Download the Full April 2003 Issue

New Dog Do’s and Don’ts

By Nancy Kerns

When I hear that someone I know is getting a dog, I experience mixed feelings. I’m hopeful it will work out, and fearful that it won’t. In the six years that I’ve edited WDJ and paid close attention to such things, I’ve seen a score of my friends, neighbors, and acquaintances bring home a new dog or puppy. And, sadly, about half of those new dog/people relationships didn’t work out – a euphemism which means here, they had to find another home for the dog. When this happens, it’s not ethical, it’s not cool, it’s a tragedy for all concerned – and in my view, it all can be prevented.

Often, new-dog ventures fail most frequently when people don’t take enough time – time to research what sort of dog is really best for them, time to prepare for the dog’s arrival, and time to spend with the dog. In fact, the first thing I ask when I hear someone is thinking about getting a dog is, “How much time do you have?”

The following is a brief distillation of everything I’ve learned about what makes new dog/human relationships successfully sail off into the sunset, and what causes the ship to sink within days, weeks, or months.

Pre-planning for the dog

I never fail to be amazed at the number of people I hear about who decide to get a dog, go to the shelter, and come home with one – all in the same weekend. At least half a dozen of the sad dog/family relationship failures I’ve seen in recent years have been due to a hasty adoption; the people just didn’t take enough time to evaluate the dog or their own abilities to deal with it.

Give yourself at least a month to do some long, hard thinking about what sort of dog you want. Visualize the whole package: your ideal dog’s age, size, coat, energy level, attention span, ability to give and receive affection, sociability, portability, and health status. Plan to visit shelters a few times a week for a month or so without bringing a dog home. Keep the vision of your ideal dog in mind as you visit, even if you begin to discover that there are a few aspects of your “perfect dog” vision that you are willing to be flexible about.

But don’t depart from your vision too much! Little things can grow into big issues over time, compounding with each new problem. For example, say you have gorgeous hardwood floors in your home, and your vision of your ideal canine companion is a clean, short-haired dog. But then you fall in love with a shaggy Australian Shepherd cross. Over time, you learn that in order to keep your floors as pristine as you like them, you have to vacuum or sweep every day – or keep the dog out. And as the dog spends less time with you in the living room, he becomes more anxious and more unruly. The ship starts sinking . . . and, for the dog, the impending disaster will be titanic.

I know how hard it will be to walk away from close candidates. But I also know with a certainty that there is a perfect candidate for your “best dog ever” in a shelter near you. Don’t settle for a dog who doesn’t gladden your heart in every way, and you won’t find yourself returning an older, sadder, and less-adoptable dog to the shelter down the road.

For more in-depth information on choosing the best dog, see “How to Pick a Winner,” July 2001, on evaluating shelter dogs for a safe, friendly, adaptable temperament; “Second-Hand Friends,” April 1999, on the importance of selection and early training for shelter dogs; and “When Only a Purebred Will Do,” May 2002, on how to find your ideal breed, and how to find a responsible breeder.

Infrastructure items

As you look for your new best friend, start getting your house in order. Purchase all the stuff you are going to need: a leash, toys, chews, treats, a bed, shampoo. (See “The Dog Owner’s Hope Chest,” WDJ February 2002, for more “must-have” dog care items.) Think about containment. Do you need baby gates, a crate, tethers, a pen for the backyard, or major fencing improvements? If your home is completely prepared and able to safely and easily contain your dog, it will seem a lot easier having him live with you.

As you prepare on the physical plane, consider how your new dog’s needs are going to change your spiritual life. I’m only sort of joking; can you feel blessed and happy if you’ve been sleepless due to a whimpering puppy? Are you committed to taking walks every day, no matter how much snow has fallen, or how stifling the heat becomes? These are the kind of things you have to be ready to meet with your chin up.

And while we’re talking about full emotional preparation, how is everyone else in your household feeling about your new dog project? Does anyone in your home have reservations about the new dog’s impact on their life-styles? If so, work out solutions before the dog shows up. A tense emotional environment can definitely delay or prevent a dog’s emotional settling-in.

For more ideas on how to get the house ready, see “A Gated Community,” July 2002 and “In the Dog House,” September 1998.

A welcome home

Many people imagine that the day they bring home their dream dog will be the best day they’ll ever spend together, full of joyous discoveries and loving moments. That’s how it works in the movies!

The reality should be more like a movie shoot – scripted, structured, with all the scenery in place, and all cast members aware of their parts and on their marks.

Your new dog – the star of the show – should feel he has perfect freedom and leisure to explore his new home. In actuality, you should have constructed the set so that he is unable to go anywhere he’s not supposed to be (such as your allergic daughter’s room, or the unfenced front yard).

Also, while feeling that he is not being forced to interact with anyone just yet, he should nevertheless be under the constant supervision of an attentive family member. Don’t assume any level of housetraining, but treat him as you would a young puppy. Take him outside every hour or so, reward him richly when he relieves himself in an appropriate place, and don’t give him any opportunity to make a mistake in the meantime. When he’s in the house, keep him in your direct view, tied “umbilical cord” fashion to your waist by a leash, or in a crate until you see that he fully understands housetraining.

For descriptions of housetraining strategies, see “Getting Off to the Best Start,” January 1999 and “Minding Your Pees and Cues,” December 2001.

Finally, while your impulse will probably be to cancel everything else in your appointment book to spend every possible minute getting to know the new dog or puppy, you should follow your household’s usual routines. So many people pick up their new dog on Friday afternoon, spend the entire first weekend in a more or less constant, loving embrace with the dog, abandon him in favor of work and school on Monday –and then freak out Monday night when they come home and see all the damage caused over the last 10 frightening hours by the confused and anxious dog.

Instead, start habituating the dog to spending time alone in the house on the very first day he lives there. You accomplish this in tiny increments. Leave him alone in the kitchen with a food-stuffed Kong toy for 10 minutes while you watch TV in the next room. If he handles that okay, take him outside for an opportunity to relieve himself, and then leave him in his crate for an hour while you soak in the bathtub upstairs. Your goal is to build his confidence, in just a couple of days, that no matter how long you’re gone, you’ll return and he’ll be okay.

See “Learning to Be Alone,” July 2001, for critical information on how (and why) to prevent your dog from developing separation anxiety.

Train, train, train

My final recommendation would be to enroll in a positive dog or puppy training class as soon as possible. The more training and socialization your dog has, the better for everyone who meets him. Classes give you both an opportunity to learn to observe and communicate with each other. Practicing between classes, during walks and at home, is good mental and physical exercise for both of you. And the more time you spend together in a mutually enjoyable, interesting activity, the better it is for building permanent bonds between you.

The Right Herbal Remedy For Your Dog

With new herbal products popping up like weeds on store shelves everywhere, it can be difficult to decide which ones are right for you and your dog. There are herbal remedies for immune system support, cardiovascular health, worms, fleas, nursing bitches, and dogs with urinary problems. Herbal products with cute and clever labels (most of which tell us nothing) have appeared on the shelves of health food stores, pet supply stores, even in mainstream supermarkets.

Some of these products are very effective while others are nothing more than gimmicks that serve only to take your money. And as if things aren’t confusing enough, federal regulators currently prohibit even the best manufacturers from making reasonable and valid label claims about the intended uses of their products. I hope this will change one day.

Until then, the job of learning which products are right for you and your animal companions is entirely up to you. Fortunately, a wealth of herbal information waits in every bookstore, and whether you know it or not, many of the most effective herbal remedies are already at your fingertips. In fact, they may be as close as the kitchen cabinet.

Which Herbs are Safe for Dogs?

Even the most experienced herbalists (myself included) sometimes fail to look in the kitchen when the need for an herbal remedy arises. “Kitchen herbs” seem lackluster—they are not as trendy or sexy as plant medicines with long, exotic-sounding names. Perhaps they just don’t appeal to the mental image of a wise old medicine woman carefully harvesting odd-looking berries from a dark, primeval forest. Nevertheless, some of the most useful and safest herbs for animals are stored in our kitchens. Here are a few of my favorites.

