You can find them everywhere – at dog parks and doggie daycare centers, in dog training classes, in your neighbor’s yards … perhaps even in your own home. “They” are canine bullies – dogs who overwhelm their potential playmates with overly assertive and inappropriate behaviors, like the out-of-control human bully on the school playground.

Jasper is a nine-month-old Labradoodle from a puppy mill, currently enrolled in one of my Peaceable Paws Good Manners classes. He was kept in a wire cage on a Pennsylvania farm until he was four months old, when his new owners purchased him. Katy Malcolm, the class instructor, asked me to sit in on the first end-of-class play session with Jasper because she was concerned that his lack of early socialization could present a challenge. She was right.

Sam was a 10-week-old Golden Retriever puppy, well bred, purchased from a responsible breeder by knowledgeable dog owners who immediately enrolled him in one of my Peaceable Paws Puppy Good Manners classes to get him started on the right paw. Sam unexpectedly also turned out to be a challenge at his first end-of-class puppy play session.

These two dogs had considerably different backgrounds, but when it came time to play, both dogs exhibited bullying behaviors to other dogs: Jasper because he never had a chance to learn how to interact appropriately with other dogs; Sam because – well – who knows? Genetics, maybe? Early experiences in his litter, maybe? Regardless of the reasons, both dogs required special handling if they were ever to have a normal canine social life.

Is Your Dog Bullying Other Dogs at the Playground?

In her excellent book, Fight!, dog trainer and author Jean Donaldson defines bullying dogs (not to be confused with “Pitbull-type dogs”) as those dogs for whom “roughness and harassment of non-consenting dogs is quite obviously reinforcing.” Like the human playground bully, the bully dog seems to get a kick out of tormenting less-assertive members of his playgroup. Donaldson says, “They engage at it full tilt, with escalating frequency, and almost always direct it at designated target dogs.”

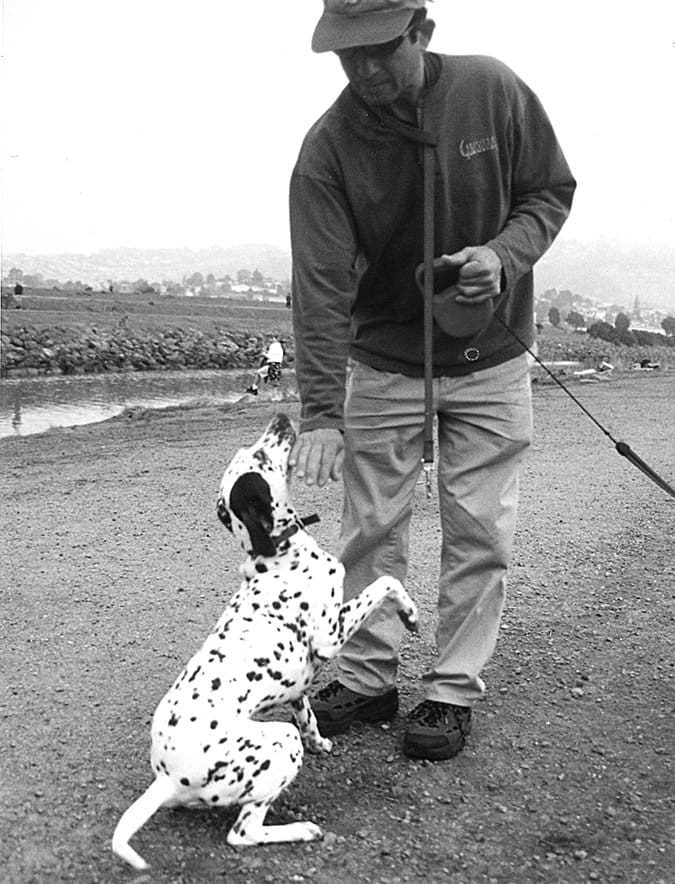

When released with permission to “go play,” the poorly socialized Labradoodle, Jasper, immediately pounced on the back of Mesa, an easy-going and confident Rott-weiler who was playing nicely with Bo, a submissive but exuberant Golden Retriever. Jasper barked insistently, nipping at Mesa’s back as she tried to ignore his social ineptness. Finally, fed up with his boorish behavior, she flashed her teeth at him one time, at which point he decided Bo was a better target for his attentions. Indeed, Bo found him overwhelming, a response that emboldened Jasper to pursue him even more energetically.

We intervened in his play with Mesa several times by picking up Jasper’s dragging leash and giving him a time-out when his behavior was completely unacceptable, then releasing him to “Go play!” when he settled a bit. Each time we released him he promptly re-escalated to an unacceptable level of bullying, until Mesa herself told him to “Back off, Bud!” with a quick flash of her teeth.

