Download the Full March 2014 Issue PDF

Puppy Shots

We have long advised puppy owners to have their vet run a “vaccine titer test” a few weeks after the series of “puppy shots” were completed. In our view, adopted from that of the canine vaccination experts we most respect (Ron Schultz, PhD, who has been involved in the development and testing of most of the vaccines used on dogs in this country; and W. Jean Dodds, DVM, a veterinarian who has extensively studied and written about canine vaccines), only a positive vaccine titer test can tell you whether the puppy’s immune system responded to the vaccines in the manner that was intended.

A brief refresher: Puppies are born with antibodies from their mothers still circulating in their bodies. (Some of these they gained from the blood they shared with their mothers via the umbilical cord, and some from the colostrum that they drank in the first couple of days after they were born). These antibodies “fade” (disappear) at a variable point – from a few weeks to as much as six months after the birth of the puppy.

A vaccination is a weakened, modified, or killed strain of disease antigen – the substance that could otherwise cause disease. We administer disease antigens to a dog or puppy in order to “teach” their immune systems to recognize them as invaders, so they produce antibodies that are specifically designed to recognize and neutralize those antigens. If the animals are later exposed to one of these disease antigens in a live, virulent state, the antibodies will recognize the antigens and annihilate them before they can infect and sicken the dog.

When his mother’s antibodies are circulating in a puppy’s bloodstream, and we vaccinate him (with disease antigens), the mother’s antibodies recognize those antigens and neutralize them. When this occurs, the puppy does not develop his own antibodies (protection) from the vaccines he was given. This mechanism is known as “maternal interference” – the mother’s antibodies have interfered with the vaccine. That’s why we vaccinate the puppy again and again: because until this maternal interference fades, the puppy’s own body can’t begin to recognize the disease antigens in the vaccines and develop his own antibodies to those diseases. Pups are vaccinated two to three weeks apart, in an effort to minimize any potential gap in coverage (between the fading of the maternal immunity, and a vaccination and resulting development of the pup’s own immunity).

On four separate occasions, my son’s new pup, Cole, was vaccinated at the shelter from which he was adopted. His age was estimated to be six months – the time when a puppy’s maternal interference is almost always gone – when I took Cole in for a vaccine titer test, to make sure he was what’s called fully “immunized,” not just “fully vaccinated.” In other words, to make sure he had developed his own antibodies to the diseases for which he was vaccinated.

Guess what? He hadn’t. The result of Cole’s titer test for distemper was negative. We assumed (like almost everyone does) that after all those puppy shots, he was protected, but if he had happened to come into contact with a dog or pup who had been infected with distemper, or had been someplace an infected dog had recently been, Cole could have contracted this often fatal disease.

Thanks to our knowledge, gleaned from the experts who inform WDJ, we found out that he was unprotected, so we vaccinated Cole again. We’ll run another titer test in about three weeks, and keep him away from dog parks and sidewalks until we have the results. And I will discuss vaccinations, titer tests, and Cole’s situation at greater length in the April issue.

Keeping Your Dog’s Feet Healthy

My young Bouvier, Atle, has the triple threat of dog nails: black, stout, and surrounded by lots of hair. Regular nail trimming is not a task I relish, yet the importance of trimming nails can’t be underestimated. Left untended, long nails can splinter or break off, affect your dog’s gait, and cause orthopedic issues and pain. Although ultra-critical for performance dogs, proper foot care is required for the health and well-being of all dogs – couch potato or agility star.

Your dog’s feet are full of nerves that help him with proprioception; that is, an understanding of where his body is in space and relative to the ground (i.e., which end is up). When your dog’s nails are too long, messages to his brain get scrambled, altering his gait and posture. That’s anathema to integrative veterinarian Julie Buzby, DVM, CAVCA, CVA, founder of Dr. Buzby’s ToeGrips, a company that makes a traction aid to help elderly and other mobility-impaired dogs stop slipping on slick floors.

Dr. Buzby is passionate about canine nail care and describes the postural changes caused by long nails: “A dog with long toenails can’t stand with legs perpendicular to the ground. Rather, he compensates by adopting the ‘goat on a rock’ stance, where his forelegs are ‘behind’ perpendicular and his hind legs must come under him to prevent him from tipping forward.”

Dr. Buzby regularly sees dogs for orthopedic issues. Her exams start from the ground and work up; after a nose-to-tail physical exam, typically a nail trim is the first “treatment” on her list – even before chiropractic care or acupuncture. She recently saw a Dachshund who presented for lameness. His nails were long enough to deform the way his toes contacted the ground, altering his posture and gait.

I’m a sports-medicine junkie, so the idea that regular nail trimming benefits a dog’s gait and posture is enough of a “carrot” to get me on board. Those who need a “stick” to motivate them to maintain their dogs’ nails should consider the specter of broken nails (and the veterinary visits to treat them), which are prevalent in dogs with long nails.

“This is a fairly common problem in veterinary medicine and it’s gruesome to treat – painful for the dog and bloody,” says Dr. Buzby. “There is no conservative way to treat this injury.” Typically that means cutting the nail short at the nail bed by transecting the nail to remove the entire thing. She goes on to say, “Sadly, I can’t remember once in 17 years when this happened in a dog with short nails.”

Nails on the Floorboards

It’s not often that we encounter a Dr. Buzby who will tell us, flat out, that our dogs’ nails need trimming; the responsibility to monitor this is ours. There are a few telltale signs to help you know when it’s time to trim:

Your dog’s nails touch the floor when she is standing.

When your dog walks on surfaces such as hardwood or tile flooring, you can hear clicking.

If you hold up a paw and look at it in profile, the nail extends past the pad for that toe.

Though we’re often told that nails should be trimmed monthly, in fact, they should be trimmed weekly – two weeks at the outside – for best results. Some folks even opt for twice-weekly trimmings.

Front nails seem to wear less quickly than rear, and don’t forget the dewclaws if your dog has them!

Don’t Cut That Quick

Much of the hullabaloo about nail trimming revolves around the dreaded “quick.” This is the center of the nail where nerve and nail blood supply sit. Cutting the quick – as can happen accidently during nail trims – draws blood and can temporarily hurt.

In light-colored nails, the pink quick can often be seen from the top and sides of the nail, whereas in black nails, the quick is not visible from that perspective. To best see the start of the quick, Dr. Buzby recommends looking at the cross section of the nail (front/underneath) that’s visible once the first cut is made. In white nails, the start of the quick is white or pink, while in black nails, it’s grey or black. If you take off very thin slices and examine the nail after each slice, you should be able to avoid cutting into the quick.

Regular nail trimming at tighter intervals is said to help the quick recede, making it possible to trim nails shorter over time. Despite this conventional wisdom, Dr. Buzby, who uses clippers, does not see that happen; an informal poll of a few of her colleagues leads her to believe that most people who are able to get the quicks to recede use a rotary tool, and trim frequently.

Tools and Technique for Trimming Dog Nails

The most popular and most recommended tools are scissor-style clippers or a rotary tool/nail grinder (i.e., a Dremel). Dr. Buzby likes the control she gets with her Miller’s Forge nail trimmers, the same argument made by rotary-tool fans. She would “never use a guillotine-style trimmer,” a sentiment echoed by my dog Atle’s groomer, Angela Duckett-Smutney, who says the guillotine trimmers are harder to finesse. If your dog is less than perfectly cooperative and patient, it can be difficult to “thread” each toenail into the hole of the guillotine in order to cut it.

