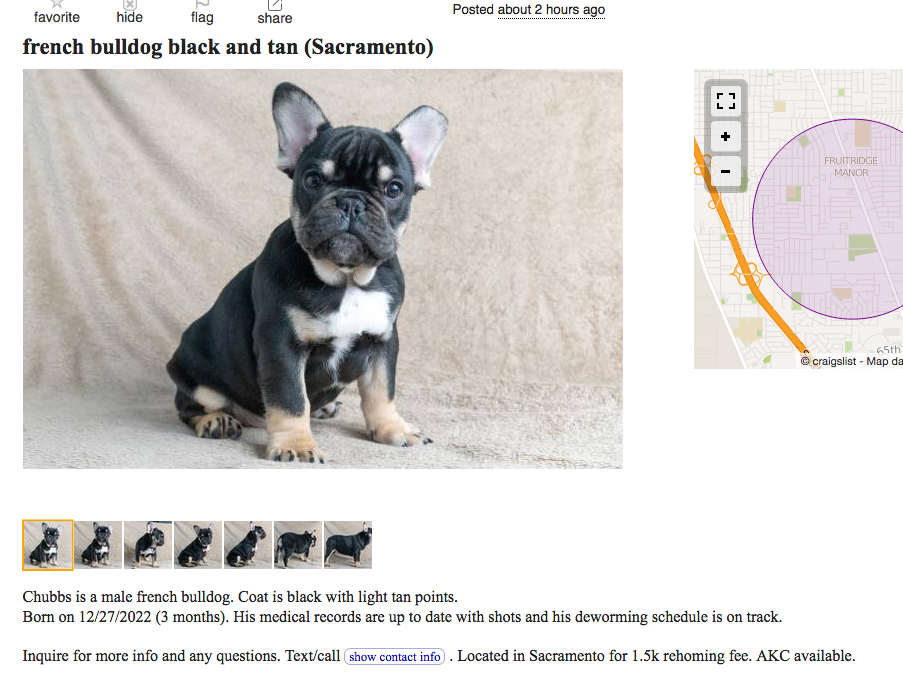

Intestinal blockages (bowel obstructions) are not uncommon in dogs. Usually, the patients are young dogs, because they like to eat dumb stuff! As dogs mature they tend to outgrow this eat-anything behavior, but in the meantime, we must prevent ingestion of said dumb stuff by puppy-proofing our homes, using crates or exercise pens to contain young dogs when we are unable to watch them, keeping socks and underwear picked up and garbage cans out of reach, denying access to kids’ rooms strewn with toys, and so on.

- Ingested foreign material (cloth, plastic, wood, rocks, bones, etc.)

- Tumors

- Polyps

- Granulomas (caused by infectious organisms like pythiosis)

- Scar tissue/adhesions from prior abdominal surgery

- Intussusception (bunched-up intestines)

It’s fairly easy to tell if a dog has a classic intestinal blockage: A previously happy, healthy 18-month-old dog suddenly starts vomiting everything he’s been fed. Initially, he’s still running around, playing, and happy to eat. But every time he eats, he vomits everything within a few hours.

For the first day, he may produce stool, but after a day or two of this, he will start looking like he isn’t feeling well. He will be less active and less interested in food and have decreased or no stool production. Abdominal pain may be expressed by a reluctance to lie down, posturing in a downward dog type of yoga pose, and whining or yelping when his abdomen is touched.

At the veterinarian’s, his bloodwork is all normal, but his x-rays show huge loops of gas-distended bowel. This classic case is a slam dunk – an easy diagnosis. Usually, with immediate surgical intervention, the happy, healthy dog will be back in no time.

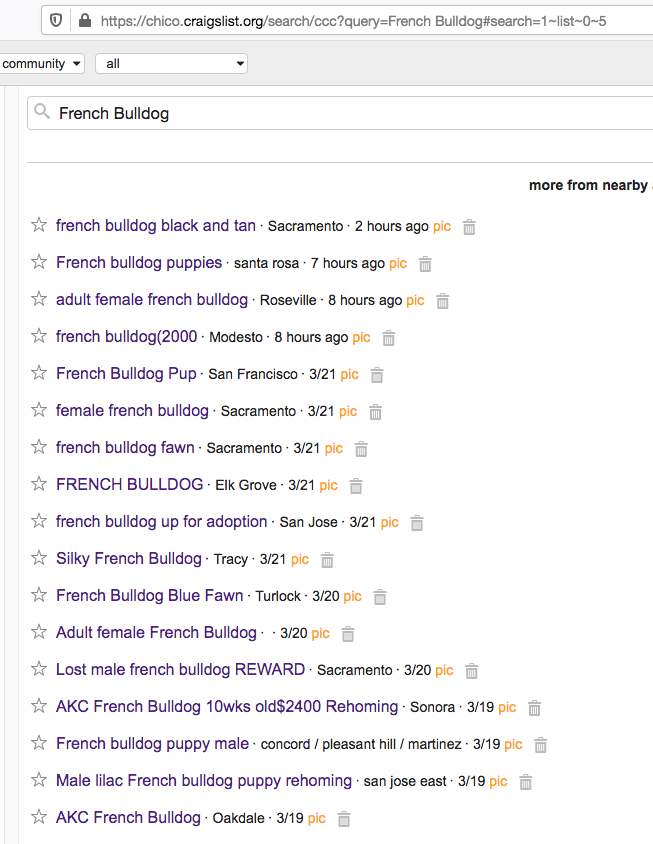

Unfortunately, not all cases are as clear-cut as that. Diagnosing intestinal blockages can be challenging. Symptoms can be tough to interpret, especially with partial blockages. Partial blockages occur with slow-moving foreign material, like a sock or cloth that is trying to make its way through the intestines. Polyps, tumors, granulomas, and scar tissue can also lead to partial blockages.

