor shouldn’t be an issue in the first place.

My bottom line: yucca root can be helpful for optimizing a good quality diet that has been specially tailored to the needs of dogs that need added help with nutrient absorption. However, yucca really has no value as a supplement to lousy food.

Steroidal Effects of Yucca

Yucca root also possesses chemistries that add powerful medicinal activities to the veterinary herbalist’s goodie bag. Among these chemistries are sarsasapogenin, smilagenin, and various other compounds that are loosely known by the herbal/scientist community as “phytosterols.”

Herbalists theorize that phytosterols serve the body by stimulating and assisting the body in the use and production of natural corticosteroids and corticosteroid-related hormones. Unlike corticosteroid drugs such as prednisone, yucca is thought to work in concert with natural autoimmune functions of the body – actually supporting immune system functions as opposed to shutting them down.

It can be reasonably hypothesized that the natural, corticosteroid-like actions of yucca may play a role in the body’s natural production of growth hormones, which in turn may contribute significantly to the accelerated growth and production we see in animals that receive it in their food. And although this theory has not been established as “fact” by the scientific community, we know that yucca is very safe in the diet when fed in moderation and in a sensible manner.

What all of this means is that yucca can be a very useful natural remedy in the treatment of arthritis.

In a study conducted at the beginning of the twentieth century, yucca was found to bring about safe and effective relief (from pain and inflammation) to human arthritis patients when taken four times daily over a period of time. Although this study has been repeatedly discredited by the American Arthritis Foundation because of the contro-versial manner by which the study was conducted, the beneficial effects of yucca in humans and animals remain clearly validated in the minds of holistic practitioners who have repeatedly used it and witnessed positive results.

In my experiences with monitoring the therapeutic effects of yucca root in arthritic dogs, yucca can be very useful toward reducing inflammation of the knees and hips, especially when the herb is used concurrently with liquid extracts of licorice root (Glycyrrhizza spp.), alfalfa, and a liquid glucosamine supplement. Part of this may be attributable to the improved assimilation of glucosamine, another possible attribute of yucca’s amazing saponin constituents.

Undiscovered Values of Yucca Root for Dogs

Although scientists largely remain focused on the saponin constituents of yucca, it is obvious that there is much to discover about several other compounds within this plant. Native Americans used the roots, leaves, and flowers in a wide variety of applications, ranging from burns and digestive disorders to contraceptive applications.

A water extract (tea) of Yucca glauca (“small yucca” or “soapweed”) has been shown to have anti-tumor activity against a certain type of melanoma in mice. Its mechanism in this context is believed to stem from its polysaccharide constituents, not necessarily its steroidal saponins.

Perhaps most famously, yucca’s high saponin content has been widely exploited to make soap and shampoos.

A Few Words of Caution

Yucca root is classified by FDA and the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) as “Generally Regarded as Safe” (GRAS) for use in animal feeds and supplements. Yucca root powders, extracts, and other preparations can be used very safely in dogs and other mammals. Nevertheless, several controversies have been raised over the years concerning the safety of yucca’s saponin constituents.

Many of these concerns stem from cases of intestinal bloating or photosensitivity in livestock. Most of these events were triggered when too much saponin-rich, fresh alfalfa was fed while the plants were in bloom (alfalfa should only be harvested and fed prior to blooming).

There have also been reports of bloating and other digestive problems that have been attributed, at least in part, to cheap, fibrous, saponin-rich vegetable by-products (such as beet pulp) that are used in lieu of whole vegetables in commercial dog foods.

Then there are the numerous scientific studies in which animal subjects suffered digestive distress when they ingested (or were force-fed) isolated saponin compounds in chemical concentrations far exceeding than those naturally found in yucca root, or for that matter, any other herb. Such an experiment, in my mind, only proves that animals (and humans) shouldn’t eat soap.

Saponin is found in many of the vegetables we eat and frequently feed to our dogs (including yams, beets, and alfalfa sprouts), yet a few outspoken individuals insist that anything that contains saponin must be harmful. This is simply not true. Virtually anything will produce a toxic reaction if ingested in too much abundance, including herbs and vegetables.

Common sense rules here. Too much of virtually anything will likely cause some sort of toxic reaction, and yucca root is no exception. Remember this: Yucca is also known as “soapweed.” If used in excessive amounts over an extended period of time, yucca may eventually irritate the stomach lining and the intestinal mucosa. This in turn may cause vomiting. In fact, many of the Native American tribes of the southwest used yucca preparations to induce vomiting in cases of food poisoning. If vomiting or any other adverse effect is observed, discontinue use.

