[Updated February 7, 2018]

Standing transfixed in my veterinarian’s exam room, I stared at my dog’s x-rays, trying to focus on what the vet was saying. My mind seemed to have gone into some kind of vapor lock after hearing the words “severe hip dysplasia, both sides.”

I don’t know what I had expected. I was there because I knew something was wrong, but I hadn’t thought the news would be this bad. My 6½-year-old Spaniel mix, Sandy Mae, normally a confident and experienced agility competitor, had been refusing 22-inch jumps, and sometimes even 16-inch jumps. She also seemed tired, walking slower than her normal sprightly pace on our daily walks. At first I thought it might be because she was about 5 pounds over her optimal weight of 28 pounds. But it was the telltale bunny-hopping of a dog with hip problems that sent me to the veterinarian’s office.

Surprising both myself and my vet, tears streamed down my face when I heard the diagnosis. I knew what it meant because my 14-year-old mixed breed, Chelsea, had suffered from hip dysplasia since age nine and, despite an aggressive regimen of neutraceuticals (e.g., glucosamine, chondroitin, MSM), had great difficulty getting up and down. Sandy, who wasn’t even seven, had already been on neutraceuticals for several months. I couldn’t bear the thought of her going through so many years of similar discomfort.

After getting the opinions of three orthopedic specialists – and engaging in countless discussions with other owners of dysplastic dogs – I made a very difficult decision. I was going to have Sandy undergo a surgery called bilateral femoral head osteotomy (FHO). I knew that I faced challenging post-operative care and rehabilitation, but I assumed that I would do the best I could when the time came.

What I didn’t realize at the time was how much I had already done – before she was even diagnosed.

Preparing for Hip Dysplasia Before it Happens

Sandy came into my life at about 10 months of age. She was a neglected dog whose owners kept talking about getting rid of her. She was just too much for them to handle; she often found a way to get out of the backyard and then amused herself by chasing cars and jumping on the neighbors. Through a series of events coordinated by a friend who lived next door to the little rascal, I agreed to foster her. Without asking for my approval, Sandy and my then two-year-old dog, Buster, fell in love, becoming inseparable in just a few days. Voila! Another dog in the family.

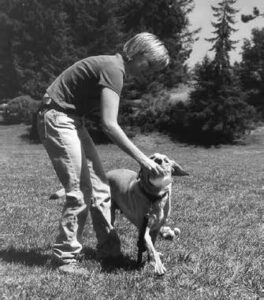

Sandy’s personality from the time I got her was feisty, happy, and energetic. Still, taking no chances, I focused on intense socialization since she had had very little exposure to the world outside her backyard. I took her on errands and walked her through shopping malls. I dropped her off at friends’ homes so that she would be accustomed to being away from me. I took her to the dog park where one of her favorite playmates was an Akita who would pin her down in mock battle.

In 1996, I was introduced to clicker training at the Association of Pet Dog Trainers’ annual conference in Phoenix, Arizona. I watched Karen Pryor and Gary Wilkes demonstrate how to “shape” behaviors – anything from sit and down to “targeting” with a target stick. I bought a target stick and clicker at the conference and brought them home to try with my own dogs. Over the years I used clicker training to teach Sandy a variety of behaviors: sit, down, stay, come, spin, wave, dance, back up, bow, 101 Things to do With Anything in the Environment, and on and on. She became my star demonstration dog in my classes, as well as at community events.

I also introduced Sandy to agility, which I had been doing with Buster for building his confidence. When I was practicing with Buster, Sandy would sit in her pen, bright and alert, watching us run around the course. On her first try at the agility obstacles, she took to the sport like a fish to water. In December1999, Sandy achieved her Master Agility Dog Title from USDAA, our chosen agility venue.

Hip Dysplasia Surgery for Dogs

Perhaps if Sandy had led a less-active life, I would not have considered something as invasive as bilateral FHO. This surgical procedure involves the removal of the femoral head (the ball). To help the healing process, the dog must walk short distances soon after surgery to strengthen the muscles, ligaments, and tendons in that area, all of which work to form a false joint to take the place of the old ball and socket.

If Sandy were a couch potato, I might not have chosen surgery and the difficult rehabilitation that would follow. Instead, I might have chosen to continue with the neutraceuticals, restrict jumping on and off furniture, and give her pain medication when necessary. But Sandy had always been an active dog, and restricting her activities would have been too hard on both of us.

