Download The Full February 2005 Issue PDF

Successfully Adding a New Dog to Your Pack

The decision to add a new dog to the pack shouldn’t be taken lightly. I counsel prospective owners of new dogs to be clear about their needs and preferences rather than making spur-of-the-moment rash decisions, because their success at integrating a new dog into an existing “pack” so often depends on their ability to make informed decisions. These choices include what kind of dog to adopt, how to prepare their home to accommodate the new dog, how to introduce the new dog to the existing household members, and how to incorporate her into family routines.

Bringing a new dog into the family can be fraught with unexpected developments, no matter how experienced a dog owner is, how well her home is prepared, and how good-natured the dogs are that she already owns. I’ve incorporated a new dog into my family dozens of times in my lifetime, counseled hundreds of clients about how to do it, and written a number of articles about it for this magazine (see “New Puppy Survival Guide,” this issue), and I still am surprised by the issues that can arise when a new dog comes home. However, with preparation, flexibility, and dedication to principles of positive training and behavior management, most dog owners can get through the adjustment period with peace in the pack.

Open your heart

I recently had the chance to practice what I preach when the loss of Dusty, our valiant Pomeranian, left a vacant spot in our pack last spring. Dusty had been my almost constant companion for close to 15 years, and though it’s been nearly five months, the pain of his passing is still close to the surface. I often tear up as I think of his dear little fox face and boundless good cheer.

One of the things I do to help ease the overwhelming hurt of losing a close companion is to remind myself that it also means there’s room in our family for another. Without actively looking, I know that a new furry face will one day draw my attention and grab my heart, as surely as if I had hung out a “Vacancy” sign. So it was early this summer, when I was doing behavioral assessments at the Humane Society of Washington County, where my husband, Paul, serves as the executive director.

As is my custom on the day that I do assessments, I made a quick pass through the kennels before picking up paperwork for the day’s list of dogs. In one ward, a brindle-and-white pixie with huge stand-up ears, a low-rider body, and an excessively generous tail with one decisive curl in the middle captured my attention. A Corgi pup? I glanced at her kennel card. Sure enough – a five-month-old Corgi, and a Cardigan at that. (Pembrokes are the Corgis with short tails, Cardigans have long tails.)

I have long been enchanted by Corgis, and occasionally fancied adding one to the family some day. Perhaps this was the time?

Dashing back to the Operations Center, I placed the Corgi’s paperwork on the top of the stack. I was determined not to make too rash a decision – we would at least evaluate her before I lost my heart.

Develop a list of desired traits

In my case, I knew that I was looking for a small- to medium-sized dog, with a preference for a short-coated female. With three other dogs in our home already, a smaller dog would fit better than a larger one, and with one neutered male dog at home who could sometimes be aggressive with other male dogs, estrogen seemed like a wiser choice than testosterone. I lean toward the herding and working breeds; I like their genetically programmed work ethic. As much as I adore our most recent addition to our canine family (Dubhy, the Scottie), I really wanted a dog who was more hard-wired to work closely with people, and one who would (I hope) grow up to be highly social with people and other dogs. And I like to adopt dogs who are five to 10 months old – past the worst of the puppy stuff, but still young enough to be programmable. With that checklist in mind, the young Corgi seemed to fit the bill – so far.

The results of her assessment were mixed. On the positive side:

• She was highly social; she couldn’t get enough of humans – so much so that I was confident she’d be a good off-leash hiking partner on our farm.

• She was very bright and trainable; she quickly learned to offer sits during the training portion of the process.

• She was resilient and nonassertive, responded well to the startle test, and offered appeasement signals rather than aggression during the “stranger danger” test.

In the negative column:

• She did pretty persistent tail-chasing during the evaluation. Uh-oh … a dog with obsessive-compulsive behaviors at the tender age of five months. That’s a red flag!

• She never stopped moving. This little girl clearly is more energetic than the average dog.

• She was very vocal – and her voice was very shrill. Despite my intent to make an unemotional clear-headed decision, I was smitten. I carried her into Paul’s office and set her on the floor. He looked at her, glanced at my face, smiled, and said, “When are we doing the paperwork?”

We weren’t quite that foolhardy. We were confident that Tucker and Katie could manage to live with her, but knowing that Dubhy can be selective about his canine friends, we arranged to bring him in to meet her. If he gave the nod of approval, we would adopt. One week later, Lucy (short for “Footloose and Fancy Free”) joined the Miller family.

As we set about assimilating Lucy into our social group, I was humbled by the reminder of how challenging it really can be to adopt a young dog in sore need of good manners training. There’s nothing like having to use the suggestions and instructions yourself that you routinely offer your clients to give you a much better appreciation for how well they sometimes work – and sometimes don’t.

Modify to the individual

There are exceptions to every rule. No matter how well a technique may work with most dogs, there are some dogs who require their owners to stay flexible and be willing to tailor the technique to their needs.

Case in point: I frequently use tethering in my training center, and often offer it as a solution for dogs whose behaviors need to be under better management and control in the home. Such a simple, elegant solution – what could possibly go wrong? I was about to find out.

Lucy’s initial introduction to the rest of the pack was easy. We let them meet in the backyard, where the open space was more conducive to successful relationships. As we had expected, she offered appropriate appeasement behaviors to Katie “the Kelpie Queen” and was permitted to exist. She and Dubhy had already met and seemed to remember each other. She wriggled her way up to Tucker, the Cattle Dog-mix, and he accepted her annoying puppy presence easily.

Indoors, however, we discovered that at the tender age of five months she was already a dedicated cat-chaser. Perfect time for a tether, I thought – and quickly discovered that she still charged the cats when they entered the room, only to hit the end of the tether at full speed, moving a very heavy coffee table several feet, and risking injury to her neck. Tethered in my office, she promptly began guarding the entire space with ear-splitting barks and ugly faces.

She also gave shrill voice any time she was left tethered by herself in a room for even a brief moment. Leaving her a stuffed Kong or other valuable chew toy simply elicited serious resource-guarding behavior toward the other dogs. Too much tether time also triggered the obsessive/compulsive tail- chasing that worried me during her evaluation. Life quickly became very stressful. I experienced more than a few “What have I done?” moments.

Ultimately – as in four months later! – I finally succeeded in getting Lucy to lie by my chair rather than chase the cats. To accomplish this, I had to use less tethering and more counter-conditioning and desensitization (“Cats make really good treats happen!”). Our cats can again tread softly into the living room to spend the evening on our laps without fear of a Corgi attack.

Appreciate the successes

On the bright side, Lucy was everything I had hoped for in other areas. Our first day home, we went for a long hike with the rest of the pack. Halfway through, I took a deep breath, crossed my fingers, and unclipped her leash. As I had hoped, she stayed with the other dogs, and came flying back when I called her.

I smiled to see her bounding through hayfields, leaping after the butterflies that scattered in her path. She quickly learned to paddle in the pond and stick her head down groundhog holes with the other dogs. She will even happily traipse alongside my horse as we ride the trails – an even better source of exercise than hikes with the pack!

The daily exercise did wonders for her tail- chasing, which vanished in less than a week, returned when we had to restrict her activity following spay surgery, and vanished again as soon as she could run in the fields.

Feeding time was another challenge. Lucy’s propensity to resource-guard gave rise to a few dramatic meals, but the other dogs solved this one for me. Dubhy, a skilled resource-guarder in his own right, quickly set her straight about intruding on his dinner, and Lucy decided that she was best off with her nose in her own bowl. I knew that the commonly offered solution of feeding in crates wouldn’t work for her. She already guarded her crate space from the other dogs.

Adding food to the crate equation would have been a disaster!

Lucy came with some other behavior challenges. When taking treats, her hard mouth – “sharky” – actually drew blood from my fingers during our first few weeks together. This time, the advice I usually give worked, although it took longer than I expected, and it was even more difficult in the presence of the other dogs.

I began offering treats to her enclosed in my fist. If she bit hard enough to hurt, I said “Ouch!” and kept my fist closed until her mouth softened. When she was gentle, I opened my hand and fed her the treat. It was a delight to feel her begin to deliberately soften her bite, even in the presence of the other dogs or with a very high value reward. Now, five months later, I realize I haven’t “Ouched” for several weeks. Progress does happen!