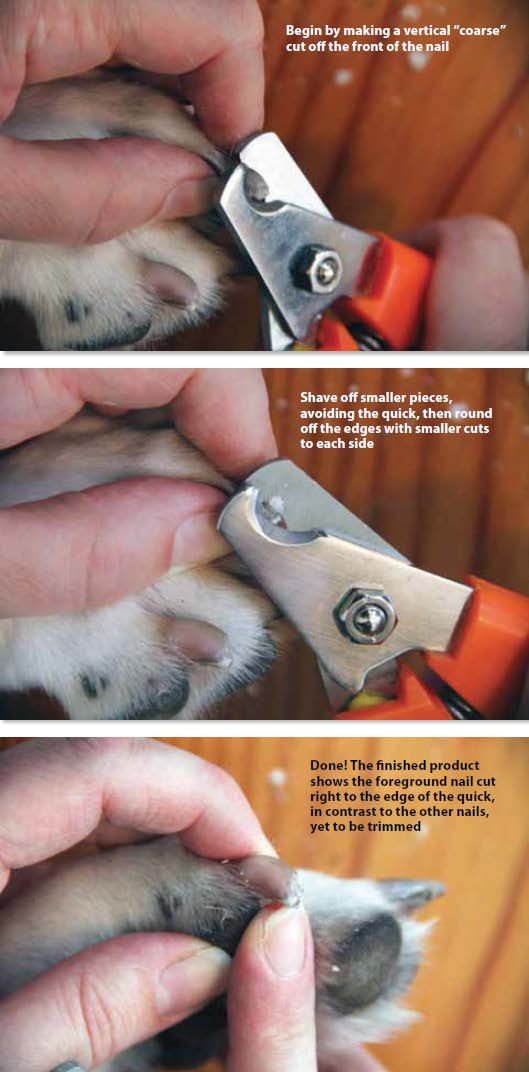

The following is Dr. Buzby’s technique for trimming using nail clippers:

1. Make a coarse cut off the top/front of the nail to remove obvious length. “The angle is very vertical and that is my trade secret!” This is in contrast to a 45-degree angle that is commonly recommended. Since the quick may not be visible on a black nail, the first cut is somewhat blind; err on the conservative side for this coarse cut on dark nails, taking off just the tip to start.

2. When trimming dark nails, many people remove only the tip, but don’t stop there! White or black nail, shave off small slivers until you can see that the quick is close to the cut surface.

3. Round off the sides/corners using smaller cuts. It’s safe to remove the sharp edges on either side of the nail without affecting the quick, since it runs in the center of the nail.

Some individuals prefer to take length off first using clippers, then finish the job with a nail grinder. Whether clipping first or not, Atle’s groomer likes to use a coarse 60 grit wheel and recommends a rotary tool that has significant voltage. She prefers to hold the rotary tool close to the wheel, using short strokes from the bottom of the nail up. She starts with one stroke up the middle, then one on each side at a 45 degree angle, holding each toe individually.

Beware of the hair with long-haired dogs! To keep it from getting wound up by the rotary tool, one recommended technique is to push the dog’s nails through a cheap pair of pantyhose prior to trimming. For these dogs, too, it’s imperative to trim the hair between the pads, as well as any excess hair growing around the edges of the paw.

Helpful Hints for Nail Trimming

The following are a few tips that can help with proper nail-trimming:

– In addition to our dread of cutting the quick, many dogs aren’t keen on having their paws handled, and/or aren’t thrilled about the noises associated with nail-trimming tools. See “Positive Pedi-Pedi’s” (WDJ August 2012) for tips on getting your dog desensitized to a nail-trimming routine.

– There doesn’t seem to be one favored position in which to place your dog for nail trimming; experiment and see what works best for both of you.

– Before you start a session, get out your Kwik Stop or other styptic powder – flour, cornstarch, and a bar of soap are all said to work in a pinch – to have by your side should you cut the quick. If you draw blood, don’t overreact! Quietly and quickly apply pressure and a pinch of powder to the nail. Your dog will be okay!

– Be mindful of how much pressure you’re applying to your dog’s toes. Hold her paw only as tightly as you need to – too hard and it hurts!

To keep yourself and others safe, introduce your dog to a muzzle to wear during nail trims if she tends to go on the offensive.

– One other novel approach to consider: train your dog to “do” her own nails by scratching them on a sandpaper-like surface.

If you’re still uncomfortable cutting your dog’s nails, ask your vet or groomer to show you how. Dr. Buzby notes, “It’s critical to keep this a positive experience for the dog. In my first practice, we educated clients on the importance of nail care and the veterinary technicians did a complimentary nail-trimming tutorial as part of every new puppy/kitten office visit. Veterinarians should be tackling both issues [why and how] through client education.”

How to Properly Examine Your Dog

Does your puppy or adult dog squirm when you check his ears? Squeal as you touch his toes? Or slink away when you bring out the brush? If so, you are not alone. A very few easygoing dogs seem to have been born enjoying all types of touch and handling. But most puppies and dogs need a little help when it comes to sensitive areas and intrusive touch. Is it really possible to help a dog learn to tolerate all types of handling? Absolutely! And, with a little special attention and training, your dog may even come to love the same types of touch that used to make him squirm, squeal, or slink away.

Handling Exercises: Start Them Young

Handling exercises are an important part of early socialization. One of the best ways to prevent problems with handling later in life is to make handling exercises a priority with your pup. Prior to 12 weeks of age, pairing handling and touch with pleasant experiences – say, a tasty treat – can help condition the pup to enjoy all types of touch.

For example, you may want to gently touch your puppy’s ear, and then give her a great treat. After she is happy and comfortable with you gently touching her ear, then you can lift the ear, and once again give the pup a treat. When she is comfortable with lifting the ear, you can gently rub the ear and offer a treat. This pairing of touching and treats should be repeated with puppy’s paws, tail, head, muzzle, mouth, back, belly, legs, neck, and collar. Be sure to have other members of your family and friends help with touching exercises, too. The positive associations created in puppyhood can last throughout their lives.

Handling Exercises for Adult dogs

Handling exercises are just as important for older pups, as well as adolescent and adult dogs. You can begin with conditioning your adult dog to all types of touch and handling, just as you would a puppy. Depending on the dog and his previous socialization and experiences, you may not need to continue pairing all types of touch with treats, but you will want to keep it up with any sensitive areas. You might skip the treats for any handling that your dog is happy about, such as head pats and belly rubs. But if your dog doesn’t really enjoy having her paws held, for example, frequent pairing of gentle paw holding with treats can help her to accept it when it is really needed.

If you have lived with an adult dog for a while, you are likely aware of what he or she does and doesn’t like in the way of touching and handling. But if you have an adolescent or adult dog that is new to you, use caution as you discover how she enjoys being touched, and what areas may be sensitive. Some dogs may have had uncomfortable, painful, or frightening experiences with handling. Be sure to respect your dog’s sensitive spots until you’ve had the opportunity to counter-condition handling for those areas.

Assessing Your Dog

How do you know your dog doesn’t like to be touched in certain places or is uncomfortable with handling? Of course it is obvious if a puppy or dog expresses a strong objection by growling or by trying to get away. If your dog responds with such negative reactions, you may want to get the help of a professional trainer or behavior specialist to work through handling issues.

However, dogs also express their discomfort in other less obvious ways. Here are a few of the ways a puppy or dog may show discomfort:

– Wiggling, squiggling, or jumping around in a playful manner

– Licking your hands or arms

– Moving away when given the chance

– Repositioning herself to make it more difficult for you to touch her, for example, turning away from you

– Becoming tense

– Putting a chin on or gently mouthing your arm

– Refusing to look in your direction

– How can you tell if a dog is truly comfortable and happy about the way you are touching her?

– Her body is soft and without tension

– She makes a connection, often by looking at you with soft, blinky eyes

– She may gently lean into your handling

For the types of handling we do every day, such as petting, grooming, toweling, quick checks for fleas or burrs, both you and your dog will be happier if your dog truly enjoys the activities. For other types of handling, simple acceptance may be enough. For example, I doubt many dogs actually enjoy intrusive touching such as opening their mouths or having drops put in their eyes, but they can learn to be cooperative and calm and, more importantly, not frightened or threatened by the experience.

While conditioning your dog to touch and counter-conditioning sensitive areas are crucial to low-stress handling, training a set of specific skills to help your dog understand the tasks is equally important. Your dog’s ability to perform the following behaviors can significantly reduce her stress and assist with daily handling and grooming, as well as professional grooming and vet exams.

– Sit, down, stand. As part of basic training, most of us teach our dogs to hold certain positions. Sit and down are the most common. For grooming and vet visits, adding a stand is equally helpful. For comfortable handling, teaching your dog each of these behaviors to fluency (meaning the dog can do them anywhere, anytime, with most types of distractions) is very helpful.

– Lie on your side. As a variation of the down, lie on your side (sometimes called “lie flat” or “relax”) is another position that will come in handy for grooming and exams. As with the sit, down, and stand, building fluency is important with this position. Some dogs are reluctant to lie on their sides when they are in unfamiliar places or around unfamiliar people because this is a vulnerable position. Start by practicing in a variety of places that feel safe to your dog and then gradually extend the practice to other places. This will help build your dog’s trust.

