Download the Full March 2011 Issue PDF

Only Human

I was casually reading an online article this morning from BayAreaParent DOG Gone It , thinking “Yeah, yeah, yeah, another sad failed dog adoption story.” You know, newlywed couple buys Labrador Retriever puppy, gets pregnant, doesn’t train the dog, dog is out of control, gets banished to the back yard when the baby comes, dog is miserable, owner gets pregnant again, blah, blah, blah…”

Then I got to the part where the owner said, “Norm threw the ball and Josie wandered toward it. I guess she got in the way, because all of a sudden Chance bolted towards Josie and very deliberately knocked her down the embankment.”

They ultimately contacted rescue and rehomed the dog, after concluding that they had adopted the wrong dog to start with, at the wrong time (“the Humane Society says to wait until children are 5 years old to adopt a dog”) and that Chance had purposely tried to harm their daughter.

I was so disturbed by this outrageous statement that I had linked to the article on my Facebook page. An interesting discussion ensued.

I started it off by saying, “First of all – they didn’t pick the wrong dog. They forgot to train the dog they picked. Second – they didn’t pick the wrong time – she wasn’t pregnant when they got Chance – they failed to make good use of the first year to train their dog. Third – I doubt the dog “very deliberately” knocked the baby off the cliff. Dad threw ball. Dog chased ball. Baby was between dog and ball. Crash. Bad throw, Dad!”

Yep, I was critical of the owners for their poor choices, and the first few FB responses took a similar view.

“Sad… it happens all the time.”

“People need to do their homework before getting a dog.”

“That’s exactly what I was thinking as I read the article.”

But then an interesting thing happened: some of my trainer friends started defending the writer of the article. At least, they said, the owners recognized they weren’t meeting the dog’s needs, and did the responsible thing by rehoming her.

“Chance’s owners finally did act responsibly and intelligently when they realized they were not up to having a dog.”

“I liked this article and how she took responsibility for not doing right by the dog.”

“The article was redeemed for me by her understanding of Chance’s misery and of the fact that her family had failed to meet the dog’s behavioral needs. (When was the last time you read the phrase “behavioral needs” in an article by a layperson??) ”

“I’m betting she gets a lot of very hostile response to this piece, and I admire her for accepting responsibility for the human screw-up.”

So there you go. We who are so good at forgiving our dogs for making mistakes sometimes have to be reminded to forgive other humans for doing the same. We are all, after all, only human. I’ll try to be better about remembering that next time.

(Multi-Dog Household Aggression and Fighting #2) Identifying The Triggers to Your Dogs Rage

We do know that aggression is caused by stress. With the very rare exception of idiopathic aggression – at one time called “rage syndrome,” “Cocker rage,” or “Springer rage” and grossly overdiagnosed in the 1960s and ’70s – aggression is the result of a stress load that pushes a dog over his bite threshold.

It’s often relatively easy to identify the immediate trigger for your dogs’ mutual aggression. It’s usually whatever happened just before the appearance of the hard stare, posturing, growls, and sometimes the actual fight.

When you have identified your dogs’ triggers, you can manage their environment to reduce trigger incidents and minimize outright conflict. This is critically important to a successful modification program. The more often the dogs fight, the more tension there is between them; the more practiced they become at the undesirable behaviors, the better they get at fighting and the harder it will be to make it go away. And this is to say nothing of the increased likelihood that sooner or later someone – dog or human – will be badly injured.

For more details and advice on modifying dog aggression, purchase Whole Dog Journal’s ebook, Approaches to Modifying Dog Aggression.

Bringing It All Back Home

My husband has kind of an obscure occupation. He’s a steel detailer; he creates detailed drawings of structural steel pieces for companies that fabricate the pieces and erect buildings out of them. His father learned the trade as a young man in the 1950s, and, early on, practiced his profession in a shirt and tie in the highrise offices of titans of the American steel industry. Late in his career, as an independent contractor for smaller steel fabrication companies, my father-in-law worked at a drafting table in his home and sent his drawings – in the form of thick, heavy rolls of paper – to his clients via FedEx. It was during this phase of his career that he taught the trade to my husband, who, today, uses a home computer to create the “drawings” and send them instantaneously to his clients via email.

288

The world is changing. I get it.

Sometimes it feels as if it’s changing far too quickly. My husband often receives email messages from people in India and China, offering to do his job for less money. These messages suggest that he could make a good living just by sharing his contracts with workers who will earn less than he does. If he finds the jobs and shares them, the emails hint, he won’t have to “work” at all.

But my husband likes his work, and these emails aggravate him no end.

I received an email this morning, forwarded from a friend who manages a pet food company. I gather that my friend is feeling just like my husband. “Dear Sir or Madam,” said the email. “We have a new freeze drying factory, Tianjin Ranova Petfood, in Tianjin, China. Do you have time to visit us? We got ISO 9001 and ISO 22000 (HACCP) certified. Please see the attached pictures of freeze dried Pet Treats and prices. The prices have already included costs for irradiation. Are you interested in these products?

I am looking forward to hearing from you.

Thank you and best regards.”

I wrote back to my friend, joking about how lucky she is to have such a good opportunity to buy irradiated pet treats from China! It was gallows laughter, though. She responded gloomily, “I get these emails daily. How many U.S. companies are already selling these treats? And then my clients complain because ours are too expensive!”

I never studied business. But I’ll never understand how common food ingredients can be shipped halfway across the planet and sold for half the price of domestically grown and processed ingredients. It certainly begs the question of the quality, freshness, and purity of the product.

I know what kind of products my friend’s company sells. They are top of the line. She can tell you the provenance of every piece of meat in her plant. But will her business survive this sort of pressure? And has the maker of your dog’s food and treats resisted it?

Frequently Asked Questions

LISTED BY COMPANY

I would like to know if you investigated Orijen dog food. I did not find it listed as one of Whole Dog Journal’s approved dry foods of 2011. Yet I noticed it pictured on the front page.