Think outside the box

When a tried-and-true approach doesn’t work, don’t persist in hammering that square peg into a round hole. Instead, be creative and try to adapt your favored approach to your dog’s situation.

Lucy decided early on that she didn’t like going out the back door to the fenced yard. She quickly learned the back door means she’ll be out in the backyard for a while with the other dogs. She much prefers the side door, which means either hikes in the field, stall-cleaning time, or off to the training center – all of which she adores.

All my first responses to the problem only made it worse. The door is at the end of a narrow hallway, so calling her or walking down the hall and turning to face her, only made her less interested in going out. I tried continuing through the door onto the back deck myself, with no luck. Luring with treats worked twice; she got wise to that very quickly. Even though she is pack-oriented, she never fell for the trick of chasing the rest of the dogs enthusiastically out the door. Reaching for her collar to lead her out made her wary of my hands moving toward her.

We finally found two strategies that worked, and continue to use them both in hopes of getting her happy about going out the door rather than just tolerating it:

• Fetch! Lucy loves retrieving, so I have made it a point to frequently pair going out the back door with an energy-eating round of fetch the doggie disc.

• Leash! While Lucy quickly learned to avoid my reaching for her collar, she is happy to munch a treat from one hand while I slide a slip lead over her head with the other. Once leashed, she follows willingly out the back door and stands while I feed another treat and slip the leash off her head.

Patience pays off

I counsel owners not to adopt a second dog until the first is trained, because the difficulties encountered when trying to train two at once are more than most people can successfully take on. It’s challenging enough to train one dog – and it’s even harder to get much done if two or more dogs are out of control at the same time.

Although my other dogs are reasonably well trained, I made it a point to work with Lucy separately, at least at first, until she knew a new behavior, before I asked her to do it in the company of her canine companions. I had the luxury of a separate training center to work in, but even if I hadn’t, I could have worked with Lucy outside while the others were in, or vice versa. I could have trained Lucy in one room while the other dogs were shut in another part of the house, or crated them with yummy, food-stuffed Kongs so they didn’t feel deprived while I focused my attentions on the new kid. A dog can even learn to sit quietly in his own spot while watching another dog in training, knowing that the reward of his own turn is coming soon.

Lucy is nowhere near perfect. While she heels beautifully in the training center, she’ll still pull on leash outside unless she’s wearing a front-clip no-pull harness, preferably the K9 Freedom Harness (available from waynehightower.com). I found myself losing my patience with her pulling until I started using the harness. Now we both have more fun when she has to walk on a leash. We both prefer the off-leash hikes, of course.

She still jumps up, but not nearly as much as she did at first. Our persistence in ignoring the jumping up and rewarding polite greetings is paying off. She still has a shrill voice, but doesn’t use it quite as often as she used to. I must constantly remind myself – and Paul – to redirect her behavior when she’s barking, rather than falling into the natural trap of yelling at her to be quiet.

She now spends a lot of time lying quietly on my office floor instead of traumatizing kitties, hasn’t chased her tail in months, and chews only on toys provided for that purpose. She hasn’t had an accident in the house for several weeks now, and although she and Katie have small arguments almost daily, I don’t usually have to intervene.

Last night, as Paul and I sat watching TV, I looked up at all the dogs sleeping quietly on their beds, and realized that it’s been quite some time since I’ve had one of those “What have we done?!” moments. She has become a full-fledged member of the pack. She will never be Dusty, but she is Lucy, and that’s all she needs to be to stake her own claim to my heart. I hope your next adoption goes as well.

Also With This Article

“Adding a New Dog to a Multi-Dog Household – Plan Ahead!”

“New Dogs Do’s and Dont’s”

-Pat Miller, CPDT, is WDJ’s Training Editor. She is also author of The Power of Positive Dog Training, and Positive Perspectives: Love Your Dog, Train Your Dog.

Dog Bloat: Causes, Signs, and Symptoms

BLOAT IN DOGS: OVERVIEW

1. If your dog is a breed at high risk for bloating, discuss with your vet the merits of a prophylactic gastropexy at the time of neutering.

2. Familiarize yourself and your dog with the emergency veterinary services in your area, or anywhere you’ll be traveling with your dog. You never know when you’ll need to rush your bloating dog to the animal hospital.

3. Feed your dog several smaller meals daily rather than one or two bigger meals to reduce your dog’s risk of gastric dilatation.

4. Consider feeding your dog a home-prepared diet; while there have not been studies that support the assertion, many dog owners who make their dogs’ food swear that it prevents GDV.

Imagine seeing your dog exhibit some strange symptoms, rushing him to the vet within minutes, only to have the vet proclaim his case to be hopeless and recommend euthanasia. For too many pet parents, that’s the story of dog bloat, an acute medical condition characterized by a rapid accumulation of gas in the stomach.

In fact, that was exactly the case with Remo, a Great Dane owned by Sharon Hansen of Tucson, Arizona. “He was at the vet’s in under seven minutes,” says Hansen, in describing how quickly she was able to respond to Remo’s symptoms. He had just arisen from an unremarkable, hour-long nap, so Hansen was stunned to see Remo displaying some of the classic symptoms of dog bloat, including restlessness, distended belly, and unproductive vomiting.

Despite Hansen’s quick action, Remo’s situation rapidly became critical. Radiographs showed that his stomach had twisted 180 degrees. Remo was in great pain and the vet felt the damage was irreversible. Hansen made the difficult decision to have Remo euthanized at that time.

Canine bloat, or more technically, gastric dilatation and volvulus (GDV), is a top killer of dogs, especially of deep-chested giant and large breeds, such as Great Danes and Standard Poodles. A study published in Veterinary Surgery in 1996 estimated that 40,000 to 60,000 dogs in the United States are affected with GDV each year with a mortality rate of up to 33 percent.

Gas accumulation alone is known as dog bloat, or dilatation. The accumulation of gas sometimes causes the stomach to rotate or twist on its axis; this is referred to as torsion or volvulus. Bloat can occur on its own, or as a precursor to torsion. In this article, to simplify the terms, bloat and GDV are used interchangeably.

Both conditions can be life-threatening, although it often takes longer for a straightforward gastric dilatation without volvulus to become critical. “Bloats without torsion can last for minutes to hours, even days in low-level chronic situations, without it becoming life-threatening. But with torsion, the dog can progress to shock rapidly, even within minutes,” explains Alicia Faggella DVM, DACVECC, a board-certified specialist in veterinary emergency and critical care.

“A dog can go into shock from bloat because the stomach expands, putting pressure on several large arteries and veins. Blood does not get through the body as quickly as it should,” continues Dr. Faggella. In addition, the blood supply gets cut off to the stomach, which can cause tissue to die, while toxic products build up.

While some less acute cases of dog bloat may resolve themselves, it often takes an experienced veterinarian to know just how serious the problem may be, and whether surgical intervention is required to save the dog’s life.

Symptoms of Bloat in Dogs

– Unproductive vomiting

– Apparent distress

– Distended abdomen, which may or may not be visible

– Restlessness

– Excessive salivation/drooling

– Panting

– The dog’s stomach is hard or feels taut to the touch, like a drum

– Pacing

– Repeated turning to look at flank/abdomen

– Owner feels like something just isn’t right!

Dog Bloat is Frighteningly Deadly

Various studies have estimated the mortality rate for dogs who have experienced an episode of GDV, and while the results varied, they were all frighteningly high – from about 18 percent to more than 30 percent. The rates used to be much higher, however.

“Veterinarians over the past two decades have reduced dramatically the postoperative fatality rate from gastric dilatation-volvulus from more than 50 percent to less than 20 percent by using improved therapy for shock, safer anesthetic agents, and better surgical techniques,” says Lawrence Glickman, VMD, DrPH, and lead researcher on a number of studies related to GDV at Purdue University in West Lafayette, Indiana.

In many acute cases of GDV, surgery is the only option to save the life of the animal. In addition to repositioning the stomach, it may also be “tacked” to the abdominal wall in a procedure called gastropexy. While dogs who have had gastropexy may experience gastric dilatation again, it is impossible for the stomach to rotate, as in volvulus or torsion.

What Causes Bloat in Dogs?

