[Updated January 4, 2019]

The first time I ever noticed booties for dogs advertised in my pet supply catalogs, I laughed out loud. How frou-frou can you get?

I have since realized that there are some very legitimate purposes for dog boots, and have revised my opinion of their usefulness. In fact, the dog boot industry is a highly specialized one, with different styles of boots produced for different purposes.

There are winter boots to insulate your dog’s feet from cold, damp, ice, snow, and salt; summer boots to shield your pup’s paws from the heat of pavement and asphalt, and hiking boots to protect him from the dangers of sharp rock, brambles, burrs, cacti, and foxtails. They can be used to give a tentative dog traction on slippery floors, to prevent scratches on hardwood floors and snags on carpets, and to deter digging. They can prevent chewing and licking of sores, bandages and medications on the dog’s feet. There are even rubber boots that purport to keep your dog’s feet dry in rainy weather.

The biggest dog boot challenge is keeping the little devils on their feet. Dogs don’t have much in the way of ankles, and a well-fitted boot must hug the ankle joint tightly without rubbing, constricting blood flow, or annoying the dog.

The best boots offer a wide selection of sizes to allow for a good fit. The boot should fit fairly snugly while still providing ample room for the dog’s foot. It should slip onto the dog’s foot with relative ease, not slip off until you want it to, and be constructed of materials that are soft enough to conform to the shape of the foot and be comfortable for the dog, yet sturdy enough to stand up to the rigors of vigorous hiking.

Price is always of interest to the cost-conscious dog owner, who can usually find ways to spend any extra cash on new dog toys and more treats. This is one category of product where it doesn’t pay to skimp. For the most part, the cheaper brands of boots are just that – cheap.

The Problem(s) With Dog Boot Sizes

Various companies gauge their boot sizes differently. Some measure from the heel of the pad to the tip of the toe, others include the toenail length in the size (probably a more appropriate measure, since not accounting for the nail could put excess pressure on the toes). A few brands measure size by the dog’s weight – in our opinion an inaccurate system of measurement, since a dog’s weight can vary although his foot size does not.

Anyone who has ever struggled to put shoes on a baby (it’s pointless, but fashionable!) will immediately understand the challenge inherent in putting boots on dogs: They don’t have a clue that a little pushing down movement with their feet would make your job a million times easier. Fortunately, with a little practice, you get better at getting the boots on quickly. Just watch out for those dewclaws, if your dog has them.

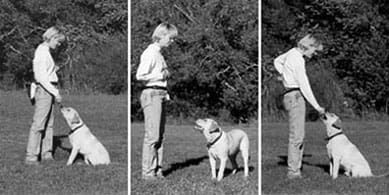

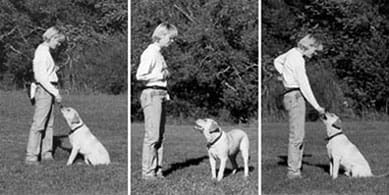

Dogs are unaccustomed to having something attached to their feet, so don’t be alarmed if your canine pal acts like his legs are broken when you first try his boots on him. It can be amusing to watch your dog try to walk without putting his feet down. One of our test dogs tried to take several steps while holding both hind legs off the ground. (It didn’t work.)

Your dog should quickly adapt to the strangeness of shoes on his feet and begin to walk normally again. Be sure to administer plenty of treats when you put boots on paws so your dog learns to happily anticipate their application. If he always wears his boots when he goes for a hike, they will become a reliable predictor of great times, and he will get as excited about seeing them in your hand as he does his leash.

When you first go out with boots on your dog, keep him with you on leash. You may have to readjust the boot straps a couple of times until you get them snug enough to stay on. If Ranger loses a boot when he is deep in the woods you’re not likely to find it again!

Note: Dogs cool themselves by perspiring through their pads. If you are using boots in warm weather, be sure to take breaks and remove the boots from time to time to prevent overheating.

We’ve rated several dog boots on our 0-4 Paws scale based on our observations and preferences. The descriptions should help you determine which product would be the best choice for your dog.

The Absolute Best Dog Boots You Can Buy

We’ll start with our favorites. Muttluks are the Mercedes of the dog boot world and our top choice for winter boots. They exhibit extremely high durability. The sole of the boot is made of water- and salt-resistant leather that stands up well to the elements. The entire boot is stitched with heavy-duty industrial nylon thread, and the Velcro fastener is backed with silver reflective material for nighttime safety and visibility. The larger sizes have a sturdy leather toe-protector (the smaller sizes have Cordura toe-protectors), and the body of the boot is made of soft, heavyweight fleece to cushion the dog’s ankle from the Velcro strap.

Muttluks are available in eight different sizes, from Itty Bitty (smaller than 1.5″ foot) to XXL (4.75″ to 5″). The materials are soft and flex easily with the motion of the ankle. The self-tightening fastening system allows for uniform distribution of pressure around the ankle as well as quick and easy fastening and tightening. The comfortable stretchy leg cuff can be pulled up to protect long legs, or folded down for stubby ones. You can also roll the cuff down over the Velcro strap for extra security. This is the only boot we tested that was at absolutely no risk of falling off.

