For the past few weeks, as I have been working on this issue, I have also been promoting my latest batch of foster puppies to potential adopters, making arrangements for them to come and meet the pups, trying to make the best matches between the puppy candidates and the interested families … and, inevitably, saying goodbye to each darling little puppy face – sending them off with their new families for the start of the best lives I can hope for them, with tears and kisses on the puppy lips.

While doing that emotional work, though, I’ve also been answering questions from the adoptive families: What food should I buy? Do they have to sleep in a crate? How many more vaccinations do they need? How soon can I walk them around my neighborhood?

Then there is the information that I want them to know that is a priority for me – things they have not thought of (yet) but that I know will come up! Stuff like, what sort of collars, harnesses, and leashes to buy (and not to buy), how to housetrain the pups, and why they should have signed up for a puppy kindergarten class already.

No matter how much emailing we have been doing in preparation for puppy pick-up day, there is always something I feel I have missed. For years, I have been saying I need to compile a whole puppy manual that contains answers to every question that adopters have asked me, with all the information that I have learned over the past 24 years from all of WDJ’s contributing writers – who are amazing trainers, veterinarians, and nutrition experts. But the demands of the next month’s deadline arrives soon enough (and sometimes, so does the next litter of foster pups), so that manual just doesn’t get done.

For now, for my most recent puppy adopters, this article, full of references to past articles in WDJ, will have to do. And who wants to read a book anyway? People want short, digestible answers to their most urgent questions, so here’s my best attempt at it.

Q: What’s the secret to housetraining? Start thinking about it on the ride home. Plan to carry the pup from the car straight to the area where you want her to eliminate, and make sure that no other dogs or people are present to distract or intimidate her. And then just wait with her calmly, for as long as it takes for her to “go.” (Prepare yourself to wait to empty your own bladder until your pup has emptied hers!)

The goal is to immediately give her a safe, quiet place where she feels relaxed enough to empty her bladder (and perhaps her bowels) – so when, in another hour, after introducing her to her new home and family, allowing her to drink her fill, and perhaps having a little meal, you take her outside, she will recognize that safe space and, more quickly this time, “go” again. Praise be! And treats, too.

From then on, for the next few days, your job is to shadow your new pup every minute that she is awake – and to whisk her outside at every moment that it appears she might be feeling, er, a little full. That thought will occur to her routinely, within a minute or two after drinking, eating, or waking up from a nap – and then, of course, at random moments in between all that.

The only times you can relax and take your eyes off your pup in these first few days? When she’s outside or enclosed in a crate or small exercise pen – some place that she will be disinclined to make a mess. (I’d add, “or sound asleep,” but puppies have a way of waking up and going pee the moment you step out of the room!)

The secret, if all of this can be boiled down to one sentence, is, from the first minute in your home, to never give her an opportunity to make a mistake and eliminate in your house, to give her many, many opportunities to eliminate outdoors, and to richly reward each of those outdoor successes. (And if she does eliminate indoors, to make every effort to remove every scent-bearing molecule of the urine or feces, so it doesn’t enter her nose to alert her subconscious brain that “It’s time to pee again!” every time she walks by that spot.)

For more about housetraining, see “How to Potty Train a Dog,” July 2018.

