[Updated December 18, 2018]

ANESTHESIA-FREE TEETH CLEANING OVERVIEW

1. If your dog’s teeth are tartar-encrusted, or if his gumline looks inflamed, schedule an exam with your vet. Make sure she is aware of all of your dog’s health issues, and ask for her treatment recommendations.

2. If your dog’s teeth need cleaning, but he has health problems that put him at risk for complications during anesthesia, ask your vet whether she will perform an anesthesia-free teeth cleaning. If she declines, make it clear that you will seek the services of a veterinarian who will provide the service.

3. This is not the time for bargainhunting. Whether or not anesthesia is used, be prepared to pay for appropriate supportive measures as needed: blood tests, IV fluids, antibiotics, and/or pain-relieving drugs. Any or all of these may be needed to maximize the safety and effectiveness of the procedure.

Most of us have seen signs or advertisements for “anesthesia-free teeth cleaning” for dogs and cats. To most people, this sounds like a good idea, especially if you have a really old dog, a dog with a heart condition, or any other dog you’d hesitate to put through general anesthesia.

The procedure can be a terrific service for some dogs, but only if rendered under the direct supervision of a veterinarian, if not by a veterinarian. Unfortunately, some vets don’t offer the service – often, because they don’t believe it’s necessary. This pretty much guarantees that some pet owners will seek out non-veterinary technicians who perform the procedure – illegally – in grooming shops or pet supply stores.

We suggest that dog owners who are concerned about the risks of anesthesia ask their own trusted veterinarians to provide dental cleanings without anesthesia – and to seek out another veterinarian who does provide the service if their own veterinarian does not or will not. Here’s why:

Teeth Cleanliness Means Dog Healthiness

Tartar-encrusted teeth are not just unattractive; they are absolutely dangerous to a dog’s health.

Just as with humans, tartar or calculus forms on a dog’s teeth when plaque – a combination of salivary proteins and bacteria – accumulates on the teeth and is not brushed or mechanically scraped away by vigorous chewing. And just as with humans, some dogs seem more prone to tartar accumulation than others. Some of this may be due to an inherited trait; it’s also thought that the chemistry in some dogs’ saliva seems to promote tartar formation.

However it happens to accumulate, the mineralized concretion acts as a trap for even more plaque deposits. Soon, the gums become inflamed by the plaque, and bacterial infections may develop. Yes, the dog will have bad breath and unsightly red gums. He may experience pain when he’s eating his food, playing with toys, or during recreational chewing. Chronic mouth pain can cause behavioral changes, including crankiness and sudden onset of “bad moods.” But even more serious dangers are lurking unseen.

When plaque deposits begin to form in proximity to and then, gradually, under the dog’s gums, the immuno-inflammatory response begins to cause destruction of the structures that hold the dog’s teeth in place: the cementum (the calcified tissue that covers the root surfaces), periodontal ligament (connective tissue that helps anchor the teeth), and alveolar bone (the bone that surrounds the roots of the teeth). As these structures are damaged in the inflammatory response “crossfire,” the teeth can become loose and even fall out.

A more serious danger is the bacterial infection and resultant inflammation in the gums, which can send bacteria through the dog’s bloodstream, where it can wreak havoc with the heart, lungs, kidney, and liver. Dogs with chronic health problems that affect these organs and dogs with immune-mediated disease are at special risk of experiencing complications due to periodontal disease. For this reason alone, owners of these dogs should be the most proactive in keeping their dogs’ teeth clean.

Fears Around Teeth Cleaning with Anesthesia

People whose dogs are in poor health, however, are often the most reluctant to schedule a teeth-cleaning. Most frequently, they cite the effects of anesthesia on their dogs’ already compromised health as their biggest concern. In many cases, though, there are more serious things they should be concerned about, because the fact is that the vast majority of dogs, even old ones, come through the anesthetic experience without peril, as long as the veterinarian provides appropriate supportive care. (See “What You Should Know Before Your Dog Receives Anesthesia,” WDJ November 2002, for a detailed article about the safest anesthesia protocols and how to insist on them for your dog.)

Far more perilous than properly administered anesthesia are the risks posed by dental “technicians” who are not well trained or are inexperienced, and who are working without the benefit of veterinary support or supervision.

Undoubtedly, some of the people who provide “anesthesia-free teeth cleaning” services outside of veterinarians’ offices are well-educated and experienced. Some may be former (human) dental hygienists or licensed veterinary healthcare technicians. Some do a terrific job.