Also, Sandy’s small size (28-33 pounds) made her a good candidate for FHO; the procedure is less successful for larger dogs. The price, too, was more affordable for me: The price I was quoted was $2,200 total (and actually, I paid less, thanks to a very generous professional discount from the veterinarian) as opposed to $4,000-$5,000 per hip for total hip replacement.

Conversations with an agility friend and competitor, Elina Heine, of Oxnard, California, helped me clinch the treatment decision. Heine’s Border Collie/Australian Shepherd mix, Turbo, had recently undergone bilateral FHO surgery and seemed to be recovering with great success. I especially respected Heine’s opinion because she is a registered physical therapist. In fact, she had designed a rehabilitation plan for Turbo that she generously offered to share with me.

Planning for the Symptoms of Hip Dysplasia

When Sandy began showing symptoms in the fall of 2000, I pulled her from agility trials and greatly reduced her agility play. After I decided on FHO, I embarked on a plan to prepare her for surgery:

• I put her on buffered aspirin so that she could tolerate more activity.

• I reintroduced agility as a regular form of exercise in order to maintain muscle mass and strength. I let her jump only 12-inch jumps, go through tunnels, and do an occasional dogwalk and weave poles, letting her “tell” me when she was tired by slowing down or going around (instead of over) obstacles.

• I maintained her daily off-leash exercise outings, which amounted to a one- or two-mile outing at whatever pace she chose.

• I switched her to a reducing diet in order to get her weight down, assuming that the less extra weight she was carrying after surgery, the better. (She dropped four pounds before surgery!)

• Using clicker-training methods, I trained her to walk wearing a sling under her belly, with me holding up her rear end. This exercise included walking up and down three stairs on the back porch, using her front legs only.

• I simulated range-of-motion exercises that I planned on doing during rehabilitation, hoping that she would become accustomed to these activities so that they wouldn’t be completely foreign to her later.

Bilateral Femoral Head Osteotomy Surgery and Week One of Recovery

Sandy’s surgery was scheduled for January 17, 2001. I had been dreading it for weeks and was relieved to finally have it over and to hear from the surgeon that all had gone well. Sandy came home after only two days in the hospital.

Those first days after surgery were extremely difficult. Even though the veterinarian had given me medication to give Sandy for pain relief, Sandy experienced a lot of pain when I moved her to get up to go outside. I would carry her outside and then put the sling under her and support her weight while she figured out how to urinate and defecate without really squatting. However, she would take two or three steps without the sling, and by the fifth day after coming home was taking several wobbly steps to move from one resting place to another.

That first week was tough, though. She didn’t want to get up to go outside because it hurt when I reached under her to pick her up. I knew she could get up and toddle around on her own because she would change positions in bed, and she was taking more steps once she was up. That’s when I first decided that I needed to draw on the strength of our relationship to encourage her to get up on her own.

On the fourth morning after surgery, I had some treats ready. I stepped away from her bed and said in a perky voice, “Sandy, come!” She looked at me as if I had lost my mind. I simply repeated myself and backed toward the door. She shoved her front feet under her chest and sat up. Click! Treat! The look in her eyes changed when she heard that click. Oh, it’s the clicker game! I can do that!

I then said, “C’mon. We’re goin’.” She wobbled to her feet. Click! Treat! She stepped out of the bed. Click! Treat! And we made our way down the hallway into the living room, where I picked her up and carried her the rest of the way. From that point forward, she got up in the morning by herself and walked most of the way outside. When she was tired, she would stop and look up at me, and I would carry her.

On the same day that she got up on her own, I took her to our usual exercise field and put her on a blanket where she could watch the other dogs run around. She actually got up and walked about 100 feet. I was by her side, calmly encouraging her every step of the way.

Hip Dysplasia Recovery Weeks Two and Three

The second and third weeks after surgery were a time of longer and longer walks. Sandy’s strength and endurance were both improving. I launched a rehab program based on my discussion with Elina that included:

• walking (gradual progression of distance and speed)

• passive range-of-motion exercises for her hips

• soft tissue massage for hips, back, and front end

• aquatherapy

How Emotional Bonds Help Heal

It was during the more intensive period of rehab work that I discovered how my relationship with Sandy impacted her recovery. I believe that there were five important elements that contributed to an extremely fast recovery:

1) The trust that Sandy had in me from the handling exercises I had done with her since she was a puppy (e.g., fake examinations, restraint exercises, as well as interventions on her behalf in removing foxtails and burs helped her trust me when she experienced pain or when I was lowering her into a Jacuzzi).