Dill is Good for Dogs’ Digestion

Dill is very good for relieving nausea and flatulence in dogs, especially when such maladies are secondary to a sudden change in diet, such as when your puppy swipes a tamale from your foolishly unattended dinner plate. The effectiveness of dill in this capacity is largely attributable to the plant’s numerous volatile oil constituents, which exhibit an anti-foaming action in the stomach, much like over-the-counter anti-gas remedies. The highest concentrations of these oils are held within the seeds of the plant, but the dried leaves and stems (the stuff you are likely to have in your kitchen) can be used, too.

If your dog is belching something suspiciously reminiscent of what was supposed to be your dinner, and the problem appears to be getting worse, make a tea by steeping one tablespoon of dill seed in eight ounces of very hot water. After the tea has cooled, strain it and try direct-feeding two ounces of the liquid to your companion. If your dog doesn’t like the flavor, try adding the tea to his drinking water. Or if need be, disguise it as “yummy people food” by mixing it with some clear, low sodium broth instead of water. A sprinkling of ground dill seed on his food may also bring about symptomatic relief, but the liquid option tends to be more effective.

Fennel and Fennel Seed are Good for Gastric Distress in Dogs

Fennel seed represents another option for relief of gastric discomfort. A cooled tea works very well for this purpose; one teaspoon of the dried seeds in eight ounces of boiling water, steeped until cool. The tea can be fed at a rate of two to four tablespoons for each 20 pounds of your dog’s body weight, or it can be added to his drinking water, as generously as he will tolerate. A glycerin tincture also works very well, and allows the convenience of a smaller dosage for finicky animals; 10-20 drops (or more precisely, up to 0.75 ml) per 20 pounds of the animal’s weight, as needed.

Fennel is high in vitamins C and A, calcium, iron, potassium, and varying amounts of linoleic acid. It is an especially good nutritional adjunct for dogs whose chronic indigestion cannot be attributed to a specific disease entity. Fennel also helps increase appetite, and freshens the breath—thanks to its antibacterial activity in the mouth—and by minimizing belching. Fennel also has estrogen-like properties, which may explain why the herb has been used for centuries to increase milk production in nursing mothers. Some herbalists find that fennel helps alleviate urinary incontinence in spayed dogs by acting on hormone imbalances that contribute to the problem.

Rosemary is Good for Dogs’ Hearts

Rosemary is an extremely useful herb. At the top of its medicinal attributes are nervine, antidepressant, antispasmodic, and carminative properties. These combine to make rosemary an excellent remedy for flatulent dyspepsia and other digestive problems that are secondary to general nervousness, excitability, or irritability.

The rosmarinic acid contained in the plant is also believed to have painkilling properties, especially in situations where pinched nerves are suspected. In such instances 0.5 ml (about 1/8 tsp.) of the tincture can be given orally, as a starting dose, for each 20 pounds of a dog’s body weight, up to three times daily.

Rosemary is also useful as general cardiovascular tonic, moderating and improving heart function and strengthening capillary structure. A cooled rosemary tea (two tablespoons to a quart of water) serves as a very good, pleasant-smelling rinse for itchy skin, and because of the ursolic acid, rosemarinic acid, carnisol, and other antibacterial constituents it contains, the rinse can be very effective for relieving the symptoms of various bacterial infections of the skin.

For itchy skin and fleas, cooled rosemary tea can be poured into the coat as a soothing, healing, flea-repellent rinse. Rosemary also has excellent anti-microbial properties inside or on your companion’s body. Scientific studies have shown that it is active against various types of fungi, as well as numerous Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria. This makes it useful in antibacterial skin and eye rinses, minor cuts and burns, and for fighting infections of the mouth, throat, and the urinary and digestive tracts.

Rosemary essential oil is thought to stimulate the nervous system, and may have a worsening effect upon epileptic seizures. Although rosemary in its natural form contains only a small amount of essential oil, it is probably best to avoid this herb altogether if your companion is epileptic. If applied in concentrated form, the volatile oils in rosemary may cross placental barriers and can effect uterine contractions. Therefore, rosemary is not appropriate for use during pregnancy.

Sage is Safe for Dogs and Helps Prevent Infection

Sage is an excellent remedy for infection or ulceration of the mouth, skin, or digestive tract. Most of its antimicrobial activity is attributable to its content of thujone, a volatile oil that is effective against a wide variety of harmful bacteria. In the mouth, a strong sage tea or tincture is useful for treating or preventing gingivitis, as well as infection that may be secondary to injury or dental surgery.

For mild bacterial or fungal infections, sage tea can be added to drinking water. Make it by steeping one tablespoon of the dried leaves in a cup of near-boiling water. Stir the mixture frequently until it has cooled to lukewarm. Strain out the plant material, but don’t discard it if you are treating a localized gum infection; it can be used as a poultice by applying the wet herb directly to the affected area.

If your companion doesn’t like the taste of sage tea, try sweetening it with a little honey (which has healing properties as well). The sweetened tea can be fed at a rate of one fluid ounce per 20 pounds of your dog’s body weight, twice or three times daily. Used in the form of a rinse, sage tea is useful for bacterial or fungal infections of the skin, and is especially wonderful when mixed in equal parts with rosemary and thyme teas.

Thyme is Good for Dogs and an Alternative to Sage

Most of the medicinal activity in thyme is attributable to the volatile oils thymol and carvacrol. Thymol is a very good antiseptic for the mouth and throat, and useful for fighting gingivitis. In fact, thymol is used as an active ingredient in many commercial toothpaste and mouthwash formulas.

Combined with thyme’s infection-fighting qualities are its antitussive and expectorant properties, making the herb useful for raspy, unproductive coughs that are secondary to fungal or bacterial infection. As an antispasmodic, thyme helps ease bronchial spasms that are related to asthma.

A glycerin tincture, or an alcohol tincture that has been sweetened with honey, serves well for most internal applications; use one-quarter of a teaspoon (1ml) for each 30 pounds of your dog’s body weight, fed as needed up to twice daily. A cooled tea will work too, provided it has been brewed with near-boiling water to draw out the volatile oil constituents. One teaspoon for dogs, ¼ teaspoon for cats, fed directly into the mouth two to three times daily.

For infections of the mouth or as a preventative against gingivitis, the tincture or a very strong tea can be directly applied to the gum lines or infected sites with a swab. A thyme tea skin rinse, made by steeping one tablespoon of the herb in one quart of near-boiling water) is useful for various fungal or bacterial infections of the skin, especially if combined with equal parts of chamomile tea.

Chamomile is another kitchen herb that is so incredibly safe and useful, that I’ll devote an entire article to it in a future issue.

Securing Seacure

Can you imagine a food so easy to assimilate that even the most impaired digestive tract absorbs it on contact?

Now imagine that this food speeds the healing of wounds throughout the body, repairs digestive organs, alleviates nausea and vomiting, stops diarrhea, supports the liver during detoxification, reduces the side effects of chemotherapy and possibly helps prevent or reverse cancer, prevents toxemia in pregnancy, rescues newborns from Fading Puppy Syndrome, helps elderly dogs maintain their strength and stamina, helps all dogs recover from chronic and acute illness, stimulates hair growth, reduces urinary tract infections, reduces or eliminates allergic reactions, prevents hot spots, improves mobility, reduces pain, and even enhances the effectiveness of homeopathy and herbal therapies.

That miracle food exists, and dogs love its taste. They should. It’s an odoriferous powder made from fermented fish.

Seacure was Invented to Combat Hunger

Forty years ago, scientists at the University of Uruguay, who were searching under the direction of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences for a way to feed starving children, perfected a fermentation technology that predigested fish, creating a highly absorbable protein supplement. Fresh, deep-sea whitefish fillets were broken down by marine microorganisms, then dried to create a fine powder.

During the 1970s and 1980s, physicians in Uruguay and adjacent countries used the formula to save the lives of thousands of premature, underweight, or malnourished infants. In clinical studies, these infants showed significant improvement in weight and immunity factors (globulin and gamma globulin levels) within 30 to 60 days. No premature infants receiving the fish formula developed edema. When other infants developed edema, use of the formula caused its disappearance within 48 to 72 hours.