But the fact is, no matter how talented or experienced or well-educated they are, if they are not working with a vet who will perform a complete physical examination of the dog before the procedure and provide care afterward (if needed), they are performing veterinary medicine without a license. And because their services are illegal, it’s not possible for a consumer to confirm their credentials or even have legal recourse if they injure or harm a client’s dog.

The Best Candidates for Anesthesia-Free Teeth Cleaning

Fortunately, some veterinarians now offer anesthesia-free dental cleanings in their clinics, in recognition of the fact that some dogs may be adversely affected by anesthesia, and yet would benefit from dental care. The best candidates include dogs with tartar-encrusted teeth who exhibit any of the following:

• Poor kidney and/or liver function (detected with a blood test)

• Congenital heart defects (including murmurs), impaired heart function (such as congestive heart failure) or arrhythmia

• A recent injury or infection of any kind (even skin infections, including “hot spots,” are good cause to delay scheduling any procedure that requires anesthesia)

• A history of seizures (some preanesthetic sedatives can lower the seizure threshold)

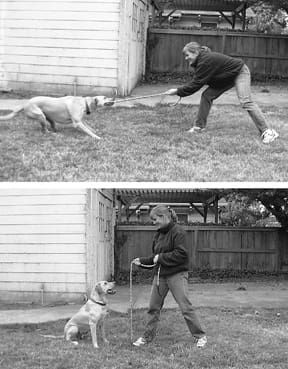

If your dog has one of the conditions listed here, or another health problem that concerns your veterinarian, he may be a good candidate for anesthesia-free teeth cleaning. But you should understand that the procedure is not a walk in the park; it can be hard on the dog, and the cleaning is necessarily less thorough than one conducted with the dog asleep.

“It’s so much easier to do a good job on a dog who is asleep,” says Jenny Taylor, DVM, founder and co-owner of Creature Comfort Holistic Veterinary Center in Oakland, California. “You get a vastly more thorough examination and a much better cleaning when the dog is unconscious.”

To do a good cleaning, the veterinarian or technician will need to spend long moments on each tooth – the cute ones in the front and the difficult-to-reach ones in the back. The outer surfaces (closest to the lips) are the easiest to reach and are always the most tartar-encrusted, but even the surfaces on the inside of the dogs’ teeth (closest to the tongue) should be examined and cleaned. This is tough to accomplish with even the most compliant dog.

Also, working without anesthesia may require the vet or technician to work without the benefit of the fastest and most effective tool in the teeth-cleaning arsenal: the ultrasonic scaler. Few dogs will sit still in the face of its noise and vibration, so the vet frequently can use only hand-held scalers. It can be difficult to manipulate the sharp tools with the required force to remove stubborn calculus without causing inadvertent injury to the dog’s gums, tongue, or lips, especially if he’s wiggling.

Finally, there is the dog’s experience to consider. A few happy-go-lucky dogs will comply with any procedure dreamed up by humans, as long as they get kisses and treats. But for some dogs, it’s torture. “People need to understand that working in the mouth can be a traumatic experience for some dogs,” warns Dr. Taylor. “We do a lot of things to keep the dog as comfortable as possible, but the procedure can cause some discomfort. Some dogs can tolerate a little pain and not hold it against anyone. But others can get upset no matter how tactful we are.”

For all of these reasons, even veterinarians who perform anesthesia-free teeth cleaning for certain dogs may promote an anesthetized procedure to the owners of dogs who are not at any special risk of complications from anesthesia. “Sometimes an anesthetized procedure is the kindest, safest thing for the dog,” says Dr. Taylor. “You have to consider each dog’s case individually and weigh all the factors: health, age, condition of the teeth, and temperament.”

Don’t Neglect Your Dog’s Teeth

In the best of all possible worlds, dog owners would provide appropriate home care to prevent their dogs from developing tartar buildup and gingivitis. (Some dogs go through their entire lives with sparkling white teeth, with absolutely no effort on their lucky owners’ part; we’re not talking about them!) For dogs who develop tartar buildup very quickly, daily brushing can go a long way to reduce (although, probably not eliminate) the need for professional cleanings.

For people who have concerns about professional teeth cleaning with anesthesia, then, prevention should be key. Maintaining your young, healthy dog’s mouth is largely a matter of daily discipline.

If your dog has already developed tartar accumulations, though, don’t despair. But don’t delay taking action, either, because tartar leads to gum disease which leads to systemic disease. Recent human health studies, in fact, have suggested that there may be a link between periodontal disease, heart disease, and other health conditions, and that gum disease may be a more serious risk factor for heart disease than hypertension, smoking, cholesterol, gender, and age. So get that dog to your vet’s office and map out a management strategy. It might take just one cleaning to get your dog back on a healthy track, enabling you to maintain his pearly whites thereafter.