Yucca Dosage for Dogs

Although yucca has become a popular additive in pet foods, I do not feed foods that contain more than two percent yucca root on a daily basis unless a therapeutic purpose for a higher dose has been identified by a holistic pet care professional.

It is best to follow the manufacturer’s recommendations of yucca supplements that are formulated specifically for dogs. Yucca products vary according to their concentrations and added ingredients. If the product you buy does not have a suggested feeding amount on its label, then call the manufacturer or shop for a different brand.

As a food supplement for dogs with suspected malabsorption: Mix ¼ – ½ tsp. of dried, powdered yucca root (available at health food stores) to each pound of food fed each day. Feed on a schedule of four days on, three days off each week; this will help prevent overstimulation and subsequent irritation of digestive tissues that may otherwise occur with long term use.

As an anti-inflammatory and tonic for dogs with arthritis: Use a liquid tincture product that has been specifically formulated for use in dogs, and follow the manufacturer’s recommendations or the advice of your holistic veterinarian.

Alternatively, an alcohol-free liquid extract can be used. Again, buy one that is formulated for dogs and follow the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Greg Tilford is a well-known expert in the field of veterinary herblism. An international lecturer and teacher of veterinarians and pet owners alike, Greg has written four books on herbs, including All You Ever Wanted to Know About Herbs for Pets, (Bowie Press, 1999), which he coauthored with his wife, Mary.

Dog Ear Infection

DOG EAR INFECTION: OVERVIEW

1. Keep your dog’s ears clean. Use a gentle cleaning agent such as green tea, or a commercial product such as Halo’s Natural Herbal Ear Wash.

2. Use a pinch of boric acid to keep the dog’s ears dry and acidified.

3. Consult your holistic veterinarian in cases of severe or chronic infections; she may need to treat an underlying condition.

Chronic dog ear infections are the bane of long-eared dogs, swimming dogs, recently vaccinated puppies, old dogs, dogs with an abundance of ear wax, and dogs with allergies, thyroid imbalances, or immune system disorders. In other words, ear infections are among the most common recurring canine problems.

In conventional veterinary medicine, a dog ear infection can often be treated with oral antibiotics, topical drugs, or even surgery. The problem is that none of these treatments is a cure. Ear infections come back when the dog eats another “wrong” food, goes for another swim, experiences another buildup of excess wax, or in some other way triggers a reoccurrence.

Holistic veterinarian Stacey Hershman, of Nyack, New York, took an interest in dog ear infections when she became a veterinary technician in her teens. “This is a subject that isn’t covered much in vet school,” she says. “I learned about treating ear infections from the veterinarians I worked with over the years. Because they all had different techniques, I saw dozens of different treatments, and I kept track of what worked and what didn’t.”

Over the years, Dr. Hershman developed a program for keeping ears healthy and treating any problems that do arise, without the steroids and antibiotics usually dispensed by conventional practitioners. In addition, when she treats a dog with infected ears, she usually gives a homeopathic remedy to stimulate the dog’s immune system and help it fight the infection’s underlying cause.

“Ear infections are a symptom of a larger problem,” she says. “You don’t want to just treat the ear and ignore the rest of the body. You want to treat the whole patient.”

Dr. Hershman believes that many dog ear infections, especially in puppies, stem from immune system imbalances caused by vaccinosis, a reaction to vaccines. “The ill effects of vaccines,” she says, “can cause mucoid discharge in puppies. For example, it’s not uncommon for puppies to have a discharge from the eyes or to develop conjunctivitis after a distemper vaccine.”

Once a dog develops an ear infection, conventional treatment can make the problem worse. “Dogs are routinely given cocktail drugs, which are combinations of antibiotics, antifungal drugs, cortisone, or other ingredients,” she explains.

“After a while, you’ll go through 10 tubes, and your dog will develop a resistance. Then you’ll have to go to more powerful drugs to treat the recurring infection. In conventional veterinary medicine, chronic ear infections are considered normal. Dog owners are told they’re a fact of life, they’re never cured, they just keep coming back, and the best you can do is ‘manage’ them. My goal is to cure, not to manage.”

Dr. Hershman’s treatment for infected ears is not a cure by itself, but it’s a remedy that isn’t harmful, and it gives you an important kick-start in treating ears holistically. “That’s the approach that leads to a cure,” she says.

Note: If your dog develops an ear infection for the first time, or if his condition seems especially severe or painful, take him to see your holistic veterinarian, to rule out a tumor, polyp, or something else that requires veterinary attention.

