[Updated February 5, 2016]

Today, we look back with horror at the time, not so very long ago in historical perspective, that scientists assured us that nonhuman animals didn’t feel pain. We know now how cruelly wrong that was. Next we were told that the thing that differentiated us from the other animals was that humans made and used tools, and other animals didn’t. Dr. Jane Goodall’s work, among others, proved the error of that position. You can find countless examples of various nonhuman animals using (and even creating) tools on Youtube.com! My favorite video clip is of a crow bending a wire into a loop so he can reach into a long tube to hook the handle of a small container of food so he can pull it up and eat the food (you can see the clip for yourself at tinyurl.com/cyaeep).

Okay, so other animals can make and use tools, but certainly they don’t have “human” emotions. Or maybe they do. In fact, it’s pretty species-centric to even call them “human” emotions when they are simply . . . emotions.

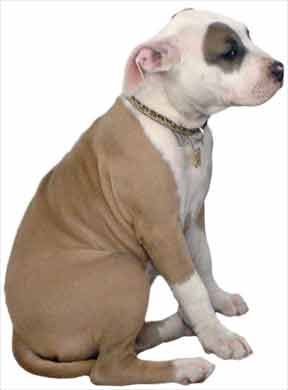

Current research has demonstrated that many species, including our beloved canines, share brain circuitry very similar to the human part of the brain that controls emotion – the amygdala and the periaqueductal grey. While there’s no doubt among most dog lovers that dogs have emotions, this concept is still being discussed in the halls of academia. Some insist that even though animals show emotional behaviors that we can observe, we can’t assume the behaviors mean the animals who display them have emotional feelings. (I don’t know how anyone can think this, but some scientists really do!) Others, such as the esteemed neurobiologist Dr. Jaak Panskepp of Washington State University, argue that if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck – it’s probably a duck!

Given that most of us now accept that many animals in addition to humans have at least some emotional capacity, the last stronghold of science is the vast superiority of human cognition: the ability to think.

There was a time when our species believed that dogs (and other nonhuman animals) possessed very little cognitive potential compared to our own large front-brain ability to ponder the mysteries of the universe. It was believed that the size of the cortex controlled cognitive potential, and since a dog’s cortex is relatively smaller than a human’s, they must possess very little real ability to “think.”

Recent studies, however, have demonstrated that even insects, with their tiny brains, are capable or more complex thought than they’ve ever been given credit for.

Getting Up to Date

According to a growing number of studies, most notable those done by Lars Chittka, Professor of Sensory and Behavioural Ecology at Queen Mary’s Research Centre for Psychology and University of Cambridge colleague Jeremy Niven, some insects can count, categorize objects, even recognize human faces – all with brains the size of pinheads. Instead of contributing to intelligence, big brains might just help support bigger bodies, which have larger muscles to coordinate and more sensory information coming in via the larger body surface.

Only in the past decade has the domestic dog begun to be accepted as a study subject for behavioral research. Brian Hare, assistant professor of evolutionary anthropology at Duke University, opened the Duke Canine Cognition Center in the fall of 2009, the same year Marc Hauser, a cognitive psychologist at Harvard University, opened his own such research lab. Similar facilities are now operating across the U.S. and in Europe.

The results are challenging our past beliefs about canine cognitive abilities. Many dog owners have heard of the studies that demonstrate a dog’s ability to follow a pointed finger.

More recently, in a study conducted by John W. Pilley and Alliston K. Reid, the accomplishments of Chaser, the Border Collie who learned more than a thousand names of objects have generated excitement in the dog world.

Of even greater interest to cognitive scientists is Chaser’s ability to distinguish between the names of objects and cues. She understands that names refer to objects, regardless of the action she is told to perform in relation to those objects. She was asked to either “nose,” “paw,” or “take” one of three toys in an experiment, and could successfully do so.

Even more astounding was the final piece of this study, which concluded that Chaser (and by extrapolation, other dogs) is capable of inferential reasoning by exclusion. That is, she can learn the name of a new object based on the fact that it is the only novel object in a group of objects whose names are all already known by her. Meanwhile, biologist and animal behaviorist Ken Ramirez is currently engaged in eye-opening research that studies a dog’s ability to imitate (copy) another dog’s behavior.