Partial blockages tend to cause intermittent symptoms of vomiting, loss of appetite, straining to defecate, passage of small amounts of stool, abdominal pain, and lethargy. These symptoms may come and go, and can last for a week or more with slow-moving foreign material. Partial blockages due to slowly growing masses worsen over time. With full blockages, a big hint is that there is literally nothing coming out the back end. Not so with partial blockages.

Complete obstruction:

- Vomiting

- Loss of appetite

- Abdominal pain

- No stool production

- Lethargy

- Weakness

Partial obstruction:

- Intermittent vomiting

- Waxing, waning appetite

- Intermittent abdominal pain

- Intermittent lethargy

- Straining to defecate

- Low stool production

- Diarrhea

- Weight loss

Diagnosis of Intesintal Blockages

Interpreting symptoms of a blockage can be challenging, but ironically, it can be even more difficult to interpret the diagnostic x-rays. Many materials ingested by dogs do not show up on x-rays. Anything cloth or plastic can be difficult or impossible to see. Partial blockages don’t cause the classic gassy distention of the intestines that happens with full blockages. Your vet may recommend repeating the x-rays in 24 hours if there is a suspicion of partial or full obstruction. Looking for changes (or lack thereof) on x-rays can be informative.

Abdominal ultrasound is a useful tool when x-rays are not definitive. Foreign bodies and masses can usually be identified with this modality.

Barium swallows with serial x-rays is another diagnostic tool that can be used to diagnose intestinal foreign material and/or blockages, although this method has been largely replaced with the increasingly easy access to abdominal ultrasound. Barium studies require the dog to be repeatedly x-rayed over six to eight hours, during which a significant volume of liquid is administered to a vomiting dog, risking aspiration of barium into the lungs; abdominal ultrasound is obviously preferable.

If a definitive diagnosis cannot be made with certainty – but there is enough suspicion based on history, symptoms, and x-ray and/or ultrasound results – abdominal exploratory surgery will likely be recommended.

Surgery for Intestinal Blockage or Suspected Blockage

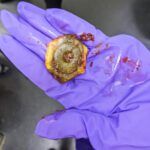

In an abdominal exploratory surgery, all the organs in the abdomen are fully examined, with the gastrointestinal tract being visualized and palpated from the stomach to the rectum. If foreign material is identified in the intestines, it will be removed. Some intestinal blockages require resection (removal) of a length of the intestine if the intestinal tissue has been compromised. Any masses identified may be removed if possible and biopsied.

If nothing abnormal is found, your surgeon will take biopsies of the stomach and intestines to see if some other cause for the symptoms can be identified.

Survival Rates for Intestinal Blockage Surgery

Survival rates are high for young dogs undergoing surgery for intestinal blockages if they are diagnosed in a timely fashion and operated on quickly.

If a blockage goes untreated for too long, the surgery will typically be more complex with serious post-operative complications more likely, making overall survival rates lower for these dogs. Survival rates are also generally lower for geriatric dogs, as cancerous tumors are sometimes the underlying cause for senior dogs, and their ability to heal and fight infection is lower.

Don’t Delay Veterinary Attention

Keep in mind that intestinal blockages are surgical emergencies. The sooner the problem is identified and corrected the better. With full blockages, dogs are generally going to experience significant pain and become seriously ill within a day or two. The pressure from the blockage compromises the blood flow to the intestines, resulting in devitalization of tissue. As the tissue dies, it leaks toxins into the abdomen and the bloodstream.

Without prompt surgery, the intestine will rupture and the dog will die from septic peritonitis. Survival rates for dogs with long-standing (more than two to three days) intestinal blockages are much lower than for those treated right away.

If vomiting is unusual for your dog, starts suddenly and happens repeatedly, don’t wait. If it’s a blockage, the sooner your dog has surgery the better. If a blockage is ruled out, your veterinarian can prescribe medications to make your vomiting dog feel better. It’s a win-win.

An otherwise healthy 5-year-old dog came into the veterinary clinic with a history of several days of intermittent vomiting and not feeling well. Initial x-rays were inconclusive, showing no obvious foreign material and no gas-distended bowel. He was treated for non-specific gastroenteritis and sent home.

Over the next week, the dog continued to vomit intermittently, had a decreased appetite and weight loss, and produced only small amounts of stool. His blood test results were all normal. Repeat x-rays were still unimpressive as far as gas distention of his bowel, but the offending foreign body could finally be seen. At surgery, a hard plastic hexagon-shaped object was removed from the small intestine where it was lodged. The hole in the center of the object allowed the contents of the intestines to pass through, thereby preventing a more easily diagnosed full blockage. He should experience a full and smooth recovery.