Download the Full December 2001 Issue

Make Your Home Healthier for You and Your Animal Companions

A healthy home is a happy home. We can all agree on that.

How can you make your home healthier for you and your animal companions? We can tell you 20 ways, right off the top of our heads. We’ll divide our suggestions into four areas: Cleanliness, Diet, Environment, and Lifestyle.

CLEANLINESS

1. Use safe cleaning agents

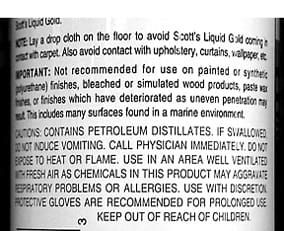

Did you know that most brand-name all-purpose cleaners, bleach, floor wax or polish, glass cleaner, and disinfectant dish soaps contain hazardous materials? Read the list of “cautions” on the back of the labels. These common household agents can cause respiratory problems, damage the nervous system, cause diarrhea, dizziness, kidney and liver damage, and cancer. And effective, safe alternatives are close at hand!

White vinegar can be mixed with water and used to clean glass, porcelain, countertops, and tile. Vinegar can also be mixed with salt to create an all-purpose cleaner. Baking soda can be mixed with water and used to scour tubs and sinks. It can also be sprinkled over carpets to remove odors. When washing vinyl floors, add a few teaspoons of vinegar to the wash water to remove waxy buildup; a capful of baby oil added to the rinse water will polish the floor.

Today, there are also a number of safe commercial cleaning products available; look in your local health food store.

2. Vacuum frequently

A powerful vacuum is a pet owner’s best friend. A model with strong suction and multiple attachments can not only help you keep the sofa, the rug, and your going-on-a-date outfits dog-hair-free, but also prevent fleas from completing their life cycle in your home. Okay, not all dog owners care about dog hair on everything they own. But everyone hates fleas.

Fleas spend only a portion of their time on the dog, and their eggs, larvae, and pupae are likely to be found in any area where the dog lives. Female fleas are prolific, laying as many as 20 to 50 eggs per day for as much as three months. Development of the larvae that hatch out of the eggs takes place off the dog, usually on or near the dog’s bedding and resting areas. Concentrating your efforts on removing the opportunities for the eggs to develop is the most effective population control strategy.

The best way to remove the eggs’ opportunities to develop is to remove the eggs, and to this end, your vacuum will be your most valuable tool in the flea war. Vacuum all the areas that your pet uses frequently, at least every two to three days. Since fleas locate their hosts by tracing the vibration caused by footsteps, vacuuming the most highly-trafficked hallways and paths in your house will be most rewarding. Don’t forget to vacuum underneath cushions on the couches or chairs your dog sleeps on. Change vacuum bags frequently, and seal the bag’s contents safely in a plastic bag before disposing.

For more information, see:

Flee, Evil Fleas: June 1998

3. Wash your dog’s bed

Flea eggs and developing flea larvae cannot survive getting wet. We can presume that any dog who has fleas will have flea eggs in his bed (since fleas usually lay their eggs off the dog). So, if fleas are a problem in your neck of the woods, wash his bedding as frequently as possible. It is not necessary to use bleach, or insecticidal or detergent soaps, all of which can irritate the dog’s skin; plain water will kill the eggs and larvae.

If you can’t wash the dog’s entire bed, at least wash the floor underneath the bed as often as you can. Purchase several covers (or sheets, or towels) for the bed and rotate them in and out of the wash.

4. Wash food and water bowls daily

Washing your dog’s food and water bowls with soap and hot water will not only make them look better and make the dog’s food and water more attractive to him, but also will kill any harmful bacteria that may attempt to grow there. If you feed your dog raw meat, it is imperative that you wash his bowls well daily, even if they look clean from his attentive licking. Pathogenic bacteria present on raw meat can quickly reproduce to harmful levels at room temperature.

While we’re on the topic, the safest bowls are stainless steel. Some ceramic bowls may allow chemicals to leach into the dog’s food and water. And plastic bowls can contain a number of carcinogenic substances.

For more information, see:

The Meat of the Matter, January 1999

The Dish on Dishes, August 1998

DIET

5. Feed your dog the best food

Advocates of homemade diets have a saying, “You can pay for fresh real food now, or you can pay the veterinarian later.” Dogs have thrived on our table scraps for thousands of years; eating what we eat is good for them – as long as what we eat is healthy! If you can, feed your dog a homemade diet that includes fresh meats; fresh, raw bone (ground or whole, as you deem safe); and fresh or lightly steamed vegetables; with occasional additions of grains, dairy products, eggs, fish, and fruit.

If you can’t see your way clear to feeding your dog “real” food, feed him the best quality kibble or canned food you can afford. Supplement the commercial food with occasional healthy treats from your table – and not the unhealthy chunks of fat cut off of your steak, nor old, smelly food from the back shelf of the refrigerator. Add some of the leftover steamed vegetables to his dinner. Make a little extra brown rice or oatmeal and mix it into his breakfast.

For more information, see:

Eat Your Vegetables, October 1998

Bones of Contention, September 2000

Starting Out Raw, December 2000

Best Dry Dog Foods, February 2001

It’s How You Make It, March 2001

Top Canned Foods, October 2001

6. Feed only healthy treats

Just like us, dogs are better off eating healthful snacks that are packed with vitamins, rather than loading up on sugary, fatty treats that are dyed with artificial colors and preserved with artificial preservatives. Chunks of fresh fruit make great snacks for dogs; many enjoy crunching crisp cubed apples, or munching on grapes, papaya, or banana slices. A raw carrot makes a great chew toy, and helps the dog keep his teeth clean. Dogs who prefer meaty treats will jump through hoops for dried salmon or beef.

For more information, see:

There IS a Difference, September 2001

7. Provide fresh, clean water

It’s not enough for dogs to have a bowl full of water at their disposal at all times – they should have a clean bowl full of fresh, pure water at their constant disposal.

Many people fill the dog’s bowl only when it’s bone dry, and fail to wash it out until it turns green with algae. For shame! Dogs drink more when they have fresh water and for normal, healthy dogs, drinking water is a good thing. Water helps regulate all the body’s systems.

At least two or three times a day, dump out the water in your dog’s bowl (you don’t have to waste it – you can use it for the houseplants) and refill it with fresh water. Once a day, wash the bowl out with hot, soapy water.

ENVIRONMENT

8. Provide Non-slip surfaces

Whether they are polished wood or shiny vinyl, the smooth, glistening floors that most of us aspire to own pose certain risks to certain dogs. Dogs who are arthritic or who have suffered physical injuries can really hurt themselves by slipping on slick floors. For these dogs, use carpet or sisal-grass runners in hallways or other areas where your dog needs traction. Surround his food and water bowls with a rubber-backed rug so he can lower his head to eat or drink without his hind legs slipping out from under him.

9. Don’t smoke around your dog

You already know you shouldn’t smoke, for your own health. But did you know that second-hand smoke has been associated with lung and nasal cancer in smokers’ dogs?

Studies conducted at Colorado State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and Biomedical Sciences showed that dogs who live with smokers are more likely to have cancer than dogs that live with non-smokers. Long-nosed dogs with nasal cancer were 2.5 times more likely to live in smoking households than among non-smokers. Short-nosed dogs with lung cancer were 2.4 times more likely to live with a smoker.

If you must smoke, do it outside, and away from your dog. Don’t smoke in an enclosed space such as a closed room (or worse, a car) that has your dog in it.

10. Keep emergency numbers handy

Every phone in your house should have a list of emergency numbers next to it: emergency services, your doctor, dentist, and close family members or friends. If you own a dog, that list should also include the number for your veterinarian, holistic practitioners, all-night and weekend emergency clinic, and poison control center. You should also list numbers for a couple of your dog-loving friends, people who could enter your house and care for your dog if something happened to you. If you travel with your dog, make sure you also have these numbers with you. You don’t want to be scrambling for any of these in a real emergency.

11. Preserve air quality

As we discussed in detail recently, the air in the average home is 2-20 times more polluted than the air outside. It’s not unheard-of for the concentrations of dangerous air pollutants in homes to rise to 100 times the concentration outdoors! And even low concentrations of volatile chemicals can cause chronic or acute illness, cancer, and even genetic mutations in humans and their companion animals.