While growing evidence supports a theory of significant cognitive ability in dogs, the last holdout may be metacognition – the “self-awareness” that some tightly hold to be a uniquely human trait. But just like treasured misbeliefs from prior eras, this, too, may fall.

David Smith, PhD, a comparative psychologist at the University at Buffalo who has conducted extensive studies in animal cognition, says there is growing evidence that animals share functional parallels with human conscious metacognition – that is, they may share humans’ ability to reflect upon, monitor or regulate their own states of mind.

We now find it absurd to have ever believed that other animals don’t feel pain; there may well come a time when we also find it absurd to believe that dogs and other nonhuman animals aren’t self-aware.

Let’s Talk About It

Recently, I had the honor of attending (and speaking at!) the 21st conference of the Professional Animal Behavior Associates (PABA), and the theme of the entire conference was “Exploring the Dog’s Mind.” What a delight!

I walked into the lecture hall at the University of Guelph (Ontario), excited to be speaking among such notables as Dr. Andrew Luescher of Purdue University; Dr. Alexandra Horowitz, Barnard College at Columbia University; Dr. Meghan Herron, Ohio State University; Karen Pryor, Karen Pryor Clickertraining; Kathy Sdao, Bright Spot Dog Training; and omigosh, Dr. Jaak Panskepp! I was in heady company. Plus, I hadn’t attended a conference for some time, and I was eagerly looking forward to this one that was focused on cutting-edge concepts in canine cognition – how dogs think. I was not to be disappointed.

Dr. Andrew Luescher

Board-certified veterinary animal behaviorist and director of the Animal Behavior Clinic at Purdue University, Dr. Andrew Luescher emceed the conference, and spoke on “The Psychological Needs of Dogs,” and “Companion Animal Welfare.” Dr. Luescher addressed the now well-known importance of early development, and stressed that “Deficiencies or abnormalities in early development can often not be compensated for, and that behavior/temperament issues based on early deficient development have a poor prognosis.”

While we all know of success stories from people who have rescued and rehabilitated dogs who were either undersocialized or traumatized during their early developmental periods, the greater likelihood is that pups who don’t have the opportunity to develop normally during this period will never be completely normal.

Luescher reminded us that part of proper early development requires puppy-proofing and management. While old-fashioned trainers still assert that a dog has to learn that there are consequences for mistakes in order to be fully trained, Luescher refutes this, saying, “The idea that a puppy has to do the wrong thing to learn what the right thing is, is wrong.” His behaviorally scientific explanation for this is, “If a behavior is successful, others are suppressed.” In other words, if a pup is reinforced for doing desirable behaviors, the undesirable ones don’t happen.

In addressing companion animal welfare, Luescher focused on the unsound practice of always breeding for “more.” We have a tendency in our show ring/breeding culture to always exaggerate characteristics. If a breed is big, make it bigger; if it’s small, breed for smaller. If a nose is long, make it longer; if it’s short, make it shorter.

The fallacy of this approach is that it breeds unsoundnesses into our dogs, such that Bulldogs can’t breathe well; the giant breeds have very short lifespans; and many toy breeds can’t whelp without a Caesarian section.

Dr. Meghan Herron

Board Certified Veterinary Animal Behaviorist Meghan Herron, DVM, head clinician at the Behavioral Medicine Clinic at the Ohio State University College of Veterinary Medicine, spoke about her research project on the effects of confrontational training methods on dogs.

Since we are always alert for scientific verification of our assertions that positive training methods are better, and documented statistically significant studies on training methods are rare, Herron’s study is important for dogs and the people who love them. Notable conclusions from her study included:

-Confrontational techniques increase the likelihood of aggression, especially in dogs

-Few dogs respond aggressively to reward-based training

Herron acknowledges that her study had some limitations (as do all studies): it was a “self-selected” sample of dogs presented at the clinic for behavior problems; the study utilized a limited list of potential behavior interventions; it was a self-reporting study, relying on owner-interpretation of behavior; and it did not study the efficiency of various behavior interventions, only the uses and outcomes.

