We’ve come so far since those dark days just over a decade ago when virtually all dog training was accomplished through the use of force and compulsion. I know those days well; I was quite skilled at giving collar corrections with choke chains and attained several high-scoring obedience titles with my dogs using those methods. And as a shelter worker responsible for the euthanasia of unwanted dogs for whom we couldn’t find homes, I was convinced that a little pain in the name of training was acceptable and necessary to create well-behaved dogs who would have lifelong loving homes.

In fact, when I enrolled my Australian Kelpie pup in the now-renowned Dr. Ian Dunbar’s first-ever puppy-training classes at our shelter in Marin County, California, I was so sure that using physical corrections in training was the only way to go, that I dropped out of the class after just two sessions; I was convinced he was ruining my dog with training treats!

It was several more years before I crossed over to the positive side of dog training, thanks in large part to my wonderful dog Josie, who gently showed me the error of my ways one day by hiding under the back deck when I brought out her dog training equipment. Her quiet eloquence made me realize, finally, the damage I was doing to our relationship with tools and techniques that relied on the application of pain and intimidation to force her to comply. I threw away the choke chains and began my journey toward a more positive perspective on training.

What Makes Positive Training Different?

Today, in many areas of the country a dog is at least as likely to be enrolled in a class with a trainer who uses positive methods as one who still employs old-fashioned choke chain or prong-collar coercion. As more dog owners and dog trainers see the light, clickers, treat bags, and positive reinforcement replace metal collars, shocks, and dominance theory. Many trainers who still fall back on compulsion tools will at least start with dog-friendlier methods, resorting to force and intimidation only when positive training seems not to work for them. Dogs and humans alike are delighted to discover a kinder, gentler method that still gets results.

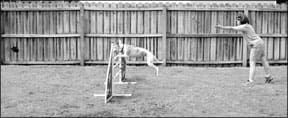

Trainers, behaviorists, and dog owners are realizing that this is more than just a philosophical difference, or a conflict between an ethic that says we should be nice to animals versus a more utilitarian approach to training. While both methods can produce well-trained dogs, the end result is also significantly different. With positive training, the goal is to develop a dog who thinks and works cooperatively with his human as part of a team, rather than a dog who simply obeys commands.

Positive trainers report that dogs trained effectively with coercion are almost universally reluctant to offer behaviors and are less good at problem-solving. Fearing the “corrections” that result when they make mistakes, they seem to learn that the safest course is to do nothing unless and until they’re told to do something.

In sharp contrast, dogs who have been effectively trained with positive methods tend to be masters at offering behaviors. Give them a new training challenge and they almost immediately set about trying to solve the puzzle. In fact, one of the criticisms often voiced by trainers who don’t understand or accept the positive training paradigm is that our dogs are too busy always “throwing” behaviors instead of lying quietly at our feet like “good” dogs. This conflict in perspectives is illustrated graphically by a T-shirt belonging to one of my trainer friends, Katy Malcolm, CPDT, of Canine Character, LLC, in Arlington, Virginia.

“Behave!” proclaims the front of the shirt in bold letters. To the average disciplinarian, “Behave!” means “Sit still; don’t move!” But the back of Katy’s shirt says, “Do lots of stuff!” Positive trainers see the word “Behave!” as an action verb and encourage their dogs to offer lots of behaviors.

Another criticism of positive training is that the dogs are spoiled and out of control because, while the dogs are highly reinforced for doing good stuff, no one ever tells them what not to do. “Dogs,” the critics say, “must know there are consequences for inappropriate behaviors.”

We don’t disagree with this statement. Positive does not mean permissive. We just have different ideas about the necessary nature of the negative consequence. When one is needed, positive trainers are most likely to use “negative punishment” (taking away a good thing), rather than “positive punishment” (the application of a bad thing). As an adjunct to that, we counsel the generous use of management to prevent the dog from practicing (and getting rewarded for) undesirable behaviors.

The result? Since all living things repeat behaviors that are rewarding, and those behaviors that aren’t rewarded extinguish (go away), the combination of negative punishment and management creates a well-trained dog at least as easily as harsh or painful corrections and without the very real potential for relationship damage that is created by the use of physical punishment.

One of the most significant reasons for not using physical punishment or force with dogs is the potential for eliciting or exacerbating aggressive behaviors from them.