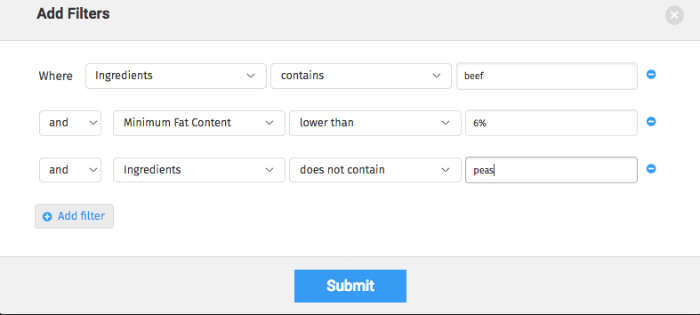

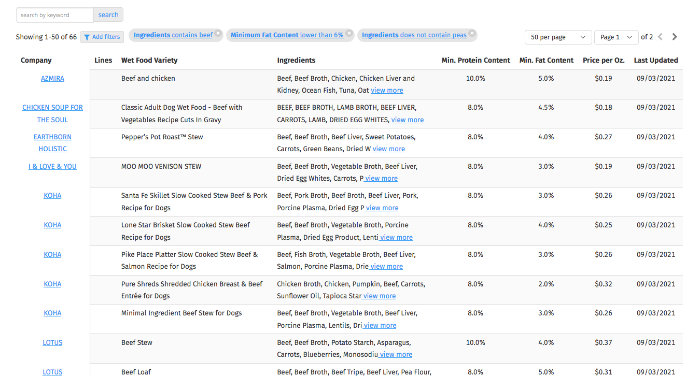

Q: What should I feed her? I’d say, “Find out what she’s been getting fed and start there ….” but in the case of many shelters and rescues, you may not be able to get an answer. And, in any case, you may want to change her food anyway.

The first thing to do is to make sure that you are buying foods that are formulated to meet the needs of growing puppies. Look for the “nutritional adequacy” statement on the bag, a.k.a. the “AAFCO” statement. (It’s called this because it will reference the Association of American Feed Control Officials in the statement.) For puppies, the statement must say that the food meets the nutritional requirements of either “dogs of all life stages” or for “growth.”

Next: As regular subscribers know, I’m a big proponent of feeding dogs and puppies a lot of variety. The more kinds of foods they get, the sturdier their digestion seems to become. I buy small bags for puppies, so I can determine what they like the most and what foods and ingredients best agree with their little digestive tracts. The most critical part of this is to keep track of what you are feeding and how her tummy handled it by noting any deviations from a nice, normal poop.

To keep track of what I’ve fed, I like to cut out the ingredient panel from the foods I am feeding and tape them on the calendar (I write down the name of the food on the start date of each bag, and then do the thing with scissors and tape when the bag is finally empty.)

As to the notes about poop? It doesn’t matter whether you note this in your online calendar program or the calendar hanging on your kitchen wall – just note it! You can’t possibly remember it otherwise. A liquid poo, a trend toward constipation, terrible gas? Make a note.

After a few months, you should start seeing some trends. If she tends to turn up her nose at a particular brand, stop buying it. If fish-based foods seem to give her the runs – cut them out of your rotation. If she vomits a few times each time she’s being fed from a bag of beef-based food, start avoiding beef-based foods! If she gets itchy on certain foods, go back and look at your calendar for clues; what do those itch-correlated foods have in common? It may take time and detective work, but you should start to see trends.

“But wait!”you say. “I’ve always heard that you should switch foods gradually, over the course of a week or more!” Unless your pup is one of those whose digestive tract is very touchy, or who turns out to be allergic to a number of food ingredients, if you switch foods frequently, you should be able to switch foods at the drop of a hat without any reaction at all.

For more about food choices, see “How Long to Feed Puppy Food?” May 2021 and “Puppy Needs New Food!” September 2020.

Q: Should I crate-train her? In my opinion, teaching a dog to be comfortable in a crate is doing them and you a huge favor – if for no other reason than making them feel safe and calm when they have to be crated (in a small cage) at the vet or in an environmental emergency. As a volunteer at my local animal disaster-response group, I have seen how traumatic it is for some dogs who have been separated from their families during wildfires and floods to be held in a crate – and how others accept the containment placidly, fully trusting that their owners will return to let them out at some point. If an earthquake, tornado, flooding, or fire separates you and your dog, may he never be the former, only the latter!