Herron is planning a future study that will utilize a larger sample size; assess a more general population and a wider variety of methods; conduct a stricter comparison between positive reinforcement and positive punishment; and design a prospective study that follows the behavior of the study-group dogs into the future.

Kathy Sdao

The dynamic speaking style of well-known and highly respected applied animal behaviorist Kathy Sdao, MA, ACAAB, puts her in great demand as a seminar presenter. Early in her career, Sdao trained marine mammals at a research laboratory at the University of Hawaii for the U.S. Navy. Now based in Tacoma, Washington, she’s been training dogs and their people since 1995.

Sdao addressed the often-raised question as to whether old-fashioned coercion training is faster than clicker training. Sdao confirmed that if two trainers were in a contest to see which one could get an untrained dog to place his body flat on the ground faster, the trainer using force would likely win. She also confirmed what any experienced clicker trainer knows: that more valuable long-term goals are without a doubt better served by clicker training than by the use of force and coercion. What sort of goals? Simple and clear communication; motivating the dog to act, interact, and engage with humans; building a relationship of trust between dog and human; and creating an accelerated learning process.

Sdao also presented a session on “Hierarchy Malarkey,” refuting the unfortunate “conventional dominance wisdom” that lingers in the minds of the dog-owning public despite the best efforts of positive trainers and behavior consultants worldwide. (In fact, “anti-dominance theory” was an ongoing thread throughout the conference.)

Sdao presented a slightly different perspective by arguing that even the “Nothing In Life Is Free” protocol promoted by many positive trainers – in which a dog has to earn all good stuff by offering a good manners behavior (such as a sit) first – is based in outdated “alpha” theory. Life with dogs isn’t all about who is trying to overthrow the pack leader. Sdao suggests that this perspective needs to be replaced by an approach that embraces cooperation and affection.

Dr. Alexandra Horowitz

Alexandra Horowitz, MS, PhD, is an assistant professor at Barnard College in New York. She has specialized in animal cognition, and has conducted more than 10 years of research on dogs. We anticipate that her current research and studies will provide much needed and credible information for those of us who insist that anthropomorphism is no longer a dirty word.

Anthropomorphism is the use of human characteristics to describe nonhuman animals. According to a 2008 survey of 337 dog owners, most owners believe that their dogs feel sadness, joy, surprise, and fear. There was less of a consensus on other “secondary” emotions that some attributed to their dogs:

-Embarrassment 30%

-Shame 51%

-Disgust 34%

-Guilt 74%

-Empathy 64%

-Pride 58%

-Grief 49%

-Jealousy/fairness 81%

Most dog training and behavior professionals agree that the behavior owners commonly describe as “guilt” is actually simply appeasement behavior offered in response to human body language. Horowitz designed a study to test the guilty look phenomenon, by having the owner leave her dog in the room with a piece of food, after telling the dog not to eat it. Sometimes Horowitz left the food in view, sometimes the dog ate it and sometimes not, and sometimes she removed it and told the owner the dog ate it. If the food was gone, the owner scolded the dog. Horowitz’s findings were:

1) Guilt did not change the rate of the guilty look. The rate of measured “guilty” behaviors was similar whether the dog was “guilty” (ate the treat) or “not guilty” (didn’t eat the treat).

2) Owner behavior did change the rate of the guilty look. The rate of guilty behavior was significantly higher when the dog was scolded than when the dog was greeted, regardless of whether or not it had eaten the treat.

3) Dogs showed the most guilty behavior when they were “not guilty” but punished. Scolding led to higher rates of guilty look behavior when the dog had not eaten the treat than when the dog had eaten it.

It’s always nice when we have science to back up some of our dearly held training and behavior beliefs, like the one that says “dogs are offering appeasement behaviors, not showing guilt, when their owners come home to a soiled carpet or overturned garbage can.” Horowitz’s current and ongoing study on whether dogs perceive “fairness” is likely to have equally interesting results.

Horowitz’s second intriguing presentation was entitled “What Is It Like to Be a Dog?” She reminded us that because of dogs’ incredible sense of smell, their world arrives on the air, and they tell time differently than we do. If the wind is right, they can smell the future – that which is in front of them that they will soon encounter. When they are smelling the ground, or the neighborhood pee-post, they are actually smelling the past – that which has come here before.