Uruguayan researchers tested a combination of two-thirds mother’s milk and one-third fermented fish powder for premature infants and found that the fish powder improved assimilation and weight gain. The researchers reported a “most remarkable” disappearance of dysergia (lack of motor control due to defective nerve transmission) in cases of dystrophy. When given to pregnant women, the supplement was also found to be very effective in promoting normal birth weights (preventing low birth weights).

When the fish supplement was fed to babies who were allergic to milk or had other food allergies, their allergic reactions disappeared, along with symptoms such as acute and chronic diarrhea or blood-based immune disorders. Soon physicians were documenting health benefits for patients with all kinds of illnesses. However, when the formula’s key developer died, production stopped.

Donald G. Snyder, Ph.D., then director of a Fisheries Research Laboratory at the University of Maryland and a member of a U.S. National Research Council committee on protein supplements, formed a partnership to obtain the technology and produce the powder, which he named Seacure®.

Seacure, which is made from Pacific whiting caught in the Pacific Northwest, contains beneficial omega-3 fatty acids and other fish nutrients, but its amino acids and peptides (the fundamental constituents of protein) are its primary healing ingredients.

(EDITOR’S NOTE: Proper Nutrition, Inc. is the maker of Seacure® and licences its use in other supplements. Still other supplement makers manufacture and sell similar biologically hydrolyzed whitefish products. All of the product studies and research referred to in this article were conducted using Seacure®.)

Seacure is a Different Kind of Protein

Most protein supplements sold in the United States contain ingredients that can be difficult to digest and assimilate, such as meat, animal skins, milk, eggs, or soy. Dr. Snyder (who recently passed away) felt these proteins were inferior sources for supplements.

“Often,” he explained, “these raw ingredients are contaminated or of low quality, such as rejected eggs or excess milk, or they are processed using harsh physical or chemical methods. Severe drying methods are often used, resulting in a deterioration in the final protein quality. And protein from the byproducts of processing may be of questionable value to begin with. The key thing is the quality of a supplement’s protein and the pre-digestion factor that makes it available to the body.”

All proteins are formed from long chains of compounds called amino acids. The body (both human and canine) can synthesize or manufacture some amino acids, but others are called essential because the body cannot manufacture them and they must be provided by protein in the diet. This use of the word “essential” can be confusing, for many amino acids are necessary for optimum health, but only those that must be provided by protein in food are called essential.

The World Health Organization established a model or ideal balance of the essential amino acids (isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, cysteine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, threonine, tryptophane, and valine) in terms of milligrams of amino acid per gram of protein. The value of the protein provided by Seacure exceeds the model in every category. In addition, the quality of its raw materials exceeds that of other protein supplements, and its assimilation requires no digestive effort from the dogs and people who take it.

Seacure for Dogs

At Proper Nutrition, Inc., the company he founded, Dr. Snyder worked closely with marketing director Barry Ritz in research and development. “We receive many reports from veterinarians,” says Ritz, “indicating that Seacure’s benefits are as dramatic for dogs as they are for people.”

For example, he explains, malnourished, premature puppies have no ability to handle intact, complex protein. Seacure’s predigested protein can literally save their lives. In addition, it nourishes growing puppies, adult dogs, and any animals with malabsorption problems, such as sick or elderly dogs.

“It is no exaggeration,” Ritz observes, “to say that any dog of any age can benefit from Seacure’s high-quality predigested protein. The results, which are cumulative, include everything from improved wound healing to a thicker, glossier coat; a calmer disposition; improved digestion; and improvements in coordination, stamina, range of motion, and athletic performance.”

According to Ritz, veterinarians and dog owners report that doses of 6 to 12 capsules a day cause shaved fur to grow back in record time, broken bones and other wounds to heal quickly, and ailments like allergies, diarrhea, and inflammatory bowel disease to improve or completely disappear. Even dogs with autoimmune disorders like lupus have regained their mobility and appetite. Some owners report pigment corrections or a reduction in an older animal’s gray hairs.

“Seacure also helps dogs with diabetic leg ulcers and other slow-healing wounds. It speeds recovery from surgery, bite wounds, cuts, abrasions, burns, pulled muscles, and sports injuries. Dogs in obedience or agility class are more attentive as well as more efficient in their movements. And dogs with arthritis or joint pain just keep improving,” Ritz says.

Most dogs tolerate Seacure well. Dogs with kidney disease, for which low-protein diets are often recommended, should not have a problem because Seacure is already predigested and does not add stress to the kidneys.

The levels of mercury contained in Seacure are below the threshold of detection in mercury toxicity tests, 0.01 parts per million.

Understanding Detoxification

In our polluted world, detoxification has become a health buzz word. Like people, dogs are said to benefit from supplements and dietary changes that stimulate the removal of chemical residues, stored toxins, and stagnant wastes.

But too-rapid detoxification can be painful as well as harmful. Symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, dizziness, confusion, overwhelming fatigue, and skin eruptions such as hot spots often accompany rapid weight loss, the switch from commercial pet food to a raw, home-prepared diet, the use of herbs and supplements that cleanse the liver and blood, the acute phase of any illness, treatment with conventional drugs, treatment for parasites, or exposure to environmental toxins.

We often forget that detoxification is an ongoing body process. It never stops. If the body receives the nutrients it needs to break down and remove waste products well, it maintains itself in a state of health. If the process is impaired, health suffers. Unfortunately, many if not most of America’s dogs are overwhelmed with the ongoing burden of detoxification.

During the first stage of detoxification, the body identifies and separates waste products and toxins from the blood and lymph. Water-soluble material that can be excreted goes to the kidneys. Dehydration complicates the detoxification process, which is why access to clean drinking water is so important for dogs.

In Phase I of detoxification, during which waste products are made water-soluble and sent to the kidneys, the liver uses antioxidants and key minerals such as vitamins A, C, and E, bioflavonoids, selenium, copper, superoxide dismutase (SOD), zinc, and manganese. In phase II, the liver needs glucuronic acid, sulfates from glutathione, acetyl-cysteine, and the amino acids taurine, arginine, ornithine, glutamine, glycine, and cysteine.

When a dog is deficient in either Phase I or Phase II nutrients, backups and spillovers occur. Partially processed toxins traveling through the bloodstream may find a home in fatty tissue, or they may stay in the blood, infect healthy tissue, and cause new illnesses.

Many herbs and supplements are recommended for canine detoxification support, but few address the body’s need for amino acids. Seacure not only fills that gap and reduces the symptoms of detoxification, but also literally heals damaged organs and improves the dog’s digestion. Like people, dogs can suffer from leaky gut syndrome. Tiny injuries to the intestinal wall cause it to become too porous, allowing large molecules of undigested protein, bacteria, and microorganisms to migrate from the digestive tract to the rest of the body, which stresses and impairs the liver, pancreas, and immune system. Leaky gut syndrome is associated with food sensitivities, allergies, hyperactivity, and autoimmune disorders.

Giving meat and other high-protein foods to dogs with leaky gut syndrome or other digestive disorders doesn’t help because the damage prevents the food from being completely digested and assimilated. Seacure doesn’t require digestion, so it allows digestive organs to rest while supplying the amino acids and peptides needed for tissue repair and recovery.

Even dogs who suffer from vomiting, chronic diarrhea, and wasting diseases can usually accept Seacure, which can be mixed with water and administered with a dropper or feeding syringe. Seacure is not yet available as a powder for the convenience of feeding dogs and cats, but most dogs are happy to swallow the capsules whole. Or, the capsules can be opened and the powder sprinkled over food or mixed with water.

Whether you make Seacure part of your dog’s everyday diet or use it for a short time to speed recovery from an illness or accident, Uruguay’s solution to Third World famine problems can help your dog lead a longer, healthier life.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Favorite Remedies Revisited”

Click here to view “Supplements and NSAIDs for Dogs”

A regular contributor to WDJ, CJ Puotinen is also the author of The Encyclopedia of Natural Pet Care, Natural Remedies for Dogs and Cats, and several books about human health, including Natural Relief From Aches and Pains.

Download the Full March 2003 Issue

Join Whole Dog Journal

Already a member?