However, because these boots are made of soft, stretchy materials that fit the foot snugly, and because they are taller than all of the other boots we examined, they are a little harder to put on than some of the other brands. You must hold your dog’s leg while you stretch the elastic cuff and pull it over the foot. It may take some positive reinforcement to get your dog to buy into the process, especially if he is sensitive about having his feet handled.

On the plus side, these boots look just great – the only ones that appear to be made well enough to stand up to serious, long-term use. They are pricey- ranging from $48 to $56 depending on the size, but in our opinion they are well worth it!

The Dog Boot Brands That Aren’t So Great

All of the products in this group are good quality products and reasonable purchases – they just don’t quite measure up to the standard set by the Muttluk. Some are made better, but don’t fit as well. Some have an advantageous design, but aren’t made that well. None of these products puts it all together as well as Muttluk.

Take, for instance, the Velcro Dog Shoes made by Duke’s Dog Fashions of Beaverton, Oregon. Made of tough, flexible Cordura nylon, these boots are well made, but don’t offer as much warmth or insulation as the products designed expressly for extremes of heat or cold. The Cordura material has less give than the fleece used by several other boot makers, and the fit is not as snug or as comfortable. These boots would nominally protect a dog’s feet from mud or rocky terrain, say, but would not offer much in the way of warmth, water-resistance, or traction.

In addition to these shortcomings, the product is available in four sizes only, which limits the accuracy of the fit, and is measured by weight – the least desirable of the measurement methods – up to a maximum of 150 pounds.

In the plus column, the boots appear to stay on reasonably well in the proper sole-down position. Generally, they required only one adjustment after a few minutes of walking to stay securely on the dog. Like many of the boots we found, they are relatively short, which helps them slip onto the dogs’ feet with ease (but may make it easier for them to come off). The simple Velcro strap pulled tight at the ankle and fastened easily. They are also attractive, and available in two-tone colors of red and blue or navy and Kelly green.

As the name suggests, Polar Paws are made to provide protection against cold weather conditions. Made by The Original Polar Paws of Tempe, Arizona, these boots feature a rubberized sole for water-resistance and a slight traction advantage on snow and ice, a Cordura reinforced toe, and a medium-weight soft fleece body. The Velcro fastener features a helpful strap guide on the back of the boot to hold it in place.

Polar Paws are available in six sizes, from Tiny (.75″ to 1.5″) to XL (3.75″ to 4″), and, like all of the short boots, slip onto a dog’s feet easily. The boots seem to flex easily with movement of the dog’s feet, and stay in the correct position, soles down. The boots are attractive, but are available only in red with black toes.

The bad news? These boots didn’t stay on all that well; we had to readjust and tighten the straps after just a few minutes of walking. Also, we found what could be an annoying problem for the dog: In one place, where the inner seam of the boot concludes, the fabric has been melted (in the way that many synthetic fabrics must be cauterized to keep them from fraying) into a sharp edge. This rough knob is above the Velcro tightening strap, so it’s not being forced against the dog’s leg, but we would expect it to rub. This might not be a problem on short walks, but it could definitely cause discomfort on a long walk.

Polar Paws are priced moderately high at $17.95 for all sizes. Though this is high compared to some of the other products we examined, it is not unreasonable considering the quality of the materials used.

Initially, we had less enthusiasm for Cool Paws, the hot-weather version of Polar Paws. (The maker of Cool Paws is listed on the label as The Original Cool Paws; like The Original Polar Paws, this company is also of Tempe, Arizona, so we’re assuming it’s one and the same, and goes by both names.) Cool Paws are made of slightly lighter weight Cordura, in a slightly looser weave. Although the fabric is undoubtedly cooler in hot weather, we found it more likely to snag. Even the package insert warned against using the product in rocky terrain, and keeping the dog’s nails trimmed to prevent puncture of the fabric.

However, it was only after, as instructed, we had soaked the boots in water for several hours that we were able to appreciate the product’s main selling point: The addition of water-absorbing gel beads in between layers of the double sole. The beads swell with water when soaked, then release water over time in the same cooling evaporation action used in other canine cooling products.

Prior to soaking, it seemed to us that the amount of gel beads used in the boots is minimal. We even cut one boot apart so we could examine the gel pack, and we were unimpressed with the tiny amount of beads. But then we took the soaked boots out of the bucket of water we had thrown them in – Wow! Those beads really do swell, forming a cool, cushioned pad under the dog’s feet. Amazingly, the beads don’t squish or ooze water; they simply evaporate and shrink over time as they dry.

Obviously, you wouldn’t use Cool Paws in cool or cold conditions; they are designed specifically for use in hot weather. We don’t know whether there is any research that indicates that cooling pads on a hot dog’s feet really do contribute to lowering or maintaining their body temperature but we can say this: They would definitely protect a dog from burning his feet on hot pavement, sand, or other hot surfaces.

Cool Paws slip onto the foot easily, and the boots are attractive. They are available only in blue with black toe.