Theories about the causes of bloat in dogs abound, including issues related to anatomy, environment, and care. Research from Purdue University, particularly over the past 10 years, has shown that there are certain factors and practices that appear to increase the risk of GDV, some of which fly in the face of conventional wisdom.

“We don’t know exactly why GDV happens,” says Dr. Faggella. Some people do all of the “wrong” things, and their dogs don’t experience it, she says, while some do all of what we think are the “right” things, and their dogs do.

The most widely recognized and accepted risk factor is anatomical – being a larger, deep-chested dog. When viewed from the side, these dogs have chest cavities that are significantly longer from spine to sternum, when compared to the width of the chest cavity viewed from the front.

This body shape may increase the risk of bloat because of a change in the relationship between the esophagus and the stomach. “In dogs with deeper abdomens, the stretching of the gastric ligaments over time may allow the stomach to descend relative to the esophagus, thus increasing the gastroesophageal angle, and this may promote bloat,” says Dr. Glickman.

Can Small Dogs Get Bloat?

It isn’t just large- and giant-breed dogs that can bloat; smaller breeds do as well. “I’ve seen Dachshunds, Yorkies, and other small Terrier breeds with bloat,” says Dr. Faggella. She emphasizes that all dog guardians should be familiar with the signs of bloat, and be ready to rush their dog to the vet if any of the symptoms are present.

Likelihood of an incident of dog bloat seems to increase with age. Purdue reports that there is a 20 percent increase in risk for each year increase in age. This may be related to increased weakness, over time, in the ligaments holding the stomach in place, Dr. Glickman explains.

Another key risk factor is having a close relative that has experienced GDV. According to one of the Purdue studies that focused on nondietary risk factors for GDV, there is a 63 percent increase in risk associated with having a first degree relative (sibling, parent, or offspring) who experienced bloat.

Personality and stress also seem to play a role. Dr. Glickman’s research found that risk of GDV was increased by 257 percent in fearful dogs versus nonfearful dogs. Dogs described as having a happy personality bloated less frequently than other dogs. “These findings seem to be consistent from study to study,” adds Dr. Glickman.

Dogs who eat rapidly and are given just one large meal per day have an increased susceptibility to GDV than other dogs. The Purdue research found that “for both large- and giant-breed dogs, the risk of GDV was highest for dogs fed a larger volume of food once daily.”

The ingredients of a dog’s diet also appear to factor into susceptibility to bloat. A Purdue study examined the diets of over 300 dogs, 106 of whom had bloated. This study found that dogs fed a dry food that included a fat source in the first four ingredients were 170 percent more likely to bloat than dogs who were fed food without fat in the first four ingredients. In addition, the risk of GDV increased 320 percent in dogs fed dry foods that contained citric acid and were moistened before feeding. On the other hand, a rendered meat meal that included bone among the first four ingredients lowered risk by 53 percent.

Another study by Purdue found that adding “table foods in the diet of large- and giant-breed dogs was associated with a 59 percent decreased risk of GDV, while inclusion of canned foods was associated with a 28 percent decreased risk.” The relationship between feeding a home-prepared diet, either cooked or raw, hasn’t been formally researched.

Anecdotally, however, many holistic vets believe that a home-prepared diet significantly reduces the risk of bloat. “I haven’t seen bloat in more than five years,” says Monique Maniet, DVM, of Veterinary Holistic Care in Bethesda, Maryland. She estimates that 75 to 80 percent of her clients feed a raw or home-cooked diet to their dogs.

Dr. Faggella also noticed a difference in the occurrence of bloat while in Australia, helping a university set up a veterinary critical care program. “I didn’t see bloat as commonly there [as compared to the US],” she says. They feed differently there, with fewer prepared diets and more raw meat and bones, which may contribute to the lower incidence of GDV, she adds.

It is often recommended that limiting exercise and water before and after eating will decrease the risk of bloat. However, in one of the Purdue studies, while exercise or excessive water consumption around meal time initially seemed to affect likelihood of GDV, when other factors were taken into account, such as having a close relative with a history of GDV, in a “multivariate model,” these factors were no longer associated with an increased risk of bloat.

Or, more simply put, “there seems to be no advantage to restricting water intake or exercise before or after eating,” says Dr. Glickman.

How to Prevent Bloating in Dogs

Because the theories and research on what causes bloat aren’t always in agreement, the ways to prevent GDV can conflict as well. One thing that everyone can agree on, though, is that feeding smaller meals several times a day is the best option for reducing the risk.

One of the top recommendations to reduce the occurrence of GDV from the Purdue researchers is to not breed a dog that has a first-degree relative that has bloated. Results of their study suggest that “the incidence of GDV could be reduced by approximately 60 percent, and there may be 14 percent fewer cases in the population, if such advice were followed.”

In addition, Glickman says they recommend prophylactic gastropexy for dogs “at a very high risk, such as Great Danes. Also, we do not recommend that dogs have this surgery unless they have been neutered or will be neutered at the same time.”

The concern about performing a gastropexy on an unneutered dog is that it “might mask expression of a disease with a genetic component in a dog that might be bred.”

While gastropexy hasn’t been evaluated in its ability to prevent GDV from happening the first time, research has shown that just five percent of dogs whose stomachs are tacked as a result of an episode of GDV will experience a repeat occurrence, whereas up to 80 percent of dogs whose stomachs are simply repositioned experience a reoccurrence.

Raised Bowls Raise the Risk of Bloating

It has long been an accepted practice to elevate the food bowls of giant-breed and taller large-breed dogs. The theory is that, in addition to comfort, a raised food bowl will prevent the dog from gulping extra air while eating, which in turn should reduce the likelihood of bloat. However, this recommendation has never been evaluated formally.

It was included in the large variety of factors followed in a Purdue study,* and one of the most controversial findings. The research suggests that feeding from an elevated bowl seems to actually increase the risk of GDV.

The researchers created a “multivariate model” that took into account a number of factors, such as whether there was a history of GDV in a first-degree relative, and whether the dog was fed from an elevated bowl. Of the incidences of GDV that occurred during the study, about 20 percent in large-breed dogs and 52 percent in giant-breed dogs were attributed to having a raised food bowl.

The raw data, which doesn’t take into account any of the additional factors, shows that more than 68 percent of the 58 large-breed dogs that bloated during the study were fed from raised bowls. More than 66 percent of the 51 giant-breed dogs that bloated during the study were fed from raised bowls.

* These findings were reported in “Non-dietary risk factors for gastric dilatation-volvulus in large- and giant-breed dogs,” an article published November 15, 2000, in Volume 217, No. 10 of Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. The study followed more than 1,600 dogs from specific breeds for a number of years, gathering information on medical history, genetic background, personality, and diet.

Phazyme: The Controversial Gas-Reliever

After Remo’s death, Sharon Hansen learned that some large-breed dog owners swear by an anti-gas product called Phazyme for emergency use when bloat is suspected. Phazyme is the brand name of gelcaps containing simethicone, an over-the-counter anti-gas remedy for people. GlaxoSmith-Kline, maker of Phazyme, describes it as a defoaming agent that reduces the surface tension of gas bubbles, allowing the gas to be eliminated more easily by the body.

Less than a year and a half later, Hansen had an opportunity to try the product when her new rescue dog Bella, a Dane/Mastiff mix, bloated. “Bella came looking for me one afternoon, panting and obviously in distress,” explains Hansen, who immediately recognized the signs of bloat.

Hansen was prepared with caplets of Phazyme on hand. “I was giving her the caplets as we headed out to the car,” says Hansen. Almost immediately, Bella began to pass gas on the short ride to the vet. “She started passing gas from both ends,” Hansen says. By the time they arrived at the vet, Bella was acting much more comfortable, and seemed significantly less distressed.

At the vet’s office, gastric dilatation was confirmed, and luckily, there was no evidence of torsion. Hansen credits the Phazyme for reducing the seriousness of Bella’s episode. This is a generally accepted practice among guardians of bloat-prone dogs, but not all experts agree with it.

Dr. Faggella cautions against giving anything by mouth, as it could cause vomiting, which could lead to aspiration. “If you suspect bloat, simply bring your dog to the vet immediately. The earlier we catch it, the better,” she says.