Maintenance Ear Cleaning

Dr. Hershman’s healthy ears program starts with maintenance cleaning with ordinary cotton balls and cotton swabs. “This makes a lot of people nervous,” she says, “but the canine ear canal isn’t straight like the canal in our ears. Assuming you’re reasonably gentle, you can’t puncture the ear drum or do any structural damage.”

Moisten the ear with green tea brewed as for drinking and cooled to room temperature, or use an acidic ear cleanser that does not contain alcohol. Dr. Hershman likes green tea for its mildness and its acidifying, antibacterial properties, but she also recommends peach-scented DermaPet MalAcetic Otic Ear Cleanser or Halo Natural Herbal Ear Wash.

“Don’t pour the cleanser into the dog’s ear,” she warns, “or it will just wash debris down and sit on the ear drum, irritating it.” Instead, she says, lift the dog’s ear flap while holding a moistened cotton ball between your thumb and index finger. Push the cotton down the opening behind the tragus (the horizontal ridge you see when you lift the ear flap) and scoop upward. Use a few dry cotton balls to clean out normal waxy buildup.

Next, push a Q-tip into the vertical ear canal until it stops, then scoop upward while rubbing it against the walls of the vertical canal. Repeat several times, rubbing on different sides of the vertical canal. Depending on how much debris is present in each ear, you can moisten one or several cotton balls and use two or more Q-tips.

“You don’t want to push so hard that you cause pain,” she says, “but for maintenance cleaning using gentle pressure, it’s impossible to harm the eardrum. I refer to the external ear canal as an L-shaped tunnel, and I tell owners to think of the vertical canal as a cone of cartilage. People are always amazed at how deep the dog’s ear canal can go. I often have them hold the end of the Q-tip while I demonstrate cleaning so they feel confident about doing it correctly without hurting their dogs.”

If excessive discharge requires the use of five or more Q-tips, or if the discharge is thick, black, or malodorous, Dr. Hershman recommends an ear flush.

Dogster.com offers another protocol for cleaning your dog’s ears here.

Washing Out Debris from Your Dog’s Ears

Dr. Hershman realized that when an ear is not inflamed and not painful but full of debris or tarry exudates from a yeast or bacterial infection, flushing the ear makes sense. “If you don’t flush it out but keep applying medication on top of the debris,” she says, “you’re never going to cure the problem. But I also learned that flushing the ear is an art. You can’t simply fill the ear with otic solution and expect it to flow out by itself, taking all the debris with it. Because the dog’s ear canal forms a right angle, you just can’t get the liquid out unless you suction it gently with a bulb syringe or some kind of tube with a syringe attached.”

Flushing the ears, says Dr. Hershman, is one of the most important techniques you can learn for keeping your dog’s ears healthy. “They don’t teach this in veterinary school,” she says. “It’s something people learn by experience.”

When should the ears not be flushed? “If they’re painful, ulcerated, or bleeding,” she says, “or if there’s slimy, slippery pus in the ear or a glutenous, yeasty, golden yellow discharge. In any of these cases, flushing is not recommended. But if the ears are not inflamed and are simply waxy or filled with tarry exudates, flushing works well.”

The procedure begins with a mild, natural, unscented liquid soap from the health food store. Place a few drops of full-strength soap in the ear, then thoroughly massage the base of the ear. The soap is a surfactant, and it breaks up debris that’s stuck to the sides of the ear canal. From a bowl of water that’s slightly warmer than body temperature, fill a rubber bulb syringe or ear syringe, the kind sold in pharmacies for use with children or adults. Place the point of the syringe deep down in the soap-treated ear, then slowly squeeze the syringe so it releases a gentle stream of water.

“By the first or second application,” says Dr. Hershman, “you should see all kinds of debris flowing out. It’s like a waterfall. At the end of each application, hold the syringe in place so it sucks remaining water and debris up out of the ear canal. Then empty the syringe before filling it again.”

For seriously debris-filled ears, Dr. Hershman repeats the procedure three or four times, then she lets the dog shake his head before drying the ear with cotton balls and Q-tips. “I look for blood or debris,” she says, “and I check inside with the otoscope. If there’s still a lot of debris, I put more soap in, do a more vigorous massage, and flush it a few more times.

“An ear flush can be traumatic if the ear is inflamed,” she warns, “and occasionally there will be an ulcer or sore that you don’t know is there and it will bleed. That’s why you have to be careful about how you do this. You have to be vigorous but not aggressive. You don’t want to make the ear more inflamed, painful, or damaged than it was to begin with.”