Dogs are particularly at risk. Many common solvents are heavier than air; they sink to the floor level, where our dogs spend most of their time. And dogs have a faster respiratory rate than we do; pound for pound, they end up breathing more “bad air” than we would in the same environment.

There are many ways to improve the air in your home. Limit (better yet, eliminate) petroleum-based products in your home; all of these substances release health-damaging chemicals into the air. Use natural cleaning products. Open the windows in your home at least once a day, for enough time to really fill the place with fresh air. Place non-toxic houseplants throughout your home; they improve air quality by removing carbon dioxide and releasing oxygen. Don’t use chemical “air fresheners” in your home; use scented flowers or dried herbs to lend a harmless perfume to your home instead.

For more information, see:

No Room to Breathe, October 2001

12. Handle air pollutants carefully

If you were as familiar as toxicologists are with the health effects of indoor air pollution, you really wouldn’t consider bringing home most, if not all, commercial housekeeping or yard chemicals. Say there is a potentially dangerous product – a mineral spirits paint remover, for example – that you deem necessary to use in a home improvement project. Do a little homework, and see if there is a safer alternative (there usually is). If you just can’t (or won’t) find an alternative, at the very least, take the following precautions:

Buy just the amount you think you will need for the project. Schedule the activity so that it occurs when the weather is mild enough for you to thoroughly ventilate your home while the product is in use and for at least a couple of weeks afterward. Keep the product’s container closed every moment it is not being used. Keep all pets (and children, pregnant women, and other vulnerable individuals) away from the area where the product is in use) for this period of time. And then dispose of the remains of the product in a safe, legal manner (following instructions on the label) as soon as possible; once unsealed, most containers are not completely vapor-proof.

13. Pick up poo

We all know that poop smells bad – yes, even your dog’s poop. It also attracts flies and can spread worms. (The larvae of tapeworms, hookworms, and roundworms are all expelled in an infected dog’s feces. Any dog, or person, for that matter, who comes into skin or mouth contact with larvae-contaminated feces can become infected with the worms.) Ideally, everyone would pick up their dog’s feces daily. This would prevent worms, coprophagia (dogs who eat their poo, eww!), dirty looks from neighbors, and delays for emergency shoe-cleaning.

14. Keep a first-aid kit handy

Just as you plan and prepare your dog’s daily meals and training, advance planning and preparation for the unthinkable accident may help save your dog’s life during the critical time between the beginning of the emergency and access to veterinary care.

The time to plan, obviously, is before your dog is involved in an accident. Start gathering the contents for a first aid kit today. A good holistic first-aid kit might contain Rescue Remedy (or another brand of the flower essence remedy) for shock; gauze pads; cotton; tape; Q-tips; pure water (distilled or spring water); a clean glass or plastic spray bottle; elastic bandages; adhesive tape; tweezers; scissors; hydrogen peroxide; soap (castile or other natural type); and herbal cleansing solutions (calendula and hypericum are miraculous).

For more information, see:

Dealing with Injuries, June 1999

15. Chew-proof the house

Not all dogs are apt to chew on weird, random things around the house when they are bored and unsupervised, though some are. All puppies have this proclivity.

If your dog is a chewer – again, we know that all puppies are – he should not be left unsupervised in any room where there are items that could be dangerous if chewed. This includes exposed electrical cords, clothing items or shoes, electronic items (cameras, remote controls, cell phones, etc.), and just about any toys. When left unattended, vulnerable individuals should be safely confined to a crate or puppy pen.

16. Keep your yard “green”

Don’t use pesticides in your yard. Ever. These virulent chemicals can cause every sort of illness known to man and dog. And there are plenty of safe, organic compounds that can help you control pests and keep your lawn and garden healthy without pesticides.

For more information, see:

Toxic Lawns, May 2001

LIFESTYLE

17. Balance quiet time and busy time

Those of us who lead chaotic lives tend to dream of and crave days of quiet, restful sleep. People who are housebound and depressed can benefit from activity and stimulation. Balancing rest and action gives the body the opportunity to stress and then rebuild tissues, and lends the individual a healthy ability to cope with whatever life throws his or her way.

Dogs are no different. Some lead incredibly stressful, busy lives, and could use more rest – dogs who go to work with their owners, for instance, may benefit from a few hours a day of protection from noise and visitors. Dogs who are understimulated will benefit from mild physical exercise and mental challenges.

For more information, see:

Stressed Out? January 2000

18. Exercise. period

Exercise is good for all dogs – within reason, and within the dog’s abilities. As always, balance is key. An extremely long run or vigorous romp at the dog park on a daily basis may excessively stress the dog’s joints and muscles, and deny him the opportunity to repair damaged tissues, resulting in stress fractures, arthritis, or strained muscles or ligaments. Strenuous workouts such as these should be limited to three to four days a week, even for healthy, fit dogs. Alternate hard workouts with shorter, easier exercise sessions, such as walks or short backyard play sessions.

There are far more dogs receiving too little exercise than dogs who get too much, however. Many people with old dogs, super-fat dogs, or dogs with physical handicaps feel that it’s cruel to “make” their dogs go for walks. But the more muscle tissue and coordination the dog has, the better – and he’ll lose both if he’s not at least walking a little, a few times a day.

For more information, see:

Spring Into Better Health, April 2001

19. Socialize

Dogs and humans are social; loners are aberrations, not the rule in either species. Dogs and humans should be able to greet each other happily, communicate well, and part easily from their friends. We all want our dogs to be safe and comfortable with other people, so it’s well worth the effort to properly socialize your dog to canine and human visitors to your home. Ask any friend who stops by to feed your dog a handful of treats, one at a time, to help your dog understand that strangers can be a good thing. Use a tether or baby gate to keep an over-exuberant or over-protective dog from unseemly behavior. Arrange occasional play dates with healthy dogs with compatible temperaments.

For more information, see:

Kid-Proof Your Dog, October 1999

Canine Social Misfits, February 2000

Plays Well With Others, March 2000

20. Spend quality time together

We know it sounds hokey, but human/canine relationships are not much different from human/human relationships. Most of us want dogs who like and trust us and whom we like and trust. We want to be able to take them places without them embarrassing us, and we’d like to be able to have friends come over without having to apologize for our canine partners’ behavior. We want them to pay attention to us! And we want them to understand what we are trying to tell them and to comply with most of our requests without us yelling or repeating ourselves.

Ask Oprah: The health of every relationship depends on the individuals spending time together – and not just on infrequent weekends, and not just laying around watching TV! Take up a hobby together: walking, squirrel chasing, agility, flyball. Work on honing your communication skills. Teaching your dog new tricks is a great way to bond, improve his manners, entertain you, and impress your friends. The more time you spend playing with your dog, training your dog, or just lying around petting or massaging your dog, the better your relationship will be.

For more information, see:

Canine Counseling, March 2001

How to Teach Your Dog to Eliminate on Cue

The term “housebreaking” grates on my sensibilities like fingernails on a blackboard. What is it that we are supposed to break? This term is deeply rooted in the forced-based philosophy of dog training, and immediately gives new dog and puppy owners the wrong mind-set about the process of teaching their dog to urinate and defecate in appropriate places. We are housetraining, not housebreaking, I gently remind my human students and fellow dog trainers when they slip and use the old-fashioned phrase. Breaking implies punishing the pup for pottying in the wrong spot. Training focuses the client on helping the puppy do it right.

A 3-Step Formula for Training Behavior

Housetraining is simple. You don’t give your puppy the opportunity to make mistakes. You do give him plenty of opportunities to do it right. Simple, however, does not necessarily mean easy. It means making a commitment to manage your pup’s behavior 24 hours a day, until he is old enough to be trusted with his house freedom for increasingly long periods of time.

I teach my clients a basic three-step formula for training or changing a behavior. By applying each of these steps you can get your dog to do just about anything that he is physically and mentally capable of, including housetraining.