Dr. Nancy Curran, DVM, a holistic vet in Portland, Oregon, agrees that trying to administer anything orally could lead to greater problems. However, she suggests that Rescue Remedy, a combination of flower essences that is absorbed through the mucous membranes of the mouth, may help ease the shock and trauma. “Rescue Remedy helps defuse the situation for everyone involved. It won’t cure anything, but it can be helpful on the way to the vet,” she says, recommending that the guardian take some as well as dosing the dog.

Holistic Prevention of Dog Bloat

“We may be able to recognize an imbalance from a Chinese medical perspective,” says Dr. Curran. She’s found that typically dogs prone to bloat have a liver/stomach disharmony. Depending on the dog’s situation, she may prescribe a Chinese herbal formula, use acupuncture, and/or suggest dietary changes and supplements to correct the underlying imbalance, thereby possibly preventing an episode in the first place.

Dr. Maniet also looks to balance a dog’s system early on as the best form of prevention. Each of her patients is evaluated individually and treated accordingly, most often with Chinese herbs or homeopathic remedies.

Both holistic vets also recommend the use of digestive enzymes and probiotics, particularly for breeds susceptible to canine bloat, or with existing digestive issues. “Probiotics and digestive enzymes can reduce gas, so I’d expect that they will also help reduce bloat,” explains Dr. Maniet.

Another avenue to consider is helping your fearful or easily stressed dog cope better in stressful situations. While no formal research has been conducted to confirm that this in fact would reduce the risk of bloat, given the statistics that indicate how much more at risk of GDV fearful dogs are, it certainly couldn’t hurt. Things to consider include positive training, desensitization, Tellington TTouch Method, calming herbs, aromatherapy, or flower essences.

While there is an abundance of information on how to prevent and treat bloat, much of it is conflicting. The best you can do is to familiarize yourself with the symptoms of GDV and know your emergency care options. While it may be difficult to prevent completely, one thing is clear. The quicker a bloating dog gets professional treatment the better.

Case History: Laparoscopically Assisted Gastropexy

On May 6, 2004, Dusty, a nine-year-old Doberman, was in obvious distress. “He was panting, pacing, and wanting to be near me,” his guardian, Pat Mangelsdorf explains. Dusty didn’t have any signs of tenderness or injury, and his appetite and elimination were fine. Mangelsdorf wasn’t sure what the problem could be. After a few hours, his behavior didn’t improve, so she took Dusty to the vet.

“By that time, he had calmed a bit, and there still wasn’t any tenderness or distension. Radiographs showed some arthritis in his spine, so we thought that was causing him pain,” she says. A few hours later, Dusty lay down to rest and seemed normal.

Three days later, Mangelsdorf received a surprise call. “A radiologist had reviewed the X-rays and noticed that Dusty had a partial torsion,” she says. The vet suggested that to help prevent another incident of torsion, Dusty’s activity level, food, and water should be more tightly controlled, and a gastropexy should be considered to rule out future occurrences.

Mangelsdorf began researching her options. Was the surgery necessary? If so, which would be best, the full abdominal surgery or the laparoscopic procedure? Before she could decide, Dusty had another apparent torsion episode. “He had exactly the same symptoms,” says Mangelsdorf. Dusty spent a night at the emergency clinic, and more radiographs were taken, but they were inconclusive. Nevertheless, Mangelsdorf had made up her mind.

After reviewing the options and the potential risks and rewards, Mangelsdorf opted for a laparoscopically assisted gastropexy, rather than a traditional gastropexy with a full abdominal incision. “A laparoscopic gastropexy is minimally invasive, with just two small incisions,” explains Dusty’s surgeon, Dr. Timothy McCarthy, of Surgical Specialty Clinic for Animals in Beaverton, Oregon. Dr. McCarthy, who specializes in minimally invasive surgeries and endoscopic diagnostic procedures, has been performing this type of gastropexy for about four years.

This specialized procedure for gastropexy was developed by Dr. Clarence Rawlings, a surgeon and professor of small animal medicine at University of Georgia. The technique involves two small incisions. The first incision is to insert the scope for visualizing the procedure, the second incision is used to access the stomach for suturing. After palpating the stomach, it is pulled up toward the abdominal wall, near the second incision. The stomach is then sutured directly to the abdominal wall, as in a standard gastropexy. The incisions are then closed as normal, usually with staples.

“This is a very quick procedure. An experienced surgeon can do it in 15 minutes,” says McCarthy. While quick, the surgery isn’t inexpensive. It costs about $1,500 at McCarthy’s clinic.

On July 27, Dusty underwent surgery. The procedure went well, without any complications. Later that evening, Dusty started heavy panting and shivering, but X-rays and bloodwork showed everything normal. With IV fluids, he was more settled in a few hours, and back to normal by morning.

“Afterwards, we did short walks, no stairs, and three or four small meals a day for two weeks,” says Mangelsdorf. Gradually, she increased Dusty’s exercise until he was back to normal levels. She added acidophilus as well as more moisture into his diet, including cottage cheese and canned food, while keeping his water bowl at lower levels so he doesn’t drink excessive amounts at any one time.

Shannon Wilkinson, of Portland, Oregon, is a freelance writer, life coach, and TTouch practitioner.

Therapeutic Essential Oils for Your Dog

Last month’s aromatherapy article (“Aromatherapy for Dogs“) introduced therapeutic shampoos, spritzes, and massage oils. If you and your dog tried any of the wonderful products recommended there, you may be ready to buy some essential oils and try your own custom blending for maximum effects.

Welcome to canine aromatherapy. According to Kristen Leigh Bell, author of Holistic Aromatherapy for Animals, “It’s hard to imagine a condition that can’t be prevented, treated, improved, or even cured with the help of essential oils.”

Bell mentions dozens of health problems that have resolved with the help of aromatherapy, from allergies to anxiety, bad breath to burns. It’s a fascinating branch of holistic medicine.

Essential oils, the foundation of aromatherapy, are the volatile substances of aromatic plants. They are collected, usually by steam distillation, from leaves, blossoms, fruit, stems, roots, or seeds. The water that accompanies an essential oil during distillation is called a hydrosol or flower water. Hydrosols contain trace amounts of essential oil and are themselves therapeutic. Other production methods include solvent extraction (a solvent removes essential oil from plant material and is then itself removed), expression (pressing citrus fruit), enfleurage (essential oils are absorbed by fat for use in creams), and gas extraction (room-temperature carbon dioxide or low-temperature tetrafluoroethane gas extracts the essential oil and is then removed). Each method has something to recommend it for a specific plant or type of plant.

However they are collected, essential oils are highly concentrated. To produce one pound of essential oil requires 50 pounds of eucalyptus, 150 pounds of lavender, 400 pounds of sage, or 2,000 pounds of rose petals. No wonder they’re expensive!

It’s not the fragrance that imparts the medicinal or active properties of aromatic essential oils but the chemicals they contain. Essential oils can contain antibacterial monoterpene alcohols or phenylpropanes, stimulating monoterpene hydrocarbons, calming esters or aldehydes, irritating phenols, stimulating ketones, anti-inflammatory sequiterpene alcohols, antiallergenic sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, and expectorant oxides.

Plants are complex chemical factories, and a single plant may contain several types of chemicals. In addition, each chemical category may have several different effects. Aromatherapy is a modern healing art, and the therapeutic quality of essential oils are still being discovered. In other words, aromatherapy is a complex subject that deserves careful study and expert guidance.

Start with Lavender

What essential oil should you start with? Everyone’s favorite is lavender, Lavandula angustifolia, a powerful disinfectant, deodorizer, and skin regenerator. It helps stop itching and has psychological benefits; it’s both calming and uplifting. Lavender is one of the few essential oils that can safely be used “neat” or undiluted, though dilution is recommended for most pet applications.

Here are a dozen things to do with a therapeutic-quality lavender essential oil:

1) Diffuse it in the room with an electric nebulizing diffuser (available from aromatherapy supply companies).

2) Add 10 to 20 drops to a small spray bottle of water and spritz it around the room. Be careful to avoid wood or plastic surfaces and your dog’s eyes.

3) Place a drop on your dog’s collar, scarf, or bedding.

4) Place two drops in your hand, rub your palms together, and gently run your hands through your dog’s coat.

5) Add 15 to 20 drops to 8 ounces (one cup) of unscented natural shampoo, or add a drop to shampoo as you bathe your dog.