After flushing the ear, Dr. Hershman applies calendula gel, a homeopathic remedy. “I put a large dab in each ear and ask the owner to do that once or twice a day for the next three days. The gel is water-soluble and very soothing. Calendula helps relieve itching and it stimulates the growth of new cells, so it speeds tissue repair.”

If the discharge in the dog’s ear is yeasty or obviously infected, Dr. Hershman skips the ear flush, instead using the following treatment.

Treating Dog Ear Infections

Careful treatment is required for infected ears and ears that are full of debris that resists even an ear flush. But what approach works best?

When Dr. Hershman began her veterinary practice, she met many dogs who wouldn’t let anyone touch their ears. “I knew that nothing I’d learned in vet school was going to help them,” she says, “so I thought back to all the treatments I’d seen over the years. The one that seemed most effective was a combination of boric acid and a thick, old-fashioned ointment that looks like pink toothpaste. I couldn’t remember its name, but I never forgot how it smelled – really peculiar, like burnt embers.”

The ointment was Pellitol, and as soon as she tracked it down, Dr. Hershman developed her own protocol for using it in combination with boric acid. Through groomers she had learned the importance of ear powders. “Like those powders,” she says, “boric acid dries and acidifies the ear. Yeast and bacteria are opportunistic organisms that die in a dry, acidic environment. They thrive where it’s moist, dark, and alkaline.”

Experimenting first with her own dogs and dogs at the animal shelter where she volunteered, she placed two or three pinches of boric acid powder in each infected ear unless it was ulcerated, bleeding, or painful. “Being acidic,” she explains, “boric acid might irritate open wounds. In that case, I would use the Pellitol alone. Otherwise, a pinch or two of boric acid is an effective preliminary treatment.”

Boric acid is toxic; note warnings on the label. It should not be inhaled, swallowed, or placed in the eye. Shielding the face is important and usually requires a helper, someone who can hold the dog’s head steady while protecting the eyes, nose, and mouth.

“I put the boric acid in and use my finger to work it deep into the ear canal,” she says. “If the dog has a very narrow ear canal, I gently work it down with a Q-tip.”

Next, she attaches the Pellitol applicator to the tube and squeezes the pasty ointment into the ear canal, applying enough pressure as she withdraws the tube to completely fill the canal. “I massage the ear,” she says, “especially around the base, then leave it undisturbed for an entire week. I learned this by trial and error. The Pellitol dries up within a day or two, but if you leave it undisturbed for an entire week, it removes whatever exudates are in the ear, whether they’re sticky, tarry, yeasty, or slimy pus. It just attaches to whatever’s there, dries it up, and everything falls out together.”

Pellitol ointment contains zinc oxide, calamine, bismuth subgalante, bismuth subnitrate, resorcinol, echinacea fluid extract, and juniper tar. “Zinc oxide,” says Dr. Hershman, “is a drying agent; calamine helps with itching and inflammation; bismuth is soothing and has antibacterial properties; resorcinol is used to treat dermatitis and other skin conditions; echinacea is antiviral and antibacterial; and juniper tar, like all tree resins, fights infection and makes the ointment very sticky. Once applied, it stays in place until it dries and flakes off, taking the ear’s debris with it.”

After a week, the ear should be much improved. “That’s when I use cotton balls or Q-tips to remove whatever’s left,” says Dr. Hershman. “I love this treatment because it works well, it doesn’t traumatize the ear, and it doesn’t antidote homeopathy.”

If Pellitol has an adverse side effect, it’s the product’s stickiness. “I tell people to protect their furniture for a day or two,” says Hershman. “The ointment will stick to anything it touches, and when you fill the ear, it can stick to the outside of the ear or the dog’s face. That excess will dry and fall off. You can remove it with vegetable oil, but leave the inside of the ear flap alone.”

Sometimes a second treatment is needed, and sometimes Dr. Hershman flushes the ear to complete the therapy.

While dog owners can successfully treat many ear problems with the foregoing program by themselves, don’t hesitate to bring your dog to your holistic veterinarian if he exhibits severe pain or discomfort, or if the ear problems recur. There may be an underlying issue that your holistic veterinarian can identify and treat.

Also, there have been cases in which the alternatives described here don’t work. If this happens, conventional treatment might be needed to defeat the bacteria infecting the dog’s ear. Dr. Hershman’s cleaning and flushing program can be used afterward for preventive maintenance.