– Still. Still is a variation of a stay exercise. Stay is an exercise in which the dog holds her body in a specific position, such as sit, down, stand, or lie flat. However, most of us train stay with the goal of the handler moving away from the dog. The “still” is similar in that the dog needs to hold her body in one position. However, rather than staying in a position while people move away, the dog must stay in one position even when people are touching the dog. Some people successfully use the “stay” cue for both staying at a distance and staying still for touch. You may choose to build onto your stay cue or use a different cue for the still behavior.

– Holding the muzzle. Teach your dog that your hand around his nose and mouth is no big deal. Start by holding your fingers in a C position. With your other hand, hold a treat behind the C so that your dog will move his head into the C to get to the treat. Practice several times, until your dog is happily pushing his muzzle into the C for treats. Then gradually add some gentle pressure on the muzzle. Slowly add more gentle pressure until your dog is comfortable with your hand holding his nose and mouth. This is a similar technique to conditioning your dog to a physical muzzle, which is also a great idea when preparing your dog for vet visits and emergency situations.

– Chin on hand. You can teach a dog to rest his head on your hand and hold the position. Start by holding your hand out flat in front of your dog’s muzzle and place a treat near your wrist as a lure. Your dog’s chin will move over your palm to get the treat. After the dog gets the idea of moving the chin onto the palm of the hand, I switch from luring to shaping. At first, your dog’s chin may just touch the hand, but you can gradually reward longer and longer holds. I like to teach the dog to hold his chin on my hand until I give a release cue such as “Okay!”

– Give me a paw. Similar to the trick “shake,” this behavior teaches the dog to put her paw into your hand. Unlike the shake behavior, “give me a paw” will also teach your dog to hold the paw in your hand until she is given a release cue such as “Okay!” If your dog offers pawing behaviors, it is generally pretty easy to capture this. Other ways to get the dog to offer the behavior is through shaping it or physically prompting by gently picking up the paw and putting it into your hand.

– Targeting. Targeting behaviors can be particularly helpful in grooming and handling as they can be a terrific way to move your dog without having to manhandle him. For example, you can teach your dog to “hand target,” in which your dog touches your hand with his nose. By moving your hand, and having your dog follow to touch your hand with his nose, you can easily turn your dog around or move him from a down to a stand.

An “eye target” teaches your dog to follow a target with his eyes or head. For example, you can teach him to follow your finger or a pen with his eyes. This is terrific to help a dog turn his head slightly for putting in eye drops or checking ears.

There are many additional behaviors that you might find helpful for your dog. Getting on and off a table for grooming is just one example, and you may be able to think of many more. With some of these behaviors in place, handling, grooming. and vet exams all become much easier and less stressful. Plus, your dog will have the opportunity to earn rewards in the process, which may build more enthusiasm for handling games.

Teach Your Dog Restraint, Too

Sometimes we will not be able to ask our dogs to perform a simple behavior when we need to touch or handle them. Sometimes a situation will override early puppy socialization and handling practice. Perhaps the dog is sick or in pain or too upset to be able to stand still or hold his head up in your hand. In these situations, you may need to physically restrain your dog. Helping your dog understand and accept restraint is another critical skill. Training restraint skills will help if you need to take care of a sick or injured dog, and it will lessen your dog’s trauma as well.

Teaching restraint is fairly straightforward. As with all types of touch and handling, you begin where your dog is comfortable and gradually build her acceptance. Start with gentle motions toward restraint, for example moving your arm around your dog’s body without touching, giving a great treat, and then moving away.

If you start at a place your dog is comfortable and pair the touch with great treats, your dog will soon be okay with gentle holding. Gradual is the key here, making sure your dog is not just accepting but fully comfortable at each step. Slowly add in more pressure until you are actually holding your dog firmly, and then gradually build up the length of time you hold your dog. Taking this slowly and building trust as you go will pay off big time if you have to restrain your dog in an emergency.

Practice restraining your dog from the side first (this is easiest for most dogs) with your one arm across the back and under the belly and the other arm around the chest with a hand resting near the dog’s head. Other restraint positions to practice are holding your dog while he is sitting and you are kneeling behind, and holding your dog while he is lying flat. Most dog first-aid books have good illustrations showing how to restrain your dog. You can also ask your vet to show you the most effective positions.

Conditioning handling, teaching skills for grooming and exams, and helping your dog become comfortable with restraint are all part of helping him accept the daily handling and occasional invasive touching he will endure throughout his life. As you practice, keeping each step within your dog’s comfort zone and gradually building skills, you will also teach your dog to trust you. He will learn that when you put your hands on him, even in ways that are not always comfortable, you have his best interests at heart.

For some dogs, this process will be a breeze and they will learn these skills as a matter of course or through your daily activities. Tooth brushing may help him become comfortable with mouth handling. Regular grooming such as brushing his coat can teach him to love head-to-toe touching. But for other dogs, those who may be more sensitive, uncomfortable, or fearful, the conditioning and training may take some extra time. In the long run, the effort you put in will be well worth it for a dog who is comfortable, accepting, and trusting around touch.

Mardi Richmond is a dog trainer and writer living in Santa Cruz, CA, with her wife and her dog Chance. A formerly feral dog, Chance challenged Mardi when it came to handling skills, but today Chance loves all types of touching, handling, and restraint.

Preventing and Treating Kennel Cough

You’re not likely to forget it if you’ve heard it even once: the half-cough, half-choke – sort of like a Canada goose in need of a Ricola lozenge – that signals your dog has come down with kennel cough.

As canine illnesses go, kennel cough has something of a split personality. Usually, it’s “self-limiting,” which means affected dogs generally recover without any interventions whatsoever, leaving the victim none the worse for wear. But every so often, a dog develops serious complications, necessitating hospitalization and extreme measures. Given that, plus the condition’s highly contagious nature, means that most boarding facilities and even veterinarians sometimes treat it with the kind of alarm usually reserved for an ebola outbreak.

Kennel cough is a generic name for a group of pathogens that produce a contagious upper-respiratory infection in dogs. Sometimes referred to as bordetella (one of the bacteria that can cause it), kennel cough is also called canine infectious respiratory disease (CIRD) as well as canine infectious tracheobronchitis. The abundance of names reflects the fact that kennel cough is really a loosely defined confederacy of viruses as well as bacteria, any of which can produce a cough that lasts from several days to weeks – and sometimes much longer, if complications such as pneumonia arise.

Kennel cough is spread through respiratory secretions, and since few dogs have learned the kindergarten trick of sneezing into the inside of their elbows, it can spread widely and quickly. As its name suggests, places where large numbers of dogs congregate can be a hotbed for spreading the disease, from boarding kennels to dog runs. Most dogs show symptoms within three to 10 days of exposure. In addition to the trademark gagging cough, infected dogs may exhibit sneezing, nasal discharge, and mild lethargy. Healthy adult dogs generally don’t otherwise act sick or stop eating, and likely will continue to play and be active, though physical exertion may trigger more hacking episodes.

In dogs who are very young, very old, highly stressed (for example, in a shelter), or immunocompromised, or who have an underlying condition, kennel cough can advance to the lower-respiratory tract and cause pneumonia, which is life threatening.

If this sounds like a wide range of symptoms, it may be because the illness actually is a range of illnesses, and caused by a variety of infectious organisms, bacterial and viral. (For the difference between kennel cough and canine influenza, as well as the newly identified circovirus, see sidebar.)

When she was a veterinary student more than 35 years ago, holistic veterinarian Christina Chambreau of Sparks, Maryland, did an externship at the National Institutes of Health’s foxhound breeding colony.

“My job for the summer was to do throat cultures on every coughing dog – and lots of them were coughing,” she remembers. “And every dog I cultured had a different combination of bacteria.”

At the same time, Chambreau worked part-time at a number of different veterinary clinics. “Each one had a completely different conventional treatment protocol – one used Prednisone, another used antibiotics, another said, ‘They’ll just get better.’ When you see multiple treatment protocols like that, it means none of them are ideal.”

Is it any wonder this condition is called the kennel cough complex?

Kennel Cough Vaccinations

For many conventional veterinarians, the reflexive answer to preventing kennel cough is to vaccinate for it.