Step One: Visualize the behavior you want. Create a mental image of what you want your puppy to do and what that looks like – in this case, to consistently and reliably go the bathroom outside in his designated toilet spot. You need to be able to imagine how this looks in order to be able to train your pup to do it. If you only envision your puppy making mistakes in the house, you won’t have the creativity you need to help him do it right.

Step Two: Prevent him from being rewarded for doing the behavior you don’t want. A reward doesn’t have to come from you in order to be reinforcing to your dog. It is very rewarding to a puppy with a full bowel or bladder to relieve the pressure in his abdomen. If you give him the opportunity to go to the bathroom in the house, that will feel good to him, and he will keep doing it when he has the opportunity. It will eventually become a habit, and then his preference will be to eliminate in the house. Step Two requires you to manage your pup’s behavior so he doesn’t have the opportunity to be self-rewarded by going to the bathroom in the house.

Step Three: Help him do it right and consistently reward him for the behavior you do want. This is the step that often gets skipped. You need to go outside with your puppy and reward him when he performs. If you toss him out in the back yard and don’t go with him, you won’t know if he went to the bathroom or not. Coming back in for a cookie may be more rewarding to him than relieving his bladder, so he waits by the back door, comes in, eats his cookie, and then pees on the rug.

You’ll notice that none of the steps involve punishing the puppy for going to the bathroom in the house. Old-fashioned suggestions like rubbing his nose in his mess or smacking him with a rolled-up newspaper are inappropriate and abusive. They teach your pup to be fearful of relieving himself in your presence, and are very effective at teaching him to pee behind the bed in the guest room where you can’t see and punish him. Besides, it is much easier to teach your puppy to go to the bathroom in one right place than it is to punish him for going to the bathroom in an almost infinite number of wrong places.

If you do “catch him in the act,” simply utter a loud but cheerful “Oops!” and whisk him outside to the proper place. Remember to treat the “oops” spot thoroughly with an enzyme-based cleaner designed to remove all traces of animal waste, such as Nature’s Miracle.

Finally, if you really feel you must make use of that rolled up newspaper, smack yourself in the head three times while repeating, “I will supervise the puppy more closely, I will supervise the puppy more closely, I will supervise the puppy more closely!”

The eight-week house-training program described below is the one that I provide to my clients for an eight-week-old puppy. Many dog owners are amazed by how simple housetraining can be, as well as by the fact that their dogs can be trained to go to the bathroom on cue, in a designated spot.

You will need a properly sized crate; a collar and leash; treats; poop bags; time and patience. A puppy pen, tether, and fenced yard are also useful. (For more information on using these tools, see “Getting Off to the Right Start,” January 1999 and “Tethered to Success,” April 2001.)

If you are starting with an older pup or an adult dog, you may be able to accelerate the timeline, since an older dog is physically able to “hold it” for longer periods than a young pup. If, however, at any point in the program your furry friend starts backsliding, you have progressed too quickly. Back up to the previous week’s lesson.

Effective 8-Week Housetraining Program

Week One: Acclimate your puppy to his crate on his first day in your home, off and on all day (see “Crate Training Made Easy,” WDJ August 2000). While you do this, take him outside on his leash to his designated potty spot every hour on the hour. When he obliges you with a pile or a puddle, tell him “Yes!” in a happy tone of voice (or Click! your clicker), and feed him a piece of cookie.

Pick up his water after 7:00 pm to prevent him from tanking up before bed (later if it is very hot), then crate him when you go to sleep.

Most young puppies crate train easily. The crate should be in your bedroom so your baby dog is not isolated and lonely, and so you can hear him when he wakes up and tells you he has to go out. Do not put him in his crate on the far side of the house. He will feel abandoned and lonely and cry his little heart out, but worse than that, you won’t hear him when he has to go – he will be forced to soil his crate.

A successful housetraining program is dependent on your dog’s natural instincts to keep his den clean. If you force your puppy to soil his crate you break down that inhibition and make it infinitely harder to get him to extend the “clean den” concept to your entire house.

When he cries in the middle of the night, you must get up (quickly), put him on his leash and take him out to his potty spot. Stand and wait. When he starts to go, say “go potty!” or “do it!” or “hurry up!” or whatever verbal cue you ultimately want to use to ask him to go to the bathroom. If you consistently speak this phrase whenever your pup starts to urinate or defecate, you will eventually be able to elicit his urination or defecation, assuming, that is, that he has something to offer you at the moment. Being able to put his bathroom behavior on cue is an added bonus of this method of housetraining, and a very handy one when you’re late for a date, or it’s pouring rain or freezing cold outside!

As soon as your pup has eliminated, tell him “Yes!” in a happy tone of voice and feed him a bit of cookie, praise him, tell him what a wonderful puppy he is, then take him in and put him back in his crate. No food, no play, and no bed-cuddling. If you do anything more than perfunctory potty-performance in the middle of the night he will quickly learn to wake you up and cry for your attention.

First thing in the morning, take him out on leash and repeat the ritual. If you consistently go out with him, on leash, you will teach him to use the designated spot for his bathroom. If you just open the door and push him out, he may well decide that two feet from the back door is far enough, especially if it’s cold or wet out. For the first week or so, if his bladder is too full to make it safely out the door, you can carry him out, but by the end of the second week he should be able to walk to the door under his own power.

Now you can feed your puppy and give him his water bowl, but be sure to keep him right under your nose. If you have to use the bathroom, he goes with you. If you want to sit down to eat breakfast, he’s on his leash under your chair, or tethered by his pillow. Ten to 15 minutes after he is done eating, take him out again, repeat your cue when he does his thing, and Yes!, treat and praise when he is done. Also take him out immediately upon the completion of any exuberant play sessions, and whenever he wakes up from a nap.

For the rest of the day, take him out every hour on the hour for his potty ritual, as well as 10 to 15 minutes after every meal. The remainder of the time he must be under your direct supervision, or on a leash or tether, in his pen or in his crate, every second of the day. Judicious use of closed doors and baby gates can keep him corralled in the room with you, but you still need to watch him. If your puppy starts walking in circles or otherwise looking restless, toss in an extra bathroom break.

“But wait!” you cry. “I work all day, I can’t take him out every hour on the hour.”

Ah, yes, that is why housetraining is simple but not always easy. “Home alone” pups are more likely to end up stuck out in the back yard, where they get left for convenience sake as the housetraining program drops lower and lower on the priority list. If you haven’t yet acquired your pup and you aren’t going to be a stay-at-home Mom or Dad, seriously reconsider the possibility of adopting an older dog who is already housetrained and who may be in desperate need of a home.

If you already have your pup, you will need to either find a skilled and willing puppy daycare provider, or set up a safe, puppy-proofed environment with wall-to-wall newspapers or pee pads, and recognize that your housetraining program will probably proceed more slowly. You cannot crate him for the eight to 10 hours a day that you are gone – you are likely to destroy his den-soiling inhibitions, cause him to hate and fear his crate, and possibly trigger the onset of separation anxiety.

When you are home, be extra diligent about your housetraining protocol, and as your pup starts to show a preference for one corner of his papered area you can start slowly diminishing the size of the covered space. You will eventually have to add the step of teaching him not to go on papers at all, which is one of the reasons many trainers don’t recommend paper training – you are, in essence, teaching him that it is okay to go to the bathroom in the house, and then later telling him that it is not okay.

Week Two: Continue crating your puppy at night. Some pups are sleeping through the night by Week 2. Others need nighttime breaks for a few more weeks. During the day, continue to take him out immediately upon waking, 10-15 minutes after each meal, and after play and naps.

You can now begin teaching him to associate “getting excited” behavior with going out to potty. This will eventually translate into him getting excited to let you know he has to go out. If you want him to do some other specific behavior to tell you he has to go, such as taking a bow, or ringing a bell, start having him do that behavior before you take him out.

By now, you should be able to tell when your puppy is just about to squat in his designated place. Say your “Go pee!” cue just a second or two before he starts, so that your verbal cue begins to precede, rather than follow the behavior.