A NOTE ON PELLITOL: Since this article was originally published, Pellitol stopped being manufactured under that name. The same product is still sold, but have your veterinarian contact your pharmacy to make sure you are getting the right product.

Ear Mites

Not every ear infection is an infection; sometimes it’s an infestation. Ear mites are tiny parasites that suck blood and fill the ear with waste matter that looks like black coffee grounds. The problem is most common in dogs from pet shops, puppy mills, shelters, or breeders with unclean environments.

Ear mites are species-specific, meaning that feline ear mites prefer cats’ ears and canine ear mites prefer dogs’ ears. Their bites ulcerate the ear canal, often leading to secondary infections.

How can you tell if your dog has ear mites? The definitive test is by microscopic examination, but Dr. Hershman describes two simple home tests. “Smear some ear debris on a white paper towel and wet it with hydrogen peroxide,” she says. “If it creates a brownish red stain when you smear it, you’re looking at digested blood from mites. In addition, most animals with ear mites have a positive ‘thump test.’ They vigorously thump a hind leg when you clean their ears because of intense itching.”

Ear mites are usually treated with pesticides, but there’s a safer, easier way. Simply put a few drops of mineral oil in each ear once or twice a week for a month.

Mineral oil has a terrible reputation in holistic health circles because it’s a petrochemical that blocks pores and interferes with the skin’s ability to breathe. But when it comes to fighting ear mites, these characteristics are a virtue. Mineral oil smothers and starves ear mites. Reapplying the oil twice per week prevents the growth of new generations.

Note: Herbal ear oils containing olive oil or other vegetable oils can be less effective in the treatment of ear mites, either because they contain nutrients that feed the tiny parasites or because they are not heavy enough to smother them.

For best results, use an eyedropper to apply mineral oil to the inside of the ear. Then use a cotton ball saturated with mineral oil to wipe inside the ear flap. Massage the entire ear to be sure the mineral oil is well distributed. Before each subsequent application, remove debris from the ear with cotton balls and Q-tips.

If mites have caused a secondary infection, follow the mineral oil treatment with Pellitol ointment and leave it undisturbed for several days.

Veterinary Help for Chronic Ear Problems

If you are unsure of your ability to clean or treat your dog’s ears, you can ask your holistic veterinarian to help you; with a little practice, you should be able to prevent ear problems and help your dog maintain a clean, dry, healthy ear on your own.

“These are simple, old-fashioned remedies,” says Dr. Hershman. “There is nothing high-tech about them. But after 30 years of treating ear infections, I’m convinced more than ever that they are the best way to treat canine ear infections.”

CJ Puotinen is the author of The Encyclopedia of Natural Pet Care and Natural Remedies for Dogs and Cats, both of which are available from DogWise. She has also authored several books about human health including Natural Relief from Aches and Pains.

Why You Should Switch Dog Foods Frequently

[Updated August 9, 2018]

Without a doubt, the most common question I am asked is “What kind of food should I feed my dog?”

Unfortunately, the answer is not simple. I try to teach dog owners to recognize the hallmarks of good quality foods, buy a bunch of them to try, identify a few that really suit their dogs, and then to rotate between three or four of the best. I suggest that they give their dogs one food for 2-4 months, and then switch to another food, and then another. Ideally, the foods are made by a few different manufacturers, and contain completely different protein sources, too.

Variability in Our Dogs’ Diets

All “complete and balanced” pet foods, even the ones made of the best ingredients, contain a premixed vitamin/mineral supplement. This is intended to ensure that the finished products contain a minimum amount of the nutrients deemed vital for canine health. This is needed because many of the nutrients present in the food ingredients are destroyed in the manufacturing process, and because it’s difficult (if not impossible) to find food sources of some nutrients, especially the trace minerals.

Despite the inclusion of the vitamin/mineral premixes, however, laboratory analysis of the finished pet food may reveal a wide range of levels for all the nutrients contained in the finished products. The Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO) provides guidelines for minimum levels for most nutrients, and maximum levels (for a few others). Within this basic framework, however, manufacturers have a lot of room to formulate their products to different levels, based on their own research, experience, and philosophies.

In fact, an interested dog owner can find quite a bit of variability in the nutrient levels in different pet foods – that is, if the maker will disclose this sort of minutiae. (The ones that won’t disclose the amount of any given nutrient in their formula aren’t worth dealing with, in my opinion.)