Click Here to Sign In | Forgot your password? | Activate Web AccessShipping Your Dog Cargo While You Fly

-By Pat Miller

A client called me recently, seeking my advice. She is moving across the country, and wanted my recommendation on which airline to use to fly her Lab mix.

“I can’t give you one,” I told her. “I simply would not ship a dog by air, so I haven’t made any effort to keep track of which one might be safest.”

She wasn’t happy with my response. “But I have no choice,” she said, “I have to ship him.”

I told her that for me, flying a dog cargo was not a viable option, and that if I were in her position I would simply, somehow, find another way. I’m sure she was nettled by what she thought was my inappropriately stubborn refusal to give her the information she wanted.

The fact is, the information is almost impossible to come by. Unbelievably, neither the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) nor the airline industry keeps records of the number or percentage of animals that are lost, injured, or killed during air cargo transport. Any figures that do get reported are regarded as suspect by one or another player in the industry.

For example, the American Humane Association estimates that of the approximately two million animals who travel by air each year, some 5,000 are lost, injured, or killed. The Air Transport Association contests that number, but can’t deny that animals are sometimes harmed during transport. Because there is currently no disclosure of such incidents required by law, however, no one knows the true number.

We pet owners tend to hear about only the sensational cases that make it into the newspapers, such as the five German Shepherds, trained for law enforcement work, who died traveling on a Delta Airlines flight from Georgia to Ohio in May 2002, or the cat who disappeared somewhere between Canada and San Francisco while being shipped on an Air Canada flight in August 2002 (the cat’s heavily damaged carrier arrived, however).

We don’t hear about the less dramatic (but hardly less damaging) cases. Our dogs can’t tell us about their exposure to the elements – excessively hot or freezing cold temperatures they may experience in the cargo hold and on the tarmac. We don’t hear about pet carriers falling off luggage conveyor belts or being tossed around by careless or hurried baggage handlers. Nor do we hear about animal carriers that, just like other luggage, get loaded on the wrong flight and end up far from their intended destinations, with no one available to comfort or allow the distressed animals to relieve their full bladders or bowels. And when a puppy is shipped to us from a distant breeder, we never know for sure if his fearful personality is genetic, or stems primarily from the trauma of travel, especially if he was shipped during one of the several “fear periods” that can occur during the first year of a puppy’s life.

The airline industry doesn’t help its public image when it resists legislation and regulations intended to improve animal safety during air travel. New rules, ordered by Congress and proposed by the FAA, are supposed to go into effect by the end of this year, but are being met with vociferous objection from at least Delta, Northwest Airlines, and the Air Transport Association. The rules would, among other things, require closer observation of animals in flight and reporting of information regarding any incidents where animals are hurt, lost, or killed, so that consumers (ostensibly) would be able to choose an airline with the best safety record. (For more about this legislation, see sidebar below.)

First things to know

Personally, even if I had reliable information about the airline’s safety record, I doubt I would risk flying my dogs – unless I can fly them in the cabin with me, as I did with my Pomeranian last September, to attend the Association of Pet Dog Trainers’ annual conference in Portland, Oregon. As I learned, there is a lot that a person should know before she carries a dog onto an airplane, too! Even though I anticipated many of Dusty’s training issues that the experience would test, and had spent a significant amount of time getting him used to staying in his new airline-approved, soft-sided carrying case, there were many other aspects of our journey that were, at least, an inconvenience and could have been a major problem for Dusty and me. The first thing I learned is that the airlines charge a fee – usually about $75, each way – for each carry-on pet. This, despite the fact that they will not be handling the dog’s carrier at all! (Imagine if you had to pay $75 for any other carry-on luggage!)

I also found out that all of the airlines have a limit on how many animals a single person can carry (usually, only one pet per person) and a limit on how many animals can be on each flight. Most airlines will accept no more than two or three pets on any given flight. If you are headed toward a large dog-related event, then, you need to make your dog’s reservations very early to ensure his place under your seat.

Next, I learned that I would need a certificate from a veterinarian, advising the airline that my dog was healthy and completely vaccinated. The airline I used required this certificate to be issued no more than 10 days before my trip. Because I was going to be away for a week and the 10-day rule applied to the trip home as well, I made the health exam appointment with my veterinarian for the day before I left home. Otherwise, I would have needed to find a veterinarian in Portland to examine Dusty and issue another certificate for the trip home. Most veterinarians charge between $25 and $50 for the health exam, and an extra $10 to $25 for the certificate.

Also, those dog owners who use a reduced vaccination protocol should discuss the vaccination-reporting portion of the health certificate with their holistic veterinarian long before they plan to bring their dog on a plane. The certificate is a legal document that requires the veterinarian to swear (with his or her medical license at stake) that the dog is fully and currently vaccinated. As we’ve discussed in numerous articles, many holistic veterinarians suggest a reduced vaccination schedule for most dogs, using vaccine antibody titer tests to confirm that the dogs possess adequate antibody levels to convey protection from disease (see “Take the Titer Test,” WDJ December 2002, and “Current Thoughts on Shots,” August and September 1999).

And, of course, vaccinating the dog right before a potentially stressful trip is ill-advised.

First things to practice

Weeks (if not months) before you head to the airport with your carry-on dog, you need to invest in an appropriate airline-approved carrier (we have a strong recommendation for one; see the sidebar below). Then, you need to spend lots of time having your dog practice getting in and out of it, and spending significant amounts of time in it. This is to ensure that she will be physically and emotionally comfortable in the carrier for extended periods of time.

Introduce your dog to the carrier slowly; don’t ever force him in and zip it up quickly, which would be enough to convince many dogs to dread the carrier forevermore. Leave the carrier open, with a few treats sprinkled inside it, in your living room for a day or two so he can approach and smell it all on his own. Then, while you are reading or watching television one evening, toss treats onto the floor near the carrier, and then inside it, so your dog has to enter it, at least partway, to get the treat.

You can speed this process along by using a reward marker (such as the Click! of a clicker or the word “Yes!”) every time your dog goes even a little way into the carrier, followed by a yummy treat. Reward him for going farther and farther inside, and for increasingly long visits to the carrier before you close him in – and make those first “captures” very brief.

When your dog is comfortable staying in the closed carrier for a minute or so, give him a Kong toy stuffed with delicious treats; you can freeze the food-filled Kong to make it last even longer.

Monitor your dog closely while he’s in the carrier so you can let him out before he starts whining or exhibiting any anxiety about being closed in. If you free him immediately after any sort of outburst, you may set yourself up for further displays of whining, barking, or scratching to get out.

When he’s comfortable spending significant periods in the carrier, practice carrying him in it. Even a brief practice session may influence your selection of other carry-on items; even little dogs get heavy!

Cabin fever

I felt well-prepared but nervous before my first flight with a dog. Dusty, in all his fluffy 8 pounds and 13 years, had never been on a plane. We had driven to the APDT conference in upstate New York the year before and earned two of the three Rally legs we needed to get his title. I really wanted us to get that last Rally leg while Dusty was still capable of doing it. Besides, I had enjoyed having dogs with me at the conference the previous year and was really looking forward to his company.

Two days before we were scheduled to leave, just to be sure, I decided to call the airline to check on Dusty’s reservations, which I had made weeks before. To my dismay, the airline reservations person told me they had no record of the reservations! Fortunately, there was still an opening on my flight, but it confirmed my opinion that “you can’t be too prepared.”

The morning of our departure finally arrived. I carefully packed Dusty’s health certificate, treats, and water for the trip, as well as a stuffed Kong with extra stuffing materials in case he decided to switch into “demand barker” mode. I loaded my luggage into the car, then Dusty’s carrier, and finally, Dusty. He would be in that carrier for several hours – I didn’t want to shut him in until the last possible moment.

I parked in long-term parking at the Chattanooga airport; fortunately, the airport in our town is small enough that even long-term parking is just a brief walk from the ticket counter. I checked one suitcase through, and then we were on our way, Dusty prancing happily by my side through the airport.