Human-controlled time-outs, however, made no impression on Jasper. The canine corrections were more effective, but didn’t stop the behavior; they only redirected it to a less-capable victim. Because Bo wasn’t assertive enough to back Jasper off, we ended the play as soon as Jasper turned his attentions to the softer dog.

Like Jasper’s preferred victim, Sam’s favorite bullying target was also a Rottweiler – not a breed you’d expect to find wearing an invisible “bite me!” sign. Max was a pup about Sam’s own age, who outweighed Sam considerably but was no match for the smaller pup’s intensity.

Sam had given us no indication during class that he had a play problem. In fact, he was a star performer for his clicks and treats. However, when playtime arrived his demeanor changed from an attentive “What can I do to get you to click the clicker?” pupil to an “I’m tough and you just try to stop me!” bully.

Several seconds after the two pups began frolicking together, Sam suddenly pinned Max to the ground with a ferocious snarl, then released him briefly, just to pin him again in short order. Needless to say, we also intervened quickly in that relationship!

What Does Appropriate Dog Play Look Like?

Owners often have difficulty distinguishing between appropriate and inappropriate play. Some may think that perfectly acceptable play behavior is bullying because it involves growling, biting, and apparently pinning the playmate to the ground. Appropriate play can, in fact, look and sound quite ferocious.

The difference is in the response of the playmate. If both dogs appear to be having a good time and no one’s getting hurt, it’s usually fine to allow the play to continue. Thwarting your dog’s need to play by stopping him every time he engages another dog, even if it’s rough play, can lead to other behavior problems.

With a bully, the playmate clearly does not enjoy the interaction. The softer dog may offer multiple appeasement and deference signals that are largely or totally ignored by the canine bully. The harassment continues, or escalates.

Any time one play partner is obviously not having a good time, it’s wise to intervene. A traumatic play experience can damage the softer dog’s confidence and potentially induce a life-long fear-aggression or “Reactive Rover” response – definitely not a good thing!

Some bullies seem to spring from the box full-blown. While Sam had, no doubt, already been reinforced for his bullying by the response of his softer littermates, he must have been born with a strong, assertive personality in order for the behavior to be as pronounced as it was by the tender age of 10 weeks. Jasper, on the other hand, may have been a perfectly normal puppy, but months of social deprivation combined with a strong desire to be social turned him into an inadvertent bully.

There can certainly be a learned component of any bullying behavior. As Jean Donaldson reminds us, the act of harassing a “non-consenting dog” is in and of itself reinforcing for bullies.

By definition, a behavior that’s reinforced continues or increases – hence the importance of intervening with a bully at the earliest possible moment, rather than letting the behavior become more and more ingrained through reinforcement. As with most behavior modification, prognosis is brightest if the dog is young, if he hasn’t had much chance to practice the unwanted behavior, and if he has not been repeatedly successful at it.

How to Modify a Bossy Dog’s Behavior

Successful modification of bullying behavior requires attention to several elements:

• Skilled application of intervention tools and techniques: Leashes and long lines, no-reward markers (NRMs), and time-outs.

• Excellent timing of intervention: Application of NRMs and time-outs.

• Reinforcement for appropriate behavior: Play continues or resumes when dog is calm or playing nicely.

• Selection of appropriate play partners: Dogs who are not intimidated or traumatized by bullying behavior.

The most appropriate human intervention is the use of “negative punishment,” in which the dog’s behavior makes a good thing go away. In this case, the most appropriate negative punishment is a time-out. Used in conjunction with a “no-reward marker” (NRM) or “punishment” marker, this works best for bullying behavior.

The opposite of the clicker (or other reward marker, such as the word, “Yes!”), the NRM says, “That behavior made the good stuff go away.” With bullying, the good stuff is the opportunity to play with other dogs. Just as the clicker always means a treat is coming, the NRM always means the behavior stops immediately or good stuff goes away; it’s not to be used repeatedly as a threat or warning.

My preferred NRM, the one I teach and use if/when necessary, is the word “Oops!” rather than the word “No!” which is deliberately used to shut down behavior – and as such is usually delivered firmly or harshly and unfortunately often followed by physical punishment. “Oops!” simply means, “Make another behavior choice or there will be an immediate loss of good stuff.” An NRM is to be delivered in a non-punitive tone of voice; it’s almost impossible to say “Oops!” harshly.

Timing is just as important with your NRM as it is with your reward marker. It says, “Whatever you were doing the exact instant you heard the ‘Oops!’ is what earned your time-out.” You’ll use it the instant your dog’s bully behavior appears, and if the bullying continues for more than a second or two more, grasp his leash or drag-line (a long, light line attached to his collar) and remove him from play. Don’t repeat the NRM. Give him at least 20 seconds to calm down, more if he needs it, then release him to go play again. If several time-outs don’t dampen the behavior even slightly, make them longer and make sure he’s calm prior to returning to play.