For example, the AAFCO nutrient profiles call for a minimum of 50 IU of vitamin E per kg of food, and a maximum of 1,000 IU/kg (based on dry matter, which excludes the moisture in the food from the calculations). Nature’s Variety reports that its “Prairie Brand Chicken and Rice Medley” contains 116 IU of vitamin E per kg of food (on a dry matter basis); Natura Pet Products reports that its “Innova” dry dog food contains 271 IU/kg of vitamin E.

Dogs Are What They Eat, Too

The point is, many of us have been conditioned to feed our dogs the same food, day in and day out. We are warned by food manufacturers and veterinarians alike that it is pointless and even possibly dangerous somehow to change a dog’s food. But a dog who eats the same diet every day can eventually become the living embodiment of the nutritional levels ever-present in his diet. To prevent nutrient toxicity, deficiency, or imbalance, the simple solution is to feed a variety of high-quality foods.

This just makes sense. If a company’s products are high in one nutrient, conceivably, after years of daily consumption of that food alone, a dog could develop problems associated with excessive levels of that nutrient. Years and years of feeding a food that is formulated to offer just slightly more than the minimum of another nutrient may result in a dog with a deficiency of that nutrient. Imbalances of nutrients that are best fed in certain proportions to each other (such as the Omega 3 and Omega 6 fatty acids) can also become entrenched in a dog’s body after years and years.

Smart Dog Food Switching

There are other reasons to change a dog’s food every few months or so. Switching from one source of protein to another occasionally can help prevent the development of food allergies or intolerances. It can also help prevent a dog from developing a stubborn preference for just one kind of food, which can be highly inconvenient.

When switching foods, spend a few days replacing the old food with the new in gradually larger proportions. This gives the dog’s digestive bacteria time to adjust to their new job, and should eliminate the gas or diarrhea that can sometimes accompany a sudden diet change.

Other than when you are switching from one food to another, it’s not a good idea to feed different foods at the same time. Your dog might enjoy a mix of half this and half that, but if he suddenly exhibits a digestive problem, it will be harder to track down the offending ingredients.

On a final note: Don’t hesitate to discontinue feeding any food your dog has a bad reaction to. No matter how much you trust its manufacturer, any product can suffer a dangerous manufacturing defect that could put your dog’s life at risk.

Download the Full May 2004 Issue

Join Whole Dog Journal

Already a member?

Click Here to Sign In | Forgot your password? | Activate Web AccessHome Remedies For Your Dog’s Skin Inflammation

IRRITATED SKIN RELIEF FOR DOGS: OVERVIEW

1. For fast, temporary relief of itchy skin that exhibits no change of appearance, liberally apply loose, soupy oatmeal or a cooled tea made with peppermint and/or lavender.

2. When itching is associated with minor redness, use a rinse made with herbs that speed healing and fight bacteria, such as chamomile, plantain, and/or calendula.

3. If your dog has open sores or scratches, use a rinse combining calendula and comfrey with sage, bee balm, thyme, and/or yarrow, to accelerate healing without harming beneficial microbes on the skin.

Winston, a four-year-old yellow Lab, is very happy. He got to go hiking with his human. But he is also itchy, and now he is chewing at little inflamed bumps on his chest and hind legs. Busting through underbrush in search of the ever-elusive cottontail, Winston picked up a few ticks. Luckily, his human always carries a fine-toothed flea comb when she walks in brush country with him, and she was able to remove the nasty blood suckers before they could dig in. Nevertheless, the ticks did get some bites in, leaving red, itchy, oozing bumps that may get infected if not treated.

Katie Bell, a 10-year-old Schnauzer, has different problems. She is itchy all the time, especially on her tummy and the insides of her haunches. Her skin there is pink, hot to the touch, and sometimes looks cruddy, even though she is as clean as a rambunctious little dog can be.

Katie Bell’s people know that her chronic condition is likely due to deeper problems – perhaps with diet, allergy, or autoimmune dysfunction. They are working toward finding a lasting resolution to Katie Bell’s distress, but need to find symptomatic relief for her in the meantime. And they wish to avoid, at all cost, the risky option of corticosteroid drugs.

If you live in the world of dogs, chances are you will be confronted some day with a dog suffering from some sort itchy-chewy skin ailment. Fleas, ticks, sunburn, mites, cuts, mosquitoes, cat scratches (those are especially fun to get), thorns, poison ivy, and especially allergies are bound to wreak havoc at some time or another, and you should be prepared for it.

Although most chronic skin problems like Katie Bell’s are secondary to deeper issues, such as food or flea allergies or perhaps sensitivity to exogenous chemicals in the environment, most skin problems can be temporarily relieved with proper use of topical remedies. And you probably don’t need to travel far to find one. Soothing, healing relief can be as close as the kitchen spice cabinet if your companion is bothered by an acute irritation, such as a “told you so” bite inflicted by the dog-harassed, queen feline of the house (my dog Willow insists it’s worth it).