At the security check, Dusty had to go into his carrier. The security officer reminded me several times that “the dog” could not come out of his carrier past this point, until we reached our destination. Dusty’s ears flattened a little at my cue to “go to bed,” but he hopped in for a treat, and I zipped him up, leaving the nylon cover rolled up on one side so he could see out. Taking a deep breath, I hoisted his bag over my left shoulder, picked up my purse with my left hand, grabbed my laptop case with my right, and headed for the gate.

Dusty wasn’t very happy and I didn’t blame him. Although I had acclimated him to the carrier, I had neglected to practice carrying it with him inside. I wasn’t very happy either; I had not realized how heavy the darn thing was once it was packed with one small dog and his various accessories. The carrier bounced and shifted as I walked, and I could feel my little friend trembling in the carrier at the same time I felt the crate strap biting into my shoulder. Other travelers, not aware of my precious cargo, came precariously close to bumping into him, which stressed us both even more.

Since I had allowed myself lots of extra time, I was able to experiment with my bags until I found a more comfortable way to carry everything. Let this be a warning: Try out all equipment in full dress rehearsal prior to actually using it.

We made it onto the plane without any new stress, and his carrier fit (just barely!) snugly under the seat in front of me. I had carefully measured it ahead of time to be sure it met the airline size limit of 17 inches long, 16 inches wide, and 10.5 inches high.

Dusty rested quietly without a peep throughout the first leg of the trip. None of the engine noises or plane vibrations seemed to bother him a bit. Seems there are some advantages to being almost totally deaf!

When flying with a carry-on dog, it is best to get a direct flight if at all possible. Of course, one of the disadvantages of a small friendly airport like Chattanooga is that you can’t get most places from here. We changed planes in Cincinnati, and had a long hike from one gate to the other. My shoulder became more and more sore.

The remainder of the trip was quiet. As soon as we exited the Portland airport I rescued Dusty from his crate and he gratefully lifted his leg for several minutes on a bush.

Not over until it’s over

The conference was enjoyable for both of us. Dusty loved sitting on my lap through workshops, and enjoyed treats and pets from other conference-goers who had left their canine companions at home and needed a “dog-fix.” He even enjoyed his first-ever professional dog massage! Halfway through the conference his shoulder popped out of place and he was walking on three legs. His chances for earning that last Rally leg were fading, until a five-minute massage miraculously fixed the problem.

When the week was over, Dusty had indeed won his Rally title, as well as an award at one of the three trials for Highest Scoring Dog Adopted From a Shelter, and High Scoring Senior Dog. He was retiring from the Rally ring with honors, and I was looking forward to getting us both back home.

Seasoned travelers now, we had far fewer anxieties about the trip. We made it home almost hitch-free.

Knowing that Dusty would travel well, I packed only the bare necessities in his travel carrier, which lightened the load on my shoulder. I had perfected my technique for holding the carrier, which also reduced the wear and tear on both of us. The Portland to Cincinnati jaunt was trouble-free, and with one leg of the journey left to go, I confidently climbed onto the small plane that would bring us home, walked to my seat and set the carrier down to slide it into its space.

Uh-oh. It didn’t fit. I pushed on it, flattening it as much as I could without infringing on Dusty’s space. It wouldn’t go, and stuck out about six inches. The flight attendant came by doing her last minute check.

“It has to go all the way under the seat,” she said.

“It won’t fit,” said I.

“We have a closet up front I can put it in,” she said.

“Not unless I can fit in the closet with him,” I answered, calmly but firmly.

“Then he’ll have to go in cargo,” she said.

“Not unless I go in cargo with him,” I answered, calmly but firmly.

“I’ll have to go get someone else,” she said, looking distinctly worried.

She brought back a male flight attendant, who went through the same litany of options for where Dusty’s carrier could go if it couldn’t fit under the seat. I gave him the same calm, firm answers. I finally reached down and managed to smoosh the carrier under the seat another two inches so it was sticking out only four inches, and he agreed that Dusty could stay there. Good thing, because I wasn’t looking forward to spending the flight in the cargo hold or in a closet!

I have to admit, while it was nice having Dusty with me at the conference, I would think long and hard before flying again with him or another small dog. It was stressful on both of us – especially when I thought I might have to change planes to prevent the airline from whisking Dusty into the cargo hold because the carrier wouldn’t fit under my seat.

People who travel more frequently than I may be more relaxed about the entire ordeal. But that doesn’t mean they can be any less vigilant about protecting their dogs from unexpected developments en route.

Pat Miller, WDJ?s Training Editor, is also a freelance author and Certified Pet Dog Trainer in Chattanooga, Tennessee. She is the president of the Board of Directors of the Association of Pet Dog Trainers, and published her first book, The Power of Positive Dog Training, in 2002.

Canine Glandular or Organ Therapy

The premise seems simple – if your dog has liver problems, feed him liver. What if it’s a kidney, thyroid, or adrenal problem? Then feed kidney, thyroid, or adrenal tissue. This is, in its simplest form, glandular or organ therapy.

The process has become much more refined over the years. Now your dog can experience the benefits of glandular therapy even when you can’t find the raw glands or other organs to feed him. Now, glandulars (the common term for products containing animal cells even if they aren’t from glands) are available in tablet, capsule, and liquid form, depending on the manufacturer.

The use of tissue from one species to help rebuild damaged tissue in another species dates back thousands of years. The papyrus of Eber, the oldest known medical document from about 1600 BC, describes the injection into humans of preparations made from animal glands. In the Middle Ages, the physician Paraclesus wrote and practiced the maxim “heart heals the heart, lung heals lung, spleen heals spleen; like cures like.”

While these crude forms of glandular or cell therapy were used for hundreds if not thousands of years, the techniques weren’t significantly refined until the 19th and 20th centuries.

Hormonal influence

There are a number of theories about exactly how glandulars work. The earliest medical hypothesis was that the glandular preparations supplied the hormones that the patient’s damaged glands failed to produce themselves. This led to the isolation of those hormones and the manufacture of their synthetic equivalents, and was how the drugs hydrocortisone and prednisone were ultimately discovered.

Researchers found they could maintain the lives of adrenalectomized cats by giving the cats adrenal extracts. (In fact, the Pottenger cat study, which most raw feeders are familiar with, was originally designed to help Pottenger regulate the potency of an adrenal extract he was manufacturing. The nutrition study evolved out of his observations of the adrenalectomized research cats.)

After discovering that the extracts could keep the cats alive, the key hormone cortisol was isolated. From this discovery, scientists developed synthetic hydrocortisone and prednisone to mimic the activity of naturally occurring cortisol. However, patients who receive these very narrow-focus drugs (which lack all the other potential activity of the glandular tissue) often experience harmful long- and short-term side effects. Incorporating the whole tissue, or extracts of tissue, must therefore have additional value.

It turns out that Paraclesus’ thinking was right on target. It turns out that cells are attracted to and nourish “like” cells – even if they are from a different species. By tracing stained or radioactive cells, research has shown repeatedly that the injected cells accumulate in the like tissue of the recipient.

For example, one study conducted in 1979 by T. Starzyl, showed that when animals with chemically damaged thyroids were given thyroid cells, there was a marked regeneration of the damaged thyroids.

In 1931, Paul Niehans the modern discoverer of cell therapy (injection of tissue into a patient rather than oral ingestion) came upon the treatment quite by mistake. A colleague of his had accidentally removed the parathyroid glands from his patient. Dr. Niehans was called upon to transplant bovine parathyroid glands into the woman. Because the woman was convulsing so violently and concerned that she wouldn’t survive the transplant surgery, he quickly sliced up the glands into minute pieces and injected her with them. The woman not only recovered, but lived another 30 years.

“Tissue decoys”

Another interesting benefit of glandulars is their use as an apparent tissue decoy. In 1947, Royal Lee (founder of Standard Process, a well-respected supplement manufacturer) and William Hanson published a book, Protomorphology, Study of Cell Autoregulation, in which they presented their theory that when taken orally, protomorphogens (PMG) – portions of cellular chromosomes – speed the elimination of tissue antibodies. This concept is now referred to as oral tolerization and is being researched extensively in the treatment of the human autoimmune diseases including rheumatoid arthritis, type I diabetes, uveitis, and multiple sclerosis.