If a half-dozen time-outs have absolutely no effect, end the play session for the day. If the NRM does stop the bullying, thank your dog for responding, and allow him to continue playing under direct supervision as his reward.

Another sometimes-effective approach to bully modification requires access to an appropriate “neutral dog” – a dog like Mesa who is confident enough to withstand the bully’s assault without being traumatized or responding with inappropriate aggression in return. A flash of the pearly whites as a warning is fine. A full-out dogfight is not.

It’s important to watch closely during interactions with the bully. Any sign the neutral dog is becoming unduly stressed by the encounters should bring the session to an immediate halt. A neutral dog may be able to modify your bully’s behavior, and have it transfer to other dogs – or not. If not, you may be able to find one or two sturdy, neutral dogs who can be your dog’s play companions, and leave the softer dogs to gentler playpals. Not all dogs get along with all other dogs.

Say No to Saying “No!”

Dog owners are often puzzled when we suggest they not use the word “No!” with their dogs. “How else,” they wonder, “will my dog know what he’s not supposed to do?”

A dog’s goal in life is to get good stuff, and his mission is to do whatever makes good stuff happen. You can teach your dog what not to do by controlling the consequences of his actions. If inappropriate behaviors consistently make good stuff go away, your dog will stop those behaviors. His goal is to make good stuff happen, not make it go away.

If you’re good at managing your dog’s environment, then he’ll learn to do appropriate things to get good things, without your use of the word “No!” If you’re poor at management, he’ll be reinforced for his inappropriate behaviors, like jumping up on counters or tipping over garbage cans to look for food, and those behaviors will persist. That said, there are plenty of trainers who do use the “No” word, in various ways.

I use it on rare occasions, for extreme emergencies, and when I do it comes out as a loud roar, indeed intended to stop all behavior. When I’m compelled to use it, I always try to pause afterwards, analyze the situation, and figure out where I need to shore up my management and/or training to avoid having to use it in that situation again.

In contrast, trainer and behaviorist Patricia McConnell uses “No!” as a positive interrupt. She teaches her dogs that “No!” means “Come over here for a treat” – no matter what tone of voice is used. When her dogs hear “No!” they happily run to her to see what she has for them, necessarily interrupting whatever inappropriate behavior they may have been engaged in.

If you do still use “No!” as an aversive in your training program, be sure to avoid coupling your dog’s name with the loud, harsh “No!” It takes only a few repetitions of “Fido, NO!!!!” for your dog to start having a negative association with his name – and you absolutely want to preserve the sanctity of your dog’s positive association with his name. “Fido!” should always mean very, very good stuff!

Outcomes

Sam’s owners were exceptionally committed to helping their pup overcome his inappropriate play behaviors. We continued to allow him to play with one or two other sturdy, resilient puppies, using an NRM and his leash to calmly but firmly remove him every time his play intensity increased. We moved him away from the other pups until he was calm, then allowed him to resume his play. By the end of his first six-week class he was playing appropriately most of the time with one or two other pups, under direct supervision. After two more six-week sessions he played well with a stable group of four other dogs, under general supervision, without needing NRMs or time-outs.

The last time I saw Sam was an incidental encounter, at Hagerstown’s Pooch Pool Plunge event. Every year when the city closes its community pool for the winter, they open it up on one Saturday for people to bring their dogs for a pooch pool party. Sam, now a full-grown adult dog, attended the Plunge at the end of Summer 2005, with more than 100 dogs in attendance. His behavior was flawless.

Jasper may have a longer road, but I’m optimistic that he’ll come around as well. We plan to continue having him play with Mesa, as long as she’s handling him as well as she did in last week’s class. Between Mesa’s canine corrections and our time-outs, we’re hopeful that he’ll learn appropriate social skills and be able to expand his social circle to other appropriate dogs. Is there a Pool Plunge in Jasper’s future? We’ll just have to wait and see.

DOG BULLIES: OVERVIEW

1. Watch your dog when he plays with other dogs. Intervene promptly if he’s being a bully – harassing a “nonconsenting” dog.

2. Watch your dog’s playmates, too. Intervene promptly if someone is bullying your dog – if he isn’t having a good time with the intensity level of play.

3. Allow your dog to play roughly with others as long as everyone’s having a good time and no one’s getting hurt.

4. Educate other dog owners about the importance of allowing appropriate play and intervening when a dog is being a bully.

Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, is WDJ’s Training Editor. Miller lives in Hagerstown, Maryland, site of her Peaceable Paws training center.