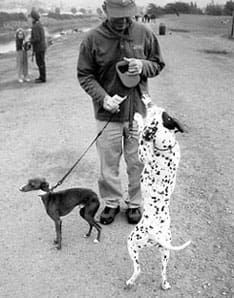

2) Her high level of socialization that meant she had a world filled with doggy and human friends who not only motivated her to rejoin them, but also created a confident, psychologically healthy dog.

3) An active lifestyle, including living with other active dogs, helped to set the stage for returning to that lifestyle.

4) Clicker training, which focuses so much on teaching a dog to learn how to learn and building his or her confidence to offer new behaviors, made it easy for Sandy to learn new things such as walking and going up stairs with a sling under her belly, swimming in a jacuzzi, etc.

5) Agility training meant that Sandy was in good physical condition, and the teamwork we enjoyed helped us to retrain her body as quickly as possible to the functioning level she remembered from her past.

Milestones of Improvement After Hip Dysplasia Surgery

These elements were integrated into a rehab program that resulted in an amazing recovery, as evidenced by these milestones:

Day #7: Trotted (albeit wobbly) to greet a good friend. The power of a dog’s friendships is incredible.

Day #8: Walked up and down the back-porch steps by herself. At first, I clicked and treated her for these behaviors, encouraging her to try to figure out how to place her feet carefully and not fall over.

Day #15: Rolled on her back in the grass at a park, flipping hips back and forth sideways. The delight of new grass in a new location unleashes the sillies.

Day #18: Responded to clicker training to back up on cue, relearning to move and place each foot – a trick she did nimbly before surgery. Waving on cue, another trick she knew previous to surgery, helped her use her back muscles to help support herself while she lifted a front foot into a wave. “Spin,” another old trick, helped her use her legs independently, as well as stretch the muscles along her ribs and thighs.

Day #20: Engaged in power “aquawalks” in a deep tub, pushing with her rear legs against the water. This was accomplished by doing recall relays between two people at opposite ends of the tub, each with a bag of chicken!

Day #21: Played tug-of-war with one of my other dogs, and won! She had learned how to use her front end for stability and strength, and her rear end for balance only.

Day #40: Jumped up on the couch for cuddling. The importance of touch was powerful motivation for Sandy.

Day #45: Slowly navigated a set of four weave poles. Agility is something she loves. When I said, “Weave!” she started right in, but almost fell over because her rear end had become weak. She had to relearn how the legs and muscles needed to act to accomplish an old trick.

Day #50: Performed (slowly) a full set of 12 weave poles; offered a “stretch” (bow) during a clicker training session with other dogs. Peer pressure!

Day #65: Jumped into the back of a friend’s hatchback, something she’d been contemplating for days because of the snacks this friend always has in his car.

The Power of Strong Relationships

Would Sandy have recovered without agility and her tricks? Yes, I’m sure she would have – eventually. However, her recovery rate impressed many people who have had experience with FHO recoveries. Sandy entered her first agility trial in June 2001, just six months after surgery.

Recovery from an invasive procedure such as FHO is challenging. My experience with Sandy has convinced me more than ever that the best antidotes to the health challenges many of our dogs will confront throughout their lives include a strong relationship built on trust, positive reinforcement training, and structured activities such as agility. You can bet I’ll be embarking on a similar relationship-building path with my new pup, Kiwi. Sandy Mae is already showing him the ropes, tail high as she clears those jumps and runs circles around him.

Another Hip Dysplasia Operation Success Story

While I definitely customized Sandy’s rehabilitation plan to suit her personality, I was lucky to be able to draw heavily upon the experiences of my friend Elina Heine, of Oxnard, California, whose Border Collie/Australian Shepherd mix, Turbo, had weathered the same surgery with great success. I called Heine several times during Sandy’s recuperation, and asked how Turbo was doing. Heine, a registered physical therapist, used her professional knowledge to design an optimum therapeutic program for her dog, and also drew on the knowledge of her holistic veterinarian and complementary therapies. In addition, both of us credit our deep relationship with our dogs – fostered through positive training and agility work – as being a critical component of our dogs’ successful recoveries.