Janet Jaob

In the February issue with the approved dog foods, I see on the cover a bag of Orijen dog food (which we use), but I don’t see it in your approved list. What is your opinion of this food? Is it not good?

Denny Mosesman

We have been feeding our dog Chicken Soup for the Dog Lovers Soul for a couple of years and he seems very happy with it. Last year, that food was on your recommended list, but in the February 2011 issue, it was not. Is there a problem of any sort with the company? We try to do our homework, and are unaware of any problems with the food.

Ken Vasek and Susan Sims Pisano

I’ve just finished reading the newest edition of Whole Dog Journal and was surprised to see Taste of the Wild dog food omitted from you recommended list. I wonder if there is a reason it was omitted from the list?

Kathy Keating

To these and many more inquiries: The foods are listed alphabetically by the name of the company that makes them. Taste of the Wild and Chicken Soup are made by Diamond Pet Foods. Orijen (and Acana) are made by Champion Petfoods.

UNDISCLOSED MAKER

I was looking over the “Approved Dry Foods” list in the recent issue of WDJ and I was curious as to why Halo brand food did not make the cut.

Kristin Mason

I was wondering why Newman’s Own Organic Adult Dog Food didn’t make the list. The ingredients seem to match the list of what’s good and what’s not. Just wondering what I’m missing.

Patricia Klein

Both of the foods mentioned in these letters meet our selection criteria, except for one: the companies do not disclose their manufacturers. We list only those products whose companies disclose the manufacturing location.

As we discussed in our dry food review in February 2008 (the first year we asked the companies to disclose – for publication – the site of their manufacturing operations), there are a couple of legitimate reasons why a small company would not want to disclose its co-manufacturing partner. (There are also some disingenuous ones.) If you really like the products these companies make, and trust that the company will disclose pertinent manufacturing information about its products in case of a recall or other problem, you should by all means continue to support those products.

NEW TO US

I am curious as to why Nutri Life Pet Products didn’t make your list. Although I am no scientist, veterinarian, or similar, I have been diligent over the years in my selection of dry foods for my five beloved hounds and believed that Nutri Life produced a good quality food. As a lead volunteer for my greyhound rescue group, I have recommended this food to many former “Purina feeders,” so I hope I have not done this in error.

Jennifer Laughman

We’re sure there are many products (especially some that are made and sold in just a single state or a small area) that we’ve never reviewed. Please compare the product’s ingredient label to our selection criteria; you can easily see whether the product would measure up to the products on our “approved” list. If it meets the criteria we listed on page 5 (“Hallmarks of Quality”), it’s as good as the others on our list.

P&G?!

I fed my dog Natura’s Innova for many years. Last year my son and his wife put their two dogs on Innova. After a few weeks one of their dogs had symptoms of a food allergy. My son had found out that Natura was sold to P&G earlier that year. They switched to Dogswell and so did I.

Susan Lenahan

We won’t worry about P&G “ruining” Natura’s foods unless it actually happens, and it hasn’t happened yet. That said, some of the formulas have changed, but the formulation changes were in the works before P&G’s purchase, and none that we have seen reduced the quality of the products.

All companies tweak their formulas occasionally. We cut out and retain the ingredient lists from bags of foods that we feed so we can see what sort of shifts the companies make.

Whenever a dog reacts negatively to a food, it’s important to retain that ingredient list and make a note of the symptoms and date. If you switch foods a few times a year (and we think you should), you may be able to identify certain ingredients that your dog doesn’t tolerate well, which can help guide future purchases. Feeding just one food for long periods of time is also asking for trouble. Think about it; if it was ideal to eat the exact same diet every day, with no exceptions, year in and year out, don’t you think someone would be recommending this for humans?

We’ll answer more questions about our dry food review in the next issue.

What’s In a Dog’s Name?

The January issue of Whole Dog Journal featured “Say My Name,” an article by Pat Miller that explained the importance of teaching your dog to recognize and respond to his or her name. In a sidebar to that article, Pat also discussed the issue of naming (or renaming) your dog. And she announced a little contest for our readers, asking you to share the story of how you selected your dog’s name and why. Pat said she would select some winners and the “top three” would win a signed copy of her newest book, Do Over Dogs: Give Your Dog a Second Chance for a First Class Life.

Apparently, dog names are very important to our readers, too. We received more than 250 contest entries, via the U.S. mail and email, as well as through comments on the WDJ website (whole-dog-journal.com) and the WDJ Facebook page. (All of the Facebook and WDJ website entries can still be viewed online.) When we read them, we laughed, we cried, we felt like these stories ought to be a book! But picking a winner was difficult – kind of like adopting just three dogs out of a huge shelter full of terrific canine companions.

There was nothing scientific about Pat’s selection process; she simply chose the ones that touched her the most, with an admitted bias toward shelter and rescue dogs. Below are Pat’s three winners and three runners-up. Thanks to everyone who shared their funny, sweet, and memorable dog-naming stories.

“HOPE”

Kate Durket, Sutherlin, OR

Here is the story of my “do over” dog.

288

In 2004, after losing my beloved girl, Grace, I was adamant about finding a dog who needed a new chance. After many weeks of looking I was contacted by my vet, who told me about a six-month-old Shepherd-mix who had been severely beaten and left abandoned.

When I went to the shelter to see her I noticed that “Linda” (as she was then known) was being bypassed by all the people looking for dogs that day. When I finally stood in front of her kennel it was easy to see why. She was a mass of bruises and lacerations, and the only fur she had was on her head. I gently knelt down and without hesitation she came up to me and licked my hand. In that moment Hope was reborn. She joined her “sister” (my Cocker-mix, Faith) and has been a wonderful member of my family for the past six-plus years. And last year on Christmas Eve my third girl, Joyeux Noel was born.

My three girls, Faith, Hope, and Joy are ambassadors of love in my little town.

