You’ve adopted a new adult dog into your family. Congratulations! As you search for information to help you help your new furry family member adjust to this difficult transition in his life (change is hard!), you may discover that there are lots of resources for new puppy owners, but for new adult-dog owners, not so much. Where do you begin?

We’ve compiled a list of suggestions to help make life with your new dog easier for all concerned. His first few weeks with you set the tone for your lifelong relationship. If you follow these time-tested protocols, you’re more likely to experience smooth sailing – or at least smoother sailing – with your recycled Rover, who may arrive at your door with some baggage from his prior life experiences. We hope you’ve made wise plans and decisions before your new canine pal sets paws through your door for the first time. But even if he’s already camped out on your sofa, it’s not too late to play catch-up with many of the suggestions that follow.

First impressions

Your relationship with your new dog starts forming the moment you first meet. As much as you may want to hug him to pieces, let him set the tone.

Canine social norms are significantly different from primate ones. The things we do naturally – approaching head-on, making direct eye contact, reaching out and hugging, patting on the head – can be very intimidating and off-putting to dogs. Canines are more likely to approach in a curving path, avert their eyes, and sniff flanks before deciding to offer and accept more intimate body contact.

If you want to gain your dog’s trust early in the relationship, let him set the tone for greeting and restrain yourself until you see if he prefers calm greetings or wildly enthusiastic ones. Suggested resource: The Other End of the Leash, by Patricia McConnell. (See page 24 for purchasing information for additional resources.)

I read you

Even after your initial introduction, you can learn a lot about who your dog is by watching his body language.

Does he stand tall and forward in posture, taking everything in stride? If so, he’s likely an assertive, confident dog.

Does his tail wag gently at half-mast and his expression stay soft regardless of what – or who – is going on around him? Then he’s an easy-going, friendly kind of guy.

Does he tend to hang back, looking a little worried, letting someone else take the lead? He’s more timid, lacking in confidence.

Knowing who he is helps you know what to expect from him, and lets you take necessary steps to prevent him from being overwhelmed (or overwhelming others) in new situations. Suggested resource: The Language of Dogs, a DVD by Sarah Kalnajs.

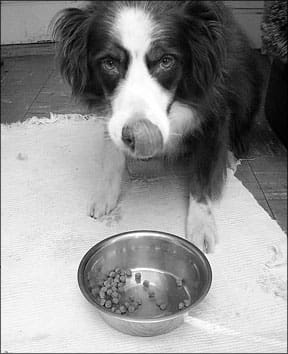

A lost dog’s ticket home

Proper identification is a must for all dogs, and especially for a new dog in your home, who isn’t familiar with the neighborhood and may take off for parts unknown if he manages to escape. Many shelters and rescue groups provide an ID tag of some kind when they hand over the leash to you. Be sure it’s on your dog’s collar from the moment you take possession of him, not in a folder with all his other paperwork.

In addition to a tag with your current address, two telephone numbers, and his name, your new dog should proudly display a current rabies tag and/or license (required by law in most parts of the country). We also urge you to give him some form of permanent identification such as a tattoo and/or microchip.

Collars and tags can be lost or deliberately removed; permanent identification is a little harder to separate from the dog. Suggested resource: “What a Good ID,” Whole Dog Journal October 2001.

See Spot run

Some dogs attach themselves to their new humans almost immediately. I knew on Day Two of Missy’s life as a member of the Miller family that it was safe to allow the eight-year-old Australian Shepherd off-leash on our farm. She had glued herself to me tenaciously; I couldn’t have lost her if I’d tried. However, most dogs take a little – or a lot – longer than that to be trusted with supervised unfenced freedom, especially if you live on a busy road.

Until you’re confident your new dog will come flying when you call even in the face of temptations such as bounding deer, fleeing squirrels, or speeding skateboards, use leashes and solid physical fences to keep the new love of your life close at hand. It could be just a few days to off-leash freedom if he already has a good understanding of coming when called or bonds quickly. It may take a lot longer if he’s never been trained to come, or worse, if he’s poorly socialized and fearful or has learned to run away as part of a delightful game of “Catch me if you can!”

If you’re trusting a solid fence to keep him contained, be sure to check it for holes and weak spots before turning him loose. When you first put him in the yard, watch discreetly from a distance to see if he tries to jump out, dig under, chew through, or otherwise test for weak spots in the fence – or barks nonstop when he’s alone. Don’t let him know you’re watching; he may inhibit his escape attempts until he thinks you’re gone. Note: I do not recommended leaving your dog home alone in a fenced yard; there’s too much that can go wrong without you there to rescue him. Suggested resource: The Really Reliable Recall, a DVD by Leslie Nelson.