Unlike Sandy, who was 6½ years old when diagnosed with hip dysplasia, Turbo was only 18 months old when he was diagnosed with the same condition. Turbo loved competing in beginning agility, but Heine soon found that he would be slightly lame after an agility show. “Then he started showing progressive stiffness in the mornings and after walks, and he developed a ‘hitch’ in his gait.”

Turbo’s initial examination and diagnosis was conducted by Heine’s holistic veterinarian. He was amazed at the speed at which Turbo’s symptoms came on and the severity of the dysplasia, and was not sure that the dog would ever be a competitive dog again. Heine immediately started Turbo on a physical therapy regimen and supplements (including glucosamine and chondroitin) that could benefit his joints. The veterinarian also referred Heine to a veterinary orthopedic surgeon, who gave her three options: 1) restrict Turbo’s activity and keep him on neutraceuticals and pain medication; 2) total hip replacement; or 3) bilateral femoral head osteotomy (FHO).

“I sat on the diagnosis for about six weeks and in that time, followed the guidelines of the orthopedist and my holistic vet,” says Heine. “I significantly limited Turbo’s exercise, but this did not slow the progression of the disease. Plus, this regimen began driving him crazy. He developed many bad behaviors, such as peeing on the couch, getting nippy with the other dogs, and he had a much shorter attention span.

“The fact that his stiffness and pain symptoms were getting worse, and we had significantly limited his walking (no running, no agility, limited ball-fetching with slow, low tosses), led me to the decision to do the surgery.”

Though at 47 pounds Turbo is on the upper end of the weight range for which many orthopedists recommend FHO, Heine preferred the option of FHO because of the lower cost (compared to total hip replacement) and the type of rehabilitation that FHO surgery calls for. “Rehab for a total hip replacement includes weeks of kenneling and a gradual increase in activity – time spent waiting for the hip joint capsule to heal and strenthen,” describes Heine. “The FHO rehab is much more active. The dog has to walk to start the development of the callus on the femoral neck (the remaining bone) and to make sure the ligaments and muscles heal, allowing appropriate motion at the hips.

“I knew my dog, and I knew he had been going through hell for the six weeks of ‘taking it easy.’ Kenneling would have added even more to his behavior problems. It was difficult to decide the best route to take, but looking back, it was the best one for us, both then and now,” says Heine.

Postsurgical Work

Unlike me, Heine did not utilize swimming as part of Turbo’s rehabilitation. “Swimming is a great therapy, but I did not include it in my rehab plan because Turbo has an extreme dislike for water,” says Heine. “More importantly, I felt the weightbearing activities were more important for the development of the callus and the new hip joint. The walking progression was most beneficial for Turbo. Also, the range-of-motion work with his hips assured that the joint would heal with functional motion and was very important for the first three months – until he was no longer showing stiffness in the mornings and evenings.”

Heine’s holistic veterinarian was kept apprised of Turbo’s progression, and Heine followed his recommendations regarding supplements. “We used amino acid supplements (creatine and L-carnatine) to assist in muscle mass development, antioxidants for assistance in Turbo’s general holistic regimen, and some homeopathic remedies early on to assist in healing. We have also used chiropractic treatment a couple of times.”

It All Comes Back to Relationships

Like me, Heine found that the deep and trusting relationship that she and her dog had established through mutually enjoyable pursuits (agility) played a big part in his successful recovery. “Agility was a great help for several reasons,” she says. “First was the conditioning and strength the dog had prior to the surgery. His rear legs had atrophied a lot in the two months prior to surgery, but his front end and back were very strong.

“Second, the trust and teamwork we had developed with the sport allowed both of us to have a rehab plan that he knew and understood. For example, I set up a row of jumps in the backyard – without jump poles – for him to walk through. It was something he recognized and could do. The same could be used with a ‘go out’ or any other skill that you have trained with the dog. The pain and discomfort is there, but the dog is doing an activity that he knows and loves. Turbo was ecstatic to hobble through the chute of three jumps without bars the first time – and what a treat he got at the end!

“Third, returning to agility, which my dog loves even more than I do, helped motivate him to develop the strength and endurance he had prior to surgery,” says Heine.

Terry Long is a professional dog trainer in Long Beach, California, where she provides manners, tricks, and agility training, as well as behavior modification consultation. She is the managing editor of the Association of Pet Dog Trainers’ APDT Newsletter.