Stretch his bathroom excursions to 90 minutes apart, and start keeping a daily log – writing down the time, whether he did anything outside, and if so, what he did. Make note of any housetraining mistakes – when and where they occurred. While an occasional “Oops!” may be inevitable (we are only human, after all), if you are having more than one or two accidents a week you are not supervising closely enough or not taking him out enough. The log will help you understand your puppy’s bathroom patterns over the next few weeks, and tell you when you can trust him for longer periods.

Week Three: Crate your puppy at night. (I keep my dogs crated at night until they are at least a year old, and until I am totally confident that they can be trusted to hold their bowels and bladder and keep their puppy teeth to themselves.) During the day, try stretching his bathroom intervals to two hours, still remembering to take him out after all meals, play sessions, and naps.

Continue to keep your log, to make sure your pup’s housetraining program is on track. This is especially helpful for communication purposes if two or more family members are sharing puppy-walking duties.

Also continue to elicit the desired bathroom signal behavior before you take him out, and to use your bathroom cue outdoors, prior to the actual onset of elimination. Over the next few weeks, the verbal cue will begin to actually elicit the behavior, so that you can bring his attention to the business at hand when he is distracted, when you are in a hurry, or when you are in a new place where he isn’t sure he is supposed to pee.

By the end of this week, your puppy should be leading you on his leash to the bathroom spot. Look for this behavior as an indication that he is making the connection to the spot that you want him to use.

Week Four: Crate your puppy at night. Assuming all is going well, stretch daytime intervals to three hours, plus meal, play and nap trips. Go with him to his fenced-yard bathroom spot off-leash, to confirm that he is going there on his own, without you having to lead him. Continue to keep your daily log, and reinforce your “outside” and “bathroom” cues.

Weeks Five-Eight: Keep crating your puppy at night. Gradually increase the time between bathroom breaks to a maximum of four hours, plus meals, play, and naptime. You still need to go out with him most of the time, but you can occasionally send him out to his bathroom spot in his fenced yard all on his own, watching through the door or window to be sure he goes to his spot and gets the job done. By this time, accidents in the house should be virtually nonexistent. As long as the program is progressing well, you can begin phasing out your daily log. As your pup continues to mature over the next eight months, he will eventually be able to be alone left for up to eight hours at a time, perhaps slightly longer.

At that point, you can break out the champagne and celebrate – you and your puppy have come of age!

Housetraining Tips and Reminders

1. If your housetraining-program-in-progress relapses, back up a week or two in the process and keep working from there. If that doesn’t resolve the problem promptly (within a day), a trip to the vet is in order, to determine if there is a medical problem, such as a urinary tract infection, that is making it impossible for your puppy to hold it. The longer you wait, the more ground you have to make up.

2. If your pup has diarrhea, not only is it impossible for him to comply with housetraining, he may also be seriously ill. Puppies can dehydrate to a life-threatening degree very quickly. Contact your veterinarian immediately.

3. If your-paper-trained pup refuses to go on anything other than paper, take a sheet of newspaper or pee pad outside and have him go on that. Each subsequent trip, reduce the size of the fresh sheet of paper or pad until it is gone.

4. If your dog’s inhibitions against soiling his den have already been damaged, you may need to remove his bedding from his crate – it is possible that this is now his preferred substrate. Try the bare crate floor or a coated metal grate instead, and set your alarm to wake you up at night as often as necessary to enable you to consistently take him out before he soils his crate.

5. Neutering your male dog between the ages of eight weeks and six months will minimize the development of assertive territorial leg-lifting. Already existing territorial leg-lifting can be discouraged as part of a complete housetraining program with the use of “Doggie Wraps,” a belly band made for this purpose (available from pet supply stores and catalogs).

6. If at any time your reliably housetrained dog begins having accidents in the house, have him examined by your veterinarian in case there is a physical cause.

7. Remember that drugs such as Prednisone can cause increased water intake, which causes increased urination. If it is not a medical problem, evaluate possible stress factors and return to a basic housetraining program.

8. Vigorous exercise can also cause excessive water intake and subsequent urination, as can a medical condition known as polydipsea/polyurea, which simply means drinking and urinating too much.

9. When your dog has learned to eliminate on cue, start asking him to poop and pee on various surfaces, including grass, gravel, cement, and dirt. Dogs can easily develop a substrate preference – grass, for example – and may refuse to go to the bathroom on anything but their preferred surface. If you are ever in a location where there is no grass, you and your dog could be in trouble.

10. If your situation is such that your pup must constantly be asked to wait to go for longer periods than is reasonable, consider litter box training. Lots of people do this, especially those with small dogs and those who live in highrise apartments. This also resolves the substrate-preference problem.

If Your Dog is Ever Exposed to Chemicals – React Quickly

Fires, tornadoes, hurricanes, floods, earthquakes, explosions, train wrecks, and other disasters change lives in an instant. The toxic fallout continues to affect us – and our family pets – long after the property damage caused by the disasters has been repaired.

Of course, the people who experience these disasters will seek and receive medical care. But what about their pets, especially dogs, who most likely accompanied their guardians throughout the ordeal?

For example, dogs exposed to forest fires and burning buildings inhale smoke, asbestos, and other toxins. Whenever an accident involves a manufacturing plant, tank truck, or train carrying toxic chemicals, dogs face the same risks as humans exposed to the spills or fumes. In the most dramatic example, when the World Trade Center collapsed on September 11, a cloud of smoke, dust, ash, pulverized concrete, asbestos, jet fuel, fiberglass, microscopic shards of broken glass, and toxic chemicals blanketed lower Manhattan. In the days and weeks that followed, thousands of resident dogs and hundreds of search and rescue dogs walked through the debris and breathed its vapors.

Less dramatic, but still harmful, is the exposure that dogs receive in neighborhoods treated by lawn care companies or insect control programs. Canine residents and passers-by absorb pesticides through their paw pads, noses, mouths, and lungs.

What can concerned dog lovers do to help keep yesterday’s toxic exposure from becoming tomorrow’s health problem? Plenty, say the experts.

Wash the dog

Of course, if you are aware your dog has been exposed to toxic smoke, dust, or chemicals, the first thing you want to do (after taking care of yourself and the rest of your human family) is to wash him as thoroughly as possible. Consult a poison control center or veterinarian regarding exposure to unfamiliar chemicals in the aftermath of a disaster such as a train derailment or overturned truck. But whether or not you are familiar with the chemicals that your dog was exposed to, wear rubber gloves when bathing him.

Don’t forget to wash your dog’s collar, leash, and any bedding that he may have come in contact with prior to the bath. Use a simple soap or shampoo – no insecticidal shampoos – and rinse especially well; poison control centers suggest that people rinse themselves for at least 15 minutes after skin exposure to chemicals. Don’t neglect the dog’s feet, which should be scrubbed well. Search and Rescue dogs working at the World Trade Center were bathed daily, and so should any dog exposed to smoke or dust.

Consult a holistic veterinarian

While many conditions respond well to home care, be ready to consult a veterinarian if your dog shows symptoms that might result from smoke inhalation, exposure to chemicals, or other hazards, including vomiting, coughing, weight loss, a loss of appetite, behavior changes, or limping.

Flushing the system

An adequate supply of clean, fresh water is always important for your dog’s health. But it’s absolutely critical for dogs who have to flush toxins from their bodies. “Because it hydrates the body and flushes toxins from the system, water should be given to any dog recovering from a disaster,” says Stephen R. Blake, DVM, of San Diego, California. Dr. Blake recommends that carbon-filtered or spring water be available to the dog at all times; tap water may contain impurities.

In fact, everything in the dog’s diet and environment should be free from toxins and pollutants, says Dr. Blake. “This is not the time to introduce any new chemicals or prescription drugs, including systemic treatments for flea and tick prevention or routine vaccinations. The body has to work hard to get rid of the toxins it has already absorbed; it doesn’t need any new ones.”

Pro-protein

What you feed your dog following toxic exposures can also make a difference in his speedy recovery. “The body needs easily assimilated protein, with all its amino acids and peptides, in order to repair and rebuild damaged tissue,” says Beverly Cappel, DVM, of Chestnut Ridge, New York. “This means feeding the highest quality protein, preferably organically raised, pasture-fed beef, lamb, chicken, and other meats.” She also recommends adding vitamin C, antioxidants, and food-source vitamins and minerals for optimum healing.