6) Add two to five drops to a gallon of final rinse water and shake well before applying (avoid eye area).

7) Place a single drop on any insect or spider bite or sting to neutralize its venom (avoid eye area; dilute before applying near mucous membranes).

8) Add 12 to 15 drops to one tablespoon jojoba, hazelnut, or sweet almond oil for a calming massage blend.

9) Place a drop on a dog biscuit for fresher breath.

10) Add 15 to 20 drops to a half-cup of unrefined sea salt, mix well, and store in a tightly closed jar. To make a skin-soothing spray or rinse for cuts or abrasions, dilute one tablespoon of the salt in a half-cup of warm water.

11) Mix one teaspoon vegetable glycerine (available in health food stores) with one teaspoon vodka. Add 15 drops lavender essential oil, and add two ounces (four tablespoons) distilled or spring water to make a soothing first-aid wipe, ear cleaner, or wound rinse. Saturate a cotton pad, mist from a spray bottle, or apply directly to cuts or scrapes.

12) To remove fleas while conditioning your dog’s coat, wrap several layers of gauze or cheesecloth around a slicker or wire brush, leaving an inch or more of bristles uncovered. Soak the brush in a bowl of warm water to which you have added 10 to 12 drops of lavender essential oil, and brush the dog. Rinse and repeat frequently, removing hair, fleas, and eggs.

You can also blend lavender with other essential oils for a limitless variety of applications. Bell’s favorites for pet use are listed in the sidebar “Top 20 Essential Oils for Use With Pets.” “With these oils,” she says, “you can address a variety of common ailments: treat wounds; clean ears; stop itching; calm and soothe; deodorize; and repel fleas, ticks, and mosquitoes.”

Let Your Dog Pick an Essential Oil

Colorado aromatherapist Frances Fitzgerald Cleveland does more than consider which essential oils will work; she lets canine patients make the final selection.

“For any condition, there are several essential oils that would help,” says Cleveland. “For example, a dog who suddenly becomes afraid of loud noises and needs a calming oil would be helped by lavender, rose, violet leaf, basil, Roman chamomile, yarrow, or vetiver. But before giving her anything, let her smell each oil. I usually do this by offering the cap. If she runs to the other side of the room or turns her head away, that’s not the right oil to use. Don’t force it on her. Wait for her to find an oil she’s interested in, that she wants to smell more of. She may even try to lick the cap.”

Once you’ve found an essential oil that will treat the problem and that agrees with your dog, Cleveland suggests blending it with an easily digested vegetable oil, such as cold-pressed safflower oil. “Fill a five-millilter bottle (which holds about one teaspoon) with the vegetable oil and add three to five drops of the essential oil. Now put a few drops on your fingertips and offer your hand to her. She might lick it off your fingers. Then apply a couple of drops to her paws and to a bandana scarf tied around her neck.

“It’s fascinating to watch how these animals respond,” Cleveland continues. “I’ve seen it work with my own animals and with clients’ animals, and I’ve had an opportunity to work with orangutans and gorillas at the Denver Zoo. For all animals, but especially those who have been abused or who have never had an opportunity to make their own decisions in life, this approach is exciting because they get to choose, they get to say yes or no. Listening to what your dog has to say is important, plus it’s a great way to bond. You’re not doing anything threatening, you’re doing something helpful and healing, and the animals respond.”

Essential Oil Blending Secrets

Selection in hand, you can blend a massage oil, coat spray, or other product that your dog will readily accept.

Essential oils can be diluted in vegetable carrier oils, preferably organic and cold-pressed, such as apricot kernel, coconut, hazelnut, jojoba, olive, sesame, sweet almond, or sunflower oil. The general rule for canine use is to mix one teaspoon carrier oil with three to five drops essential oil or one tablespoon (½ ounce) carrier oil with 10 to 15 drops essential oil. Use standard measuring spoons, not tableware, to measure carrier oils; use an eyedropper or a bottle’s built-in dispenser to measure drops. There are about 20 drops in 1 milliliter (ml), 15 drops in ¼ teaspoon, and 60 drops in a teaspoon of most essential oils.

Essential oils can be mixed with water, but they will not dissolve. One way to dissolve essential oils in water is to add them to a small amount of grain alcohol, vodka, sulfated castor oil (also called Turkey red castor oil), vegetable glycerin, or any combination of these ingredients. Then add water, herb tea, aloe vera juice, hydrosol, or other liquid.

Because essential oils don’t dissolve in water, they can’t be rinsed away. If a drop of essential oil ever lands where it shouldn’t, such as in your eye – or worse, your dog’s eye – use a generous amount of carrier oil to remove it. Always keep vegetable oil and paper towels or soft cloths on hand for this type of emergency.

Also With This Article

“Top 20 Essential Oils for Dogs”

“Tea Tree Oil Diffusers Are Toxic to Dogs”

“Healing Oils For Your Dog”

-CJ Puotinen is author of The Encyclopedia of Natural Pet Care (Keats/McGraw-Hill) and Natural Remedies for Dogs and Cats (Gramercy/Random House). She wrote the foreword for Kristen Leigh Bell’s Holistic Aromatherapy for Animals.

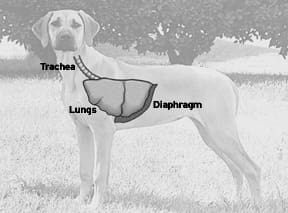

Understanding the Dog Respiratory System

The dog respiratory system or any respiratory system functions rather miraculously. Vital for life, critical for the health of the whole body, it’s one of the major ways the dog’s body unites his external environment with his inner milieu. As a primary site of contact with the outer world, the lungs are susceptible to diseases that can be caused by any airborne germ, irritant, or toxin that happens to be floating around.

Holistic practitioners understand that respiratory symptoms can be an indication of disease or a sign of healing – the key is differentiating between the two. Some alternative and complementary medicines have proven to be beneficial for many respiratory conditions, especially mild diseases and those that have become chronic.

Architecture of respiration

In addition to the nose, larynx, and pharynx (which were discussed in detail in “Know the Nose,” WDJ November 2004), the respiratory system consists of the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, alveoli, and the parenchymal tissue of the lungs.

From the trachea to the alveoli, a map of the lungs would look like a tree – each branch dividing into many, ever-smaller branches until the end point of several million alveoli is reached. Each alveoli is a round receptacle where gas exchange occurs via contact of the inspired air with blood across an extremely thin layer of tissue surrounding the alveolar capillaries.

The respiratory system performs several functions. Its most important utility is to act as a gas exchange: it delivers oxygen for distribution to the body, and removes carbon dioxide produced by living cells. In addition, the respiratory system filters out particulate matter, maintains the body’s acid-base balance, acts as a blood reservoir, protects its own delicate airways by warming and humidifying inhaled air, and is active in producing substances that initiate the immune system response. The upper airways also provide for the sense of smell and play a role in temperature regulation in panting animals.

Normal respiratory rates vary, depend-ing on the size of the dog, from 10 to 30 breaths per minute; larger dogs have slower rates. Panting – a rapid, open-mouthed, and shallow breathing pattern – is a normal canine reaction, brought on by exercise and/or the need to cool the body.

In the healthy animal, particulate matter and the small amounts of mucus that are normally generated are removed by cilia (minute hairs that line the trachea and bronchi) and coughed up or swallowed. Many microorganisms live in the normally healthy respiratory system; their pathogenicity is held in check by local and systematic immune factors.

According to Western medical practitioners, disease of the respiratory system occurs when irritants greatly increase the amount of mucus produced (in excess of what the animal can expel naturally), when the immune system allows for attachment and growth of pathogenic microorganisms, or when local cells are stimulated to become malignant (from excess exposure to carcinogenic toxins, for example).

Alternative view

Traditional healers have long respected the healing power of correct breathing, and their ways of thinking about the respiratory system reflect this understanding.

For many cultures the breath is equivalent to the Qi (pronounced “chee” and often spelled chi) or Prana (vital force) that circulates throughout the body and gives it life and vitality. From this view, respiratory disease may be considered the result of a weakened protective Qi – from a deficiency of Lung Qi production or dissemination.

In most Eastern cultures (and some other cultures) considerable attention is paid to helping people stay healthy by teaching them proper breathing methods – through various forms of meditation, postures (yoga asanas), and active or passive exercises meant to enhance proper breathing.