Holistic veterinarian Marcie Fallek, who practices in both New York City and Fairfield, Connecticut, is not a fan of the vaccine, pointing out that it is short-lived and may not be adequately protective, as there is no way to cover all the pathogens that can cause kennel cough.

“It seems to cause disease more than prevent it,” she says, adding that facilities that insist on vaccinating new boarders on site are operating largely on reflex – and fear. And in reality, they aren’t doing a thing to protect their other clients.

“It takes several days, if not a week, for the kennel cough vaccine to be effective,” she explains. “So when you give it on the spot like that, it doesn’t protect the other dogs. If it’s going to give any protection, which is minimal, it’s only going to be the animal that receives it.”

Using this logic, some owners have persuaded boarding and day-care facilities to accept a signed waiver in lieu of a vaccine, agreeing not to hold them responsible should their dog contract the disease.

Veterinarian Jean Dodds of Garden Grove, California, says she “rarely” recommends vaccinating for kennel cough, because generally speaking kennel cough is “not a serious problem and the vaccines are not 100 percent efficacious.” But if an owner does decide to vaccinate, she does not recommend using the injectable form; instead, she recommends the intranasal vaccine, which is squirted up the dog’s nose, or the oral form, which is taken by mouth.

Intranasal vaccines for bordetella activate interferon, a pathogen-fighting protein, in the dog’s body, an action that does not result from injectable forms of the vaccine. “The interferon also helps cross-protect against other respiratory organisms,” says Dr. Dodds.

If you want to or need to vaccinate your dog for bordetella, it might make the most sense to ask your veterinarian for the intranasal bordetella vaccine that also contains a vaccine for CAV-2, a strain of canine adenovirus that affects the respiratory tract. A dog who is immunized against that form of adenovirus is also protected against the far more serious CAV-1, or infectious canine hepatitis, which can be life threatening. This might be unexpectedly welcome news to those who use minimal vaccination protocols that do not include canine hepatitis (including the popular one recommended by Dr. Dodds).

Dr. Dodds notes that, as with every vaccine, there are some dogs who react adversely to the kennel-cough vaccine, especially those with “a hypersensitivity-like response” in which the body responds to an immune challenge so severely that it can be life threatening. If your dog has had an adverse reaction to a kennel-cough vaccine, he should not be given any more of those vaccines for any reason.

For her part, Dr. Fallek recommends using a kennel-cough nosode, a homeopathic remedy that contains the energetic imprint of the disorder; while sometimes referred to as “homeopathic vaccines,” nosodes work differently, rebalancing the body rather than prompting it to mount an immunological attack. “Kennel-cough nosodes are not 100 percent protective, but neither are vaccines,” she points out. Dr. Fallek recommends that those who wish to use the nosode to protect a dog who will be in a high-risk environment start dosing the dog several days before the expected risk, giving the remedy once or twice a day with a 30C potency for a maximum of five days.

When it comes to preventing kennel cough, the best defense is, well, a good defense.

“The bottom line is, the healthier you can get your dog, the better,” Dr. Chambreau says. “You want to build the immune system so she fights it off herself.”

The basic building blocks of good health are just that – basic. Make sure your dog receives the best-quality food and water possible. Avoid and limit exposure to toxins. And pay attention to the early-warning signs that the body gives when it is beginning to weaken, but before disease manifests.

“These are little things your vet won’t think are wrong,” Dr. Chambreau says, including goopy discharge that accumulates in the corners of the eye, slight waxiness in the ears, a little red line in the gums, minor behavioral problems, and a slight overall odor that necessitates baths every couple of weeks. She recommends keeping a daily journal so you can see patterns in your dog’s well-being emerge over time.

“Any holistic treatment that builds the immune system will usually take care of kennel cough,” adds Dr. Chambreau, who is a staunch believer in what she calls “R&R” – a flower essence remedy called Rescue Remedy and reiki, a healing “life force energy” practice. “You take one course in how to do reiki, and you can start offering it to your dogs every day on a regular basis,” says Dr. Chambreau. And while Rescue Remedy and flower essences in general won’t cure kennel cough or any other disease, many dog owners report that these gentle plant distillations can center emotions and help alleviate anxiety or distress about kennel cough, as much for you as your dog!

Another thing you can add to your preventive toolbox is the thymus thump. During the early part of a dog’s life, the thymus programs the T-cells that are so central to the functioning of the immune system. “By tapping the thymus, you reactivate it,” Dr. Chambreau explains.

To find your dog’s thymus, run your hand down her throat, and below the throat feel for the firm, bony protuberance that is the sternum. Gently thump that area with your hand several times a day, or whenever you remember.

Quite an array of supplements, herbs, and tonics are reputed to help strengthen the immune system; the most commonly cited include coconut oil, apple cider vinegar, aloe vera juice, and whole food supplements.

Melissa Oloff of Canterbury, Connecticut, keeps her Ridgeback Coco on an immune-boosting regimen of Vitamin C and probiotics daily, as well as an echinacea capsule several times a week. When the doggie daycare that Coco attends had an outbreak of kennel cough, Oloff increased the frequency of administering echinacea, giving her dog a dose every day during the week when Coco was exposed. “She was fine, no symptoms,” Oloff says. “The kennel had to send home 50 percent of their dogs.”

Kennel Cough Treatment Plans

As Dr. Chambreau noted when she first began in veterinary medicine, conventional treatment for kennel cough varies, from simply keeping the dog quiet and avoiding drafts and strenuous exercise, to administering antibiotics (which are useless if the pathogen involved is a virus and not a bacterium). Some veterinarians may recommend a cough suppressant, but others, such as Dr. Fallek, contend that cough suppressants further weaken the immune system.

Dr. Fallek is trained in homeopathy, and she finds kennel cough relatively easy to treat with this energy-based modality. Though a dog’s individual symptoms should be used to select the correct remedy, one that Dr. Fallek finds works in many cases is Bryonia, which is indicated for coughs that are made worse by movement.

Dr. Chambreau, who is also a homeopath, notes that kennel cough often can be stopped in its tracks if the homeopathic remedy Aconite is administered at the very beginning. “If you find there is a remedy that works for you [the dog owner], then you might use that,” she says. “Often people and their animals need the same remedy.”

When kennel cough is a concern in Dr. Dodd’s facility (a canine blood bank, utilizing retired racing Greyhounds who are available for adoption!), Dr. Dodds brews a tea made of the herb mullein, which is used for calming the respiratory tract and treating lung ailments.

While mullein is not an endangered plant – the ultimate volunteer, it can get a roothold anywhere, including sidewalk cracks – some popular herbs are. Dr. Chambreau suggests substituting marshmallow root for slippery elm, which is being overharvested because of the popularity of its medicinal bark. As a bonus, marshmallow is the gentler of the two, while still providing soothing relief to inflamed mucous membranes. For throat soothing, Dr. Chambreau suggests aloe vera and raw honey.

Relationship between Canine Influenza & Circovirus

No matter what modality they use, Dr. Chambreau encourages owners to do their homework. No treatment is without its risks, and working with a trained practitioner is the best way to ensure that your healing intentions come to fruition.

If you spend any time on the Internet, you’ve come across frantic references to canine influenza and circovirus. There seems to be an inverse relationship between the hysteria that mention of these two viruses induces, and what people actually know about them. Let’s take the oldest one first.

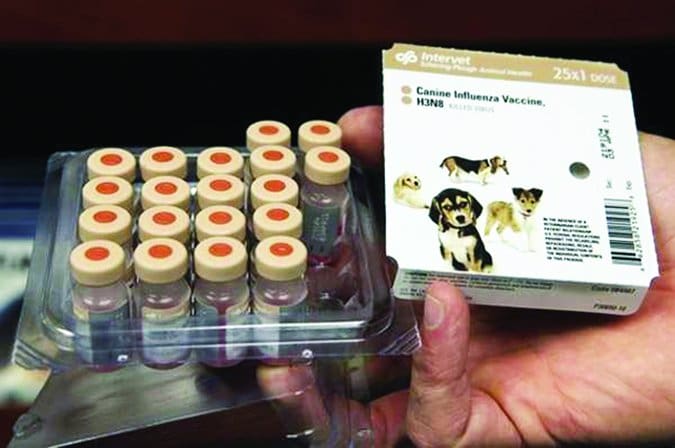

Canine influenza – specifically, canine influenza virus subtype H3N8 – first surfaced in a Greyhound kennel in Florida in 2004. A mutated version of a horse flu that “jumped species,” dog flu is highly contagious and produces symptoms that are similar to kennel cough – cough and runny nose. Dogs may also have a thick nasal discharge, which is usually caused by a secondary bacterial infection. But one thing that sets it apart, Dr. Dodds says, is the presence of a fever.