Dr. Cappel is an advocate of raw-food diets, and most of her clients already feed their dogs home-prepared diets that include raw meat. If a dog on such a diet has been exposured to toxins, she recommends that the owner strive to make sure the food the dog eats is as chemical-free as possible. If a dog eats commercial food, the owner should try to improve the quality of the food, but Dr. Cappel would not recommend starting the dog on a raw diet at that time. “If a person is feeding kibble, it should be the best quality kibble available. But you wouldn’t want to begin a raw diet, healthful as it may be, when the dog is stressed.”

Dr. Blake also recommends increasing the protein intake of dogs exposed to hazardous conditions by adding two ounces of fresh meat, eggs, cheese, or cottage cheese to each six ounces of whatever the dog is already eating. “If the dog is on a commercial food,” he says, “this is a good time to upgrade to a brand with a higher proportion of protein, which should be from whole meats rather than byproducts.”

Predigested protein improves canine health, for it is easily assimilated and quickly heals damaged tissue. The supplement Seacure, made from fermented deep-sea fish, is 85 percent protein. Most dogs love its strong fishy odor. The recommended human dose of six capsules twice a day can be adapted to any dog’s size, but for serious repair work, the body can utilize twice or four times the maintenance dose. After injuries heal, the maintenance dose continues to improve digestion and support detoxification.

Goat milk molecules are smaller than those of cow’s milk, making them easier to digest, and many nutritionists recommend raw goat milk or cheese, or predigested goat milk protein for optimum canine health. A supplement called Goatein, made from goat milk that is free of antibiotics or growth hormones, has been predigested through a lactic acid fermentation process to make it more bioavailable while eliminating its lactose (milk sugar). The result is a blend of digestive enzymes, probiotics (beneficial bacteria), prebiotics (substances that feed beneficial bacteria), amino acids, and peptides that repair damaged tissue, improve digestion, and boost immune function. Goatein powder mixes easily with food or water.

Fresh green tripe, unlike the bleached tripe sold for human consumption, is such a concentrated source of enzymes, peptides, and other nutrients that some call it a miracle cure. Severely ill, injured, and damaged dogs have recovered rapidly on green tripe, which can be added to food or fed in place of other foods. Its high odor awakens interest in all dogs, even the apathetic and depressed.

Green foods and herbs

Wheat, barley, oat, and other cereal grasses are known for their ability to bind with and remove toxins from the body. The same is true of green foods such as spirulina, chlorella, edible algae, and sea vegetables such as kelp.

Green foods are rich in chlorophyll, which has been used for centuries to clean and disinfect wounds, remove infection, and enhance healing. Taken internally, green foods provide vitamins, minerals, enzymes, and antioxidants that have a tonic effect on all of the body’s systems. Most health food stores sell a variety of green powders, frozen wheat grass juice, and in some cases, freshly squeezed wheat or barley grass juice.

Because green foods are highly concentrated, they should be taken in small quantities while the body adjusts. Large doses of green juices or powders cause nausea and vomiting. Adding small amounts of minced or pureed grasses, other green foods, and seaweeds to every meal is a sensible strategy for removing residues of chemicals a dog has ingested, inhaled, or absorbed.

Mucilaginous herbs have a soothing effect on inflamed mucous membranes and help repair damaged tissue. Dr. Cappel recommends feeding the dog mullein leaf following smoke inhalation or other lung damage. Other mucilaginous herbs, such as Iceland Moss, Irish moss, marshmallow, and slippery elm bark, help improve digestion. Teas, tinctures, and powdered herbs can be added to food or water.

Colostrum

Every mammal produces colostrum immediately after birth, and this “first milk” protects newborns from infection while their immune systems develop. Researchers document a wide spectrum of immunoglobulins, antibodies, and accessory immune factors in colostrum that stimulate the body’s defense against bacteria, viruses, and other pathogens. Colostrum strengthens the immune system, helps prevent allergies and autoimmune disorders, stimulates tissue repair, helps build lean muscle tissue, and regenerates nerve, skin, bone, and cartilage.

Dr. Blake recommends an organic bovine colostrum from New Zealand. “It’s excellent for keeping the intestinal tract as healthy as possible, so dogs can utilize all the nutrients in their food,” he says. “Because the immune system depends on the intestines, optimum intestinal health translates into optimum immunity. The growth factors in colostrum repair damaged tissue throughout the body, including the lungs, so colostrum helps dogs recover from smoke inhalation and other damage. Also, colostrum supports detoxification; it helps the body remove any toxins the dog ingested, inhaled, or absorbed through the skin.”

To improve the endurance of sled dogs and other working dogs, Dr. Blake recommends giving a half-teaspoon of powdered colostrum per 25 pounds of body weight per day. “That’s twice the maintenance dose,” he says, “and this same amount will help dogs recover from serious injury or exposure to toxic chemicals. If possible, mix the powder with water and give it on an empty stomach at least half an hour before the morning meal.” When the dog shows improvement, he reduces the dose to a quarter-teaspoon per 25 pounds of body weight per day.

“You can also use colostrum topically on wounds,” Dr. Blake says. “Mix a teaspoon of colostrum with enough water to make a thin paste and apply it to the wound. Dogs like the taste of colostrum, so try to distract the dog for five minutes to give it a chance to be absorbed into the skin. In my experience, wounds treated with colostrum heal at least 50 percent faster.”

Enzymes

Digestive enzymes given with food improve its assimilation, and enzymes given between meals work throughout the body to relieve inflammation and repair tissue. (For a detailed introduction to systemic oral enzyme therapy, see “Banking on Enzymes” WDJ January 2001.)

Systemic oral enzyme therapy has four main effects on the body: It is anti-inflammatory, fights fibrosis, cleanses the blood, and modulates the immune system. Most disease states involve two or more of these conditions, which explains how enzymes treat, repair, cure, and prevent most chronic and acute diseases.

Wobenzym tablets have a clear, sugar-free coating; Fido-Wobenzym is the red, sugar-coated product with a canine label that recommends 1 to 3 tablets per day as a maintenance dose for dogs. Anyone treating a dog for trauma, smoke inhalation, asbestos exposure, or other injuries will want to use substantially larger doses for a week or more. Regular Wobenzym, which is sugar-free, is sold in larger jars than Fido-Wobenzym, making it more economical.

Aromatherapy

Most Americans associate aromatherapy with scented candles, but in Europe, aromatherapy is a highly regarded branch of medicine that utilizes essential oils. Essential oils are the highly concentrated “life blood” of plants, collected through steam distillation or carbon dioxide extraction. Therapeutic essential oils are produced in small batches at gentle temperatures from organically grown or wildcrafted plants.

“Therapeutic-quality essential oils maintain the biological activity of the plants,” explains Dr. Blake, “and certain plants have unique healing properties. In my experience, frankincense essential oil is most helpful for repairing the immune system and supporting detoxification. It has antibacterial, antiviral, antifungal, and antitumor effects. Applying frankincense essential oil to a dog’s paw pads causes the oil to be absorbed through the skin while the dog inhales its vapors, which most dogs enjoy. Also, the paw pads contain many acupuncture points, which are activated when you apply essential oils.”

Blake recommends placing one drop of full-strength frankincense essential oil on each pad, a total of five drops on each front foot and four on each back foot, once per day, massaging gently.

“Be sure to use a therapeutic-quality essential oil,” he cautions. “This treatment can be dangerous if done with inexpensive synthetic or inferior oils. Continue daily treatment until the dog shows improvement. Once the dog has recovered, when his eyes are bright and clear and his energy level is strong, use it every other day, then whenever his energy seems to decline or when the dog is working or under stress.”

For search and rescue dogs, tracking dogs, and field dogs that depend on their sense of smell, Dr. Blake suggests waiting until the day’s work is over and then treating the paws with frankincense.

Flower essence remedies

The final phase of Dr. Blake’s treatment plan for dogs affected by disaster utilizes Bach flower remedies. “Flower remedies affect dogs on an emotional level,” he says. “They really help during this time of transition, when the traumatic event is over but its memory is still strong.”

