Not long ago, I was talking with Jay Weinstein, professional chef and editor of Kitchen & Cook, another one of Belvoir Publications of magazines, at a meeting with our publisher in Florida. Weinstein asked me where I had flown in from. I told him I had attended a pet products show in Chicago, and was touring some dog food factories on the trip, as well. Ugh! Jay protested, his fine dining sensibilities temporarily offended. Why do they have to be called dog food factories? Why can’t they be called dog food kitchens, at least? Or pet nutrition facilities?

Jay has a point but it was my fault that he was aggrieved by my off hand expression. I’m sure none of the pet food company executives who were proud enough of their facilities to invite me to tour them actually call their workplaces dog food factories. While the very phrase dog food historically has been a sort of insult, the industry itself has become increasingly respectable.

Once primarily the repository for waste products from the human food manufacturing industry, pet food production is a fast-growing industry. And, significantly, the tippy-top end of the market, represented by foods that are made with all (or mostly) human-grade ingredients, is the fastest-growing segment of the market. A headline in the November 2006 Petfood Industry magazine announced, The primary market driver in the US continues to be conversion to higher-priced petfoods. We’ve always focused Whole Dog Journal’s attention on the top end of the pet food market the products made with the best-quality ingredients that money could buy. That’s because we strongly believe that products made with the freshest, best-quality, least-processed, most wholesome ingredients are the healthiest foods for dogs, and the ones that are most likely to support glowing health in the dogs who consume them.

288

While our focus pleased the makers of products that we admired manufacturers whose philosophies are in alignment with ours some pet food industry insiders have complained to us that food is more than its ingredients. What did they mean?

Manufacturing Matters

What concerns these particular critics are pet food companies that purchase high-quality ingredients, but use lower-cost, inferior production facilities to manufacture their products.

Conceivably, two different manufacturers could use the exact same ingredients and formula and end up with widely divergent products in terms of cost and quality. Comparison of the foods based solely on the ingredients (such as we do in our annual food reviews) would understandably aggravate the executives who spent a lot more money and time to produce their company’s foods in the cleanest, best-managed, most-inspected facilities available.

A partial list of the potential hazards of poor manufacturing practices include:

- Inattention to quality control standards results in acceptance and use of inferior or unsafe ingredients (i.e., mycotoxin-infected grains, rancid fats or oils, etc.).

- Product quality is inconsistent (i.e., dry foods are not always dried to a standard level of moisture, nutrient levels vary widely in the finished product).

- Product has a higher probability of being contaminated with chemical hazards (pesticides, cleaning agents); pests (insects, rodents, birds, or their feces); foreign objects (such as ingredient packaging, bits of metal or plastic); and biological hazards (bacteria, toxin-producing mold).

- Inadequate testing results in excessive variation of nutrient levels or undetected contamination.

- Product does not contain what its label says it contains (wrong ingredients are used, substitutes are made, measurements are incorrect, ingredients are omitted, or product is mislabelled).

- Problems exist with packaging (faults with seals or seams, packages damaged in storage or transit).

- Poor inventory control means food spends too much of its shelf life in a warehouse before being shipped to retail outlets; may arrive at consumers’ homes at the end of its “best used” by stage.

Unfortunately, while it’s clear that good manufacturing practices matter, it’s impossible for a consumer to determine which pet foods were made well when it’s still difficult just to find out where pet foods are made! And even if you do learn the origin of your dog’s favorite food, there are very few ways to determine a manufacturer’s reliability and competence.

288

What I’ve seen

I’ve now toured nine pet food and pet treat production facilities in seven states. (Note: Since it was expressly not my intention to review or inspect any manufacturing facility to which I was invited, I’m not going to name or locate each facility I toured, or be specific in my descriptions of each site. My interest in each plant was educational, not investigative.)

I’ve witnessed the manufacture of extruded and baked dry dog (and cat) foods, baked “cookie” and “biscuit” type treats, dried treats and chews made from a variety of animal tissues, and canned food. I’ve yet to visit a facility that makes raw frozen diets or dehydrated diets, though I have received invitations and plan to see these foods made as soon as possible.

Interestingly, each facility I’ve toured seemed to be managed with an emphasis on different criteria.

The pride of one dry food plant seemed to be its on-site laboratory complete with a well-educated, full-time dedicated lab staff and its workers, who were retained long-term with larger than average salaries and generous benefits. The manager of that plant explained that his company leadership strongly felt that the longer each employee was retained, the more valuable they became.