“SCORE”

Erin Saywell, Sykesville, MD

My pit-mix is named “Score.” Here’s his story:

I have a friend from an online message board who takes his dogs to a doggy daycare in North Carolina. My friend fostered and found homes for two Lab puppies who had been abandoned near a Dumpster near the daycare, so he was the one the daycare called the next time they needed to find a home for another abandoned pup.

It seems that a drug addict wandered into the daycare’s store area and stole $200 out of a donation jar. A few days later, he wandered back into the store. They told him to get out or they’d call the police. He asked them if they’d seen a puppy. With a lot of eye rolling, they told him to leave. Sure, he’s got a puppy . . . right! About an hour later, they found an eight-week-old puppy sitting on the sidewalk in front of the store. They scooped him up and called my friend, who took the puppy, of course.

My friend posted pictures of the puppy. I asked – half joking – if he’d like to donate the pup to my local assistance dog organization. He agreed readily, and we arranged for the new pup to come to Maryland.

I named him Score, both for his “old owner” and for his new life; he sure “scored”! He ended up washing out of the program because of his looks (too “pit bull”) and he stayed with me. He’s now a service dog demonstrator, a therapy dog, and an awesome flyball dog!

“LIBERTY”

Dawn Goehring, Gatlinburg, TN

157

On September 11, 2001, I needed a bit of love so I went to my local animal shelter. I was looking for a dog with good potential for becoming a trick dog. I was just getting started on training a group of dogs to perform together and I needed just the right dog to fit into my family.

When I got to the shelter I saw several dogs that would be great, but one caught my eye. She was a Beagle-mix, just circling in her cage. I knew this was not excitement, but stress. The closer I got, the faster she circled. I took her out. She jumped in my lap and proceeded to lick me all over. It was just the thing I needed on that sad day.

I took out some treats and played with her. I quickly found that she did the most beautiful stand on her back legs, like a statue! And because of the day, I thought of the Statue of Liberty. A patriotic name to remember the day and honor it. Liberty needed a job, as her neurotic circling was a major issue. But 10 years later she is one of my best working dogs, still curls up in my lap with kisses, and will always stand tall like the symbol she was named after!

Runners-up

Pat Miller selected the following three stories as runners-up in our contest, but of course these terrific owners are winners in their own right. What great stories!

“TOBY VAN HOGH”

Talitha Neher

288

When we were little, my grandmother used to unpin her hair, brush it until it crackled, and tell us she was a witch. Then she’d tell us the story of Little Dog Toby, who would bark! bark! bark! to scare away the hobbyahs that came of out the swamp at night to eat the Little Old Man and Little Old Woman. Unfortunately for Little Dog Toby, the Little Old Man (who hadn’t read Don’t Shoot the Dog!) thought Toby was just being obnoxious and came out with the scissors each night to cut off a body part and shut him up, starting with his ears.

Fast forward about 25 years, and I’m a veterinarian working with several local rescue groups. Thanks to a tolerant husband, my house is something of a halfway house for injured bully breeds. Usually they go on to long-term placements, but some of them stay. One of those is Toby.

Toby was anonymously relinquished to me after a home ear crop job went south. He came after a street-corner handoff, shaky and sick, ears crusted with blood, and dead tissue and cartilage hanging out everywhere. The lines of Sharpie ink were still visible on one side.

I got some fluids, antibiotics, and pain meds into him and took him to surgery to salvage what was left of his ears and relieve him of his testicles. I contacted Boise Bully Breed Rescue, made a report to Animal Control, and took him home for the night for observation. When I caught myself telling him that “Mommy would never let anyone hurt him like that again,” I knew he wasn’t going into rescue – and that meant he needed a name, preferably one that was pretty charming, since he would grow into an oversized pitty with a lopsided fighting crop.

I called my sister about him. “You have to call him Little Dog Toby!” she said. I also called my best friend from vet school, whose suggestion for a name was “Van Gogh!” Both names seemed to fit him, and he became Toby van Gogh.

He’s almost two years old now and embarking on agility classes. He’s going through a mouthy adolescent stage, but I can’t imagine life without him. I’ve attached a picture of his ears when he came to me and one of him now, hiking with his brother, “Stagger Lee.”

288

“ROSCO”

JoAnne Tuffnell

When our son and daughter-in-law brought home their beagle from the Humane Society, his name was “Midas.” They sat down and looked through lists of names, went online for good dog names, and talked with family members. They finally chose “Rosco.” We were all stunned at how quickly he responded to his name and knew their choice had been a good one.

A few weeks later we had tree men working in our woods. I started talking with one of them, and the conversation turned to dogs and rescue animals. I said our kids had just adopted a beagle named Rosco from the Hamilton County Humane Society. “They got Roscoe?” he asked. He proceeded to tell me that his relatives had adopted a dog from the city humane society, but he barked too much for their neighborhood; the relatives asked this man to take the dog, but it didn’t work out for him either, so he returned the dog to the relatives. The relatives then took him to the county humane society, pretending they had found him because they were too embarrassed to return him to the city’s pound. The county group took him in and placed him for adoption.

“But what does that have to do with Rosco?” I asked. The man said, “You said it’s a Beagle, right? And his name is Roscoe?” “Yes,” I answered, “But his name was Midas when my son and daughter-in-law got him. THEY named him Rosco.” He continued to talk about the dog and we compared notes and dates. Yes, the unbelievable is believable. Roscoe the Beagle became Rosco the Beagle. No wonder he learned his name so fast! And the lack of the letter “e” didn’t bother him one bit.

288

“ROGUE”

Debbie Schwagerman, Terrell, TX

Most of our dogs are rescues but we think they still deserve full “registered” names anyway! We pulled our latest rescue dog from a shelter that does not even adopt to the general public as our new “foster” dog. We like looking for fosters from this particular shelter because the dogs have such a small chance of getting out.

We were not looking to add a new dog to our permanent pack at all, but her slightly wild nature and sweet, snuggly personality caught us both off guard. We found ourselves unable to give her up when it came down to it. So, she became a permanent member of “The Ruff Mutt Gang” and was then named Ruff Mutt’s Caught Ewe Off Guard, aka “Rogue” (she’s a Border Collie, hence the “ewe” spelling).

