[Updated January 10, 2019]

INSTINCTUAL DOG BEHAVIOR OVERVIEW

- If your dog is a purebred, or is a mixed breed dog that greatly resembles a specific breed, look into the historic origins of the breed to determine what sort of work the dog was developed to perform.

- Give your dog the opportunity to use his inherited gifts during recreation or work. For example, allow dogs that are known for scent work to smell, and dogs who were bred to herd or work to run (a lot!), whether at the dog park or on a jogging path.

- Look for opportunities to train your dog for activities that harness the skills and predispositions of his breed or type.

No one knows whether dogs chose humans or humans chose them, but whatever the case, we’ve been partnered for a long time. We welcomed canis lupus familiaris into our fold – and then much later began carefully and strategically breeding them to produce dogs who would readily perform various specialized tasks. They helped humans hunt, gather, and retrieve game, rid us of vermin, herded and guarded our flocks, and protected us from dangerous interlopers. Even the smallest toy breeds were ratters by day, and lap warmers by night.

Our liaison was one of mutual convenience. We provided food, warmth, and shelter, and in turn, they performed services we needed – but their work didn’t preclude them from acting on their instincts and expressing behaviors that came naturally to them. It was a great working partnership that still exists in some parts of the world.

In this country, though, few pet dogs have any sort of job to do. Seem like a nice gig? Free food and lodging, with almost no expectations? Well . . . except for the fact that they have to give up the right to act on their instincts and may no longer express many behaviors that come naturally to them. For a dog, it’s maybe not such a good deal after all.

As a dog trainer and behavior consultant, I feel that it’s no wonder that many of the “problem dogs” I’m paid to work with are expressing undesirable behaviors; they’d likely be perfectly fine if they were living in a different time and circumstance, able to perform the work and do the things they most enjoy doing. The simplest prescription? Adopting a program of training and activities that suit dogs of their background can greatly enhance the dogs’ lives and enable them to live more successfully in our world.

Why Do We Choose Certain Dog Breeds?

Many people choose their canine companions based on aesthetic reasons; they like dogs who are a certain size or color, or who have a certain type or length of coat. Some will admit they chose their dog because it looked “just like” one on TV or in the movies, or out of nostalgia for a childhood dog, conjuring fond memories of times gone by. They may have read or heard that dogs of a certain breed are “good with kids” or “hypoallergenic,” or make “great apartment dogs.” But how many people select their dogs based on what that type of dog was originally bred to do? Very few!

While the majority of dogs in the U.S. are mixed-breeds, the rest (an estimated 40 to 45 percent) are purebreds. Not all purebreeds are recognized by the American Kennel Club (AKC), but the AKC is the largest registry of purebred dogs in the U.S. It recognizes around 200 breeds, which it organizes into formal “groups,” based on the work that the dogs where originally bred to do. According to statistics based on AKC registrations, among the current top 20 most popular breeds, five are working breeds; three apiece are in the sporting group, herding group, toy group, and “non-sporting” group (this is merely a catch-all group for dogs that don’t specifically fit in any other category); two are in the hound group, and one is in the terrier group. It’s safe to say that the majority were bred with specific characteristics and behaviors that helped make them more efficient at their jobs.

Specific characteristics and a predisposition to certain behaviors are also inherited by mixed-breed dogs; the more genetic contribution a mixed-breed dog receives from a purebred gene pool, the more likely he is to act like his purebred ancestors.

Why does this matter? Knowing what drives and motivates a dog’s forebears can inform his owner as to what is most likely to motivate him, lead to greater harmony and training success for that dog.

This is not to say that every individual dog within a breed should be expected to behave the exact same way. However, there are some distinctive breed-typical characteristics that have been selected and concentrated throughout that breed’s history that could very likely affect behavior.