To use flower essences, mix two drops of each essence in a one-ounce dropper bottle, preferably one with a glass rather than plastic dropper. Fill it three-quarters full with spring water and a quarter with brandy or vodka, which acts as a preservative so that the mixture keeps for a week or two. Alternatively, omit the alcohol and prepare the formula every day or two.

Dr. Blake’s formula for dogs recovering from disaster combines two drops each of walnut, crabapple, star of Bethlehem, wild oat, and wild rose flower essences.

During and immediately after a disaster, apply this formula frequently, such as every hour. When the dog is home again and life returns to normal, give it twice or three times per day until the dog recovers emotionally. Then use only as needed.

Flower essences can be given by mouth, two to three drops at a time, added to drinking water, applied to the paw pads or bare skin (inner ear flaps, abdomen, or underarm), or sprayed in the air around the dog.

“Most dogs will bounce back within a week or two on this formula,” says Dr. Blake, “but some take longer. If you don’t see improvement after a month of daily use, consult with a flower essence expert for a formula for your dog’s specific needs.”

We hope that you and your dog never come into contact with dangerous toxins. But whether you (or someone you know) has a dog that suffers an unexpected exposure, or if you and your dog are among the heroes who deliberately put themselves in harm’s way in order to attempt to save others in a disaster zone, keep this information on hand. It just may prevent serious illness days or weeks after the trauma.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Could Your Dog Be Breathing In Toxins in Your Home?”

Click here to view “Drinking the Purest Water Possible is Important to Your Dog’s Health”

Click here to view “How to Detoxify Your Canine Naturally”

-by CJ Puotinen

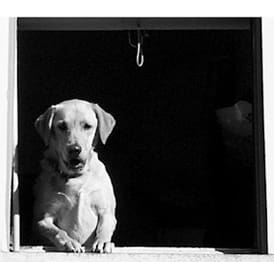

CJ Puotinen is the author of The Encyclopedia of Natural Pet Care, Natural Remedies for Dogs and Cats, and several books about human health including Natural Relief from Aches and Pains, published last summer. She and her husband live in New York with Samantha, a nine-year-old black Labrador Retriever, and two cats.

Training and Socializing Dog-Aggressive Dogs

Editor’s Note: Twenty years ago, people freely used the term “aggressive dog” to describe what, today, we would call a “dog with aggressive behaviors.” The problem with the term “aggressive dog” is that very few dogs are aggressive all the time – and if they are, they are unlikely to be in anyone’s home. Most dogs who display aggression in some situations are loving and loved dogs in other circumstances; calling them “aggressive dogs” overlooks the fact that they are terrific dogs most of the time. Throughout this article, we may use the older, more familiar term, and we will add the modern term that more accurately describes a dog who sometimes displays aggressive behaviors.

Going for a walk with your dog may be one of your favorite ways to exercise and relax, but your pleasant outing can quickly turn into a stressful one if your dog reacts badly to other dogs and you happen to encounter one running loose. If the other dog is threatening or if you have an aggressive dog (a dog with aggressive behaviors), a dog fight could ensue, and the situation can become downright dangerous.

Like most owners of antisocial dogs, Thea McCue of Austin, Texas, is well aware of how quickly an outdoor activity with her dog can stop being fun. Wurley, her 14-month-old Lab mix, is a happy, energetic dog who loves to swim and go running on the hike-bike trails around their home. But when he’s on-leash, he barks at other dogs, growls, and even lunges.

Because Wurley is 22 inches tall and weighs 60 pounds, he can be hard to handle, says McCue. “When he pounced on one little 10-pound puppy, it was embarrassing for me and scary for the puppy and the puppy’s owner!” Indeed, introducing a puppy to a dog-aggressive dog may be one of the scariest experiences a dog owner can have!

Why Are Some Dogs So Hostile Toward Other Dogs?

If, like Wurley, your dog is reactive to other dogs, you are far from alone. Tense encounters between dogs are not unusual, as dogs who don’t get along with other dogs now seem close to outnumbering those who do. In fact, dog-on-dog aggression is one of the most common behavior problems that owners, breeders, trainers, shelter staff, and rescue volunteers must deal with. So what to do with an aggressive dog (a dog who is aggressive toward other dogs)?

The major reason why dogs become aggressive toward other dogs, says Dr. Ian Dunbar, founder of the Association of Professional Dog Trainers (APDT), is that during their puppyhood, dogs are often deprived of adequate socialization with other good-natured dogs. As a result, many pups grow up with poor social skills, unable to “read” other dogs and exchange subtle communication signals with them.

Regular contact with playmates is necessary for dogs to develop social confidence. The popularity of puppy classes can be traced to Dunbar’s pioneering efforts to provide puppies with a way to experience this vital contact with one another. If puppies miss out on these positive socialization experiences, they are more at risk of developing fear-based provocative behaviors. Because dogs who show aggressive tendencies tend to be kept more isolated than their socially savvy counterparts, their anti-social behavior tends to intensify as they get older.

How to Train an Aggressive Dog

Fortunately, there is a way out of this dilemma. If your dog attacks other dogs, or just really doesn’t like other dogs, the good news is that new dog training techniques are being developed that can help you change your dog’s association and aggressive response to other dogs. Like McCue, who opted to take Wurley to “Growl” classes, you may find these training remedies can improve your dog’s manners so that you can feel comfortable handling him in public again.

Although the techniques themselves may be new, Jean Donaldson, author of Culture Clash and founder/principal instructor for the Academy for Dog Trainers, says that they are solidly grounded in behavioral science theory and the “laws of learning.” Though different trainers design their own classes differently, in general, “Growl” classes are geared to teach dogs to associate other dogs with positive things, and to teach dogs that good behavior in the presence of other dogs will be rewarded.

The first method commonly used in dog aggression training classes involves simple classical conditioning—the dog learns that the presence of another dog predicts a food treat, much as Pavlov’s dogs learned to associate the sound of a bell with dinner coming.

Operant conditioning is also used to teach the dog that his own actions can earn positive reinforcement in the form of treats, praise, and play. Both types of conditioning attempt to change the underlying emotional that leads to aggression in dogs, rather than just suppressing the outward symptoms with punishment.

Outdated Ways of Socializing Dogs

This approach is a departure from the past; only a few years ago, most trainers recommended “correcting” (punishing) lunging and barking with a swift, hard leash “pop” (yank). Although this forceful method can interrupt an aggressive outburst, it seldom produces any lasting improvement—and it does nothing to change the way the dog will “feel” or react the next time he sees another dog.

In fact, this sort of punishment often exacerbates the problem by sending the wrong message to the dog; he learns that proximity to other dogs brings about punishment from the owner! This can stress him more and cause him to behave even more aggressively. Teaching him to anticipate scolding whenever another dog is nearby is not how to calm an aggressive dog (a dog who displays aggression at other dogs).

Punishment results in additional negative side effects. A dog who has been punished, just like a person who has been physically or verbally rebuked, usually experiences physiological stress reactions that make it harder for him to calm down. Also, when a dog growls at other dogs or shows signs of unease and is punished, the dog may simply learn to suppress his growling and visual signals of discomfort; the result can be a dog who suddenly strikes out with no warning.

These are some of the reasons that behavior professionals like Dunbar and Donaldson now believe that it is absolutely necessary to eliminate all punishment and reprimands when dealing with a dog who is aggressive to other dogs

Training an Aggressive Dog: 4 Components of an Effective Program

In the most effective aggression-retraining programs, unpleasant or punishing training methods (“aversives”) are strictly avoided. Among other things, trainers who work with aggressive dogs (dogs with challenging aggressive behaviors) will often use a “Say Please” program. The basic premise is that the dog responds to an obedience cue in order to earn freedoms and privileges. These include meals, treats, toys, play, games, walks, and even attention and petting. The goal is to teach the dog to offer polite behaviors in order to obtain good things in his life.