In Traditional Chinese Medicine the lungs are thought to regulate the Qi of the entire body; a disharmony of the lungs can produce deficient Qi or stagnant Qi anywhere in the body.

The Chinese herbal mixture “Jade Screen” – which includes astragalus (Astragalus membranaceus) – and acupressure points are often used by traditional Chinese medical practitioners to strengthen both Lung and protective Qi. These practitioners also credit the lungs with helping to move moisture through the body. Disharmonies of the lungs’ water-moving function, they say, can result in urinary dysfunction, edema (especially in the upper body), or problems with perspiration. A dog with robust lung health will have a bright, shiny coat and will be resistant to developing colds, persistent coughs, and other aggravating illnesses.

Signs of disease

Any kind of practitioner would recognize coughing as a first sign of respiratory dis-ease. A sudden onset of coughing may be a dramatic indicator of serious disease – pneumonia, secondary symptoms of other viral diseases such as distemper, or lung tumors – or not-so-serious disease, such as common colds or kennel cough.

There are also more subtle signs to watch for, and since some of these signs may be related to either heart or lung problems, it is important to differentiate between the two. Exercise intolerance is the most prominent of these signs. A dog will demonstrate this by lagging back during her daily walks; wheezing, gasping, and straining for air when she is forced to exercise, when she climbs a flight of stairs, or jumps up on your bed; and she may tend to sit in an elbows-out posture. Exercise intolerance and the accompanying signs listed above are the classic symptoms of heart disease, and whenever they are seen, it is time for a visit to the veterinarian.

The same symptoms as those seen with heart disease, however, may also be a sign of aging. Some experts believe that the respiratory system declines in efficiency by up to 50 percent over a lifetime. Bronchial passages constrict, fibrous tissue in lungs increases, and the functional capacity of the alveoli is reduced. In addition, many dogs, over the years, have been exposed to lung damage caused by inhaled allergens, foreign bodies, and microorganisms – all of which can decrease functional lung capacity.

Your dog should visit his vet at least once a year for an annual physical – perhaps twice a year after he’s reached about seven years of age. Use a veterinarian who takes the time to put a stethoscope to the dog’s heart and chest to listen for abnormal sounds. If there is some question about the functional capacity of your dog’s heart or lungs, further testing such as radiographs or an EKG may be indicated.

My own feeling is that the annual physical is absolutely necessary, to monitor how the dog is doing on a yearly basis. Please note that an annual vaccine is absolutely unnecessary, although this is the reason many vets give for seeing your dog every year. In my opinion, it is time for those of us in the veterinary profession to concentrate on the annual physical exam rather than on selling vaccines.

Kennel cough and colds

The two most common afflictions of the respiratory system are the “common cold” and kennel cough. Both of these ailments are usually instigated by any of a number of viruses, often followed by secondary bacterial invasion. The severity of the symptoms varies widely, but in most “colds” they are mild and include wheezing, coughing, reluctance to move, and perhaps a mild fever.

Kennel cough (a.k.a. infectious tracheobronchitis), on the other hand, can produce symptoms that appear extreme, with a dry, hacking cough accompanied by frequent, intense gagging. I’ve had caretakers rush their kennel-coughing dog in to see me, thinking he has a bone caught in his throat. Despite its appearance, a typical case of kennel cough is not life-threatening, and it tends to run its course in a few days to a week or so. But it is a disease that is frustrating for pet and caretaker alike.

Kennel cough results from inflammation of the upper airways. The instigating pathogen may be any number of irritants, viruses, or other microorganisms, or the bacteria Bordetella bronchiseptica may act as a primary pathogen. The prominent clinical sign is paroxysms of a harsh, dry cough, which may be followed by retching and gagging. The cough is easily induced by gentle pressure applied to the larynx or trachea.

Kennel cough should be expected whenever the characteristic cough suddenly develops 5 to 10 days after exposure to other dogs – especially to dogs from a kennel (especially a shelter) environment. Usually the symptoms diminish during the first five days, but the disease may persist for up to 10-20 days. Kennel cough is almost always more annoying (to dog and her caretaker) than it is a serious event.

Other diseases of the respiratory system

Pneumonia is inflammation of the lungs with consolidation (hardening) of the tissues, and this inflammation can be from any number of sources – viral, bacterial, fungal, trauma-induced, or as the consequence of an allergic reaction. Oftentimes the initial stimulus for inflammation comes from airborne toxins – cigarette smoke, city smog, fumes from household cleansers, and outgassing from numerous sources such plastic food dishes or the formaldehyde found in household insulation, new carpets, and furniture.

Pneumonia is not a common malady in dogs, and when it occurs, the symptoms may vary from mild to extreme; in severe cases the disease can be life-threatening. If your dog has extreme difficulty breathing, or if he has stopped eating and is very reluctant to move, it’s time to see the vet. Antibiotics and supplemental oxygen can be lifesaving at this stage.

Likewise, neither asthma nor emphy-sema are common problems in dogs, although they do occasionally occur. Asthma is a condition that causes recurrent bouts of wheezing and respiratory distress due to constriction of the bronchi, and is often allergy-induced. Emphysema is an abnormal accumulation of air in the spaces between the alveoli of the lungs. Both conditions can be difficult to diagnose correctly, often requiring radiographs to determine the extent of damage.

Any dog who demonstrates periodic bouts of respiratory distress or who has had a chronic problem with breathing should be taken to a veterinary hospital for further evaluation. Holistic veterinarians (including me) have had excellent success treating asthma using acupuncture, coupled with immune-system boosters and other herbs to aid breathing.

Trauma that causes tissue damage and/or bleeding into the lungs can also be a cause of respiratory distress. The typical lung trauma case goes something like this: The dog arrives at the emergency clinic in respiratory distress. The owner reports that the dog had been out running loose for a while and he returned like this – a sudden onset. These dogs have often been hit by a car, and the major damage has been internal, to the lungs or diaphragm. Again, whenever your dog is in extreme respiratory distress, it is time to visit your vet.

Respiratory involvement can come secondarily, from other sources in the body, such as an extension of gingivitis from the mouth, diabetes (which lowers resistance to disease), and other infections such as distemper, parainfluenza, or adenovirus. The most common source of secondary respiratory problems, however, comes from the heart.

Cardiac insufficiency, whatever the cause, can cause a decrease in respiratory efficiency, and the clinical signs of coughing, wheezing, and exercise intolerance. Heart conditions, including heartworm infection, need to be differentiated from primary lung involvement, and your vet’s stethoscope is the first step here, perhaps followed up with X-rays and other tests.

Lung tumors can be either primary (originating in the lung tissues) or secondary (metastasizing from other parts of the body and lodging in the lung tissues). Both of these can create nasty tumors that are difficult to treat, whatever method you choose to use. My experience with these is that if there is anything that can help them, it will be classical homeopathic remedies. Since it is thought that many lung tumors are instigated by contact with airborne toxins, it’s important that we do all we can to eliminate them from our own and our dog’s environment.

Care of the respiratory system

Oxygen is the most lung-friendly nutrient available for man or beast. Make sure your dog’s lungs (and outlying tissues) are adequately supplied with oxygen, by taking – at minimum – a daily 20- to 30-minute walk at an easy trot pace (the pace where you can carry on a normal conversation with your dog so passersby will think you are crazy).

I also think that a daily anaerobic romp – sprinting to retrieve a ball, for example – helps to expand the functional capacity of the lungs. Be sure to have your dog’s heart and lungs evaluated by a vet before you begin a new exercise program.

The second most important thing to do for the health of your dog’s lungs is to eliminate all the toxins you possibly can. Many of the commonly found air pollutants cause irritation to the airways of the lungs and this irritation stimulates mucus production. The mucus in turn stimulates coughing. Other irritants cause the smooth muscles to constrict around the alveoli, eventually causing asthma or emphysema. Finally, many of the air pollutants are known carcinogens; persistent contact with them is a disaster waiting to happen.

While exploring ways to eliminate air pollutants is beyond the scope of this article, it is definitely a topic for you and your family to explore. As a first step, though, make sure your (and your dog’s) house and living environment have adequate ventilation.