Are Heartworms Developing Resistance to Preventatives?

In August 2010, representatives of the American Heartworm Society (AHS), the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC), and experts in the field of nematode resistance met in Atlanta. Their goal was to discuss the possibility of heartworms becoming resistant to “macrocyclic lactones,” the scientific name for the heartworm preventatives we know as Heartgard (ivermectin), Interceptor (milbemycin oxime), Revolution (selamectin), and ProHeart (moxidectin).

Dr. Everett Mobley, a veterinarian who practices in Missouri, wrote about this issue in his “Your Pet’s Best Friend” blog in May 2009. He says that he first began noticing an increase in the number of dogs in his clinic who tested positive for heartworms despite being on year-round heartworm preventatives in 2006. He learned that other veterinarians were reporting similar experiences, and that “These reports come from the Mississippi valley, starting about 100 miles south of St. Louis, and getting worse as one goes south.”

Experts dismissed these reports for a long time as being due to “client noncompliance,” that is, owners failing to give the preventatives to their dogs 12 months a year. It was not until April 2009 that they began to say, “We know that something has changed, but we don’t know what it is. There is a problem, but the underlying cause has not been determined.”

The issue was a primary topic of discussion at the American Heartworm Society’s 2010 Triennial Symposium held in April. A landmark initial study was presented that evaluated heartworm microfilariae in different regions of the Mississippi Delta. The study revealed differences in sensitivity of the samples to macrycyclic lactones. Separate experiments revealed genetic variability of heartworms in different geographic locations, which could potentially be associated with varying responses to the drugs.

Recommendations

The AHS and CAPC issued a statement in November regarding the findings of the meeting in Atlanta, acknowledging the problem and calling for further study. They believe that any heartworm resistance is geographically limited (presumably to the Mississippi valley) at this time based on credible reports of lack of efficacy. They recommend that pet owners continue to give preventatives year-round, following label directions, as they continue to be effective for the vast majority of dogs. There is no evidence that higher doses or more frequent dosing would increase protection. They also recommend yearly heartworm testing for all dogs, even if they have been kept on preventatives.

In the past, we have recommended that people might safely extend the time between doses of heartworm preventatives to six weeks, and decrease the dosage when using Interceptor, based on the efficacy studies that were done when the FDA approved these drugs. It is safer to administer preventatives monthly and to give the full label dosage. Following these steps will also ensure that, should your dog become infected, the product manufacturer’s guarantee will be honored and treatment costs will be covered. (Manufacturers will guarantee a product only when purchased from a vet.)

We still question the need to give preventatives year-round in cold climates, where mosquitoes cannot survive during the winter. The heartworm life cycle requires the larvae to spend time inside a mosquito in order to develop into adults; without mosquitoes, there is no risk of infection. In warm climates such as the southern half of the U.S. (below the 37th parallel), give heartworm preventatives year-round. This is also necessary to avoid voiding the manufacturers’ guarantees.

If you choose not to give heartworm preventatives year-round, keep in mind that these drugs work “backward,” killing larvae that may have infected your dog in the previous month. Give the last dose after temperatures have dropped, and start them up again a month after your area warms up. If temperatures remain above about 45 to 50 degrees, day and night, you should give your dog monthly heartworm preventatives.

Keep in mind when testing for heartworms that it takes at least six months following exposure before a dog will test positive. This interval may be increased if the dog is being treated with heartworm preventatives during this time. The AHS now recommends that three consecutive negative tests, each six months apart, may be needed before we can feel confident that a dog is not infected with heartworms.

Research into possible resistance of heartworms to current medications is ongoing in a number of universities and other centers in the United States, Canada, and Italy. We’ll keep you updated.

– Mary Straus

New Treatment for Pituitary-Dependent Cushing’s Disease

A surgical procedure used on humans to remove brain tumors that cause Cushing’s disease is now becoming available to dogs, thanks to collaboration between a human neurosurgeon, a veterinary endocrinologist, and a veterinary surgeon in the Los Angeles area.

288

Cushing’s disease (hyperadrenocorticism, or HAC) is an adrenal disorder common in middle-aged and older dogs, affecting an estimated 100,000 dogs per year in the U.S. It occurs when the body produces too much cortisol, causing increased appetite and thirst, skin problems, and muscle weakness. Cushing’s can also predispose dogs to other conditions such as diabetes, pancreatitis, and infections.

There are two types of Cushing’s disease: adrenal and pituitary. The pituitary form is the most common, accounting for about 85 percent of cases. Pituitary-dependent Cushing’s is caused by a small, usually benign tumor of the pituitary gland, which leads to overproduction of the hormone ACTH, which in turn triggers the adrenal glands to overproduce cortisol.

Because these tumors have been considered too difficult to remove, pituitary Cushing’s is managed with medications that suppress the production of cortisol. This treatment can relieve symptoms, but cannot cure the disease, and the treatment requires careful monitoring to ensure that cortisol levels don’t get too low. The average life expectancy for dogs with pituitary-dependent HAC is about 30 months, with younger dogs living longer (4 years or more). Many dogs ultimately die or are euthanized due to complications related to Cushing’s disease such as neurological problems, pulmonary thromboembolism, diabetes mellitus, or infection.

Human research into a new type of surgical imaging device is being done at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles. Recently, veterinary endocrinologist Dr. David Bruyette (DVM, DACVIM) and veterinary surgeon Dr. Tina Owen (DVM, DACVS) from VCA West Los Angeles Animal Hospital contacted the neurosurgeon who had been studying the use of a scope (called a VITOM) and asked if he would investigate whether the device could be used to perform pituitary surgery in dogs. After looking into it, the neurosurgeon recognized that this device would be ideal for dogs, and agreed to show Dr. Owen how to perform neurosurgery to remove pituitary tumors.