Like kennel cough, “canine influenza is generally not a disease of much clinical significance, despite the fact that it is a highly contagious virus,” says Dr. Dodds. For that reason, the canine influenza vaccine is not recommended for routine use, “except when animals may be exposed to high-risk situations such as crowded competitive show events, in which case it should be given prophylactically beforehand – two doses, three weeks apart.”

Dogs are at the greatest risk of complications if they become infected with the flu at a time when they are already coping with another stressor, such as intestinal parasites, malnourishment, or another infection.

“The only other dangerous scenario with this virus is when the dog has an upper or lower respiratory infection with streptococcus,” Dr. Dodds says. According to Ron Schultz of the Department of Pathobiological Sciences at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, in that scenario, two to three percent of dogs infected with canine influenza and strep can die from the co-infection.

The latest panic-inducing virus is canine circovirus. Last fall, media reports about dogs who contracted some sort of lethal virus in Ohio, and then later, in Michigan, were thought to have suffered from circovirus. However, investigators later concluded that while some of the affected dogs were infected with circovirus, it was not the primary cause of their illness. In an update published in November, Thomas Mullaney, interim director of the Diagnostic Center for Population and Animal Health at Michigan State University in Lansing, said, “Based on our current evidence, dog circovirus is not cause for panic.”

It is, however, cause for greater investigation. “I don’t think we really understand circovirus,” Dr. Dodds says. “It’s like giardia; it’s everywhere. What we don’t know is why it causes a major clinical problem in some dogs and not others.” There is also no vaccine for circovirus at this time.

Circovirus symptoms are more diffuse than those of kennel cough or canine influenza. They include vomiting, diarrhea (possibly bloody), and lethargy, though some dogs exhibit a respiratory component, such as coughing.

Researchers have been able to identify circovirus in lab samples from cases as far back as 2007. “The virus went undetected in dogs for several years and probably longer,” Mullaney wrote. “This supports the theory that dog circovirus exists as a subclinical infection, or as a co-infection with other well-recognized pathogens.”

Bottom line? Like kennel cough and canine influenza, circovirus isn’t a major problem for most dogs, but for some it will be. The best way to ensure that yours isn’t in the latter group is to keep her immune system robust and ready to meet the next challenge.

The Holistic Toolbox for Treating Kennel Cough

I’ve had dogs for most of my adult life, and I’ve dealt with kennel cough more times than I can count – though less and less as the years go by and I learn how to rear dogs with immune systems that can shrug it off. Like anything, how we choose to protect and treat our dogs is an evolution and a journey. Here’s where mine has taken me.

Early on in my life with dogs, I vaccinated for kennel cough. Until, that is, one of my fully vaccinated dogs picked it up at a show. Despite being put on antibiotics, he developed pneumonia, and though he recovered, his hospitalization left me with a whopper of a vet bill. I drew two conclusions from that experience: One, I needed pet insurance. And, two, maybe the vaccine wasn’t all it was cracked up to be.

From that point on, I didn’t vaccinate for kennel cough (along with a lot of other things, but that’s a different story). I found that my young dogs tended to develop the most severe symptoms when they first encountered kennel cough, usually at a dog show. By contrast, my oldsters, with their wise and still vibrant immune systems, didn’t even sniffle.

After some trial and error, I came across what has become my go-to modality any time I hear that telltale hacking: the homeopathic remedy Drosera. Any time I administer it, the coughing stops in its tracks, and asymptomatic dogs in the household stay that way.

That said, I’ve talked to holistically minded folks who have had zero success with Drosera. One homeopath told me it has never worked for her, even though it is considered a potential remedy for kennel cough. Perhaps there is just something about me and my home that dovetails with Drosera energetically. Whatever it is, it has never failed me -with one exception.

Several months ago, I had a litter of puppies that was off to a shaky start. The dam had a Caesarian section, and the litter was less than half the size of a typical one for my girls: only four puppies, one of which faded hours after she was born. Less than a week later, Cocoa started hacking: It was kennel cough, picked up in those few hours at the vet’s office.

Trusty Drosera to the rescue: I dosed Cocoa, and her coughing stopped within hours. I dosed her babies, too, and, because I had never had puppies this young exposed to kennel cough – and none of my mentors or fellow breeders had, either – I started them on antibiotics.

(I feel a little self-conscious and even defensive about admitting here that I used antibiotics prophylactically, ven though I believe the decision to have been a correct, potentially even life-saving one; the small litter size and fading puppy suggested to me the possibility of a low-grade infection. But it says something about how militant “holistic medicine” enthusiasts can be when a conventional modality is chosen as a first course of action; sometimes we fall into the same reflexive judging that we complain about with an allopathic approach! And that’s not “wholism.”)

Several days later, the large male (who was so big and vigorous that we had dubbed him “Chubsy”) began making odd noises, which got worse if he moved around. Despite all my precautions, he had contracted kennel cough, and the noise I was hearing – sort of a snore, really – was a “stertor,” caused by a partial obstruction of the airway above the larynx.

Thankfully, Chubsy was still active and eating, and a quick vet visit showed his lungs to be clear. I consulted my copy of Boericke’s materia medica (a homeopathic encyclopedia) for other remedies that might help him fight off the kennel cough. But he didn’t improve.

After several days, I decided to switch to another modality I was comfortable with, essential oils, which shouldn’t be used in conjunction with homeopathic remedies because they antidote them.

I have had success staving off colds with Thieves Essential Oil. A proprietary blend of therapeutic-grade oils from Young Living, it’s named for the four grave-robbers of medieval legend who avoided contracting the plague from the cadavers they pilfered by swathing themselves in oils (that turn out to have antimicrobial properties). The oil is a wonderful immune booster; when colds and viruses make their wintertime rounds, I do family foot rubs of Thieves diluted in almond oil to keep us sniffle-free.

Mindful that essential oils can be very powerful, I used a diffuser to disperse the oil in the puppies’ room, for short periods several times a day. I watched the puppies and their mother closely for any negative reactions.

To the contrary: Chubsy improved almost immediately, and within a few days, all signs of the infection – including that sleep-anea-like stertor – had disappeared.

Thanks to that experience, I have another addition to my toolbox if kennel cough crosses my dogs’ paths again.

Denise Flaim of Revodana Ridgebacks in Long Island, New York, shares her home with three Ridgebacks, 10-year-old triplets, and a very patient husband.

How to Survive Your Dog’s Arousal Biting

You’re frustrated with your dog. Maybe even a little frightened of him. Since puppyhood he’s been a happy and loving companion, star of his puppy training class, soaking up new experiences without turning a hair. You were even thinking of making him a therapy dog. But in recent weeks he has started offering new behaviors that have you puzzled and alarmed. When you try to take him for a walk on leash, he grabs the leash and shakes it, or – worse – grabs at your clothing. At home, he will occasionally launch at you with no warning, biting your pant legs or shirtsleeves. It’s getting worse – becoming more frequent, and he’s biting harder. He’s turning into a shark, and you have the puncture marks dotting your arms to prove it.

This alarming behavior can start early, even with puppies as young as six to eight weeks (See “How an Intense Behavior Modification Program Saved One Puppy’s Life,” WDJ April 2012), and even more commonly appears in adolescence – perhaps an interesting canine parallel to human teenagers running amok. It often erupts when there’s been a period of prolonged inactivity, such as inclement weather preventing outdoor exercise, or an owner working unusually long hours. There may be a number of additional influences on this sharky, biting behavior:

– Early experience in the litter. Singleton pups (those who have no littermates) seem particularly prone to hard mouthing, as do pups taken away from their litters too early (prior to the age of eight weeks). Since they have no siblings to let them know they are biting too hard, they may fail to learn good bite inhibition. (See “Teaching Bite Inhibition,” June 2010.)

– Inappropriate play with people. I counsel my clients to avoid roughhousing with their dogs in a way that encourages the dog to make mouth contact with human clothing or skin. Although not always, it is often male humans who take pleasure in games of growly rough-and-tumble. I do my best to direct those activities to appropriate games of tug, where the human can play rough and the dog learns to keep his mouth on appropriate play objects. (See “Tug O’ War,” September 2008.)

