[Updated December 18, 2018]

TOOTH FRACTURES IN DOGS: OVERVIEW

1. Arrange for a comprehensive oral health assessment for your dog performed by a canine dental specialist.

2. Provide toys that will not break or abrade your dog’s teeth when chewed or mouthed.

3. Practice good dental care at home by brushing your dog’s teeth daily with a toothpaste made for dogs.

4. Leave tooth scaling to the professionals.

Between runs at a recent agility competition, I was chatting with Katie and Nora, a couple of handlers I often see at trials. Coincidentally, all three of our dogs had received an annual health examination from our respective general practice veterinarians recently, with all dogs earning good reports. And all three of us had been told by our veterinarians that our dogs had broken or chipped teeth. My veterinarian had noted a “slab fracture of the upper fourth premolar” on the health summary report for my 10-year-old Border Terrier, Dash. The recommendation we were all given: “Keep an eye on the teeth.”

Katie said she had observed a red “pimple” or swollen spot on her dog’s gum right over her dog’s broken tooth just that morning. She had decided that the waiting and watching were over and she was going to bring her dog to a canine dentist.

Within a couple of weeks we found ourselves together again and Katie told us the outcome of her dog’s visit to the canine dental specialist. The dentist discovered an old fracture in one tooth that had broken through the enamel, dentin, and pulp layers of the tooth. The pulp area of the tooth was exposed and dead. The root had abscessed and the infection had broken through into the gum, creating the red “fistula” or pimple Katie had noticed.

The dentist discovered a second broken tooth that had gone unnoticed, but which also had abscessed and sustained significant damage to its crown. The dentist performed a root canal on the first tooth, and surgically extracted the tooth with the crown too damaged to save, thereby eliminating sources of infection and chronic pain in her dog’s mouth.

“The dentist told me I had waited much too long to repair the teeth and that these conditions caused a lot of pain for my dog, not only when the initial damage occurred, but on an ongoing basis. They also created a chronic infection in my dog’s mouth that could impact her overall health,” Katie told Nora and me.

Within 24 hours, Nora and I both made appointments with canine dental specialists to have our own dogs’ oral health fully evaluated. All three of us have learned that our dogs’ teeth should receive frequent and professional attention, and that earlier interventions could prevent a lot of pain for our dogs – and our pocketbooks!

A Thorough Canine Dental Exam

I scheduled a comprehensive dental assessment for Dash with Timothy Banker, DVM, FAVD (Fellow, Academy of Veterinary Dentistry) in Greensboro, North Carolina. A practitioner of advanced canine dentistry for more than 26 years, Dr. Banker started by giving me a “tour” of the anatomy of a dog’s tooth and the structures that support it in the jaw.

The tooth consists of the enamel, or the hard but thin outer layer. Beneath the enamel is the dentin, a porous material that looks like a sponge under a microscope. Soft pulp fills the inner cavity of each tooth, sometimes called the pulpal chamber or root canal. Each pore in the dentin contains nerve fibers that connect with the pulp, making the interior of the tooth very sensitive.

The structure that supports each tooth is called the periodontium. It consists of the cementum, which lines the root of the tooth below the gum line; the periodontal ligament, which attaches the tooth to the alveolar bone; and the gingival tissue, or gum, which surrounds the tooth roots.

“It’s important to evaluate both the teeth and the periodontium in a comprehensive oral examination,” says Dr. Banker. Dr. Banker described the steps he and a technician specifically trained in canine oral procedures would take during Dash’s dental assessment:

With a dog under anesthesia, Dr. Banker first looks at the inside of the dog’s mouth, at the outside and inside surface of each tooth, and compares one side of the dog’s mouth with the other for inconsistencies or asymmetry. He checks for retained puppy teeth, crowded teeth (teeth too big for the size of the dog’s mouth), signs of oral cancer, and any indications of trauma to the mouth. He checks for malocclusions, or bad bite patterns, since poor tooth alignment can cause trauma when teeth don’t meet properly or injure the soft tissue in the mouth.

Next, he palpates, or feels, inside the dog’s mouth for problems not visually appreciated. Using a probe, he examines the periodontium surrounding each tooth, detecting and measuring any pockets that can host bacteria. Pockets result from the loss of tissue and bone when a dog’s body reacts to the bacteria contained in the plaque in a dog’s mouth. After identifying any broken teeth, he uses a probe to measure the depth of the break or fracture, determining how far into the tooth the injury extends. He takes color photos to document his findings.

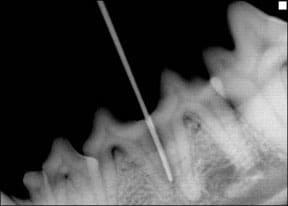

Next, Dr. Banker takes digital radiographs to evaluate the status of the dog’s mouth below the gum line, including damage that has occurred without exterior evidence, the presence of suspected abscesses at the root of injured teeth, loss of bone or ligament strength due to injury or infection, and to confirm the depth of any periodontal pockets. Finally, he thoroughly scales, cleans, and polishes the dog’s teeth.