The surgery is done by creating a tiny hole in the back of the mouth in order to enter the skull at the base of the brain and remove the tumor. The VITOM, also called an exoscope, displays the area on a large, high-definition monitor, magnified up to 12 times its actual size. The tool makes the procedure easier and safer, but it still requires considerable skill to be able to do such intricate surgery.

I spoke with Dr. Bruyette about the results so far. Dr. Owen has performed the procedure on 15 dogs and two cats. One dog died during the surgery, and two others died after treatment for unrelated reasons; the rest are doing well, with two dogs now remaining symptom-free over a year following surgery. Dr. Bruyette anticipates an intra-operative mortality rate of 2 to 5 percent, and an 85 percent success rate with full remission of symptoms, based on results seen in the Netherlands, where this type of surgery has been performed for several years.

Most dogs remain hospitalized for five to seven days following surgery. Because the pituitary gland controls the sleep/wake cycle, some dogs remain “sleepy” for longer than that. Dogs who live in the area can return home even if still sleepy, but those from outside the area might have to remain hospitalized for up to an additional week. The clinic can work with clients from out of the area, even helping to fly their pets back when ready. Cost of treatment is currently estimated to be $8,000 to $10,000, which should decrease over time.

Currently, Dr. Owen has performed surgery only on dogs with “macrotumors” – those larger than 1 cm. Most pituitary tumors (90 percent) are “microtumors,” too small to be seen by the naked eye. Eventually, they hope to treat tumors of any size. When the tumor can be visualized well, it is sometimes possible to remove the tumor and leave the pituitary gland.

If the tumor cannot be visualized, or cannot be separated from the pituitary gland, the whole gland is removed (“transsphenoidal hypophysectomy”). Veterinary surgeons in the Netherlands have focused on this type of surgery. When the pituitary gland is removed, dogs must be supplemented with thyroid hormone and prednisone to provide cortisol that the body can no longer produce on its own.

Dr. Owen has trained veterinary surgeons at the VCA facility in Boston. She and Dr. Bruyette plan to offer a course on the East Coast later this year to teach other veterinarians to do the procedure. Dr. Bruyette estimates that eventually 5 to 10 specialty facilities in the U.S. will offer this treatment.

Dr. Bruyette also says, however, that ultimately another solution may become available. The doctors hope to do clinical trials on a substance that shrinks pituitary tumors in the laboratory. This oral medication is currently being tested on two dogs, but it’s too soon to know how well it’s working. The researchers are looking for other dogs to participate in clinical trials. Dogs must have a large tumor verified by MRI. Subsequent MRIs will be done at two and three months after starting treatment. If interested, email David.Bruyette@vcahospitals.com.

– Mary Straus

Orthopedic Equipment for Dogs Designed for Increased Mobility and Extra Support

Do you have a dog recovering from orthopedic or neurologic surgery, one who has mobility issues, or a senior dog who has arthritis? If so, at some point, you have probably wished you could do something – anything! – to help make your dog’s life (and your own) a little easier.

As someone who has shared her life recently with two large breed, geriatric dogs, I can attest firsthand that having a little bit of help can make all the difference in the world. Axel, our 85 lb. Bouvier, in particular, needed assistance toward the end of his life with getting up from lying down, being lightly supported during toileting, and occasionally steadied while walking. We used a few of the products listed below and found that they helped him maintain a good quality of life, mobility, and independence while lessening the physical strain on us.

I asked two veterinarians who specialize in canine rehabilitation to share some of their top picks for canine assistive/rehabilitative equipment. Laurie McCauley, DVM, CCRT, is founder and medical director of TOPS Veterinary Rehabilitation in Grayslake, Illinois, and is considered one of the pioneers in the field of veterinary rehabilitation. Evelyn Orenbuch, DVM, CAVCA, CCRT, recently opened Georgia Veterinary Rehabilitation, Fitness and Pain Management in Marietta, Georgia, and has focused on veterinary rehab medicine since 2003. (Full disclosure: I have worked with Dr. Orenbuch in my capacity as a marketing consultant during the launch of her new clinic.)

Photo courtesy Blue Dog Designs

Orthopedic Dog Harnesses

My favorite tool (and that of both veterinarians) is RuffWear’s Web Master™ Harness, described as a supportive, multi-use harness. Originally designed for dogs with active lifestyles (e.g., hiking, search and rescue), the harness has gained a big following with pet people looking for a way to give their dogs assistance in getting up and moving around, whether it be post-surgery or due to a degenerative or other medical condition. The harness features a well-placed, large handle, and is sturdy, machine-washable, and great for helping a dog up, or providing a steadying hand. The only downside is that the dog is required to lift a front paw to get into the harness. Suggested retail price: $50.

Offering more support is the Help ‘Em Up Harness from Blue Dog Designs. Both vets and I also give this product four paws up. The Help ‘Em Up is a complete shoulder and hip harness system, featuring two comfortable, rubber handles, one at the front and one at the back. The harness is well made, machine washable, and the front support is detachable from the back. To put the harness on, you don’t need to lift any of the dog’s limbs; I was even able to put it on my Bouvier, Axel, when he was lying down. Suggested retail price: $90 to $110.

Both the Web Master and Help ‘Em Up are comfortable enough for the dog to wear throughout the day in the house.

Orthopedic Foot Wear for Dogs

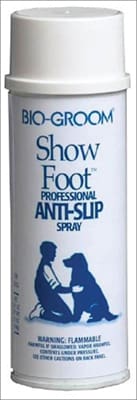

For dogs who have difficulty navigating slippery floors, Dr. McCauley likes Show Foot™ Anti-Slip Spray by Bio-Groom. Show Foot can be sprayed directly on the bottom of the dog’s feet (pads), or, if the dog is sensitive to the spray sound, can be sprayed on a cotton ball and dabbed on. The spray makes the feet feel tacky so they are less likely to slide on indoor slick surfaces.

Having hardwood floors in our house, I tried this product with Axel and found some success. It did leave some smudges where he walked, but they were easily wiped up. Priced at about $10.