After looking at the careful workmanship that went into the preceding products, the first glance at the Nylon Dog Boots made by Scott Pet Products, of Rockville, Indiana (and sold by Valley Vet Supply/Direct Pet Superstore), was a bit of a shock. This is partly because of the product’s simplistic design; the boot is nothing more than a Cordura nylon mitten with a Velcro strap. But the crude look of the product comes from a reversed seam on the upper part of the boot. Such a visible ragged edge and quadruple-sewn seam looks crude. Actually, it makes sense, from the standpoint of the dog whose foot and ankle end up inside that boot. The reversal of the seam also forms a unique pleat at the back of the boot that allows the excess material to fold rather than gather or bunch. It’s an unattractive but comfortable solution to the problem of a seam that could otherwise rub the dog’s leg.

In terms of durability, we have some more concerns. The boots are made of a good quality Cordura fabric (the soles consist of two layers), but the toes are not reinforced. These boots wouldn’t last forever, and they’d provide only a minimum of protection from the elements. We’d expect a product that is targeted toward hunting dogs (they come only in bright orange and only in four sizes) to be tougher.

On the other hand, the boots slipped on easily, and stayed on well if snugly fastened. At $14.25 for all sizes, it’s not a bad buy.

These Boots Aren’t Recommended for Your Dog

The products that we rated with just one Paw are definitely of lesser quality. Their lower prices are attractive, but they just are not durable enough to be considered real hiking boots – they are more like slippers. They might be appropriate for short trips to the backyard, or to prevent licking of wounds or medications on feet. But they really can’t be considered protection from any real weather or rough footing.

Take, for example, the Arctic Fleece Boots made by Ethical Products of Newark, New Jersey and sold by J-B Wholesale Pet Supplies. What the maker calls “Arctic Fleece” is neither; the single-layered material feels more like felt. The strap is elastic (read, prone to stretching and wearing out), with a small square of Velcro sewn onto it. A small circle of vinyl material is sewn onto the bottoms to provide what the maker calls “non-skid” soles – but the vinyl is smooth and could not provide traction. In addition, the boots do not stay in position – the “sole” ends up on top of dog’s foot. Not that it matters; this soft material couldn’t be uncomfortable for the dog in any position.

The Arctic Fleece Boots are available in five sizes by weight, from Extra Small (under 20 pounds) to Extra Large (over 60 pounds). For $5, you get what you pay for.

In another case of a badly named product made by Ethical Products, we found the Waterproof Quilted Boots to be neither, either. The material is “quilted” in only the most generous sense; the outer layer of lightweight nylon fabric is stitched with a quilted pattern, but it doesn’t hold any other layers together. The inner layer is a nylon material so thin that our test dog’s nails caused “runs” from just a few steps around the house. As with the felt boots described above, a circular patch of vinyl (in this case, vinyl with a slight texture) is sewn on the bottom, but no matter; the boots do not stay in position, and the soles generally end up on top of the dog’s feet.

Is there anything nice to say? The synthetic fleece lining around ankles is a nice gesture toward comfort, and the Velcro strap appears appropriately long. The boots slip on easily, and the material is soft. They are available in five sizes, from Extra Small (under 20 pounds) to Extra Large (over 60 pounds). The boots are cute (too cute?), available in red or blue, and cheap at $7.

We didn’t have much use for Pawtectors, either. Made by Pedigree Perfection of Tamarac, Florida and sold by Valley Vet Supply, they are unlike any other boots we saw – perhaps for a reason.

The material Pawtectors are made from is a very unusual composite; it’s a flexible, fully sealed rubberized material on the outside that is soft and fuzzy on the inside. We’ve seen heavy-duty rubber kitchen gloves made of similar material. The top and bottom of the boots are identical; in fact, the packaging suggests turning the boots around when one side gets worn out. It seems durable enough, but it also seems like a dog would get overheated in these boots; there is no breathability to the material.

Also, the unattached Velcro strap is prone to getting misplaced. The rubberized sheath bends with the dog’s motion but doesn’t mold to fit the foot well – there is too much excess material even when boot is fitted according to size chart. And finally, the boots fell off our test dogs several times.

Pawtectors are available in five sizes, from XS (1.75″) to XL (3.75″). They slip on easily, and are available in black or red. At $17 to $22, depending on size, they are no bargain.

Note: This product bears the ASPCA Seal Of Approval, but don’t let that influence your decision. (See “Nonprofit Animal Welfare Groups – Competition for Donation Dollars is Fierce” for more about the Seal of Approval (WDJ, October 2000.)

But our absolute scorn is reserved for the boots made by Four Paws Products Ltd. of Hauppauge, New York. Modeled on “people” boots, this product hardly fits a dog’s foot and ankle anatomy and the strap cannot be tightened enough to stay on. They are essentially “dress up” boots – something you would put on a doll-like dog you hold in your arms. The boots are available in five sizes, XS (1.5″) to XL (3.5″), and available in red or black. The price is low, but entirely too high for a product that is totally useless.

-By Pat Miller