“When the body is attacking itself and you give a PMG decoy, the body will attack [the decoy] rather than the organ,” explains Arthur Young, DVM, CHO, a holistic veterinarian based in Stuart, Florida. By stopping the autoimmune attack on the body’s own organs, you give those tissues a chance to recover.

This is what contemporary researchers are finding with their experiments using glandulars to combat autoimmune diseases. In the research on MS, when bovine myelin is administered orally, the autoimmune process against the body?s myelin basic protein is suppressed.

Nutritional value, too

In addition, glandular supplements provide a wide variety of nutrients and enzymes. These amino acids, peptides, enzymes, and lipids may directly help with the functioning of the glands and organs. Besides that, they’re good nutrition.

“Glandulars are one of the primary modalities I work with,” says Gerald Buchoff, BVScAH, owner of Holistic Housecalls for Pets and vice president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association. “I find most pets have imbalances and I have three things I use to rebalance in my bag of tricks: chiropractic, acupuncture, and nutrition. Glandulars are a key part of nutrition.”

When to use glandulars

Many holistic vets use glandular supplements in combination with other modalities, such as homeopathy, traditional Chinese medicine (including Chinese herbs and acupuncture), flower essences, and chiropractic. Dr. Young feels that rather than competing with the energy medicine of homeopathy, glandulars work synergistically with the modality. He says, “Glandulars support the organ systems involved while homeopathy helps the body to heal itself.”

For instance, with a dog exhibiting signs of hypothyroidism, Dr. Young will use a product such as Standard Process’ “Thytrophin PMG®” to support the thyroid gland and act as a decoy to possible autoimmune activity that could be damaging the gland. Because thytrophin has been processed to remove the hormone thyroxine, it doesn’t impact the complex and sensitive pituitary-thyroid feedback system. In contrast, the medication Soloxine replaces endogenous thyroxine, thereby suppressing the thyroid’s ability to produce hormones itself.

In combination with the glandular supplementation, Dr. Young completes a thorough homeopathic workup and prescribes the appropriate homeopathic remedy. The remedy is chosen to help balance the body so that it can heal itself. Dr. Young has found that using this combination of glandulars and homeopathy benefits a wide variety of health issues, including inflammatory bowel disease, skin problems, liver disease, fertility issues, and even cancer.

In Dr. Buchoff’s experience, diseases of the kidney and liver respond the best to glandular therapy. Contrary to Dr. Young’s experience, Dr. Buchoff has found that dogs with hypothyroidism can benefit from glandulars, but usually need to continue taking conventional medications as well. “Hypothyroidism is frustrating that way,” he adds.

Spay incontinence is one of the common problems that Ihor Basko, DVM, of Kapaa, Hawaii, treats with glandulars. He’s seeing the problem more frequently as animals, particularly shelter animals, are spayed at younger and younger ages. He has had the most success with “Resources Incontinence Formula” made by Genesis Ltd. This product’s ingredients include bovine ovary and herbs such as licorice and wild yam, which contain phytoestrogens. In his opinion, this supplement is very effective and safer than the estrogen (usually DES) or PPA (phenylproanolamine) commonly used in conventional veterinary practices.

Dr. Basko has found that glandular supplements are also effective for treating geriatric dogs experiencing cognitive disorders, and he far prefers this approach to the conventional pharmaceutical drugs used for cognitive disorders in aged dogs. He recommends adrenal glandulars in particular for these dogs, finding that they can give older animals a boost.

In addition to addressing specific issues such as liver, kidney, or thyroid disease, Dr. Buchoff recommends using supplements with glandulars as a preventive to keep the endocrine system balanced. He recommends that all of his patients receive the gender-specific version of the Standard Process product, Symplex® (Standard Process makes a male and female version). This product is a combination of bovine ovary or orchic, adrenal, pituitary, and thyroid PMG extracts. He also recommends Catalyn® to patients not on a raw diet.

Other suggestions

Your veterinarian should conduct blood tests to establish pretreatment values for hormone levels and other indicators, reminds Dr. Basko. Be sure to follow up with additional testing to confirm whether or not the therapy helps. If you don’t notice results initially, the dose may need to be increased. Not enough has been done to determine optimal doses of these supplements, he adds.

Despite a possible need for more research on dosing for animals, glandular therapy is quite safe. “There are no contraindications, glandulars aren’t drugs or toxins, but naturally occurring nutrients,” explains Dr. Young. Do be sure to use fresh products from quality suppliers. And don’t over-supplement with glandulars; more isn’t always better.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “Help for Dogs with Hypothyroidism”

Click here to view “Case of the Missing Hormones”

Click here to view “Symptoms of Addison’s Disease”

Shannon Wilkinson is a TTouch practitioner who lives with two dogs, two cats and a husband in Portland, Oregon.

Hydrotherapy and Aquatic Exercise for Canine

-By C.C. Holland

Hydrotherapy and aquatic exercise are the hottest new tools in canine physical rehabilitation. And that’s not just a jump in a lake. Today’s cutting-edge therapists work with veterinarians’ referrals and use sophisticated underwater treadmills and other specialized equipment to provide rehabilitation for a variety of medical conditions. And they are frequently able to achieve better results in less time than through the recovery regimens prescribed by more conventional veterinary practitioners.

We reported on the rising use of heated therapy pools for rehabilitation in the October 2000 issue of WDJ, and described how therapists partially support and guide canine clients through a series of gentle exercises in the warm, muscle-relaxing water. The latest therapy tool also uses a warm pool, but adds an underwater treadmill. The therapist can effectively reduce the amount of body weight the dog must carry as he walks on the treadmill simply by increasing the depth of the water. As the dog progresses, the water height can be reduced to create more load on his limbs.

For example, in an underwater treadmill apparatus with the water level at shoulder height, the dog’s rear paws support less than a third of his weight, compared to the usual two-thirds on land. As he gains strength, he’ll work in a shallower pool, against a current, or with the treadmill tilted at varying degrees of incline.

Everyone’s happy

One such leading-edge therapy center is SOL Companion, in Oakland, California. Sabina, a four-year-old Rottweiler, is one of the center’s clients. At a recent rehabilitation session she limped across the floor of one of the treatment rooms, declining to put weight on one of her hind legs.

“We think it’s something neurological,” commented Nina Patterson, the physical therapist working with Sabina. Whereas in most cases it’s difficult to rehabilitate a gimpy leg when your patient can’t or won’t use the limb, this is a case where the underwater treadmill excels.

Veterinary technician Amy Mayfield led Sabina into a large box enclosed with thick, clear plastic. A standard-looking treadmill sat on the bottom. Sabina stood on the treadmill, her weight on three paws, eyeing the liver treats that Mayfield held at the ready. Mayfield reached for the controls, and slowly, heated water began to seep into the treadmill chamber. Sabina waited patiently. When the water reached about chest height, the water flow ceased, and the treadmill began to move slowly.

Sabina moved along with it, her injured paw touching down tentatively at first, then more confidently as she strode along. When she exited the unit after a 15-minute session, her limp had diminished noticeably.

Sabina’s story helps explain why enthusiasm is growing about the underwater treadmill, which was first used on canines about four years ago. Julie Stuart, MS, PT, at Tufts University School of Veterinary Medicine, says her dream setup for rehab includes an underwater treadmill.

“It’s great for orthopedic dogs, dogs with arthritis or with hip dysplasia,” she says. “In water, they can exercise pain-free because it takes away the weight bearing. The buoyancy makes them bear less weight on their joints, yet it’s resistive.”

That combination of buoyancy and resistance makes using the underwater treadmill attractive in therapeutic work. John Sherman, DVM, an affiliate of North Carolina State College of Veterinary Medicine in private practice, has used a unit for nearly two years.

“It’s a powerful tool,” he says. “Let’s say a dog weighs 100 pounds on land. You could have him walk in water so he’d weigh only 40. You can get dogs with an injury or surgical repair walking and returning to function quicker.”

The water in these high-tech tools is heated for comfort – the temperature in the unit Sabina used is kept between 86 and 90 degrees Fahrenheit – and treated with a chemical such as chlorine or bromine to reduce bacteria levels.