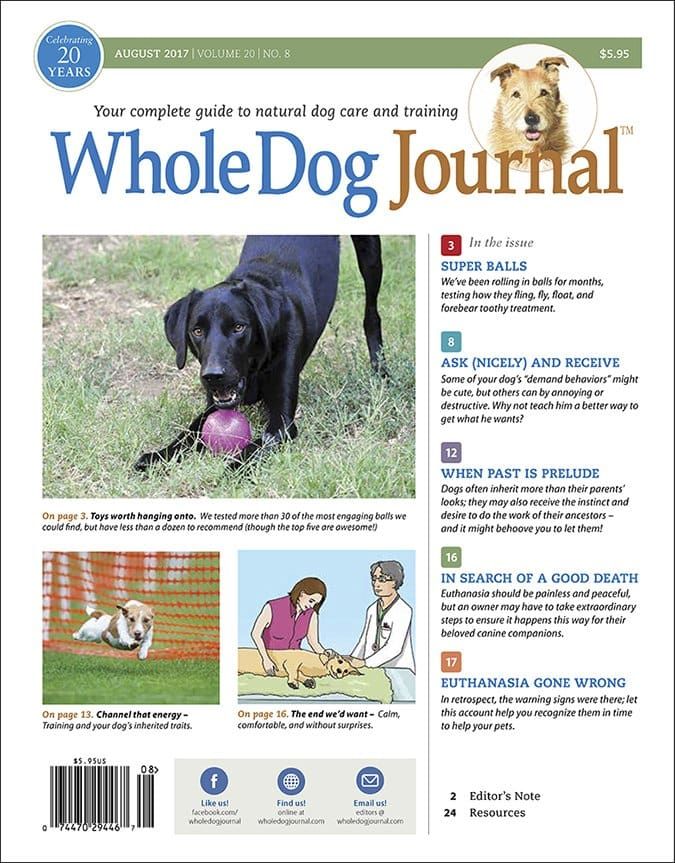

Sporting Dog Breeds

Sporting breeds – Pointers, Retrievers, Setters, and Spaniels – were bred to work alongside and help the hunter on land and in water, with a strong prey drive and the strength and stamina to hunt and swim all day if needed. Does this mean all Labradors will be natural swimmers? No. Or will all Pointers and Setters be “birdy”? Not necessarily. However, most that I have met through the years have been full of energy – and when that energy is not directed toward productive activities, it can manifest in a host of undesirable behaviors such as reactive behavior, destructiveness, excessive barking, and hyperactivity. The result can be the dog being deemed as stubborn and untrainable, which couldn’t be farther than the truth.

These breeds were specifically bred to follow cues and direction, making them extremely biddable – when their physical activity needs are met, which isn’t always easy. A walk around the block or a 20-minute game of fetch when you come home for work just might not be enough.

This doesn’t mean you must take up hunting! You can simulate that work by participating in field trials and hunt tests. These sports train your dog to use his instincts to point to, flush, and retrieve game. There are fewer things as exciting as watching a young dog’s instinct kick in! A baby Irish Setter who’s never seen quail before “pointing” at one hidden in the brush without ever being taught is a sight to behold.

Agility, bikejoring, fly ball, cani-cross, dock diving, and scootering are some of the other sports and activities that can provide both physical and mental exercise for active breeds. They also promote team work between dog and owner, and help the dog’s build confidence.

Barbara Long of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, has shared her life with Gordon Setters for quite a few years and currently has two. “If they get enough exercise, they can be quite calm in the house,” writes Barbara. “Mine have been biddable but outwardly directed, independent, and persistent, which is pretty characteristic of the breed.” Barbara regularly participates in rally, tracking, and canine freestyle with her dogs.

At this writing, there are more than 24,000 Labs and Goldens alone listed for adoption on petfinder.com, and thousands of other sporting breeds and predominant sporting breed-mixes. I wonder how many of those dogs could have had been more successful in their homes if they’d had access to these types of activities?

Working and Herding Breeds

Working breeds, such as Rottweilers, Doberman Pinschers, Boxers and Great Danes, were bred to be keepers of the castle and ward off trespassers, so it never surprises me when I receive a call from a worried owner of a 10-month-old Mastiff who seems wary of strangers. It starts to make even more sense when I learn the dog has never been to a group training class and rarely leaves the house or yard.

While all dogs need and benefit from early socialization, anyone choosing a working breed should expect to socialize, socialize, socialize; and when they think they’ve done enough, socialize some more! Dogs of working breeds should be introduced to new people and places regularly – while young, and through adolescence and adulthood. Group training classes are a great place to accomplish this. The dogs will have the opportunity to meet new people and dogs of all kinds in a controlled, predictable environment.