At another facility, one that manufactured oven-baked foods and treats, certification and high scores in a variety of quality-control programs seemed to be the management’s primary focus.

At one canned food plant, top-quality ingredients were foremost on the manager’s mind; other aspects of the operation seemed to be hardly considered. I had a similar experience at the smallest extruded food plant I’ve seen so far. The ingredients were top-shelf; the manufacturing process itself seemed comically informal. At another cannery tour, special emphasis was put on the mixing and cooking processes; it appeared that extraordinary resources had been invested in advanced technology to achieve the most consistent results in those areas. The newest dry food plant I toured was similarly equipped with new and advanced computer-based technology for controlling ingredient inventory, mixing, cooking, cooling, coating, and packaging. It was far more impressive than some of the human food manufacturing operations I’ve toured.

288

Size Matters

I haven’t been in any plants operated by the industry giants Nestle Purina, Mars (which, in 2006, purchased Doane Pet Care, the largest maker of private label pet foods), Iams (Proctor & Gamble), Hill’s Pet Nutrition (Colgate Palmolive), and Del Monte. At one point I made a huge effort to gain access to one of these behemoths and got nowhere.

I have interviewed a number of pet food industry executives who spent decades at one or another of the giant companies, who confirmed my guesses of what’s inside the huge plants: Lots of gleaming machinery and floors, and the most inexpensive ingredients available.

This gets to what seems to me to be the most significant trade-off: The bigger a manufacturing plant is (the greater its production capacity), the more likely it is to be impeccably clean and modern. Its products are more likely to be consistent . . . and the less likely it is to use fresh, whole ingredients in its products.

In contrast, in the plants I saw with the smallest operational capacity, lavish attention was paid to the ingredients of the food . . . but the sanitation was not impressive, and equipment for lab testing of the product was not in evidence. Small facilities, especially those with limited production runs (making food just a few days a week, or in extremely small batches), may lack the full-time, well-trained staff needed to produce foods with a consistent level of quality. While I’m unaware of any specific problems arising from the shortcomings I perceived, it’s generally true that smaller production facilities tend to struggle more with product consistency than the “big guys”.

That said, it’s only fair to mention that the most devastating incidents in pet food history, where many dogs died as a result of a problem with food manufacturing, involved moderately large- or very large-volume plants.

Overall Impressions

All in all, I have been impressed with the facilities I’ve seen. As my editorial compatriot noted, “dog food factory” conjures up images of a disgustingly smelly, unclean facility. Only one of the nine plants I’ve toured could possibly meet that description (and probably not for long, as the plant is slated for relocation to a new facility). The plants I’ve toured do smell like dog food but fresh, aromatic dog food, not rancid or putrid. Keeping in mind that the plants I toured invited me to their facilities, and each manufactures high-end foods, using high-quality ingredients, it shouldn’t be a surprise that all of the raw materials I saw (meat, fruit, vegetables, grains, dairy products, and herbs) were uniformly fresh-looking and absolutely of supermarket quality. (One plant owner complained that she has to order twice as many avocados as needed for her product formulations, since her employees eat as many avocados as they use in the pet food!)

288

Most of the “fresh” meats I saw were frozen in big blocks, and are fed into the processing machinery still frozen. The only exception to this was one large facility where the fresh chicken was deeply chilled in huge, hot-tub-sized tubs. Temperature control was maintained in all cases.

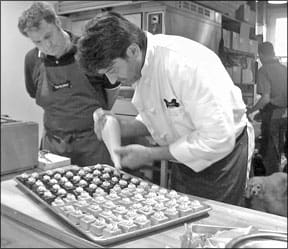

It’s not quite fair to directly compare the two gourmet treat manufacturing facilities I toured with the much higher-volume food and biscuit plants. Suffice to say that Kitchen & Cook would be perfectly comfortable with the mixing, baking, and presentation of the cookies, pretzels, and even cakes produced for dogs in the gourmet treat bakeries.

My next goal is to tour facilities that make human-edible products that can also be fed to dogs. These foods, made in factories (or “kitchens”!) that produce human foods, are increasingly popular. I’m curious to see how (and if) these facilities differ from the pet food plants I’ve seen.

I’ll describe the step-by-step production process for dry and moist foods in our upcoming annual food reviews. The dry food review will appear next month.

Nancy Kerns is Editor of Whole Dog Journal.