Topical Home Remedies for Dogs’ Itchy Skin

One of the quickest ways to reduce inflammation of the skin and itchiness is by use of herbal astringents.

Astringents work their magic by quickly tightening skin and subcutaneous tissue, and thereby reducing inflammation and redness. A classic example of such an astringent is witch hazel extract, which can be purchased in a clear liquid, distilled form at any drugstore. A dab or two of witch hazel applied by cotton ball can bring instant relief to angry flea or mosquito bites.

It is important to know that most commercial witch hazel extracts are made with isopropyl alcohol, a substance that is toxic if ingested in large enough amounts. This type of witch hazel should be reserved for uses where only a few dabs are needed (i.e., don’t rinse your dog with it). Better yet, look for witch hazel that is made with ethanol (grain alcohol, the type contained in consumable liquors) or vegetable glycerin, an edible coconut oil derivative that is used in natural soaps and cosmetics for its emollient, skin-soothing qualities.

Several choices of natural topical remedies are available at the pet supply store, too. For hot spots, irritations caused from a bandage or a rubbing collar, sunburned ears, or insect bites that are limited to just a few points on the body, you might try a spritz or two of Animal Apawthecary’s FidoDerm Herbal Spray at the affected areas. FidoDerm contains aloe vera and calendula to help promote healing, along with a nontoxic assortment of antibacterial and antifungal essential oils.

Alternatively, you might wish to go the homeopathic route, with a few drops of Animal Aid (available from Biomedrix, Inc.), which is a combination of 11 different homeopathic remedies plus aloe vera. Or you could try P15 Skin Relief by Newton Laboratories, Inc., which combines a dozen homeopathic remedies into a base of 15 percent alcohol.

Do these “shotgun approach” homeopathic combinations work? For an answer to that question I talked with Terri Grow, CEO and founder of PetSage, Inc., a retail catalog company that stocks hundreds of natural pet care products and offers classes on how to properly use them.

“My customers report that the Newton (P15 Skin Relief) product works especially well for chronic, itchy patches,” says Grow, “especially when given internally and applied externally simultaneously.” She says that the aforementioned Animal Aid product works better to speed healing of more acute issues, such as flea and insect bites. This makes sense to me as an herbalist; the formula is based with aloe vera, a time-proven healing agent.

All-Over Itchiness

If your dog’s itching is body-wide and nonspecific, you may need to consider a full body rinse, or a natural anti-itch shampoo. Keep in mind, however, that there are no stand-alone “cure-alls” out there, and most topical products are designed to address specific conditions.

For instance, “skin and coat” products that are based with aloe vera may work great for healing wet, runny sores and oozing bites, but may be too drying for dogs with dry, flaky skin. In those cases, you are better off with products that contain vegetable oils, collagen, and herbs that promote skin healing without stripping natural body oils from the hair follicles.

One choice is AvoDerm Collagen Spray from Breeder’s Choice. This product contains avocado oil and collagen P-10, both of which are known for their skin-conditioning properties. Unfortunately, as with many pet care products, the other ingredients of the formula are not listed on the label; word on the street, however, is that this product works pretty well.

A good shampoo can bring relief, too, but keep in mind that “squeaky-clean” may not be what your dog needs. One of the biggest problems associated with frequent bathing is that many dog shampoos do their job too efficiently, cleansing the skin and coat of the waxy oils that are needed to maintain supple, healthy skin.

Of course, as I mentioned before, you may not need to buy commercial products at all. The remedy you need might already be in your home kitchen or garden. The following are a few of my favorite home brewed topical remedies. For dogs with itchy skin that exhibits little or no change of appearance (it just itches!), try a liberal application of oatmeal. Yep, the stuff we eat for breakfast. Cook it into a loose, soup-like consistency, allow it to cool, take it and your companion outside, and drench him with it. Allow it to remain in his coat as long as possible, before rinsing or brushing out the residue.

Another option is to make a peppermint and/or lavender skin rinse. Alternately, rosemary can be used as well. Buy some bulk lavender herb or peppermint leaf (or combine both) at the health food store. Pack a large tea ball full of the herb, and steep it in a quart or two of near-boiling water until it cools. Then drench the pooch with the liquid. It will help his itching, and he will smell nice, too!