Don’t Clean Without a Vet!

But in case we haven’t already said it clearly enough, don’t just have a groomer or technician clean your dog’s teeth in the back room of a pet supply store. A veterinarian should examine your dog before his teeth-cleaning appointment, and may want to give you antibiotics to give the dog a few days before the cleaning takes place and for a few days afterward. Even if a dog owner sought out a technician who was not working under a veterinarian’s supervision, this one thing could make the difference between life and death for some dogs.

Another reason why a vet exam is critical: She may judge your dog to be a poor candidate for any sort of teeth-cleaning, with or without anesthesia. If your dog has advanced periodontal and/or active infection in his gums, any sort of cleaning may be temporarily out of the question. He’ll need antibiotics to get the infection under control before dental work should proceed.

And if your vet judges your at-risk dog to be very near the end of his life, if he is very ill, or if the amount of gingivitis (inflammation of the gums) is relatively minor considering the amount of tartar present, she may suggest not cleaning the dog’s teeth after all. In these cases, often the vet will opt to treat the dog with an occasional dose of antibiotics to reduce the bacterial burden, and monitor the response. If the dog improves sufficiently, she may proceed with an abbreviated, gentle cleaning.

Dr. Taylor began offering anesthesia-free dental cleaning in her practice specifically to ensure that her clients who were worried about anesthesia wouldn’t just sneak off to a back-room technician for their dog’s dental care. “I want my clients to discuss their fears with me, so I can help them understand all of the ramifications of their decisions, and help them plan the most effective and safest course of treatment for their dogs,” she says. “If they really want the anesthesia-free service, I’m happy to provide it – along with any other needed support. This may include antibiotics, but it also includes flower essences, aromatherapy, and maybe even acupuncture to help reduce the stress of the cleaning.”

It’s a model we wish all veterinarians would emulate.

Unless They Work With a Vet, They Work Without a Net

In the United States, only licensed veterinarians, or certain healthcare workers who are under the direct supervision of a veterinarian, may legally clean your dog’s teeth. (“Healthcare workers” include licensed, certified, or registered veterinary technicians, veterinary assistants with advanced dental training, dentists, or registered dental hygienists; “under the direct supervision of a veterinarian” means with a vet in the same building, who will examine the dog and check the tech’s work.)

Some technicians allege that this is a matter of veterinarians protecting their revenue. They claim that teeth cleaning isn’t rocket science, and that an experienced technician can do as good a job or better than most vets. The vastly lower price they charge for the service, they say, encourages more pet owners to have their pets’ teeth cleaned more frequently. This is all true.

But because of the risks of harm that can be done by an unskilled or poorly educated technician – or even a skilled one without veterinary backup or supervision – we suggest making sure your dog’s teeth are cleaned in a veterinary clinic.

Inexperienced technicians, especially working on a wideawake dog, might not notice dental problems that need professional veterinary dental care, such as a fractured or loose tooth, extra or retained teeth that are causing orthodontic problems, or advanced periodontal disease. Dogs with the latter condition (especially small and tiny dogs) risk jaw fractures caused by weakened, diseased bone.

There are also plenty of non-dental health problems that a non-veterinarian may fail to notice, such as early signs of oral tumors, enlarged lymph nodes, or certain odors in the dog’s breath that can indicate other disease processes (sweet, fruity breath can indicate diabetes, and the odor of urea can indicate kidney failure). A vet can take a tissue biopsy or pull a sample for a blood or urine test if she notices one of these signs, thus diagnosing serious health problems in their earliest stages; of course, a technician working without a vet cannot.

The most likely problem that can be caused by a technician who has no veterinary supervision, however, is infection. Teethcleaning unleashes a storm of bacteria into the mouth and into the bloodstream. For dogs with cardiac problems and many other illnesses, this can be fatal – if not countered with preemptive as well as postoperative antibiotics, which are legally available only with a veterinarian’s prescription.

Recently, Oakland, California, veterinarian Jenny Taylor had a client bring her dog in for an emergency visit, admitting she had recently had her dog’s teeth cleaned by a technician, who suggested she get the dog to a vet for antibiotics immediately.

“I would have preferred that the tech had declined to clean the dog’s teeth until the owner got the dog on antibiotics,” Dr. Taylor says ruefully. “But at least the tech was competent enough to recognize a case where the dog really needed to get prompt follow-up care from a vet. By insisting the client follow up with a vet, he took the risk that the vet would report him; some might have just risked the dog’s health and kept their mouths shut.”

Nancy Kerns is Editor of WDJ.