For more on her perspectives on how dogs perceive the world, you can read Dr. Horowitz’s fascinating book, Inside of a Dog; What Dogs See, Smell and Know, published in 2009.

Karen Pryor

A behavioral biologist with an international reputation in the fields of marine mammal biology and behavioral psychology – as well as one of the founders of clicker training – Karen Pryor spoke on “creativity and the animal mind.”

According to Pryor, being creative implies novelty: producing something new and different. She referenced Dr. Jaak Panskepp’s work with the seeking system – that which motivates an animal to go out and have fun. Seeking behavior is not driven by survival; it happens only when the animal is already comfortable.

In humans, seeking includes things like window-shopping, doing puzzles and playing games, and Web surfing. In nonhuman animals, seeking may include exploring new terrain and showing curiosity about new objects and other living things.

Pryor suggests dog training can capitalize on seeking and creativity by clicking and treating exploration, chance-taking, persistence, and novel behavior. Because your dog can’t be wrong (you’ve not asked for a behavior) there’s no association with failure, so the dog has fun. The more behaviors you capture or shape, the more innovations your dog is capable of inventing. The well-known “101 things to do with a prop” is a great example of asking your dog to innovate.

Dr. Jaak Panskepp

Jaak Panskepp, PhD, is the Baily Endowed Chair of Animal Well-Being Science for the department of Veterinary and Comparative Anatomy, Pharmacology, and Physiology at Washington State University’s College of Veterinary Medicine, and Emeritus Professor of the department of Psychology at Bowling Green State University.

Dr. Panskepp has been described as being 20 years ahead of his time. His work on animal emotions and the brain’s “seeking system” – fueled by the neurotransmitter dopamine, which promotes states of eagerness and directed purpose – takes behavior science to the cutting edge. Panskepp describes the seeking system as, “the mammalian motivational engine that each day gets us out of the bed, or den, or hole to venture forth into the world.”

Panskepp argues convincingly that not only do nonhuman animals possess emotions, but they also possess what behavioral science calls “mind.” In refuting the “lack of proof” argument in the “do dogs have emotions?” discussion, he asserts that scientists deal with “weight of evidence,” not “proof.” The weight of evidence overwhelmingly indicates that animals have feelings. In fact, the evidence is so strong that animals have emotional feelings (not just emotional behaviors), that he says it’s a done deal, case closed (although the argument still rages in academic circles).

The question of “mind,” or metacognition, may be more open to debate. Mind has three fundamental properties:

Subjectivity – Experiences “self” in the real world.

Volition – Deliberate behavior; intentionality, seeking, desire, interest, and expectancy.

Consciousness – The capacity for self- consciousness, includes questions about “theory of mind” in nonhuman animals; whether animals are capable of attributing mental states to others.

Hard scientific evidence of canine mind is harder to come by than canine emotion. The same brain circuits exist in humans and many other animals, suggesting that mind may exist for them. Panskepp argues that animals do possess at least some degree of mind, and that the answer to this question will become clearer with continued neurobiological and cognitive study. Indeed, some aspects of canine mind seem inarguable. Does anyone doubt that dogs have volition? If it walks like a duck . . .

Pat Miller

I also spoke at the conference, on two topics dear to my heart: shelter assessments and modifying dog-dog reactivity. I presented video and an applied science discussion from my work in these areas (citing Kelley Bollen’s 2007 study on shelter assessments).

Mostly I watched, listened, and marveled at the depth and breadth of information offered at the conference, and at the evidence of how far we have come in the world of dog training and behavior. Not so long ago, few, if any, dog trainers had a clue about the science of behavior and learning, nor a working knowledge of operant and classical conditioning, theory of mind, metacognition, creativity, shaping, or any of the other concepts presented at this conference.

We may still have much to learn about what our dogs are thinking, but we have come a long, long way from those dark days when animals supposedly didn’t feel pain.

Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, CDBC, is WDJ’s Training Editor. She lives in Fairplay, Maryland, site of her Peaceable Paws training center, where she offers dog training classes and courses for trainers.