That said, it’s not necessary to start a rigid crate-training protocol on Day 1 in your home – and frankly, I think there are more puppies who get traumatized by a “crate them at all costs!” approach than there are puppies who happily accept this close confinement. I like to see a crate present and in use from Day 1, but with the door open! Let your pup begin to associate it with only good things. Toss treats into the crate, smear some peanut butter on the back wall (if you have a plastic crate), and feed him his kibble in a scatter in there – all with the door open. If it seems like he’s happy hanging out in there, reward him with one of his favorite toys, chewies, or a nice big meaty raw bone.

Of course, it’s nice (and sometimes quite necessary) to be able to secure the pup in an enclosed space to keep him out of trouble for a period of time that’s commensurate with his ability to “hold it.” If your puppy is already completely relaxed and calm about being in the crate with the door closed – well, you’ve hit the jackpot. Don’t abuse this or take it for granted! Don’t make him stay locked in there for too long at first, or his willingness to go in may quickly fade. If, in contrast, he’s still on the fence about being in the crate, and anxious about you shutting the door, don’t rush it! Either invest in a nice, sturdy exercise pen, so he can be contained but not feel quite as trapped. (Or, put him in a small room, like a bathroom or baby-gated kitchen, that you can thoroughly puppy-proof; put up all soaps and cleaners and garbage pails and anything that can be pulled down, such as shower curtains or brooms and mops.)

If you need to leave him alone in his safe confinement area for more than an hour or two, you should also provide him with a legal place to eliminate. Training pads, litter boxes, turf boxes, and even special watertight bathroom boxes are available for this purpose.

Then, as he matures, keep up the crate-training, never over-using it, forcing him into it, or failing to let him out when he’s miserable in there. While many trainers used to say that it was important to wait until a dog or puppy stopped crying or pawing at the door to get out, we know now this approach can (and frequently does) backfire, creating a dog who panics not only when he’s in the crate, but when it appears he’s going to be left home alone at all.

For in-depth advice about crate-training, see “Crate Expectations: What You Need to Know About Your Dog’s Crate,” July 2020.

Q: How do I keep him from eating my socks and chewing on the furniture? The extent of the puppy-proofing that’s necessary varies from pup to pup. I’ve fostered some pups who could be trusted to hang out alone in my office for hours with no crating or puppy-pens whatsoever, despite the availability of multiple electrical and computer cords under my desk and books, magazines, and knick-knacks on shelves all around the room and at puppy-height. In contrast, I’ve had others I couldn’t take my eyes off for a moment without something getting chewed up.

And then there is Exhibit A, my own dog Woody, my only foster-failure (foster puppy that I kept) to date, who spent the better part of his first year chewing on our furniture and parts of the house, for crying out loud. He chewed nearly through a young apple tree trunk in the yard! If it was wood, he would chew it. (I blame my husband for naming him Woody, because he wasn’t chewing wood before he was named that!)

Though I (clearly) wasn’t always successful at it – he was particularly challenging! – I knew how to prevent this:

- Give him a wealth of “legal” chew toys. Determine what textures he likes best – hard plastic, plastic with “give,” meaty bones, bull pizzles, wooly toys, fabric toys, and perhaps, yes, wood – and make sure he has a lot of them. (Finding sticks and pieces of untreated lumber that wouldn’t splinter when Woody chewed them was our hobby for a year or so.)

- Prevent his unfettered access to the things you don’t want him to chew. Use baby gates or doors to keep him out of rooms that can’t be puppy-proofed and puppy pens to protect bookshelves, or to fence off your home office desk so the pup can’t go under and chew on cords. Pick up socks and underwear, put shoes in closets, put the kitchen and bathroom trash under the sink, and so on.

- Every time you catch him with something he’s not supposed to have, don’t yell, admonish, or snatch it away; go find his favorite toy or a handful of particularly delicious treats, and trade him the toy or treats for whatever he has.

This phase will pass, I promise. Woody hasn’t eaten a tree or door frame in years.