The next (and final) step to assuring respiratory health is to energize the immune system. Proper diet, limited stress, along with vitamins A, C, and E and other antioxidants such as the culinary herbs and Coenzyme Q10 are all beneficial to the immune system. Herbs that are directly beneficial for the immune system include echinacea and astragalus. Check with your holistic vet for correct dosages of these supplements and herbs.

Alternative medicines for respiratory conditions

There are two important things to remember about alternative medicines and the respiratory system:

1) In Western medicine, it is often impossible to treat a condition without knowing the cause; in most alternative medicines (Chinese medicine and homeopathy in particular), the treatment is always for the condition itself, regardless of the cause.

2) Holistic treatments begin with the realization that most respiratory infections are really signs of the body’s healthy effort to expel toxicity – via mucus from the nose, sneezing, puffy red eyes with mucus-like secretions, and coughing and phlegm.

While the Western medicine man will focus intensely on diagnostic procedures to try to determine a specific diagnosis, the alternative practitioner observes symptoms as they occur and treats accordingly. And, whereas the Western practitioner’s treatments are often aimed toward palliation of symptoms (easing the cough, for example), the alternative practitioner understands that respiratory symptoms may be a good sign that the body is responding in a healing manner.

• Herbs. There are several herbs that may be beneficial for treating respiratory conditions. The following have been used to treat the symptoms seen with respiratory disease. Herbal dosages and method of delivery vary with the needs of the animal; check with your herbal practitioner.

Herbs that enhance the immune system include echinacea (Echinacea spp.), astrag-alus (Astragalus membranaceus), Siberian ginseng (Eleutherococcus senticosus).

Herbs with antibiotic activity (for lung infections) include Oregon grape root (Mahonia aquifolium), goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), and echinacea. Herbs for bronchial congestion include oregano (Origanum vulgare), bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis), thyme (Thymus vulgaris), and ginger (Zingiber officinale).

Herbs for acute bronchitis include marshmallow (Althaea officinalis), cinnamon (Cinnamonum camphora), turmeric (Curcuma domestica), echinacea, fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla), and peppermint (Mentha piperita).

To ease coughing, try the following herbs: marshmallow, pleurisy root (Asclepias tuberose), oats (Avena sativa), calendula (Calendula officinalis), licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra), peppermint, elder (Sambuscus nigra), thyme, coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara), and mullein (Verbascum thapsus).

My own preference has been to use licorice root to ease the cough (and for its adaptogenic qualities), echinacea for its immune-stimulating properties, and Oregon grape root for its infection-fighting abilities. I then consider adding other herbs as the symptoms indicate.

• Massage may prove beneficial in preventing and treating respiratory diseases. Dogs can become very anxious whenever their breathing is difficult or restricted, and anxiety tends to constrict breathing. A whole-body massage may be relaxing enough to help produce more normal breathing patterns.

• Acupuncture is one of the best ways to treat respiratory disease, and it has been shown to be especially helpful for treating asthmatic patients. Acupuncture points along the Lung and Large Intestine Meridian are the primary points to use, with additional points possibly located along the Spleen, Kidney, and/or other Meridians, depending on the symptoms.

When treating a wet cough, in addition to herbs for bronchial conditions and coughing (see the herbal section, above), your veterinary acupuncturist will consider removing “dampness” from the lungs by needling the Spleen-6 and Kidney-3 acupressure points, while also enhancing the immune system by stimulating Large Intestine-11. You can use acupressure on the same spots (ask your acupuncturist to show you their locations). Use moderate pressure over the spots for several minutes, or until your dog seems to be uncomfortable with the pressure. Don’t continue past that point!

The Lung and Large Intestine Meridians (the paired Meridians that are associated with lungs and respiratory function) run on either side of the dog’s forearm; to stimulate points along this meridian, massage up and down the forearm beginning at the shoulders and extending down to the dew claw and first digit of the paws.

Each Organ system, in the Traditional Chinese Medicine way of thinking, has an emotional component attached to it. Sadness and grief are related to the lungs, and an excess of sadness or grief may weaken Lung Qi.

• Flower essences can be very helpful for treating emotional disturbances, and if your dog has problems with lung disease, especially if the problems are persistent or recurring, think about the possibility of sadness or grief as contributing factors. Consider flower essences whenever there is the potential for your dog to be sad or grieving, such as when a human member of the family leaves through divorce, or a four-footed companion who has lived with the family passes on.

When your dog seems to be grieving, try the flower essence remedies Star of Bethlehem, pine, and/or wild rose. If she seems to be extremely gloomy and utterly sad, try mustard or wild rose. If the sadness is the result of homesickness (from a recent move, for example) try honeysuckle and clematis. Walnut is an excellent remedy anytime there has been a transition in the family – a family member suddenly leaving, for example, or after moving from one house to another.

Flower essences can be used singly, or up to five remedies can be combined and used together. Remedies are typically diluted. Use several drops per ounce of spring water, and a few drops of this dilution can then be given orally, a few drops added to the dog’s water, or the diluted solution can be placed in a misting bottle and spritzed over the dog’s body. (See “Flower Power,” March 1999, for more information about flower essence remedies.)

• Homeopathic remedies. There are literally dozens of homeopathic remedies that have been shown to be helpful for treating all sorts of respiratory illnesses, again depending on the symptoms observed. Examples include:

• For a dry, spasmodic cough: Belladonna, Bryonia, Stannum

• For coughing and difficult breathing: Arsenicum alb., Kali carb., Lycopodium, Phosphorous

• For asthmatic breathing: Apis, Sulphur, Lobelia inflata

• For cases of “heart cough”: Naja, Prunus v., Spongia

For more information about homeopathy, see “Tiny Doses, Huge Effects,” WDJ June 2000.

Also With This Article

Click here to view “The Many Causes of Kennel Cough”

Click here to view “Kennel Cough Treatment and Prevention”

Click here to view “Determining the Cause of Your Dog’s Panting”

-Dr. Randy Kidd earned his DVM degree from Ohio State University and his PhD in Pathology/Clinical Pathology from Kansas State University. A past president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, he’s author of Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Dog Care and Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Cat Care.

Limber Tail Syndrome

If your dog’s tail suddenly starts lying limply or stops wagging in wag-worthy situations, she may have limber tail syndrome—a temporary but uncomfortable condition that affects the muscles near the base of the tail. While it typically occurs after overexertion, exposure to cold, or long periods of confinement, the exact cause is unknown. Though it can look alarming, limber tail typically resolves within a few days to a week with rest and supportive care. Understanding the causes, symptoms, and treatment options can help owners recognize the condition quickly, ease their dog’s discomfort, and prevent future flare-ups.

What Does Limber Tail Syndrome Look Like?

One day last summer, Lucky, my normally exuberant mixed-breed dog, returned with my husband from an off-leash hike exhibiting little of her boundless energy. She made a beeline for her bed, so we joked that she was out of condition; she’d had knee surgery six months earlier and we assumed she hadn’t fully regained her stamina.

But as the hours ticked by and she continued to show little interest in moving, we got concerned. She changed positions very gingerly and seemed to have a hard time sitting and lying down. Worse, we couldn’t even coax a single happy tail thump from a dog who usually wielded that appendage with abandon. She looked at us with sad eyes and drooping ears, telegraphing that something wasn’t right.

I started worrying about all the possible things that could have happened. Did she eat something foul on the trail? Had she re-injured her knee? She was eating and drinking, and her temperature was normal, but clearly this was not a healthy animal. An emergency examination was in order.

Our veterinarian examined her from stem to stern, and it was in that latter area she spotted the problem. “I think she has a sprained tail,” she opined. “It should heal on its own within a week, but if she seems really tender, you can give her an anti-inflammatory.”

Sure enough, within four days Lucky’s drooping and strangely silent tail regained both its loft and its wag. Still, I was surprised that in the years I’ve written about dogs I’d never heard of a sprained tail. It turns out that the malady is well known among trainers and handlers of certain dog breeds, and while “sprain” is something of a misnomer, the affliction has a formal name: limber tail syndrome.

You might suspect your dog has limber tail syndrome if:

- The tail is somewhat or completely limp.

- Your dog has difficulty sitting or standing.

- There was no obvious injury (i.e., a slamming door or an errant foot) to the tail.

