Over the course of 20 years, the physical-rehabilitation department of various healthcare facilities became my second home as I groaned, stretched, and struggled my way through physical-therapy sessions following the gradual deterioration and the amputation of my lower legs (due to vascular disease). I was highly motivated to get my body working efficiently again, and I knew the sessions were necessary for physical improvement, but I found the endless repetitive exercises boring to do. Why couldn’t physical therapy be more fun and interesting?

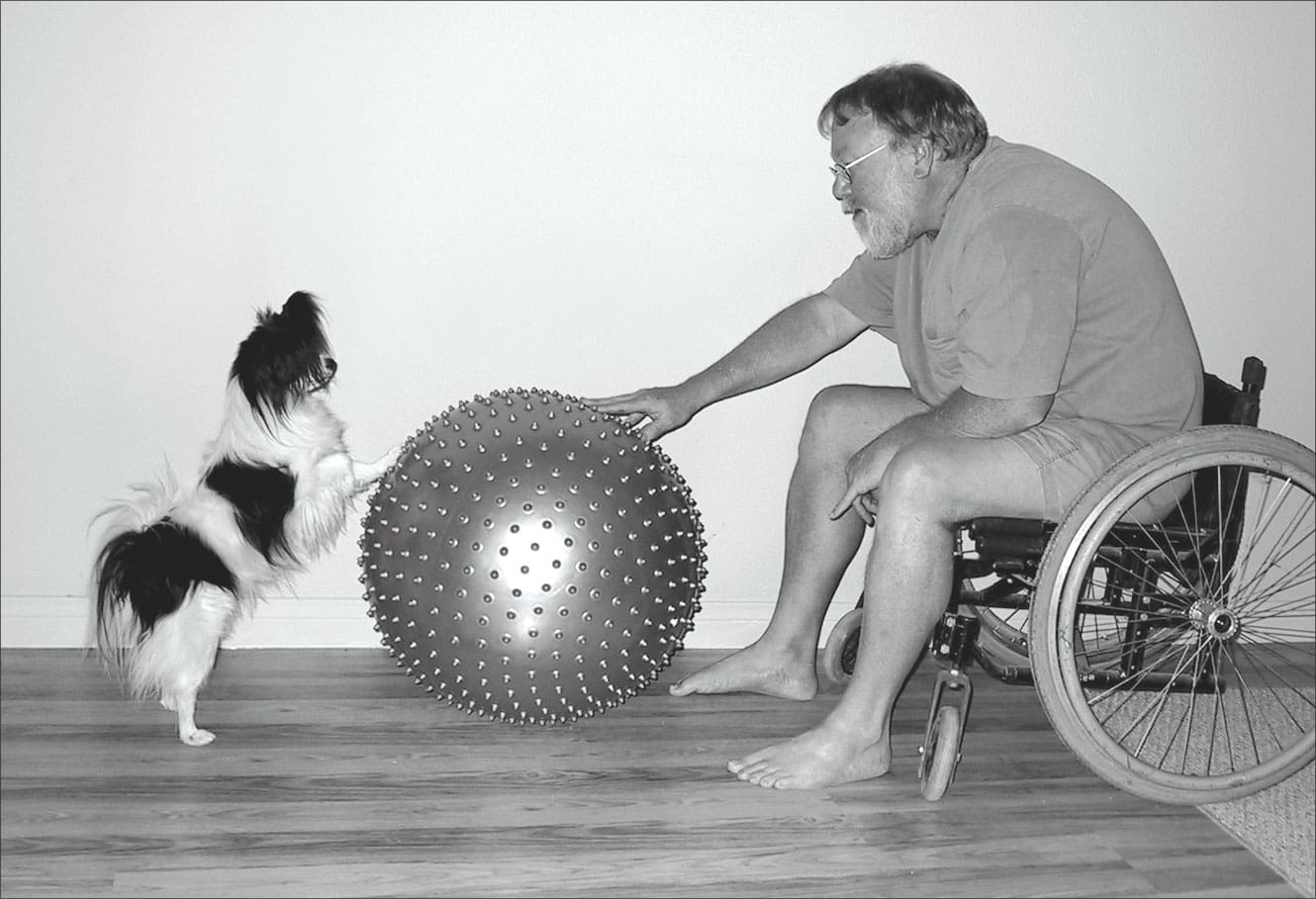

A decade later I was asked to participate in the creation of a new animal assisted therapy (AAT) program at a local hospital’s physical-rehabilitation department. My service dog Peek, a 10-pound Papillon, enjoyed interacting with people without soliciting their attention, and he had become bombproof in public. It seemed like a perfect fit for both of us; he enjoyed active participation and tasks, and I enjoyed bringing laughter into the physical-therapy department.

Peek and I had been through therapy-dog training and testing with Pet Partners® and were registered and insured to do both Animal Assisted Activities (AAA) and Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT). In AAT, the dog is an actual part of the patient’s individual treatment plan as a clinical tool, and the dog’s work is documented and kept as part of the patient’s medical records.

Peek enjoyed visitation, but he really came to life when allowed to do more physically interactive exercises and use his growing skill set. Common service dog tasks – such as retrieving, holding items, carrying items from one person to another, pushing and pulling objects – all became skills the physical therapists (PTs) could use to help make therapy sessions more enjoyable, and break the monotony of repetitive exercises. PTs found that patients doing their exercises while interacting with dogs were much more motivated to attend, and actually looked forward to their therapy sessions. Patients worked more diligently and tried harder when working with a dog.