“Cleaning is only a small part of a comprehensive oral assessment,” says Dr. Banker. “In an ‘awake’ oral exam, the doctor can screen only visually. Under anesthesia and using dental tools and radiography, the doctor can thoroughly examine each of the dog’s 42 teeth, including the fine details. Doing a full diagnostic evaluation – that’s where it all starts.”

My Dog Fractured Her Tooth

After Dash’s diagnostic procedure, Dr. Banker and I met to discuss his findings. Dash had a slab fracture (a section of the crown of her tooth had sheared off) of her upper left fourth premolar with direct pulpal exposure, deep periodontal pockets around the tooth, and indications of an abscess at the root. She had a fracture in her upper right fourth premolar that extended into the dentin and pulp, also with indications of root abscess.

Dash also had a deep periodontal pocket around another tooth, and bone loss at the root of her lower central incisors (two little front teeth on her bottom jaw). One of these little incisors was loose due to the loss of bone, although I had never noticed it. All of these conditions were possible sources of pain and infection. Only the slab fracture was visible by looking in her mouth.

“If a person got any of these injuries,” Dr. Banker commented, “he would be complaining and going to the dentist immediately.”

Considerations for When Deciding on A Dental Procedure for Your Dog

Dr. Banker and I discussed a treatment plan for Dash. He talked about some factors he considers when counseling clients about treatment options:

– Is the tooth strategic (needed for holding or chewing, like a canine tooth or a molar) or is it more cosmetic (an incisor that’s visible in the dog’s “smile”).

– How deep is the fracture?

– What is the condition of the root?

– What is the condition of the remaining crown of the tooth?

– What is the age of the tooth? Immature teeth with significant root damage are more difficult to save than mature teeth.

– What is the age of the dog? An extraction, which requires less time under anesthesia, may work better for an elderly dog with other health problems; saving a strategic tooth using a root canal procedure may work better for a young dog or a healthy older dog.

– What is the condition of the periodontium surrounding the tooth?

– What is the whole medical history of the dog?

– What is the anticipated subsequent behavior of the dog?

Dr. Banker talks with each owner about the behavior that likely caused the tooth damage and assesses what changes can be made after treatment.

For instance, if a client gave her dog hard toys and rawhide chews, and her dog broke his tooth on one of them, Dr. Banker asks if the dog will continue to have access to hard toys and rawhide chews after the procedure. If the answer is yes, Dr. Banker may advise the client to extract the broken tooth rather than save it with a root canal. After all, continuing to chew hard objects is likely to reinjure the tooth and require extraction in the future.

After a canine dentist has performed a root canal on a tooth, the structure of the tooth has been compromised although it has been returned to good health. The tooth will not be as strong as a healthy, normal tooth and therefore becomes more susceptible to breaks in the future.

“I make every attempt to save strategic teeth,” explains Dr. Banker. “Extractions come with risks. Dog’s teeth are designed to stay firmly in the dog’s mouth. Many are large and firmly embedded in the bone and it takes effort to remove them.

“In a person, the crown-to-root ratio of a tooth is about 1 to 1 – that is, about half the tooth area is above the gum line and half resides below it. In a dog, the ratio is about 1 to 2 (twice as much tooth area resides below the gum line as above it). Serious complications can occur from extractions, like fracturing the mandible (lower jaw bone) or injuring the nasal cavity. If the extraction site is not closed properly, oral or nasal fistulas may result.”

In addition to extractions and root canals, a canine dentist may recommend root planing to clean out periodontal pockets, the removal of infected material from the gum tissue, grafting with implant material to fill and close pockets, and the application of time-release antibiotic and anti-inflammatory medications or tooth surface sealants.

In Dash’s case (she is almost 10 years old), we opted for a root canal of her right upper fourth premolar to save this strategic tooth. Due to the severe damage to the crown of her left upper fourth premolar with periodontal bone loss, Dr. Banker declared it a poor candidate for a root canal and advised surgical extraction of this tooth as well as her loose lower incisor. Due to the complex construction of the premolar, Dr. Banker relied on digital dental radiography during the procedure to insure that he had removed all of the pieces of the extracted left premolar and that the material he injected into the root canal of the right premolar had completely filled and sealed it. He applied implant material to her deep periodontal pocket to encourage healing and bone regrowth.

After about two weeks, during which Dash’s abscesses and surgical sites healed completely, she began to act like someone had subtracted five years from her life. She has more energy and stamina now, and flies around the agility course like a youngster again. That result is common, according to Dr. Banker.