Technicians can adjust the intensity of exercise by adjusting the treadmill’s speed and angle or by introducing a slow-flowing current for the dog to swim against. They harness dogs for safety and closely monitor them throughout the session. The pool has full filtration and the motor is safely enclosed away from water.

In addition to altering the weight he bears, the variable water level also changes the percentage of weight he carries on his front and rear limbs. When a dog walks on land, his forelegs bear 64 percent of his weight and his rear legs, 36 percent, says Patterson, the physical therapist at SOL Companion. In water at hip level, those percentages change dramatically.

“In the water, the rear legs almost float and bear only 28 percent of the dog’s weight, while the forelegs now take up 72 percent of the load,” Patterson explains.

Says Donna Chisholm, PT, who also works at SOL Companion, “You get all the benefits of buoyancy along with a reduction of compression forces. Using the underwater treadmill addresses all areas: balance, stability, conditioning, strength.”

Deep issues

If so many canine rehabilitation specialists are gung-ho about the units, why aren’t they everywhere? According to Allan Dahl, director of aquatic therapy for the manufacturer Ferno, only 53 of the company’s K9 Underwater Treadmill Systems have been sold since production began four years ago.

One factor may be price. Ferno’s underwater treadmills range from $14,500 to $50,000. At Tufts, Stuart cited cost as the reason she chose to purchase a swim spa/pool instead.

Dahl believes the bigger issue is simply the fact that canine rehabilitation itself is relatively new. Only an estimated 30 to 40 facilities in North America are devoted specifically to dogs. “Rehab is becoming an important tool in veterinary medicine,” he says. “But getting the vets to accept that therapy is important is taking some time.”

Dr. Sherman agrees. Rehabilitation is a very new science for his profession, he says. When he graduated from veterinary school in 1993, students learned to perform a surgery and then crate the dog for six weeks, with time outside only for elimination. The dog would then walk on leash for another six weeks.

“That was it,” he says. “That was rehab. Or you swam them, but really, swimming for a hind-limb injury is just not that effective a therapy.”

That mindset began to give way when human physical therapy became popular. Some veterinarians and physical therapists began considering translating human therapeutic modalities to the canine world. One was Laurie McCauley, DVM, an Illinois veterinarian in private practice. Four years ago she approached Ferno, which at the time was making underwater treadmills for human and equine use.

“They thought I was crazy, but they worked with me,” she says. “It’s such great exercise, safe for a 90-year-old lady with a hip replacement. So I thought it would be great for arthritic dogs.”

Dr. McCauley gave Dahl a wish list. In return, Ferno developed its first canine underwater treadmill, a unit that attached to her existing pool and used a Jet-Ski lift to vary the water height. Today, Dr. McCauley has two underwater treadmills at her TOPS Veterinary Rehabilitation center in Grays Lake, Illinois, and said about a dozen dogs a day benefit from them.

“I’ve had dogs with neurological injury that have used their legs a full two weeks in the water before they used them on land,” says Dr. McCauley. “A lot of the arthritic dogs do great with it. Their owners tell me they go home and are running up and down stairs, doing things they haven’t done for six months.”

Echoing Dr. McCauley’s enthusiasm is David Levine, a certified orthopedic physical therapist and adjunct associate professor at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga’s College of Veterinary Medicine. Dr. Levine is also an orthopedic certified specialist (OCS) and certified by the American Board of Physical Therapy Specialties. Levine was an early adopter of the underwater treadmill and worked with Ferno to design and modify the first units.

“I think early on, especially early post-operatively, it’s a really wonderful rehab tool to get (a dog) to start using a limb a lot easier than we normally could have outside, with just walking,” he says. “It’s enhanced our ability to rehabilitate post-op dogs more quickly and to a higher level.”

Of course, the people operating the treadmills need to be knowledgeable about their work. “The underwater treadmill, like anything, is just a tool to be used,” says Dr. Sherman. “If you just put a dog in there and expect him to get better, you can get into trouble. You have to give every patient a full physical exam, see where he is in the healing process and monitor his progress. In the wrong hands, if you just turned it on and didn’t know what you were doing, that would be a problem.”

Part of the plan

Every therapist we spoke with stressed that the underwater treadmill should be used as part of an overall treatment plan rather than its sole focus. For example, a typical surgical rehabilitation schedule at SOL Companion would begin one to two weeks post-operatively and include passive range-of-motion exercises to be performed by the owner three times a day, daily walking from 5 to 10 minutes at a time, and crating to limit movement. A month to six weeks later, the dog would begin two to three sessions a week at the clinic, where he’d undergo hands-on tissue work, hydrotherapy, and movement therapy, while continuing at-home work with the owner.

These rehabilitation centers are also a perfect location for complementary practitioners to offer adjunct services. At SOL Companion, a client can receive acupuncture from veterinarian and certified veterinary acupuncturist Kirsten Williams, or massage and myofascial release work from credentialed therapists. Patterson explains that using several therapeutic techniques usually results in a better outcome than using just one.

“We use a variety of soft-tissue techniques, which include myofascial release and active release technique, to free up any adhesions or tightness that may have occurred, either from the injury or from being immobilized,” she explains. “We may also do some joint mobilization and acupuncture; the latter is good for pain management and mobility. That’s all just to regain normal movement and normal joint movement.”

Those best qualified to work with dogs on the underwater treadmill include physical therapists who have expanded their practices to include dogs, and veterinarians or veterinary technicians who have formal training in animal rehabilitation.

Currently, there’s no such title as an “animal physical therapist,” although some specialized training programs exist. The term “physical therapist” (PT) is reserved for professionals who work with humans (see sidebar below).

While some dogs respond very well, hydrotherapy shouldn’t be viewed as the magic bullet, Patterson warns. As evidence, her center has only one underwater treadmill but is chock-full of other therapeutic equipment, including balance boards, oversized exercise balls, and even a mini-trampoline.

Still, the underwater treadmill work is a promising therapy that could become a new standard of care. And while results so far are strictly anecdotal – no rigorous studies of outcomes have been done – word of mouth has been encouraging. Dr. Sherman believes the treadmills will be available in every major metropolitan area someday. “This is an up-and-coming veterinary specialty,” he says.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “The Benefits of Hydrotherapy For Your Dog”

Click here to view “Happy Hydrotherapy”

C.C. Holland is a freelance writer from Oakland, CA, who enjoys applying what she learns about canine health and behavior to her own mixed-breed dog, Lucky. This is her first article for WDJ.

Acupressure Can Relieve Nausea

[Updated October 19, 2017]

Catherine took a sweeping, cloverleaf turn onto the interstate, and quickly became thankful that she had thought to bring a travel-crate for Hugo, her new nine-week-old Saint Bernard puppy. She was taking Hugo home for the first time, and Hugo’s tummy was not up to the ride – up came his little breakfast. Puppies commonly suffer from motion sickness, but older dogs can have their moments, too.

Those of us who have had the experience of a carsick dog might select a number of other words for the condition, but in Traditional Chinese Medicine regurgitation is considered “rebellious stomach chi.” Stomach chi is the life-force energy that supports the stomach’s ability to function properly. Stomach chi is supposed to flow downward, not upward. If the chi goes in the wrong direction, it is being “rebellious” and that’s not fun for dog or driver.

There are specific acupressure points that you can use before taking your dog in the car to help avoid having your dog experience rebellious stomach chi. By applying pressure to these particular points, you are effectively helping your dog balance the flow of energy throughout his body so that his stomach chi will flow in its natural direction – down.

Acupressure has been used for thousands of years for physical and emotional problems in both animals and humans. These simple techniques can resolve injuries more quickly; support the body before, during, and after surgeries; reduce swelling; minimize pain; help with calming; and improve immune system conditions.

Acupressure is always available and perfectly safe, so you can perform a treatment whenever you suspect that travels with your dog might be a bit bumpy, taxing his stomach chi. Give it a try. This will make for happier trips for both you and your best friend.