– Inadequate physical exercise. There’s nothing like excess energy to prompt a young dog to use his mouth in play. I have fostered several puppies and young dogs who hadn’t passed their shelter’s assessments due to excessive mouthing, and in every case, ample exercise was instrumental in modifying their behavior.

– Inadequate mental stimulation. Add “boredom” to excess energy and you have a surefire recipe for disaster. This is the dog who is seriously looking for something to do with all his excess energy, and discovers that he can engage you in his games by using his teeth. Not a good solution!

The good news is that canine sharks are not a lost cause. There are remedies at hand, and most are quite simple to implement if you are willing to invest a little time and effort.

Life in the Litter

If you plan to adopt a pup from a shelter or rescue, you may (or may not) have the privilege of seeing the litter interacting together. If so, at least you know there’s a litter, so the singleton pup concern is not an issue. If you are purchasing from a breeder, be sure to ask how many pups were in the litter and how long they stayed together. Might as well sidestep a problem if you can!

If you get to watch littermates playing together, watch how it works. Usually, if one pup bites another too hard, that pup yelps or snarls and moves away for a moment. The pup who bit will normally readjust his play, re-engage his sibling, and play will continue. A pup who continues to bedevil his littermates and continues to bite hard even when they let him know they don’t like it is likely a shark in the making. Pick a different pup, or be prepared to deal with the behavior.

The best behavioral solution for a singleton pup is for the breeder, shelter, or rescue group to find two or three “spare” pups from another litter and import them with careful introductions to mom, so the pup has brothers and sisters. This is preferable to removing the singleton and placing it in a different litter, since mom will likely grieve the loss of her baby. The exception would be if she isn’t adapting well to motherhood and is not taking good care of the pup, or has some medical issue that prevents her from mothering.

If you somehow acquired a pup prior to the age of eight weeks, ask your dog friends and animal care professionals (vet, groomer, trainer) if they know of any litters of a similar age that your pup could spend time with (daily!).

Tug O’ War

I already mentioned the wisdom of playing a hearty game of tug-o-war rather than physical contact sports. Some old-fashioned trainers still warn against tug with gloom-and-doom predictions about dogs who are allowed to show their “dominance” and resulting “aggression” in the game. I had a client just the other day whose prior trainer said exactly that. He and his dog were as happy as a kid at Legoland when I gave them permission to play tug. The rules are short and simple:

Dog is not allowed to rudely grab tug toy from your hand; have him wait politely for permission (the cue) to grab. I use “Tug” as my cue. If my dog grabs for the toy before I give the cue, I give a cheerful “Oops!” and whisk the toy behind my back.

Make sure the dog will “trade” (give you the toy in exchange for something else) – either on cue, or for a treat.

Take several “trade” breaks from tugging during the game, in order to solidify polite good manners.

Canine teeth touching human skin or clothing is cause for a cheerful “Oops, time-out!” This uses gentle “negative punishment” (wherein the dog’s behavior makes a good thing go away) to teach your dog that the funs stops if his teeth touch human skin, and gives your dog a brief arousal break – time to calm down before play starts again.

Give That Dog Exercise

The last thing you may want to do when you come home exhausted from a day of work is exercise the dog. Your dog, however, has been lying around the house all day just waiting for you to come home to play with him, and you – or someone in your family, or a dog walker – has to oblige. That was the contract when you got him, remember? His excitement over your return and in anticipation of his walk put him at a keen edge of arousal, and tug-the-leash is a natural game choice for him. But you mustn’t allow yourself to get drawn into a game that usually ends with your dog overstimulated and you upset (or frightened or hurt)!

It behooves you to get rid of some of your dog’s energy before you take that on-leash walk. Of course he has to relieve himself after being indoors for hours. If you have a backyard, allow him to relieve himself there, and then play with him there before you try to take him for a walk. Play hard. Throw his ball. Throw a stick. Have him go over jumps as part of his fetch game. If he’s so aroused already that he’s grabbing at you while you play, put yourself inside an exercise pen you leave set up outdoors for that purpose (or behind your closed porch gate) and throw toys or play with a flirt pole from inside the pen until he’s tired.

Alternatively, if your dog’s not the fetch-’til-you-drop kind, go out in the yard and scatter small but tasty treats all over. He will exercise himself as he criss-crosses the yard in search of treasure, working his nose. (Nose exercise is surprisingly tiring for a dog.)

If you don’t have a yard, you probably have to take your dog out on a leash at first to let him eliminate using one of the management solutions described below. When he’s empty, bring him back indoors and play physical inside games such as tug, chasing toys or treats down the hall, until you’ve taken the edge off. Then put the leash back on and go for that walk! (Note: If you just rush him back inside when he’s empty and don’t play, or don’t go for the after-walk, your dog may learn to “hold it” as long as possible to enjoy the outing.)

Brain Exercises for Dogs

Mental exercise can be every bit as tiring as physical exercise. (I remember in the early 1990s coming home from work exhausted after trying all day to figure out how these new-fangled “desktop computer” things were supposed to work.) On those days when you can’t play in the yard with your dog (or if you don’t have a yard to play in), take advantage of the multitudes of interactive toys now on the market. Or make your own: treats in a muffin tin with tennis balls covering the holes can work nicely to occupy your dog and exercise his brain. In addition, sign the two of you up for a force-free basic good manners class. If you’ve already done basic, go for the more advanced classes. Brain candy. Once you have taken the edge off with physical or mental exercise, give your dog 10 to 15 minutes to calm down, and then put his leash on for that neighborhood walk. If he’s new to the leash-tug game, that may be all you need to do. If it’s a well-established behavior, however, you may need some additional management measures in order to help extinguish the game.

Manage Your Dog’s Behavior

Management is always an important piece of a successful behavior-change program. The more often your dog gets to practice (and be reinforced for) his inappropriate/unwanted behaviors, the harder it is to make them go away. Here are some ideas to get you by until your shark has turned into a pussycat.

– Choke Chain. Yep, you read that right. I love to watch the shock and dismay on the faces of my academy students when I tell them that this is the one time I will actually still use a choke chain. Then I pull out a double-ended snap or a carabiner, and snap one end of the chain to the dog’s collar ring, and the other to the leash. Voila! You now have 12 to 24 inches of metal chain between your dog’s collar and your leash. When he goes to bite the nice soft leash for a fun game of tug he bites on metal instead. Most dogs don’t like that – so they quickly learn that tug isn’t any fun anymore and stop trying to bite the leash.

– PVC Pipe. Slip a 5-foot piece of narrow-gauge, lightweight PVC pipe over your 6-foot leash. Again, your dog’s teeth have nothing soft to bite on, and they will slide right off the pipe. Additionally, although it is somewhat awkward, you can use the stiff pipe-leash to hold him away from you if he is trying to grab you or your clothing.

– Two Leashes. Snap two leashes on your dog’s collar. When he goes to grab one, drop it and hold onto the other. If he goes for that one, grab the first one again and drop the second. The fun of tug is the resistance you apply on the other end (because you can’t just drop the leash and let him run off). If there’s no resistance, there’s no fun (no reinforcement) and the game goes away.

– Tether. This one isn’t for all dogs, but works for some. Put a carabiner on the handle end of your (heavy duty) leash. When your dog starts grabbing at you, tether him to the nearest safe and solid object and walk a few steps out of reach. (Don’t use this one for dogs who will bite right through their leash, or who panic if you leave them.) Make sure you do not tether him where he can run into traffic or assault pedestrians. Return to him when he is calm. If he amps up on your return, step away again. Repeat as needed.

– Head Halter. These are not my favorite piece of training equipment (most dogs find them aversive), but this is one of the few times when the head halter may still have a place in positive reinforcement training, because it does give you control over the dog’s head in a way that a front-clip control harness does not. With a head halter, you can actually use the leash to prevent your dog from grabbing you with his jaws by putting pressure on the outside of the halter, away from you. If you are going to use one, however, you must take the time to convince your dog that a head halter is wonderful before you actually start using it. (See “Teach Your Dog to Love a Head Halter,” next page.)