Meanwhile, the first step in specifically dealing with the dog’s aggression might merely be rewarding the dog for any behavior that does not involve fighting or aggression. His behavior is then modified through a planned program of:

- shaping (reinforcing each small action the dog makes toward the desired goal);

- desensitization (presenting other dogs at sufficient distance so that an aggressive reaction is not elicited, then gradually decreasing the distance);

- counter-conditioning (pairing the presence of other dogs with pleasant things);

- training the dog to offer behaviors on cue that are incompatible with aggression.

An example of the latter would be short-circuiting a dog from lunging by having him instead do an incompatible behavior (such as a “sit-stay”) while watching the handler. Eventually, the dog can even be trained to offer this behavior automatically upon sighting another dog. (“If I turn and look at my handler when I see a dog, I’ll get a sardine—yum!”)

Another cornerstone technique, originally developed by behavior counselor William Campbell, is commonly known as the “Jolly Routine.” An owner is taught to use her own mood to influence her dog’s mood—when your dog is tense, instead of scolding, laugh and giggle him out of it.

This same technique can work on fearful dogs. Make a list of items, words, and expressions that hold happy meanings for your dog and use them to help elicit mood changes. “The best ‘double punch’ is to jolly, and then deliver food treats,” says Donaldson. “The bonus to this technique is that it also stops the owner from delivering that tense, warning tone: ‘Be ni-ice!’ ”

How to Socialize an Aggressive Dog

The “Open Bar” is one exercise that might be considered an offshoot of the jolly routine, and it, too, makes use of classical conditioning. Here’s how it works:

For a set period of time (weeks or months, as needed), whenever another dog appears, like clockwork you offer your own dog sweet baby talk or cheery “jolly talk” and a special favorite food never given at any other time. The “bar opening” is contingent only on the presence of other dogs; therefore the bar opens no matter how appropriately or inappropriately your own dog behaves. Likewise, the “bar” closes the moment the other dogs leave – you stop the happy talk and stop feeding the treats.

Skeptics may ask whether giving treats to a dog whose behavior is still far from angelic does not actually reward undesirable behavior. But behavior professionals explain that the classical conditioning effect–creating a strong positive association with other dogs–is so powerful that it overrides any possible reinforcement of undesirable behavior that may initially occur. The unwanted behavior soon fades in intensity.

Another advantage of the Open Bar technique is that it can be incorporated into training protocols that are easy to set up, such as “street passes.” Street passes are also a means of using distance and repetition to desensitize your dog to other dogs. The final goal is for your dog to be able to walk by a new dog and do well on the first pass.

All you need to set up a training session using street passes is the help of a buddy and her dog. Position yourself about 50 yards from a place where you can hold your dog on leash, or tie him securely to a lamp post or tree. Ideally, this should be on a street, about 50 yards from a corner, so your friend can pass through an area of your dog’s vision and then disappear.

Your friend and her dog should wait out of sight until you are in position and ready with your treats. At that point she should appear with her dog, strolling across an area within your dog’s sight. As soon as she and her dog appear, open the bar and start sweet-talking your dog as you give him treats. The moment that your buddy and her dog disappear from sight, the bar closes and you stop the treats and attention.

If your dog “goes off” (goes over threshold) when your friend appears with her dog, you are too close. Increase the distance and try again, until your dog can stay reasonably calm and take treats when your friend appears with her dog. Counter-conditioning works best if you can keep your dog below threshold, and very gradually decrease distance as you are successful.

Similar sessions can be set up in quiet parks or out-of-the-way places:

With your dog on leash, stand several feet off a path (or farther, if necessary to keep him below threshold), as your friend walks by with her dog, also on leash. Both dogs should have an appetite (don’t work on this right after your dog has been fed!) and you and your friend need to have really yummy treats in hand to help keep your dogs’ attention on you and to reward them for good behavior.

Have your friend walk by with her dog. If your dog is able to maintain a sit without lunging or barking, repeat multiple times. (If your dog is over threshold, increase the distance between you and your friend and try again.) As training progresses, you will gradually reduce the distance necessary for your dog to react calmly with what Donaldson calls an “Oh, you again” response when the familiar dog passes by. Repeat the same process as new dogs are introduced into the equation.

Growl Classes

Naturally, the more dogs that your dog can interact with, the better chance he will improve his behavior. If the dog has bite inhibition (when he does bite another dog, the bites are not hard enough to break the skin of his victim), Donaldson believes the ideal solution is a play group of “bulletproof dogs” who are friendly, confident, and experienced enough to interact well with him. Unfortunately, this kind of play group is not easy for most owners to replicate on an as-needed basis.

Donaldson says the second-best thing is a well-run “growly dog class” just for aggressive dogs (dogs with aggressive behaviors). One way these classes differ from regular training classes is that everyone in them is in the same boat, and therefore willing to work together to overcome their dogs’ behavior challenges.

One of the most comprehensive programs is offered by the Marin Humane Society in Novato, California. Training director Trish King says MHS’s “Difficult Dog” class size is limited to eight dogs and progress proceeds in baby steps.

“The first class is very controlled,” she describes. “We’ve prepared a small fenced area (using show ring gating) for each dog and the first couple of weeks we throw towels over the fences to prevent the dogs from making eye contact. By week three, the coverings have been removed. By the fourth week we have a few dogs in muzzles wandering around each other. The goal is to have the dogs remain under control when another dog runs up to them!”

King says that proper equipment is part of the formula for success. Dogs are acclimated to wearing Gentle Leaders (head halters) for on-leash work and muzzles for off-leash work. Since muzzles can interfere with the dogs’ ability to pant, care must be taken not to let dogs become overheated while using them. No pinch collars or choke chains are allowed.

“We’ve found that most people have already tried to use corrective collars, and they haven’t worked,” says King, “probably because of the lack of timing on the owners’ part, as well as the fact that these collars can set the dog up for identifying other dogs as a threat; they see an oncoming dog, while they feel the pain of the collar jerk, and they hear their owner yelling at them.”

Changing this common scenario begins with teaching owners to keep the leash short but loose. Instead of punishing corrections, MHS instructors use a variety of exercises to train dogs to avoid conflicts.

“We teach dogs to follow their owners, not to pull on leash, to watch the owner, sit, down, stay, and so on,” says King. “We also teach the owners how to massage their dogs, and how to stay calm and in control at all times. More than anything else, the class is to help owners control and manage their dogs.”

Changing the Dog Handler’s Behavior to Manage Aggression

Across the continent in Toronto, Canada, Cheryl Smith, who developed some of the concepts used at MHS, also believes that working with owners and dogs as a team is one of the most important components of her Growl Classes. One of the first things that Smith teaches owners is how to take a deep breath and relax about everything. Owners who remain calm are better able to pay attention to their dog’s body language and to observe what triggers aggression.

Without special coaching, owners are likely to do exactly the opposite, thus making the problems worse.

For example, if you anticipate or respond to your dog’s aggressive behavior by tightening up on his leash, you will reinforce his perception that he should be leery of other dogs. If you get upset when he lunges and barks, your emotions will fuel his tension and aggression. If you continue to punish and reprimand your dog after he has started to settle down, you will only confuse him and make him more stressed, because punishment that comes more than a couple of seconds after a behavior is too late – your dog will think he is being punished for being quiet!

In contrast, the right approach utilizes prevention and early intervention. The dog must be prevented from repeating the problem behavior because every time that he does so successfully it will become more entrenched! Interventions may include moving to break eye contact, using a body block to prevent physical contact or to redirect forward movement, walking away quickly with the dog, giving a cue such as “Gentle” (open the mouth and relax the jaw) or “Off” (back away), and offering treats to defuse or interrupt tension interactions.

Dogs Learn at Their Own Pace

Of course, there will be some dogs who don’t respond adequately to any dog-aggression training program. These may require a referral to a certified veterinary behaviorist who can prescribe appropriate behavior medications as part of the treatment arsenal. If you have an aggressive dog (a dog with aggressive behaviors), you have a responsibility to ensure his safety and that of others by taking appropriate measures, including the use of a muzzle when indicated.