“Dogs instinctively mask evidence of pain,” he says. “Isn’t it better to find early indications of potential abscesses by radiographs than to wait for painful infections to grow and break through the gum?” Long-term, painful and infectious conditions can drain a dog of vigor and strength.

Reputable Canine Dental Professionals

I asked Dr. Banker how owners can decide who should perform dental procedures on their dog. He suggested asking the veterinary candidates the following questions before making a decision:

– How much training do you have in this particular procedure? How long have you been performing it? More experience and training is better.

– How many of these procedures have you done on this particular tooth (canine vs. molar vs. incisor)? Molars and canine teeth are more complex in structure than incisors.

– Can you discuss how you would handle any complications that might result from this procedure?

– What kind of equipment do you use for root canals? Mechanized drills that shape the root canal predictably, Dr. Banker says, are superior to hand drills and files.

I asked Dr. Banker how much training in canine dentistry was typically offered in veterinary school. He answered, “It varies greatly from school to school. A few schools have canine dental departments and include dentistry in the core curriculum. Others offer dentistry as an elective and students can graduate without having received any training in dentistry at all.”

Dr. Alexander Reiter, D-AVDC (Diplomate of the American Veterinary Dental College), D-EVDC (Diplomate of the European Veterinary Dental College), is an assistant professor of dentistry and director of the Dental Residency Program at the University of Pennsylvania School of Veterinary Medicine in Philadelphia. UPenn provides an extensive core curriculum in veterinary dentistry.

“Canine endodontics can’t be taught in a weekend of continuing education,” states Dr. Reiter. “It requires years of experience to consistently show good outcomes. Accessing, filing, shaping, cleaning, sterilizing, drying, filling and restoring a root canal takes skill and practice.

“A dog should have an annual oral examination performed by a canine dental specialist,” he continues. “A dog may present with jaw swelling, foul breath, inflammation of the soft tissue in the mouth, altered eating habits, lack of energy, and other dramatic indications before a veterinarian or owner may become aware of a problem.

“I consider [conditions like tooth fractures, abscesses, and periodontal pockets] to be open wounds in a dog’s mouth and the daily source of inflammatory material deposited directly into a dog’s bloodstream. These conditions need immediate attention.”

How to Prevent Tooth Damage

The doctors described how dogs usually injure their teeth and gums, and how owners can prevent it.

“My son was playing hard tug with his Golden Retriever-mix when the dog yelped and dropped the tug toy. I checked his mouth and one of his teeth had turned pink. The dog had injured the pulp in his tooth and it was hemorrhaging internally, even though the tooth had not suffered a break or fracture. Internal tooth damage can result from a concussion as well as from a break,” Dr. Banker said.

Dogs have 10 to 20 times the bite strength of a person. When they bring that to bear on a hard object, like a cow hoof, something’s gotta give, and it’s usually the dog’s tooth. “It’s a myth that dogs need to chew on hard things,” comments Dr. Banker.

According to Dr. Reiter, plaque mineralizes on teeth in two to three days and then cannot be removed by simple brushing. Teeth that are not brushed build up a layer of bacteria-laden plaque that can cause periodontal disease and, upon entering the bloodstream, can cause diseases of the kidney, liver, lungs, and heart valve. “I estimate that 80 percent of dogs have constantly inflamed gums,” he says.

Tennis balls, especially wet and dirty ones, are abrasive and can wear the protective enamel off dogs’ teeth. Some dogs like to chew on large sticks, stones, rocks, and even large ice cubes.

“Regarding prevention,” Dr. Banker quips, “as a colleague of mine says, ‘If you wouldn’t hit yourself in the kneecap with it, don’t give it to your dog to chew!’ Provide toys with smooth surfaces for your dog and avoid tennis balls.”

Oral Hygiene for Your Dog at Home

Both Dr. Banker and Dr. Reiter agree that regular tooth brushing with a toothpaste made for dogs is the single most important step an owner can take to prevent canine oral health problems. They recommend brushing twice a day if possible, or at least once a day. “Daily brushing encourages owners to look in their dog’s mouth regularly and notice changes and problems,” adds Dr. Banker.

Dr. Reiter emphasizes the importance of a high quality diet. He suggested that owners discuss the usefulness of products such as dental rinses, gels, and sealants with their canine dentist. Of course, a regular oral health evaluation by a knowledgeable canine dental specialist ranks high on his list of preventative measures.

Both doctors discourage owners from hand-scaling plaque from their dog’s teeth at home. Dr. Reiter explains that scaling at home can place tiny scratches on the surface of the tooth, thereby making it more prone to retain plaque build-up in the future. Canine dental specialists polish a dog’s teeth after scaling to restore a smooth tooth surface.