Sports and activities that involve thinking and problem solving, such as tracking, scent work, competitive obedience and rally obedience, are great to try with many of the working breeds. Of course, many of the working breeds are used in the specific activities for which they were developed, such as water rescue (Newfoundlands, Portuguese Water Dogs), drafting and carting (Saint Bernards, Bernese Mountain Dogs, Greater Swiss Mountain Dogs, Leonbergers), and sled pulling (Siberian Huskies, Alaskan Malamutes).

Jill Greff of Ottsville, Pennsylvania, has had Bernese Mountain Dogs since 2001. “I have done obedience, rally, agility, and herding with my Berners. Mostly I found they respond best to positive reinforcement and are both food- and praise-motivated,” says Greff. “Berners do things in their time. It may look like they are moving slow, but in their mind they are hurrying! Patience is key.”

Primarily bred to herd sheep and cattle on working farms, today most herding breeds in the U.S. rarely live that lifestyle. Instead they live in metro areas and suburbs, and occasionally in townhomes, condos, and apartments.

How does that work? Well, one thing is certain: if there is herding instinct there, they will still find a way to express it, often by herding the children, family cat, or worse, by chasing cars and any fast-moving object, which can be very problematic and dangerous. The challenge is finding activities that can help satisfy that urge safely and constructively.

Treibball is a great sport for herding breeds. Created in Germany a dozen or so years ago, this sport requires a dog to “herd,” or gather and drive large exercise balls into a soccer goal. It is a skill that does take quite a bit of precision training, but herding breeds tend to be very quick learners. Additionally, many herding breeds excel at dog agility and competitive obedience and rally as well.

Hounds, Terriers, Toy, and “Non-Sporting” Breeds

Both hounds and terriers were bred to work independently of man – meaning, rather than directly follow our cues and directions, they followed their own instinct and drive. Hounds use their noses to locate everything from fox, rabbits, raccoons, wild pigs, and bears (and then use their keen sight and speed in pursuit). Terriers go to ground, using their powerful claws and shoulder muscles to dig for vermin and rodents.

This is important to know when training one of these breeds, as it can save your hours of frustration when they don’t seem to be listening and become easily distracted! I’ve found it most successful to first use the highest-value rewards to motivate them to work with you, and then shape the desired behavior by rewarding increasingly close approximations of that behavior until you get the behavior you want. This can help keep a dog motivated when they otherwise might be distracted.

Most hounds and terriers have a strong prey drive, so take extra care when they are around small animals. Many toy breeds have terriers and other working breeds in their backgrounds, so one should never be surprised when a strong prey drive pops up.

A catch-all for a variety of breeds that don’t specifically fit in any of the other groups, the “Non-Sporting” group is quite a misnomer, as quite a few of the breeds so categorized were bred to be working dogs. Dalmatians are a good example of this, and a breed that is near and dear to my heart. I currently share my life with two of them, and they are the greatest Dalmatians most people meet, so I am told.

There’s a reason for that! Originating in Croatia, the Dal has performed various work through the years. They were war dogs that guarded the borders of Dalmatia, and were used to hunt vermin and wild boar, and as gun dogs, trail hounds, circus dogs, and, most notably, as carriage and coach dogs. Affectionately known as “firehouse dogs,” Dalmatians were trained to run alongside fire carriages to protect the horses and guard the firehouse.

It takes a lot of energy and stamina to run with horses for miles, and many today still have that same energy and stamina. Unfortunately, many are not given adequate outlets for that excess energy; my dogs do receive lots of daily exercise, and that’s likely the reason I receive so many compliments. I train them in competitive obedience, rally, and agility, tricks, and even coach-dog training. My dogs run with horses! And when I can’t do this, they run alongside my bike. In addition, they have an opportunity and environment that allows them to play so hard, it’s likely the equivalent of running several miles. These are the necessary activities that result in not only “the most well-mannered Dalmatians” many have ever seen, but also, the most content and happy ones, too!

Get the Dog You Want, Work with What You Get

When it comes to dog selection, it’s similar to picking your significant other: “The heart wants what the heart wants.” Regardless of what breed or type of mixed-breed dog you choose, you can enhance both of your lives if you acknowledge the instincts of his ancestors and focus on constructive ways to work with them, rather than trying to change your dog. Only then can we stop thinking something is “wrong” with our dogs, and start looking for ways to help them become the dogs their genes are telling them to be.

Canine education specialist, dog behavior counselor, and trainer Laurie Williams is the owner of Pup ‘N Iron Canine Fitness & Learning Center in Fredericksburg, Virginia.