But no matter how serious your dog’s problem may be, Jean Donaldson advises keeping it in perspective:

“In any discussion of aggression, it bears remembering that the bar we hold up for dogs is one we would consider ridiculous for any other animal, including ourselves. We want no species-normal aggressive behavior directed at any other human or canine at any time, of even the most ritualized sort, over the entire life of the animal? It’s like me saying to you, ‘Hey, get yourself a therapist who will fix you so that for the rest of your life, you never once lose your temper, say something you later regret to a loved one, swear at another driver in traffic, or yell at anyone, including your dog.’ It’s a tall order!”

In other words, keep your expectations realistic. Then, if you stick with the program, the odds are you will end up pleased with the results, like Thea McCue. After completing their Growl Class course with trainer Susan Smith, owner of Raising Canine in Austin, she and Wurley are once more able to hit the hike and bike trails together again. Describing Wurley’s progress thus far, McCue says, “he warms up to other dogs much faster and rarely reacts to dogs while we’re running.” Although there remains room for improvement, Wurley’s days of pouncing on puppies are over!

Download the Full November 2001 Issue

Join Whole Dog Journal

Already a member?

Click Here to Sign In | Forgot your password? | Activate Web AccessWorking With Obsessive/Compulsive Dogs

The dainty, 18-month-old Cavalier King Charles Spaniel appeared perfectly normal and happy when she and her owner greeted me at the door, but I knew better. Her owner had already advised me over the phone that Mindy was a compulsive “fly-snapper,” and that the stereotypic behavior had intensified in recent weeks, to the point where it was making life miserable for both Mindy and her owner.

Indeed, it was only a matter of minutes before I saw Mindy’s expression change to one of worry, then distress and anxiety, as her eyes began to dart back and forth.

Shortly thereafter she started snapping at the air, for all the world as if she were trying to catch a bevy of irritating flies that our human eyes could not see. Her efforts grew more frantic and her demeanor more anxious, and included stereotypic tail-chasing, until she finally ran from the living room into the safety of her crate in the darkened pantry.

Fly-snapping is one of a number of repetitive behavior syndromes from which dogs may suffer. Other such behaviors include spinning, tail-chasing, freezing in a particular position or location, self-mutilation (biting or licking), and flank-sucking. Some behaviorists also include pica – the ingestion of inedible objects such as rocks, sticks, socks, and who knows what else, in the compulsion syndrome family.

While these behaviors are very similar to the condition known as obsessive-compulsive disorder in humans, many behaviorists believe that the term canine compulsive disorder is more appropriate to describe the behaviors in dogs.

In human psychology, obsessions are persistent, intrusive thoughts that cause extreme anxiety and that the patient tries to suppress or ignore. Compulsions are repetitive behaviors that the patient performs in order to prevent or reduce the anxiety. Behaviorists argue that because we don’t know whether dogs actually have obsessive thoughts (although Border Collie owners could argue this!), we should omit the word “obsessive” and use the term “canine compulsive disorder” (CCD) to describe the syndrome in dogs.

Clinical signs, causes, and treatment

Very little research has been done into CCD – much of what we know about the syndrome is based on anecdotal evidence, and even that is relatively rare. The primary cause is believed to be a situation of conflict or frustration to which the dog must try to adapt. The disorder often begins as a normal, adaptive response to the conflict or frustration. Eventually the response becomes removed from the original stimulus and occurs whenever the dog’s stress or arousal level exceeds a critical threshold.

Strong evidence exists that genetics play a role in at least some compulsive behaviors. There is a higher-than-average incidence of tail-chasing in Bull Terriers and German Shepherds, fly-snapping in Cavalier King Charles Spaniels, and excessive licking (acral lick dermatitis) to the point of causing a lesion (lick granuloma) in many large breeds, including the Doberman Pinscher, Golden Retriever, Labrador Retriever, and German Shepherd. Flank-sucking is an often-seen compulsive behavior in Dobermans as well.

Trainers and behaviorists suspect that CCD is probably underdiagnosed, as very few veterinary schools give their students thorough training in animal behavior, and many owners don’t recognize or don’t report compulsive behaviors. A behavior falls into the compulsive category when it becomes a stereotypy – a repetitive and unvarying pattern of behavior that serves no obvious purpose in the context in which it is performed. Compulsive behaviors often evoke a response from the owner, and thus may be unwittingly reinforced as a result.

Early intervention helps

That was certainly the case with Dodger, an eight-month-old Golden Retriever in Carmel, California, whose owner was battling with the challenge of pica. Perhaps because they are bred for a genetic predisposition to hold things in their mouths (i.e. retrieve), Goldens and Labrador Retrievers seem to suffer from a higher incidence of pica than many other breeds of dogs. Dodger was allowed outside only under strict supervision, as he would compulsively eat sticks and rocks, and had already had one emergency life-saving surgery to unblock his digestive tract.

Now Dodger was beginning to chase his tail. Since the pup already was engaging in one compulsive behavior, his owner was rightfully concerned that tail-chasing was another manifestation of CCD. Physical restraint – chaining, kenneling, or other close confinement – is one of the situations of conflict or frustration that can contribute to compulsive behavior (see “Conflict and Frustration,” next page). Frustration refers to a situation in which an animal is motivated to perform a behavior but is prevented from doing so.

The obvious solution to Dodger’s tail-chasing was to give him more freedom and exercise in his fenced yard, thereby reducing the confinement frustration while also, hopefully, tiring Dodger out to the point that he didn’t have enough energy left to chase his tail (from the “a tired dog is a well-behaved dog” school of behavior modification). Because of his pica problem, this wasn’t an option for Dodger.

We hypothesized that owner attention was also feeding the tail-chasing, so we established a modification protocol that consisted of the owners immediately leaving the room as soon as the behavior started, and making an effort to pay more attention to Dodger when he wasn’t chasing his tail.

Dodger was fortunate. His owners, despite the considerable responsibility of a new-born baby, adhered faithfully to the modification program while also increasing the length and frequency of Dodger’s supervised walks. Inside of a month, the tail-chasing had subsided.

Several factors contributed to the unusually quick and complete success in Dodger’s case. Dodger was young, and his owner noticed and reported the behavior very early in its development. Early implementation of a behavior modification program provides for a much more positive prognosis than does a situation where the dog has had years to practice the stereotypic behavior. Dodger’s tail-chasing had a clear attention-seeking component, so removing the reward of the owners’ attention for the behavior was an effective approach. Finally, both owners were committed to the training and were consistent about applying the recommended treatment, which was instrumental to success.

Don’t use drug therapy alone

Mindy was not as fortunate as Dodger. Her fly-snapping behavior had started when she was about six months old. Because it was relatively mild at first, her owner didn’t seek treatment. When she did report it to her veterinarian, she was told that it was a form of mild seizures and that the only treatment was a lifetime of drug therapy – Phenobarbital – which has serious side effects and is highly likely to shorten the dog’s life expectancy.

Mindy’s owner was understandably and rightfully reluctant to resort to such an approach, and believing there was no alternative, chose to do nothing. By the time I saw her a year later, the behavior was well-established, very strong, and extremely difficult to modify solely through a behavioral approach.

At one time, seizures were believed to play a role in fly-snapping behavior, but that is no longer the case. Behavioral scientists also hypothesized at one time that an endorphin release accompanied the performance of compulsive behaviors, which was believed to reinforce the behavior, but recent research has also determined this to be untrue.

While the cause of CCD is still not well understood, there is some evidence of serotonin involvement, and drugs that inhibit serotonin re-uptake have been used effectively to treat dogs with CCD.

Treatment program

Treatment consists of both environmental and behavioral modification, and, often, pharmacological intervention. Here are 10 steps to a successful treatment program:

1. Intervene as early as possible.

2. Have your veterinarian conduct a complete physical examination and evaluation to identify and eliminate any medical conditions that may be contributing to or causing the behavior.

3. Identify and, if possible, remove the cause(s) of the dog’s stress, conflict, or frustration.

4. Avoid rewarding the compulsive behavior. Remember, it can be rewarding for the dog simply to have his owner pay attention to him.

5. Eliminate any punishment as a response to the compulsive behavior.

6. Provide sufficient exercise on a regular schedule.

7. Consult with an alternative practitioner to apply alternative modalities such as massage techniques, herbal therapies, acupressure, and acupuncture, to help relieve the dog’s stress.