Assume nothing

To be on the safe side, assume your new dog has little knowledge or understanding of the mysterious rules of human society. He may or may not be housetrained. He may or may not understand that perfectly good, edible food left in a receptacle (waste can) on the floor of the food-preparation room (kitchen) is not intended for canine consumption. Or that the fresh water in a gleaming white porcelain bowl (toilet) in the little room off the hall (bathroom) is not for drinking. He might not know that stuffed squares of fabric on the sofa (pillows) are for leaning on, not dog toys for chewing, and you may need to teach him that animal skins in your closet (shoes and belts) have a very different purpose than animal skins made into rawhide chews.

Regardless of your new canine companion’s age, treat him like a puppy at first: provide good supervision and management in a dog-proofed home with frequent trips outside to appropriate potty spots until it’s obvious that he understands the quirks and complexities of living with humans. Suggested resource: New Puppy, Now What? by Victoria Schade.

Pawternity leave

It really helps ease the transition for your dog if you can take a few days off work when you first bring him home. Plan ahead and schedule vacation days or personal time off. This will give you time to supervise his activities and find out how much house freedom he can handle, without risking serious damage to your personal possessions. It will also help prevent triggering isolation distress or separation anxiety, giving him a chance to gradually become accustomed to being left alone during a very stressful time in his life.

Dogs who are rehomed multiple times may be more prone to distress over being left alone, as anxiety-related behaviors can be triggered by stress.

During your days off, determine if your dog is comfortable being crated, then leave him alone (crated or not, depending on his response to the crate) for gradually increasing periods over a three-to five-day program, so it’s not a big shock to him when you do go back to work and leave him alone for the day. Make arrangements for mid-day visits, either on your lunch hour or from a professional pet-sitter, until you know he can handle a full day alone at home. Suggested resource: I’ll Be Home Soon, by Patricia McConnell.

House rules

Everyone in the family must agree on house rules ahead of time, and the rules take effect as soon as the dog arrives. Inconsistency is the bane of dog training and management. Dogs do best when their worlds are predictable. If you allow your new dog on the sofa the first week, then Mom yells at him for getting on the sofa when his paws were muddy, and the next day Susie invites him back up to watch television beside her, his world is unpredictable. Unpredictability causes stress, and stress causes behavior problems. I suggest everyone in the family sit down – before the dog comes home – and agree on important questions like:

- Is the dog allowed on the furniture? All furniture, or just some? If just some, which pieces?

- Who will feed the dog? When, where, and what?

- Who will walk/exercise the dog? When and where?

- Who’s doing supervision and potty-training duty?

- Where will the dog sleep?

- Who’s the primary trainer (everyone should participate in training) and what methods and cues will everyone use?

Which other behaviors are going to be reinforced and which ones are not?

When everyone is in agreement, write down the house rules, make copies, and post them in prominent places throughout the house, for easy referral when questions arise.

Remember that training, too, begins the instant your dog walks in the door for the very first time. Every moment you are with your dog, one of you is training the other. It usually works best if you’re training your dog more often than he’s training you. Behaviors that are rewarded in some way will persist and increase. When you give your dog attention, a treat, offer a toy, or engage in a game that he likes, you’re reinforcing/training him to do whatever behavior just preceded that “good thing.”

In addition to your more formal good manners training, which should start within a couple of weeks of his introduction to the family, be sure that the entire family makes “good stuff” happen when your new dog performs desirable behaviors. Conversely, unwanted behaviors make good stuff go away. When he sits to greet you he earns your attention; if he jumps up to greet, turn your attention elsewhere. Suggested resource: The Power of Positive Dog Training, by Pat Miller.

Hello, kitty

Since lots (dare I say the majority?) of animal lovers share their homes with more than one pet, there’s a good chance your new dog will need to get along with other furred, feathered, or finned siblings. Proper introductions will help ensure that those relationships are healthy ones, and that the rest of your nonhuman family members are as happy with your new pal as you are.