– Baby Gates. While much of this unwanted behavior tends to happen out of doors, especially when on a leash, some dogs expand their aroused biting to indoor interactions as well. Pressure-mounted baby gates (so you don’t have to put holes in your door frames) are a quick and simple way to put a barrier between you and your shark when teeth are flashing. You can even exercise your dog indoors using gates, similar to the method described above with the exercise pens. Just stand on the opposite side of the gate from your dog and toss your heart out.

– Redirection. You often have some warning before the biting behavior occurs. You see the gleam in your dog’s eye, or he does a couple of puppy rushes around the dining-room table. Perhaps it always happens in a particular room, or at a certain time of day. Be prepared! Have a plastic container of treats on an out-of-reach shelf in every room, and when you sense a shark attack coming on, arm yourself and start tossing to divert his attention, redirect his teeth and give him some exercise, all at the same time. Remove yourself to the other side of a baby gate, if necessary.

– Muzzle. If your dog still manages to grab onto you despite all your efforts, you may want to consider conditioning him to a basket muzzle when he is with you. (This sort of muzzle is not the same as the kind often used for restraint in vet offices; basket muzzles allow a dog to breath, drink, and even eat, but prevent him from biting. Do not leave one on him unattended, however.)

This requires the same conditioning process as the head halter, so it isn’t a quick fix – and there is some social stigma attached to your dog wearing a muzzle. You might elect to use it when there are particularly vulnerable humans present (small children and seniors). If you choose to use one, follow the same steps outlined below, to convince your dog that his muzzle is wonderful.

It would also be a good idea to explore other energy-sapping activity options for your dog. Investigate doggie daycare, if there is a decent one in your community and your dog is daycare-appropriate. (See “Doggie Daycare Can Be a Wonderful Experience” November 2010.) A well-run dog daycare will give him great opportunities for exercise and social interaction.

A professional pet walker is another option, assuming you can find one skilled enough to handle your dog’s mouthiness and willing to follow your explicit instructions about how to work with the behavior. If there’s no good daycare in your area, find some appropriate canine pals for your dog and arrange playdates. If you can find another dog who has a similar style of playing, they can gnaw on each other to their hearts’ content and come home tired, so your dog can behave more appropriately with you.

Of course, if after all that you think there is an element of real aggression in your dog’s biting, or if the behavior is too overwhelming, by all means seek out the services of a competent, force-free behavior professional to help you through the shark-infested waters. Properly handled, your dog can outgrow this phase, and the two of you will be on to smooth sailing.

Why You Never Hurt or Scare a Dog

It should go without saying that we would never advocate verbally or physically punishing your dog, but just in case, here are five reasons why physically hurting or scaring your dog is a bad idea:

1. You can cause physical harm to your dog.

2. You aren’t teaching your dog what to do instead of biting. You leave a “behavior vacuum,” which he is likely to fill with the behavior he knows – being sharky.

3. You can inhibit your dog’s willingness to offer desirable behaviors due to his fear/anticipation of being punished.

4. You can damage your relationship with your dog, cause him to fear you, and teach him to run away from you.

5. You can turn your dog’s easily managed and modified aroused/excitement biting into serious defensive aggression.

Introducing a Head Halter

Your best chance for convincing your dog his head halter is a wonderful thing is to pair it with high-value treats from the very beginning (this is classical conditioning). At first, and between steps, put the head halter behind your back. This process should take at least several sessions. If your dog is happily going along with the program, it’s fine to continue – but try to always stop before he becomes unhappy with the process. If your dog becomes anxious at any point, or resists the process, back up to an easier level and then figure out how to add more steps in between. If your dog starts fussing, distract him to stop the fussing, and then take the halter off after a bit and slow your training program. Here are the steps (repeat each step many times):

1. Show the dog the head halter and feed him a tasty treat. Repeat until his eyes light up when you bring out the halter.

2. Let him sniff/touch the halter with his nose and feed him a tasty treat. Repeat until he is deliberately and solidly bumping his nose into the halter.

3. Let him sniff through the nose loop of the head halter. Feed him the treat through the nose loop. Repeat until he eagerly pushes his nose into the loop.

4. Attach the collar around your dog’s neck (without the nose loop) and feed him a treat. Remove after one second. Repeat many times.

5. Attach the collar band around your dog’s neck (without putting the nose loop on) and feed him a treat. Gradually increase the length of time that the collar is on your dog.

6. Let your dog push his nose into the nose loop. Keep the loop on his nose for one second. Feed him a treat. From now on, feed all treats through the nose loop.

7. Let your dog push his nose into the loop, gradually keeping it there longer and longer, until he is holding his nose in the loop for 10 seconds. Treat several treats. This should take many repetitions.

8. Let your dog push his nose into the nose loop, and then bring the collar straps behind the head for a second or two. Do not fasten them. Feed him a treat and remove the nose loop.

9. Repeat the previous step, gradually keeping the head halter on longer and longer, until you can hold it there for five seconds. Treat several times.

10. Put the head halter on and clip the collar behind his head (without a leash attached to it). Treat and remove the collar. Repeat many times, gradually leaving it on longer and longer. Treat generously.

11. Put the halter on (without a leash attached to it) and invite your dog to walk around the room. Feed treats.

12. Attach the leash and take your dog for a short walk – in the room at first, then gradually longer, and outside. Be generous with treats. Now you can use the leash and head halter to gently move his head away from you if he starts to get grabby.

Here is an excellent YouTube video of the wonderful force-free trainer, Jean Donaldson, conditioning her Chow, Buffy, to love a head halter.

Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, is WDJ’s Training Editor. She lives in Fairplay, Maryland, site of her Peaceable Paws training center.

(Holistic Remedies #3) – Causes for Hot Spots

Your dog has a weeping, oozing wound on her leg or a yucky red blob on the top of her head, and at first you wonder how she injured herself. But if you’ve been around the dog-care block, you realize that it isn’t a cut or a scrape. That gooey mess might be diagnosed as pyotraumatic dermatitis, wet eczema, or a Staphylococcus intermedius infection, but it’s what everyone calls a hot spot.

Most veterinarians treat hot spots after clipping and shaving fur around the lesion, a process that in severe cases can require sedation or the use of a local anesthetic. The area is washed with a disinfecting soap or rinsed with a liquid antiseptic. Astringents, anti-itch agents, antihistamines, hydrocortisone sprays or creams, drying agents, or antibiotics may be applied. In some cases topical treatment is accompanied by steroid infections or oral medication.

Because conventional therapies can have serious side effects and because hot spots are notorious for recurring, holistic veterinarians look beyond their obvious symptoms to their underlying causes.

According to Richard Pitcairn, DVM, PhD, author of Dr. Pitcairn’s Complete Guide to Natural Health for Dogs and Cats, skin disorders stem from:

- Toxicity, most of it from poor-quality food and some from environmental pollutants or topically applied pest-controlled chemicals.

- Vaccinations, such as routinely administered multiple vaccines, which can induce immune disorders in susceptible animals.

- Suppressed disease, the remains of inadequately treated conditions that were never cured and which may cause periodic discharge through the skin.

- Psychological factors such as boredom, frustration, anger, and irritability.

So rather than focusing 100% on the symptoms, Dr. Pitcairn says “It is possible to alleviate or even eliminate skin problems simply through fasting, proper nutrition and a total health plan.”

For more information on holistic approaches to common canine conditions and illnesses, purchase and download the ebook Holistic Remedies from Whole Dog Journal.

5 Common Mistakes to Avoid When Buying & Feeding Dry Dog Food

The vast majority of dog owners feed dry dog food to their dogs – and quite a few of them select and store the bags of food in a way that turns a wholesome food into a health hazard for their beloved companions. Are you handling your dog’s food in a safe manner? Or do you regularly make the following mistakes?

1. Grabbing and buying the first/top bag on the shelf.

Always check the date/code on the bag, and buy the bag with a “best by” date that is as far in the future as you can find. And don’t buy bags that are within a few months or closer to their “best by” date.

Most foods that are made with natural preservatives are intended to be consumed within 12 months of manufacture, although companies extend this to as much as 18 months. But dry food is far less nutritious (oxidation slowly decreases the vitamin activity), and has far more potential to be rancid, the more time passes post-manufacture. (Note that foods that are packed in vacuum-sealed bags and flushed with nitrogen keep fresh longer.)

So, for example, if its February 2014, a bags that was just manufactured and placed on the shelf should have a “best by” date of February 2015 – buying that bag would be ideal. In contrast, avoid the bag with a “best buy” date that indicates the food should be consumed within the next few months.