Particularly for outdoor use, but great for any dog needing extra traction indoors or out, Dr. McCauley recommends Thera-Paw boots by Thera-Paw. These boots are made of a comfortable, breathable, lightweight, washable neoprene material. They are unique in that they have a front opening, so they’re great for dogs who don’t like to put their feet into boots. The boots use a Velcro closure, and have a natural flex point.

Although suitable for indoor use, these boots are especially good for dogs who need help outside or who chew their feet. The boots are sold individually, which is a nice option if your dog needs only two. Suggested retail: $22.

Photo courtesy of Handicapped Pets

Mobility Devices for Dogs

For dogs who have limited hind end mobility and strength, Walkin’ Wheels offers a two-wheeled adjustable wheelchair that can be adapted as your dog’s needs change.

When a dog first requires a cart, he might be strong in the front end. But with time, or if he has a condition such as degenerative myelopathy, his front end can become weak, too. Dr. McCauley likes Walkin’ Wheels because the angle of the wheels, and therefore the cart’s balance point, can be changed to take the weight off of the dog’s front end, allowing longer ambulatory quality of life for him.

The company sells direct to consumers, and there are numerous instructional videos on fit and sizing on the company website. However, Dr. McCauley recommends that consumers work with their rehab veterinarian to get the correct fit. Walkin’ Wheels are priced from about $250 to $500.

For dogs who cannot put their full weight on their front limbs, but still have motor ability in their hind limbs, Dr. Orenbuch likes a four-wheeled cart, so that the dog can continue to engage his hind legs. A “quad cart” can give the dog support by transferring his weight to the wheels while allowing him to use his legs as much or as little as possible.

Photo courtesy Canine Icer

Putting a disabled dog into a cart does not have to signal the end, says Dr. Orenbuch. Depending on your pet’s condition, using a quad cart can actually speed the rehab process, allowing the dog to achieve greater mobility. She does not have a particular model that is a favorite. Talk with your dog’s rehab vet about whether your dog is a candidate for a quad cart.

Other Aids for Old or Injured Dogs

Dr. Orenbuch casts a vote for another Thera-Paw product, the Hind Limb Dorsi-Flex Assist. These light-weight custom braces provide support and stability for weak or dragging rear paws. Dr. Orenbuch likes them for dogs who have neurologic deficits such as degenerative myelopathy or disc disease, and whose rear toes knuckle, or turn under, as a result.

This product allows those dogs to walk nearly normally and have been used on dogs ranging from a 2-lb. Chihuahua to a 220-lb. Bull Mastiff. She cautions that they are not, carte blanche, for any dog with these conditions, and should be prescribed and fitted by your rehab veterinarian. They generally retail for $75 and up; this is typically a custom-ordered and custom-made product.

Photo courtesy Thera-Paw

Many older dogs have chronically overused or injured their wrists, resulting in arthritis. For those dogs, or others who have wrist pain or have stretched the ligaments that stabilize the wrist, Dr. McCauley recommends Canine Icer Carpal Wraps. Many people don’t realize that sore wrists are a problem for their dogs. How can you tell? If your dog has his shoulder and elbow bent, when you bend his wrist downward, his toes should be able to touch his forearm. If this motion is uncomfortable, or if he tightens his muscles or pulls away, then Carpal Wraps can help.

Carpal support is also good for dogs whose wrist joints bend the “wrong way” when they’re standing. These dogs have hyperextension, and carpal support can help slow the progression of arthritis and the accompanying discomfort. Dr. McCauley likes the Carpal Wraps because they do not stop the dog from using the wrist (immobilization makes the joint weaker) but work by preventing the wrist from hyper-extending (which is what causes pain). She recommends dogs wear them on walks or when playing or running around. Suggested retail price: $21 (each).

Lisa Rodier is a frequent contributor to WDJ. She recently assisted in the launch of the Georgia Veterinary Rehabilitation, Fitness, and Pain Management facility. She shares her home with her husband and senior Bouvier, Jolie.

Selecting the Correct Leash Length for Your Various Leash Training Exercises

When you think “leash,” chances are you think of a four-to-six-foot strap made of nylon, cotton, hemp, leather, or (horrors!) chain, with a snap that attaches to your dog’s collar at one end and a handle for you to hold at the other. You use it to keep him close to you when you take him for walks or other places where he has to be under control. But a leash can be so much more than that!

288

Let’s think outside the box. There’s no law that says leashes have to be a certain length, made of a particular material, or be limited to one snap and one handle. There are all kinds of things you can do with non-traditional leashes. Heck, there’s even a good use for the grocery store chain leash.

Long and Short Of It

It’s true that four to six feet is a good length for normal leash-walking. That’s long enough that you can leave slack in the leash, as is desirable when your dog is walking politely by your side, but short enough you don’t have a large wad of leash-spaghetti in your hands when you want to gather it up so no one steps on it. However, shorter can be good sometimes. So can longer. The following are descriptions of some other useful leash lengths, and what they have to offer.

–Tab: A tab is a three-to-six inch bit of leash that makes it easier to snag your dog in a hurry, if necessary, without grabbing for his collar – a move that many dogs consider rude or intimidating, and that sometimes can elicit aggression. You can leave a tab on your dog at home to corral him easily if the doorbell rings, or make it easier on all parties if he gets tense when you reach for him for any husbandry or management purposes. Sure, you’d like to desensitize him to collar grabs (see “Stay in Touch,” February 2011), but in the meantime a tab can keep you both happy.

A tab can also be useful at an off-leash training class, or at the dog park – again, if you want to quickly get him under control with minimum tension. Agility people use them a lot.

You can buy tabs commercially; I like the ones from sitstay.com (800-748-7829). Or simply cut an old leash to the desired three to six inches. You can also make one from scratch. The more tense your dog is about having his collar grasped, the longer you might want to make your tab.

Note: The tab should be removed from your dog’s collar for safety reasons when he’s not under your direct supervision.