This was illustrated by an English Bulldog in a recent episode of the National Geographic Channel’s show, “The Dog Whisperer.” Cesar Millan, the star of the show, spent several hours intimidating the Bulldog on a hot Texas day, in an effort to get the dog to “submit,” until the dog finally inflicted a significant bite to Millan’s hand in a futile attempt at self-defense. Millan brushed the incident aside as insignificant, apparently blissfully unaware that he had provided the dog with the opportunity to successfully practice the undesirable behavior (aggression).

Even if the dog’s reaction falls short of a flesh-shredding defense, the relationship between dog and owner can be significantly damaged as the dog learns to fear or resent the angry, unpredictable responses of his human. Given our odd primate body language and behaviors, we are undoubtedly confusing enough to our canine companions, without adding what to them must seem like completely unprovoked, incomprehensible explosions of violence.

Crossing Over

Increasingly, trainers are entering the profession who learned their craft without an early foundation of coercion training. This is a good thing! However, there are enough old-fashioned trainers around that positive trainers still find themselves working with a fair number of “crossover dogs” those who are convinced that they must not dare offer a behavior for fear of punishment.

It can be frustrating to owners and trainers alike to work through the dog’s conditioned shutdown response to the training environment. Shaping exercises, especially “free-shaping” that reinforces virtually any behavior to start with, are ideal for encouraging a crossover dog to think outside the box. This serves the same purpose for crossover owners and trainers as well! (See “The Shape of Things to Come,” March 2006.)

It takes time to rebuild the trust of a dog who has learned to stay safe by waiting for explicit instructions before proceeding. It’s well worth the effort. The most rewarding and exciting part of training for me is watching the dawning awareness on a dog’s face that he controls the consequences of his behavior, and that he can elicit good stuff from his trainer by offering certain behaviors. We never, ever, experienced that in the “old days.” I used to take “sit” for granted, because if the dog didn’t sit when I asked, I made him do it.

Today, I never get over the thrill of that moment when the dog understands, for the first time, that he can make the clicker “Click!” (and receive a treat) simply by choosing to sit. It keeps training eternally fresh and exciting.

Not Quite Convinced?

So why, given all the available scientific and anecdotal evidence about the success of positive training, do some dog trainers and owners cling stubbornly to the old ways? Because it works for them much of the time? Resistance to change? Fear of the unknown?

It pains me that so many in the U.S. are still so far away from the positive end of the dog-training continuum. The celebrity status of Cesar Millan is evidence that dog owners and trainers are more than willing to buy into the coercion-and-intimidation approach to training, and that the use of force is an ingrained part of our culture.

Old-fashioned methods can work. Decades of well-behaved dogs and the owners who loved them can attest to that. So why should they bother to cross over to the positive side? The short answer is that positive training works, it’s fun, and it does not have the potential to cause stress and physical injury to our dogs through the application of force, pain, and intimidation. It takes the blame away from the dog and puts the responsibility for success where it belongs on human shoulders.

In the old days, if a dog didn’t respond well to coercion we claimed there was something wrong with the dog, and continued to increase the level of force until he finally submitted. If he didn’t submit he was often labeled defective and discarded for a more compliant model. With the positive paradigm, it’s our role as the supposedly more intelligent species to understand our dogs and find a way that works for them rather than forcing them into a one-size-fits-all mold.

The longer answer is that it encourages an entire cultural mindset to move away from aggression and force as a way to achieve goals. The majority of dog owners and trainers who have fun (and success) using positive methods with their dogs come to realize that it works with all creatures, including the human species. They feel better about training and find themselves less likely to get angry with their dogs, understanding that behavior is simply behavior, not some maliciously deliberate attempt on the dog’s part to challenge their authority.

People who use positive methods to affect relationships get nicer. It feels nice to be nice. Children learn to respect and understand other living beings instead of learning to be violent with them.

When training programs founder, positive trainers are more apt to seek new solutions rather than falling back on force and pain, or worse, blaming and possibly discarding the dog for not adapting to our rigid concept of training. Indeed, in the last two decades, during which time positive training has gained a huge following, we’ve made even more advances in our training creativity and our understanding of behavior, canine and otherwise, and have even more positive options, tools, and techniques.

So, why positive? It’s simply the best way to train.

Pat Miller, CPDT, is Whole Dog Journal’s Training Editor.Miller lives in Hagerstown, Maryland, siteof her Peaceable Paws training center. Sheis also the author of The Power of PositiveDog Training and Positive Perspectives:Love Your Dog, Train Your Dog.