Dog-dog introductions are best conducted on safely fenced neutral territory (outdoors is better than indoors), with at least one other set of human hands to manage the other dog. If the dogs indicate a healthy interest in each other from a distance (on-leash) bring the dogs closer. If they continue to appear relaxed and cheerful when they are within 10 feet of each other, drop leashes, and let them greet. Leave the leashes on so you can separate the dogs easily if necessary, but don’t hold the leashes, so you don’t unintentionally create tension in the greeting process.

If at any point you see behavior that makes you think the introduction will be anything but amicable, seek the assistance of a knowledgeable, positive behavior professional to help with the process.

Because dogs are predators and a lot of other companion animals are potential prey (from the dog’s perspective), introductions to other species should be handled with extra care. Always have your new dog on-leash when allowing him to meet new animals, with a good supply of tasty treats on hand. When he notices a cat walk into the room, the fish in an aquarium, a bird chirping in the corner, or goats in a field, feed him bits of yummy treats so he learns to look to you for good stuff in the presence of other animals. If he decides that other animals make good stuff fall from your fingers, he’ll be happier about sharing his home with them.

If he shows any inclination to be predatory toward his nonhuman housemates – chasing or snapping at them – you will need to use scrupulous management to prevent tragedy when you’re not directly supervising, until you convince him that the other animals are more valuable to him as predictors of treats than as prey.

Until you’re completely confident that he won’t hurt them, your dog will need to be safely enclosed in his crate or his own room when you’re not there to observe. If you’re home but not directly supervising, you can use a leash or tether as an additional management option. Suggested resource: “Cats and Dogs, Living Together,” Whole Dog Journal June 2007.

The social scene

An unfortunate number of adult dogs missed out on important socialization lessons. Until you’ve had the chance to observe your dog’s reactions in the presence of a wide variety of stimuli, err on the side of caution and assume that he’s not as well socialized as he could be. Otherwise you could be in for a nasty surprise when you discover that he’s never been exposed to people of other races, tall men with beards, babies in strollers, hikers wearing backpacks, or helmet-wearing bikers. Until you know him well, always have your new dog leashed whenever you’re in an environment where he could encounter something new and strange to him.

If you discover that he has an adverse reaction to novel stimuli, you need to embark on a behavior modification program using counter-conditioning and desensitization to help change his association with new stuff from “Oh no, SCARY!” to “Yay, good stuff!” This process involves keeping him a safe distance from the scary thing, where he’s alert and a little alarmed but not barking, lunging, or otherwise freaking out. The instant he notices “scary thing,” start feeding him a high-value treat (such as tiny bits of chicken), non-stop, until the scary thing leaves.

Keep repeating this until your dog is happy to see “scary thing” at that distance because he realizes that “scary thing” makes chicken fall from the sky. Now move a little closer and repeat the process, until ¡°scary thing¡± right up close still evokes a happy response.

It’s especially important to watch your new dog with children. A fair number of dogs who are otherwise well socialized don’t do well with children, and need either excellent management or extensive behavior modification to make them safe around kids. If your dog is extremely unsocialized or reactive to novel stimuli in general and children in particular, you may need help from a qualified positive behavior professional. Suggested resources: The Cautious Canine, by Patricia McConnell and Help for Your Fearful Dog, by Nicole Wilde.

A little help from your friends

Chances are good that your dog-care professionals will become some of your best friends over the course of your dog’s lifetime. This will include your veterinarian, pet-sitter, groomer, and trainer/behavior consultant. Take the time to find professionals that you like and trust. Make a list of these dog-care providers before you need them – ones who are willing to communicate freely with you; and who share your philosophies of animal care, training, handling, and management. Interview them before you agree to entrust your dog to their care.

A veterinarian should be willing to sit down with you and talk about their perspective on vaccinations and other routine procedures, even if you have to pay for an appointment slot to do so. A trainer should welcome your request to watch one or more of her classes in action. If they’re not willing to be interviewed or observed, they’re not good enough for you and your dog.

Remember that you are your dog’s protector. Don’t ever let anyone talk you into doing anything to your dog – or letting them do anything to him – that you’re not comfortable with. Trust your instincts. Be willing to step forward and rescue your dog from the hands of an animal care professional who would do him harm in the name of training or management. Suggested resources: See “Resources,” page 24 for a list of organizations for training and health professionals.

So there you have it. The list may seem daunting, but it’s intended to prevent you from being overwhelmed by the actual arrival of your new canine family member. Prepare well, help your dog adjust to the overwhelming changes to his world, and get ready to enjoy the rest of your lives together.