–Drag line: A drag line serves a similar purpose as the tab, only more so. This is a four-to-six-foot (or longer) light line that stays attached to your dog’s collar when he’s in the house. You can step on it to prevent your dog from dashing out the door, jumping up to greet a guest, “surfing” the counter, or leaping onto an off-limits piece of furniture. Or, step on it to interrupt a game of keep-away when he has something he shouldn’t (after which you cheerfully trade him something wonderful for the forbidden object, of course.) You can probably think of additional uses for your own canine challenges – perhaps gently inviting your uncooperative pal out from under the bed. Drag lines are available commercially in strong, light materials such as parachute cord (petexpertise.com; 888-473-8397) or you can make your own. Remember to remove the line from your dog’s collar when no one is home to supervise!

288

–Long line or light line: These can run anywhere from 15 to 50 feet, and are for outdoor use. They are most frequently used for teaching reliable recalls at increasing distances (see “A Line on Insurance” on the next page). But they can also be used as an outdoor dragline for backup insurance when you’re not quite sure about your dog’s recall, and to give your dog more hiking freedom when you know you can’t yet trust his recall.

The long line is generally heavier – flat nylon or cotton canvas or marine rope – while the light line is usually parachute cord or some other strong nylon. (I like the ones from genuinedoggear.com; 813-920-5241.)

It takes some skill to manage long and light lines without turning them into a knotted mess, but it’s worth the effort. Although popular because they offer the easy convenience of self-rewinding, retractable leads have far too many drawbacks to be considered a viable training tool.

Caution: If you’re using your long line or light line as a drag line and your dog runs off, he can get tangled around trees and brush and need rescuing because he won’t be able to return to you. Be careful!

Design Makes a Difference

Is there a better mousetrap in the world of leashes? It all depends on what your needs are. A standard leash is certainly the workhorse of the leash-walking set, but there are others that just might be perfect for you and your dog. We’re not talking about the endless variety of designer colors and patterns to match every outfit and holiday; we’re talking function here.

There are couplers that let you walk two dogs without tangling leashes. Leashes that attach your dog to your bicycle. Leashes with two handles, one near the collar, that give you instant control if you suddenly need it (like the ones from fetchdog.com; 800-595-0595). There are hands-free/multi-function leashes that can change length or double as a coupler or a tether (thedogoutdoors.com; 513-703-0210), and non-slip grip leashes that give you added traction, even in the rain. (Check out the ones from ruffgrip.com; 800-547-3966. I’ve had one of these for a long time and love it!)

Agility folks even use special leashes that have been designed to contain their dog’s special reinforcers: tug toys! Clean Run (cleanrun.com; 800-311-6503) has a whole line of leashes that are designed for tugging.

Don’t forget the T-Touch Balance leash, with a snap at each end and a handle in the middle on a sliding ring so you can attach it to a collar and a harness (available from ttouch.com; 866-488-6824). You use the two ends of the leash almost like reins on a horse, to send subtle, gentle communications to your dog. A similar leash sold by Wiggles, Wags & Whiskers with their Freedom No-Pull Harness functions the same way (wiggleswagswhiskers.com, 866-944-9247).

288

Speaking of no-pull and thinking outside the box, here’s a handy tip: You can take that basic six-foot leash (any material other than chain), attach it to your dog’s collar, run it from the back of his neck, down behind the elbow, under his rib cage and up the other side, slip it under the leash where the clip is, around the front of his chest and bring it up under the leash on the other side, and you have an instant emergency no-pull harness.

Material World

Nylon, cotton, hemp, and leather are the materials most commonly used for training leashes. Some trainers prefer leather because it is less abrasive to your hands if your dog pulls. Nylon leashes tend to be the least expensive, with cotton and hemp close behind.

Long lines and light lines tend to be made of parachute cord and other light-but-strong nylon fibers. You can find cotton long lines, but some people complain about how heavy cotton gets when it gets wet (as when it gets dragged through wet grass).

Chain leashes have the most potential to cause significant injury to your hands. However they do have a narrow niche in a training toolbox: they can be useful for dogs who chew on (or chew through) their leather or fabric leashes.

Chain leashes can also be used to discourage a dog who tries to tug on his leash when you prefer that he not. With a non-chain leash, when you resist your dog’s pulling (you can’t just drop the leash and let him go!) he gets reinforced for his inappropriate leash behavior (it’s fun!) – so his leash tugging and chewing may persist and even increase. Most dogs find biting on metal chain mildly aversive, so they learn to keep their teeth off their leash while you work to reinforce more appropriate behaviors.

The other critically important piece of your leash or long line is the snap. You want a leash with quality hardware that won’t rust, corrode, freeze up, or otherwise fail you in an emergency. The last thing you need is a snap that pops open or breaks at the exact instant your dog reaches the end of it. Extra soft, strong, nylon webbing leashes and long lines fitted with very sturdy brass hardware are available from White Pine Outfitters (whitepineoutfitters.com; 715-372-5627).

It’s well worth spending more for well-designed, good quality leash equipment that can last the life of your dog, and might save your dog’s life one day. One of my favorites is the well-made 30-foot light line at Genuine Dog Gear. At $22.95, that’s less than $1.50 per year for a dog who lives to be 15, or four tenths of a cent per day. Another is the 50-foot soft web long line from White Pine Outfitters. At $55.60 that’s still only $3.70 per year, or a penny a day. Isn’t he worth at least that?

On-Leash Training Blossoming into Off-Leash Reliability

The transition from on-leash training to off-leash reliability can be a frustrating challenge. “But he knows what ‘come’ means!” a client wails, and points as proof to the fact her dog comes impeccably, every time, when called in the training center, the house, or the backyard.

Her dog does know what come means – in the training center, in the house, and in the backyard. He also knows that when he’s hiking in the woods, chasing squirrels and rabbits is far more rewarding than coming back when he is called, especially since “Come” often means “The hike is over, the leash is going on the collar, and we’re returning to the car.”