2. Buying giant bags for your small or medium dog.

It’s fine to buy the biggest bag if you have several large dogs, but the point is, you should be buying bags in sizes that are small enough so that the food is entirely consumed within two to three weeks, no more.

The longer the food is exposed to oxygen once the bag is open, the faster it oxidizes. While buying very large bags makes the most economic sense (the price per pound is always less if you buy in large bags), it may not make the most sense for your dog’s health. Many dogs start turning up their noses at a food by the time you reach the bottom of the bag, because by that time (especially if you have a small dog!), the fats in the food may be quite rancid – and dogs’ noses are far more sensitive to the odor of rancid fats than our noses are. Veterinarians have a phrase for what happens when dogs are not fussy and eat rancid food, suffering digestive upset after meals: “bottom of the bag syndrome.”

3. Storing the food in a warm or damp place.

Read the label; it will almost always suggest storing the food in a cool, dry place. Again, this is to preserve the wholesomeness of the food and to retard the process of oxidation. Look for a cool, low cupboard or shelf in the pantry.

4. Dumping the food into another container.

I know, I know, it’s far easier to scoop food out of a plastic bin than it is to scoop it out of the bag. But there are several problems with bins. First, many are not made with “food-safe” plastic – material that is resistant to degradation caused by contact with fat (keep in mind that dog food is a relatively high-fat food). Fat can cause the type of plastic used in things like plastic garbage cans and totes to accelerate the rate at which BPA and other plasticizers leach out of the container and into the dog food.

Second, if you don’t completely empty and clean out the bin in between each bag of food you dump into it, you are effectively “seeding” each new batch of food with rancid fats that are in the old food in the bottom of the tub and the fat that covers the container. It’s far safer to keep the food in the bag, and keep the bag in a container.

The practice of dumping the food into another container leads to the next mistake you should avoid . . .

5. Throwing away the bag before your dog has finished all the food.

If your dog becomes ill, the type of food and its date/code number will be critical information to have on hand. Your vet will want to know what exact food you fed the dog. If it develops that the food causes a serious illness or death, the manufacturer and the FDA will need the information to conclusively tie the food (and the specific lot of food) to the problem. If you are not absolutely certain and/or can’t prove what variety of food you fed to your sick dog, it’s will be very difficult to make the company take responsibility for the problem.

Professional Dog Training Titles

Not to be outdone by the veterinary profession (See “How to Decipher Veterinary Code,” WDJ October 2013) or even dogs themselves (“Dog Certifications and Titles,” January 2014), the dog training and behavior profession also boasts a mind-boggling array of letters that may appear at the end of a trainer’s name. In some cases, the initials identify a person with considerable education and experience with canine behavior, but others indicate little more than membership in a dog-training organization, so it pays to know what those letters mean!

You may be surprised to discover that there are no educational, experience, training, skill, certification, or licensing requirements for anyone to call themselves a dog trainer or behaviorist in the United States. None. Zip. Zero. Nada. Your plumber could decide to hang out a shingle and start training dogs tomorrow, even if he or she has never touched or even seen a dog in his or her entire life.

Fortunately, there are scores of excellent educational opportunities for animal training and behavior professionals to increase their skills and knowledge, and many do, in fact, attend courses and seek various kinds of certification in the field. In fact, the number of qualified, well-educated training and behavior professionals has increased dramatically since the 1990s.

True Animal Behaviorists

While the media tends to refer to anyone who will comment on any animal’s behavior as an “animal behaviorist,” there is growing agreement among ethical behavior and training professionals that the term “behaviorist” should be reserved for those in the field who have advanced degrees in behavior and/or veterinary medicine and behavior. Those who don’t have such degrees and who wish to show respect to degreed behaviorists use terms like “behavior consultant,” “behavior counselor,” and “behavior professional” to describe what they do. That said, plenty of people who offer services in training and behavior disregard that courtesy.

DACVB: At the top of the behaviorist food chain is the “veterinary behaviorist” – a veterinarian who meets the rigorous qualifications set by the American College of Veterinary Behavior (ACVB) and passes the two-day veterinary board exam in behavior. These board-certified specialists are known as diplomates; a diplomate of the ACVB = DACVB. One who calls himself a veterinary behaviorist without this credential is practicing veterinary behavioral medicine without a license and is subject to prosecution.

In addition to passing the board exam, the requirements include the equivalent of an internship; a conforming residency at an approved university program, or a non-conforming training program which was mentored and approved by ACVB; a supervised behavioral caseload (the first 25 clinical cases are seen with the mentor present, 25 of the next 50 cases are seen under the supervision of the mentor, close supervision is required for the first 200 cases); authoring a scientific paper published in a peer-reviewed journal based on the candidate’s own research; and writing three peer-reviewed case reports.

Given the requirements, it’s understandable that there are fewer than 100 DACVBs in the world, most in the United States and a handful in Canada.

CAAB: Next in line is the Certified Applied Animal Behaviorist (CAAB). In order to become a CAAB, one must meet the qualifications set by the Animal Behavior Society (ABS).

There are two different possible paths to acquisition of this title. The first requires a Phd (doctoral degree) in a biological or behavioral science with an emphasis on animal behavior, and five years of professional experience.

The second path requires a doctorate in veterinary medicine plus two years in a university-approved residency in animal behavior and three additional years of professional experience in applied animal behavior.

Other requirements of this second path include: demonstrating a thorough knowledge of the literature, scientific principles, and principles of animal behavior; submitting original contributions or original interpretations of animal behavior information; showing evidence of significant experience working interactively with a particular species as a researcher, research assistant, or intern with a Certified Applied Animal Behaviorist prior to working independently with the species in a clinical animal behavior setting; attending and presenting a contributed talk or poster at an ABS Annual meeting prior to applying for certification; and meeting all the requirements for an Associate Certified Applied Animal Behaviorist (see next).

ACAAB: The Associate Certified Applied Animal Behaviorist is the next rung down the ladder. Don’t let the “Associate” fool you; the requirements for this level of certification are still stringent: First, the applicant must obtain a Master’s degree from an accredited college or university in a biological or behavioral science with an emphasis in animal behavior. The degree should include a research-based thesis. Coursework must include 30 semester credits in behavioral science courses, including 9 semester credits in ethology, animal behavior, and/or comparative psychology; and 9 semester credits in animal learning, conditioning, and/or animal psychology.

Next, the candidate must provide evidence of a minimum of two years of professional experience in applied animal behavior; show evidence of significant experience working interactively with a particular species (such as a researcher, research assistant, or intern working with a certified applied animal behaviorist) prior to working independently with the species in a clinical animal behavior setting; attend and present a contributed talk or poster at an ABS annual meeting prior to applying for certification; and must also provide a minimum of three letters of recommendation, one from a Certified ABS member and one from a regular ABS member affirming the applicant’s professional experience in the areas listed above. There are about 50 CAABs and ACAABs combined.

With fewer than 100 certified behaviorists in the entire United States (many of whom do not work with companion animals), the dog population would be seriously underserved if there were not other qualified behavior and training professionals to be found. Fortunately, a number of organizations created to further the education of dog trainers have emerged in the past few decades.

APDT: Recognizing the need for professionalism in the dog training field, in 1991 British veterinary behaviorist Ian Dunbar founded the Association of Pet Dog Trainers, intended as a forum for trainers to network with each other and provide educational opportunities. APDT, which was recently renamed the Association of Professional Dog Trainers, held its first annual educational conference in Orlando, Florida, in 1993.

The annual conference continues to this day, joined by frequent webinar offerings. While the APDT itself does not certify trainers nor are its members necessarily committed to force-free training, this organization did launch the CCPDT in 2001 (see below), which has certified more than 2,000 training and behavior professionals worldwide. With more than 5,000 members, APDT is the largest dog training membership organization in the world.

AVSAB: The American Veterinary Society of Animal Behavior (AVSAB) is a group of veterinarians and research professionals who share an interest in understanding behavior in animals. Founded in 1976, AVSAB is committed to improving the quality of life of all animals and strengthening the bond between animals and their owners. Membership in this organization is open to all veterinarians, veterinary students, and non-veterinarians who have a Phd in animal behavior or a closely related field.

Membership in AVSAB is not a certification, and so is not a statement of member skills or qualifications in behavior work.