Acupressure Treatment for Nausea

We suggest you perform the following motion sickness/nausea treatment within an hour prior to getting into the car. Of course, this treatment can be used for other times when nausea or stomach upsets are causing your dog discomfort. An acupressure treatment is a comforting and healing experience for you and your animal. Start by finding a quiet, calm location, where your dog feels at ease. Breathe evenly and slowly while thinking about how you want your dog to feel. Once you have formulated your intention for the treatment, you are ready to begin.

Acupresure “Opening”

Gently place one hand on his shoulder; this hand serves as your “anchor” hand. Place the heel of your other hand at the top of his neck just to the side of his spine and stroke down his neck. Continue by smoothly stroking over his body down to his hindquarters, staying to the side his spine.

Continue to stroke down his leg following the bladder meridian (see diagram) to the outside digit. Do this same stroking with the heel of your hand three times on each side of your dog. The opening prepares your dog for intentional touch.

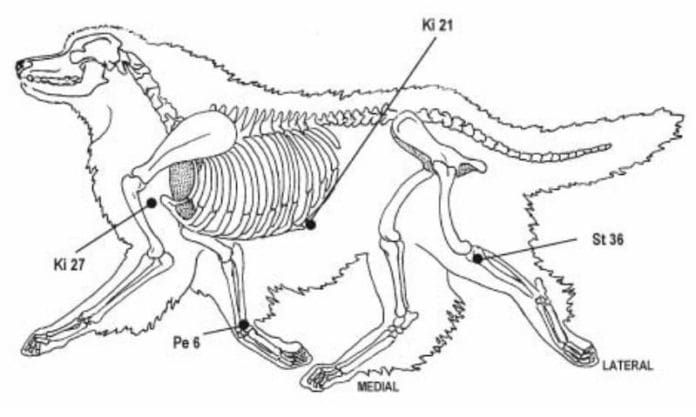

Point Work for Dogs’ Motion Sickness

For the point work phase of this treatment, follow the Motion Sickness/ Nausea Chart below. Start by resting one hand comfortably on your animal. Use your other hand to perform the actual point work. Hold a specific acupressure point for about 30 seconds up to one minute. Use one of the following point work techniques:

Direct Thumb Technique: Gently place the tip of your thumb directly on the acupressure point at a 90-degree angle adding a little pressure.

Two-Finger Technique: Put your middle finger on top of your index finger and then place your index finger at a 90-degree angle gently, but with intentional firmness, directly on the acupressure point.

Use whichever technique is most comfortable for you and your dog. The two-finger technique seems to be particularly good for smaller dogs and the thumb technique for larger dogs.

| POINT | TRADITIONAL NAME | ACTION |

| Pe 6 | Inner Gate | “Master point” for chest and cranial abdomen. Powerful anxiety reducer, balances the internal organs. Relieves nausea. |

| Ki 21 | Hidden Gate | Relieves nausea and counterflow of chi. (Located a half-inch from the dog’s midline.) |

| Ki 27 | Shu Mansion | Harmonizes the stomach and lowers rebellious chi. (Located between the sternum and the first rib.) |

| St 36 | Leg 3 Miles | Harmonizes the stomach, supports the correct flow of chi, and calms the spirit. |

Watch your dog’s reaction to the point work. Healthy energy releases include yawning, deep breathing, sighing, muscle twitches, and softening of the eyes. If your dog exhibits a pain reaction to a particular point, work the acupoint in front of the reactive point or behind it. Try that point again at a later session.

Acupressure “Closing”

To complete the acupressure session, repeat the stroking procedure described in the “Opening” phase of the treatment. With the heel of your hand, tracing the bladder meridian as shown above, stroke down your animal’s body, starting at the top of the neck, just off the midline.

Repeat the stroking three times on each side of his body just the way you did in the Opening. This procedure reconnects the flow of energy and establishes the new cellular memory.

OVERVIEW

1. An hour prior to getting in your car with your dog, find a quiet, calm place and perform the acupressure treatment described here.

2. Try to keep your car trips short the first few times you try the acupressure.

3. If your dog begins looking uncomfortable on the road, find a place to pull over and rest for a while. Use the acupressure techniques for a few minutes before continuing.

Nancy Zidonis and Amy Snow are the authors of, The Well-Connected Dog: A Guide to Canine Acupressure. They own Tallgrass Publishers, which offers meridian charts for dogs and other companion animals. They also provide training courses worldwide.

Download the Full February 2003 Issue

Join Whole Dog Journal

Already a member?

Click Here to Sign In | Forgot your password? | Activate Web AccessNew to Positive Dog Training?

Please bear with me for a moment while I brag on Dubhy, our two-year-old Scottish Terrier. From the time we found him as a stray puppy at age six months, we have trained him using methods and management tools consistent with my positive training philosophies. He is the first of our canine family members to be trained completely with modern, non-coercive methods.

Last weekend, we put up a brand-new set of agility equipment in our backyard. As my husband was tightening the last bolt, I dashed into the house to get Dubhy, who has never seen an agility course. To my delight – but not surprise – he happily and willingly traversed even the most daunting of the obstacles on the first go-round. Well, the closed tunnel gave him pause for a moment. When he couldn’t see his way through the collapsed chute, he jumped on top of the barrel instead, and perched there happily, sending me a cheerful “Is this what you wanted?” query from his sparkling eyes. When I invited him off the barrel and opened the chute to show him the way through, that obstacle, too, was quickly conquered.

I’ve had other dogs who were just as smart as Dubhy, but until the feisty Scottie came along, I had not yet owned a dog that I trained completely without compulsion: No “ear pinches,” yanks on the collar, knees in the chest, stepped-on toes, or any other physical “corrections” whatsoever. And, oh! What a difference it can make.

Don’t get me wrong; I have not used coercive training techniques for more than 12 years. I was totally and completely converted to “positive-only” training techniques following a moral, professional crisis with another one of my dogs a dozen years ago. Since then, I’ve used only “dog-friendly” training methods with thousands of dogs and seen ample proof that these effective methods encourage and foster a strong, trusting bond between dogs and their owners.

However, until Dubhy, I had never so clearly seen the difference between a “crossover” dog – one who was initially trained with force-based methods and then switched to positive-only training – and a dog who had never experienced scary, hurtful, or force-based training. They are, as the saying goes, completely different animals.

Crossover consequences

Take, for example, Josie, the canine love of my life. The Terrier mix was a joyful and willing worker, and we accomplished a lot together, including titles in competitive obedience and Rally. Josie was also my first “crossover” dog; until she was three years old, I had trained her with conventional force-based methods. Josie prompted my conversion one day when she hid under the deck and unhappily refused to come out when she saw me getting out a set of retrieving dumbbells in preparation for a training session. (I had been working to teach her to retrieve using a conventional coercive training method, the ear-pinch.)

After this incident, I took a two-year time-out from training to learn about modern, positive methods that are grounded in the science of behavior and learning. Only then did I begin training Josie again. This time, I used only dog-friendly training methods, and she responded beautifully. Our accomplishments continued apace.

But throughout the rest of her life, Josie’s response to new training situations or requests was very different from Dubhy’s eager and creative volunteerism. The best way I can describe this is that when faced with something new, she waited to be shown what to do – as do many crossover dogs. My guess is that her fear or anxiety about doing the wrong thing was stronger than any impulse she might have had to try to guess what I wanted – even though, for the last 12 years of her life, she was never punished for doing the wrong thing.

In other words, faced with a unique training request, crossover dogs like Josie tend to do nothing, or offer a safe behavior that they already know.

Why positive methods work

In contrast, Dubhy and other dogs who were encouraged since infancy to “offer” novel behaviors in response to new training requests, joyfully go to work trying to solve the puzzle. The modern methods of training teach, foster, and capitalize on this initiative; the dog’s volunteerism is what makes it works so well.

In positive training, the goal is to help the dog do the right thing and then reward him for it, rather than punishing him for doing the wrong thing. If he makes a mistake, the behavior is ignored, or excused with an “Oops, try again!” to encourage the dog to do something else. Using “Oops!” as a “no-reward marker” teaches the dog that the behavior he just offered didn’t earn a reward, but another one will. So he tries again, and learns to keep trying until he gets it right, without fear of punishment.