A long line is a valuable tool that can help you navigate the transition from “Coming reliably when called within a safe, controlled area” to that pinnacle of dog training: “Coming reliably when called regardless of where we are or what other exciting things are happening.”

The purpose of the long line is simply to restrain your dog so he can’t be reinforced by tearing after Bambi in the woods. It’s up to you to make yourself interesting and exciting enough to get him to return to you. The long line is not for yanking or dragging him back to you; that will only serve to confirm his opinion that playing in the woods is more fun than hanging out with you!

Here’s the right way to use a long line as a training tool:

–Train a wildly enthusiastic “come” response in controlled environments. Practice with a long line in controlled circumstances as well as doing off-leash recalls, so the long line becomes part of the recall fun.

–Use enclosed areas of different sizes to practice with your dog on and off of the long line. Find a friend with a securely fenced pasture of an acre or more or go to a fenced community dog park during low-usage times when your dog won’t be distracted by other dogs, so you can do your off-line work without worrying that he will disappear into the National Forest for days at a time.

Note: If you plan to drop your long line and let the dog run with it attached to his collar, be sure you are not training anywhere where he might vanish into the woods and become inextricably tangled around trees and brush.

–Whenever you arrive at a new location, do five or ten minutes of enthusiastic recall practice on the long line, interspersed with other good manners training, before removing his leash. Then do a few minutes of focused off-leash training. This will teach him that training happens even in exciting places – a trip to his favorite park does not mean immediate and total lack of control, and removing the leash is not an invitation to charge off into the brush.

–When you first let your dog off the leash, do some short recalls and make them very rewarding and fun – deliver his absolute favorite treat that he only gets when he comes when called, or a quick game of tug with a toy or fetch with a ball that he obsesses over.

–As you hike the enclosed area with your dog, look for opportunities to call him when he’s very likely to come: when he’s looking a bit bored, not when he’s fixated on a squirrel up a tree or totally preoccupied digging a hole. When he comes, make wonderful things happen, then let him go play again. This teaches him that “come” means “wonderful yummy fun-stuff break and then go play,” not “fun’s over, time to go home!”

–Occasionally during the outing, put the long line back on his collar, hold it, and walk with him no more than 10 feet away from you on the line (this works in better in open pasture than in heavy woods and brush). When one of you spots a squirrel or a rabbit, call him to you. When he comes, tell him what a wonderful dog he is, have him sit, feed him a treat if he’s interested, then release the line, and say “Go chase!” Run toward the squirrel with him to encourage him, if he needs it.

If he doesn’t come, don’t get angry and don’t drag him back to you with the long line. Just wait, holding the line, until he realizes he can’t get to the squirrel and returns to you.

This is the “Premack Principle” which says that the way to get something really wonderful is to do something less wonderful first. In this case, the road to “squirrel” is through “come to me.” As he gets better and better at responding, let him range farther and farther, dragging the long line until, he will “Premack” back to you from 50 feet or more in order to earn his squirrel chase. (Premack also gives the squirrel a significant head start to the nearest tree.)

When your dog returns reliably from the distant reaches of the long line even in the face of thundering herds of squirrels and rabbits, start Premack off-leash. Do your first off-leash test when your dog is near you. When he sees a squirrel at a distance call him, reward with his favorite reinforcer, have him sit, and then tell him to “Go chase!”

If he takes off after the squirrel instead of coming, don’t keep calling. Wait until he tires of the squirrel, then call him back to you in a pleasant tone, and go back to practicing on the long line. Do not punish him!

The reliable recall, trained with the help of a long line, can serve you well in a variety of challenging circumstances. The temptation can be other dogs playing, an invitingly cool pond on a hot day, or a steaming-fresh pile of horse manure. You could be the dog owner who can proudly say, “My dog knows what ‘Come’ means – everywhere, every time!”

A new look at the Westminster Dog Show

If you, like me, grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area and have always been a dog lover, your parents probably took you to see the Golden Gate Kennel Club dog show several times. By the time I was an adult, I had been to this show six or seven times. It’s a big show, held in a big venue, and it draws huge crowds of dog-loving fans. Many people sit in the stadium seats and watch the show rings, but of course, since it’s a benched show, with the dogs required to be present and viewable in their assigned spots for the entire day, spectators also spend a lot of time walking the aisles of the benching areas, petting dogs, talking to their owners, and taking jillions of photos. It’s a dog lovers dream – but probably not nearly as enjoyable for the dogs, who have to endure countless intrusions into their personal space and all those jillions of photos.

What I learned the first (and only) time that I attended the Westminster Dog Show, held in recent decades at Madison Square Gardens in Manhattan, was that the Golden Gate show was way more pleasant for the dogs than Westminster. On TV, Westminster always looks so glamorous and plush. My impression of the bench areas, however, was that of a nightmare for the dogs. Space is at a premium; the dogs are squished into tight spaces, and the aisles are PACKED with humans. Also, it seems as if every person is carrying more than one camera. I had a camera, too, but I couldn’t figure out how to get a picture of any single dog without 10 other people with cameras in the frame, so I gave up.

Worst of all, even though New York City was experiencing a typically cold winter when I was there, it was HOT in the benched areas, and fans were aimed at many dogs in an effort to keep them comfortable. It was noisy, hot, and smelly – and I gained a huge amount of respect for the dogs for not coming completely unglued in that environment, and for the handlers who could somehow support and maintain the dog’s enthusiasm for the show ring after enduring hours and hours of grooming and crowds “backstage.”

I’m much more enthused with the latest way to enjoy the Westminster show (which is concluding today, on February 15) – through its Facebook page! The organizers are posting hundreds of bits of news, gossip, and trivia each day, and fans of the dogs and the breeds are commenting on each and every post. Reading through the posts is bringing the show alive again for me. I love learning about the stories behind the dogs – who they are, who the owners, breeders, trainers, and handlers are, and what sort of adventures they’ve had on their way to their moment in the spotlight. Reading the stories, I feel like a dog-loving kid again. Check it out, and tell us what you think: http://www.facebook.com/WKCDogShow