Also, during scaling at home, a dog may jerk away or turn his head unexpectedly, causing the scaling instrument to lacerate the dog’s gum. An owner could dislodge a chunk of plaque that the dog could aspirate into his lungs. An owner who is unskilled in scaling a dog’s teeth could cause the dog to become nervous about people looking and working in his mouth.

“Home scaling does not reach sub-gingival (below the gum line) material or into any pockets around the dog’s teeth,” says Dr. Reiter. “And don’t be tempted to bring your dog to a groomer or other person who advertises anesthesia-free dental cleanings. There’s a lot of water spraying around during a dental cleaning. Canine dental professionals use a cuffed endotracheal tube to administer anesthesia during the procedure. The tube has an inflatable collar that protects against the accidental aspiration of water and debris into the dog’s lungs. Only an ‘asleep’ procedure insures sufficient cleaning of the teeth above and below the gum line in an environment that’s safe for the dog.”

“Supra-gingival (above the gum line) scaling is mostly cosmetic, not therapeutic,” agrees Dr. Banker. It creates an inappropriate, false sense of security that ‘the problem has now been handled.’ The removal of sub-gingival plaque and calculus is the most important part of the treatment of periodontal disease.”

Of Teeth and Bones

by Nancy Kerns

Many of WDJ’s readers feed their dogs a home-prepared diet that includes a certain amount of raw bone (such as chicken necks or wings); many others offer their dogs large, raw meaty bones for recreational chewing. Most veterinary dentists frown on these practices, due to the potential for injury to the dogs’ teeth. Damage from chewing bones can and does occur to some dogs who chew or eat bones; however, many raw feeders are aware of the potential for these injuries and feel that the benefit of the diet far outweigh the dental risks. Other owners prefer not to take these risks, including raw bone in their dogs’ diets only in a freshly ground form.

If you are one of the owners who do feed bones to your dog, you can make the practice safer for your dogs’ teeth by taking the following precautions:

A) It’s crucial to be familiar with your dog’s chewing style before you give him any sort of bones. Does he try to get chew objects between his back teeth and bear down with all his might? Does he tend to wolf down whatever he’s chewing? Has he ever broken a tooth while chewing? If so, in our opinion, you should give him only Kongs or other safe, indestructible chew toys for recreational chewing. Letting him loose on any type of recreational bone could invite serious trouble.

Only moderate and light chewers should be given recreational chew bones. And in either case, supervision is essential.

B) Start giving your puppy fresh recreationial chew bones when he is very small. Dogs who grow up chewing on bones tend to handle them more casually and adeptly than dogs who get them only as a rare treat. lnfrequent, overenthusiastic chewing is bound to cause a problem.

C) If at all possible, buy a fresh, raw bone from your butcher. Some supermarkets can provide frozen raw bones. Ideally, buy fresh bones that have lots of tissue still clinging to them. Tearing the tissue off the bones provides great exercise and entertainment for your dog.

D) Buy bones that are too large for your dog to fit between his back teeth.

E) Discard any bone after a day or so of chewing. As bones dry out, they become harder and more brittle, increasing the danger of splintering. The bacterial count on an old bone will also increase as time passes.

F) Choose joints, like knuckle bones, instead of straight, tubular marrow bones, which are harder and stronger (because they are weight-bearing bones) and can damage your dog’s teeth with less chewing pressure.

G) Avoid narrow bones like ribs, which even small dogs can get between their back teeth, or any bone that has small pieces that could break off and cause a choking or blockage hazard (such as a shank fillet).

H) Don’t buy “sterilized” or dry bones, which can be extremely brittle.

Dental Health is More Important for Dogs Than You Think

“Years ago,” Dr. Banker recalls, “I had a friend and client who brought his six-year-old Golden Retriever to me for the dog’s first oral health exam. The dog’s two lower canine teeth were fractured, exposing the pulp, which was now dead. I suggested doing a root canal on the teeth. My friend just laughed. However, after some thought, he did take my advice and I performed the work. Two weeks later he called and asked me ‘Banker, what have you done to my dog? He’s acting like a puppy again!’ ” Today, root canals for dogs are becoming well-accepted by owners and are no longer a laughing matter.

Dr. Banker will check Dash’s root canal in six months. Following her experience, I brought my six-year-old Border Terrier, Chase, to Dr. Banker to have his own dental assessment and cleaning. Fortunately, Chase had no fractures and only one small periodontal pocket to treat. As with most terriers, his teeth are crowded; we will watch for any periodontal disease that may develop due to the twisting of his large teeth in his small mouth.

Now, like me, my dogs have a dental specialist to help optimize their health.

Lorie Long, an agility enthusiast, lives in Virginia with her husband and two Border Terriers. She is the author of The Siberian Husky (TFH, 2007) and A Dog Who’s Always Welcome: Assistance and Therapy Dog Trainers Teach You How to Socialize and Train Your Companion Dog (Howell, 2008).