- It occurs soon after extreme activity, prolonged transport, a swim in cold water, or a sudden climate change.

- His vital signs are good and he’s still eating and drinking normally, despite the floppy tail.

- The tail shows gradual improvement over a few days.

- To view a video of a dog with limber tail,see Youtube.

What is Limber Tail Syndrome?

Limber tail syndrome seems to be caused by muscle injury possibly brought on by overexertion, says Janet Steiss, DVM, PhD, PT. Steiss is an associate professor at Auburn University’s College of Veterinary Medicine and coauthor of the 1999 study on limber tail that pinpointed the nature of the muscle damage. Researchers used electromyography (EMG), imaging, and tissue testing on dogs affected with limber tail and concluded that the coccygeal muscles near the base of the tail had sustained damage.

The muscle injury of limber tail is characterized by a markedly limp tail, which can manifest in several different ways.

“You can see varying degrees of severity,” says Dr. Steiss. “The tail can be mildly affected, with the dog holding the tail below horizontal, or severely affected, hanging straight down and looking like a wet noodle, or anything in between.”

In some dogs, the tail may stick out a couple of inches before drooping; others may exhibit raised hair near the base of the tail as a result of swelling. Depending on the severity of the injury and the dog’s tolerance to pain, some animals – like Lucky – may have difficulty sitting or lying down. And many dogs reduce or eliminate wagging entirely, probably due to soreness.

Limber tail can occur in any dog with an undocked tail, but certain breeds, especially pointing and retrieving dogs, seem particularly susceptible to it. Among these breeds are Labrador, Golden, and Flat-Coated Retrievers; English Pointers and Setters; Beagles; and Foxhounds. Both sexes and all ages can be affected. Other common names for the condition are “cold tail” or “swimmer’s tail” (especially among Retrievers, who often exhibit symptoms after swimming in frigid water). It is also sometimes called “limp tail,” “rudder tail,” “broken tail,” or even “dead tail.”

The condition resolves over the course of a few days or a week and usually leaves no aftereffects. According to Dr. Steiss, there is anecdotal evidence that administering anti-inflammatory drugs early in the onset can help shorten the duration of the episode, but no veterinary studies have yet confirmed this.

What Causes Limber Tail Syndrome?

The exact cause is unknown, but according to Dr. Steiss, there are a few different factors that seem to be linked to limber tail. Overexertion seems to be a common precursor, especially if an animal is thrown into excessive exercise when he or she is not in good condition (as in Lucky’s case).

“For example, if hunting dogs have been sitting around all summer and then in the fall, the owner takes them out for a full (weekend of hunting), by Sunday night suddenly a dog may show signs of limber tail,” she says. “The dog otherwise is healthy but has been exercising to the point where those tail muscles get overworked.”

Another risk factor is prolonged confinement, such as dogs being transported in crates over long distances. If competition dogs are driven overnight to a field trial and don’t have a few breaks outside the crate while they’re on the road, says Dr. Steiss, they may arrive at their destination with limber tail.

Uncomfortable climates, such as cold and wet weather, or exposure to cold water may also trigger limber tail. Retrievers seem particularly prone to exhibiting symptoms after a swimming workout, and some, says Dr. Steiss, are so sensitive to temperature that they show signs of limber tail after being bathed in cold water.

Limber Tail Syndrome: A Tricky Diagnosis

For an owner, the sight of a normally active tail hanging lifelessly can be alarming. After all, dogs’ tails are barometers of both mood and health, and a tail carried low and motionless could indicate anything from nervousness to serious illness. Limber tail syndrome has been around for a long time, but it isn’t very common and many veterinarians – especially those who don’t work regularly with hunting or retrieving dogs – aren’t familiar with it. Consequently, a variety of diagnoses can be given.

Is Limber Tail Syndrome a Sprained Dog Tail?

Limber tail can be mistaken for an indication of a disorder of the prostate gland or anal glands; a caudal spine injury; a broken tail; or even spinal cord disease. The all-purpose phrase “sprained tail” might also be used.

Ben Character, DVM, a consulting veterinarian in Eutaw, Alabama, and a member of the American Canine Sports Medicine Association, specializes in sporting dogs. He’s seen plenty of cases of limber tail but doesn’t call it a sprain.

“Sprain is a bad word for it because a sprain indicates a joint and problems with the ligaments surrounding a joint,” Dr. Character explains. “As far as we know, this is all muscular.”

” ‘Sprained tail’ is kind of a catchall, non-specific phrase that simply means something’s wrong with the tail,” agrees Dr. Steiss. “The tail has all kinds of joints because it has many tiny vertebrae, but sprain isn’t the correct term here.”

How can an owner tell if limber tail is the cause of a dog’s discomfort? Look to the circumstances surrounding the onset of the droopy tail, suggests Dr. Steiss, especially if any of the risk factors were present.

“Limber tail has an acute onset. It is not a condition where the tail gets progressively weaker,” she says. “Instead, it is an acute inflammation. Typically, the tail is suddenly limp and the dog may seem to have pain near the base of the tail. Over the next three to four days, the dog slowly recovers to the point where by four to seven days he’s usually back to normal.”

Dr. Character says it’s a tough clinical call to make. “In order to really diagnose limber tail, you’d have to do electromy-opathy (of the tissue) or do radiography to examine the inflammation, and a general practitioner just won’t be able to do that.”

Effects of Limber Tail

While an episode of limber tail can be unsettling for an owner, it doesn’t hamper most dogs’ ability to function normally.

“For your average hunting dog, it probably won’t make a difference,” says Dr. Character. “The tail is involved in balance when they run, but how much that’s going to knock them off their game . . . it may not be enough to notice.”

However, competition dogs can be sidelined: “Athletic dogs competing in field trials will not be able to compete when the tail doesn’t have its normal motion, since the condition will be obvious to the judges,” says Dr. Steiss.

Limber tail doesn’t recur with any regularity among dogs that have already experienced one episode, according to Dr. Steiss: “In the majority of cases it happens once and doesn’t happen again,” she says. “But there are a few dogs where, if put into the same situation, it happens more than once.”

That was the case with Hannah, a Lab/Pit Bull mix owned by Miriam Carr, a dog care specialist in Richmond, California. Carr operates a dog-exercise business, PawTreks, specializing in off-leash outings. Often, Carr’s trips include swimming opportunities for her clients’ dogs. Her own dogs, of course, get to participate in every outing. “Hannah was very active – she went to the park every single day – so she was in great condition,” says Carr.

After Hannah suffered several incidents of limber tail, however, Carr had to limit the dog’s participation in the activities that seemed to trigger the limber tail incidents. “When Hannah swam with other dogs she was more competitive and would swim harder to get to the ball first, and that sort of set off the problem with her tail,” says Carr. “When we finally realized that was the problem, we wouldn’t let her swim with groups of dogs.”

It was smart management on Carr’s part. In rare cases, a dog’s tail can be permanently affected by recurrent episodes, says Dr. Steiss. “A few can injure the muscle so severely that the tail may not be straight again. Probably, there’s been a significant loss of muscle fibers plus scar tissue build-up in the tails in those dogs,” she explains.

Limber Tail Syndrome Treatment and Care

- Check with your vet to rule out any other possible ailments.

- Rest your dog.

- Ask your vet if an anti-inflammatory medication may be appropriate for the first 24 hours. (See “Administer With Care” for more information and warnings about anti-inflammatory use.)

- Gradually return your dog to activity.

- Try to determine what factors seemed to cause the limber tail and avoid them in the future.

Do More Dogs Have Limber Tail Now Than in the Past?

Before 1990, limber tail wasn’t often recognized outside hunting- and sporting-dog circles. But in 1994, Auburn University’s College of Veterinary Medicine launched a canine sports-medicine program and researchers (including Dr. Steiss) decided to take a closer look at the tail disorder after talking to owners and trainers in the region.

“These trainers were saying, ‘Hey, this is a problem. We see it frequently, and nobody really knows what it is,'” says Dr. Steiss, who had a special interest in muscle disease and was intrigued by the strange injury. Although it seemed uncommon in the dog population as a whole, it sprang up with regularity among Pointers in the area. In one instance, an Alabama kennel discovered that 10 of its 120 adult English Pointers had been affected with limber tail in one morning.