When itching is associated with minor redness, I use rinses that incorporate herbs with vulnerary (speed healing) and bacteria-fighting qualities. Daily skin rinses made of chamomile, plantain, or calendula (individually or combined) are all worthwhile choices. Again, completely soak the dog with the tea, and allow him to drip-dry.

If open scratches, scabs, or sores are visible, combine calendula and comfrey with sage, bee balm, thyme, and/or yarrow tea in equal proportions. This will accelerate the healing process and help inhibit bacterial infection without irritating the skin or interfering with the activities of beneficial microbes and ectoparasites – friendly bugs that help keep the skin healthy.

However, if your companion’s skin condition appears severe (the skin is flaky, red, and scratching or chewing is continuous), stronger astringents may be needed. A decoction of uva-ursi leaf, juniper leaf (a common landscape shrub), or rose bark (any variety will do), combined with calendula flowers, should serve well here. Here is one such formula:

Astringent/Healing Skin Rinse

Combine equal parts of the following fresh and/or dried herbs:

- Juniper or uva-ursi leaf

- Calendula flowers

- Peppermint leaf

Combine all of the herbs and place into a glass or stainless pot. Cover with water and bring to a gentle boil over moderate heat. Simmer for 10 minutes, then remove from heat and allow to stand until cooled. Strain the cooled fluid through a sieve. Then soak the dog’s skin and coat and let him drip-dry.

If your companion insists on licking the solution off, you can use the rinse as a fomentation. Wrap an old towel or cloth (preferably dye-free and unbleached) around the affected body parts, and then thoroughly soak the towel with the cooled solution. This prevents your pup from licking the solution off, and enables you to keep the solution on her for several hours.

When to Call the Vet

If an established bacterial infection is evident (swelling is elevated and hot/red, and sores are discharging pus), you need to call your veterinarian. If she happens to be holistic, she might consider the following regimen, which is used to boost immune system response to the infection while adding direct antibacterial intervention:

- Twice-daily internal doses of echinacea tincture, to boost the immune system, along with a twice-daily dose of Oregon grape tincture, to strengthen liver function and the body’s elimination of systemic waste materials and bacterial die-off.

- Twice-daily external applications of echinacea and Oregon grape (or organically farmed goldenseal powder, tincture, salve, or ointment at the sites of infection).

As you see, symptomatic relief for your dog’s itching may be at arm’s reach. Just keep in mind that chronic skin ailments are seldom skin-deep, and treating symptoms such as dry, itchy skin or hot spots with topical remedies alone will not amount to a curative therapy for deeper health issues. Most chronic skin issues are related to allergies, diet, or both. To find a lasting solution for your companion, talk to a holistic veterinarian who is familiar with issues of nutrition, allergies, and natural approaches to skin care.

Greg Tilford is a well-known expert in the field of veterinary herbalism. An international lecturer and teacher of veterinarians and pet owners alike, Greg has written four books on herbs, including All You Ever Wanted to Know About Herbs for Pets (Bowie Press, 1999), which he coauthored with his wife, Mary.

Advanced Dog Training Methods: How to “Fade” Prompts and Lures

FADE TRAINING LURES: OVERVIEW

1. Examine your training routines with your dog to identify where you use prompts.

2. Determine which prompts you are using appropriately in the early stages of training a new behavior, and which ones are candidates for fading.

3. Create a written training program for each prompt you’d like to fade. How will you go about it? What results do you expect?

4. Implement your prompt-fading programs. Keep a daily journal to monitor your progress. Celebrate each time the two of you succeed in fading your prompts from another behavior!

Old-fashioned trainers – those who use physical corrections as a moderate or significant part of their training programs – often criticize positive training, saying that “foodies” (positive trainers) have to bribe their dogs to get them to do things. This is a shallow, shortsighted view of a powerful, effective tool.

It’s true that in the beginning stages of positive training we do use treats, also known as lures, to show the dog what we want him to do. Some positive trainers also use visual signals and gentle physical assistance as “prompts” to communicate with the dog.

But in a good training program, as soon as the dog performs a behavior easily for a prompt or lure, the trainer proceeds to put the behavior on cue. A cue is the primary signal (or stimulus) you use to ask your dog to perform a behavior. When a dog performs a behavior on cue quickly, anywhere, and under a wide variety of conditions, the behavior is said to be under stimulus control.

Many novice dog owners never make it past luring and prompting. As long as they’re satisfied with that level of training, it’s perfectly okay that they will always have to point, clap, or use a treat to get their dogs to perform. It’s their relationship, and their choice as to how well and clearly they want to be able to communicate with their dogs.