Dogs working in physical-therapy sessions can help patients increase their strength, balance, mobility, flexibility, memory sequencing, reflex response, range of motion, endurance, and gross motor skills. As one therapist said, “Dogs help the grumpiest patients play longer and more complex therapeutic games.”

Because Peek and I enjoyed canine freestyle (dancing with dogs), this activity gave me another skill to help reward extra efforts of the patients who liked dogs. I’d taught Peek to respond to either voice or hand signals. I would show the client how to give the signal for Peek to stand up on his hind legs and turn around in a circle: “Pretend your finger is a spoon and you are stirring your coffee.” Then I’d show them the hand signal for a quick drop into a down position. The patients loved to end up their therapy sessions with a bit of dog dancing and fast drops.

Memorable AAT Dog Clients

Peek and I assisted in the rehabilitation of dozens of patients with a range of physical challenges and treatment goals, including:

Jenna was recovering from a stroke, and needed to do lots of gross and fine motor skill exercises. Instead of just squeezing a soft foam ball while the therapist watched and counted the repetitions, Peek would hold the ball while Jenna got a good grip on it, then he would stand patiently while Jenna squeezed the ball 10 times; then Jenna would throw it for Peek to retrieve. Exercising with resistance was done by having Jenna and Peek play tug and release. The dog would hold steady pressure on the rope as many seconds as planned by the therapist, and I’d cue him to release when the exercise was finished. Those ball-squeezing, resistance, and ball-tossing exercises were a whole lot more interesting with a dog.

Jenna also had to do exercises to restore hand facilitation and strength. Learning to manipulate buttons, snaps, clasps, and zippers again was much more fun when she could put clothing on Peek, and fasten and unfasten the closures. She also enjoyed learning to grasp and move a brush, by brushing Peek and learning to stroke the brush on his hair in a rhythmic fashion. At the end of her first therapy session with Peek, she said, “I never looked forward to therapy before. Now I can’t wait to get here!”

Joe had suffered a head injury in a farm-equipment accident and had to learn to use his legs and arms again. A ranch hand, Joe used to be a horseshoe-tossing ace, and his favorite therapy exercise was tossing rubber rings onto a board affixed with wooden dowels to catch the rings. Instead of the therapist gathering the rings and taking them back to Joe to be tossed again, Peek became the ring gatherer, and brought each rubber ring back and placed it on Joe’s lap after it had been thrown. Joe stepped up his pace and worked hard to get those rings on the pegboard, because he loved watching Peek jump up to retrieve them.

Joe also needed to do balance and stretching exercises. The PT would give me positioning points, and Peek would stand quietly in that position, so that Joe could stretch toward and try to reach Peek’s back. Peek would be directed to move around Joe’s wheelchair at various positions and angles so that Joe could reach and stretch to each side and the front of his chair.

Mr. Jenkins was learning to walk again, and had graduated from wheelchair to walker. He would push the walker and take a couple of steps while holding onto the dog’s leash. Peek would adjust his pace to Mr. Jenkins’. Each time Mr. Jenkins would stop for a little rest, he’d reach over and pat the dog, and say, “Just give me a moment, boy, and we can go another lap down the hallway.” What was once just a boring exercise had become fun and interactive with the dog at his side.

Is This An Activity For You and Your Dog?

Which skills are needed to work in a physical-therapy department with your well-mannered, well-socialized dog? The dog should be able to work off-leash, and do basic loose leash walking on both sides of your body, as well as next to a wheelchair, walker, cane, or crutches.

A trip to a local senior center or hospital can offer many opportunities to help your dog gain confidence around medical equipment. You can work your dog outside, practicing sits, downs, and standing in position until cued to do another behavior. Automatic doors that whoosh open and close, people pushing IV poles on casters go by, wheelchairs, walkers, and crutches are also abundant. Vehicles may pull in at the door to unload passengers from lift-equipped vans. People will exhibit lurching gaits, and the scent of disinfectant, alcohol, and other chemicals used inside hospitals and rehab centers will waft through the doors and linger on patients’ clothing.

Working outside a hospital emergency room can condition your dog to sirens, people rushing, and carrying in people on gurneys. I like to bring along a tin pan of some type, a book, and an umbrella. Dropping the book and the pan, letting the dog get used to the thump and clatter that is a normal part of any hospital rehabilitation unit, is very helpful. Open and shut an umbrella in every possible place, so the dog gets used to quick changes in the appearance of objects. You may also use this to help teach directions – right, left, and around – in a stimulus-rich environment.

With so many people enjoying dog sports and other activities with their companion and competition dogs, it might be worth evaluating how any of your dog’s current repertoire of behaviors might be turned into a skill that could help motivate and engage people in a physical-therapy setting. Of course, a dog with a good retrieve will always be in high demand, as there are so many ways to integrate retrieval games into physical-therapy exercise plans.

You can always start with core canine good citizen behaviors and refine and shape new behaviors as needed. A dog working in any AAA or AAT setting should be comfortable with people of all ages, sizes, cultures, and races, and not be stressed by busy, noisy environments.

A calm, relaxed, friendly dog who can walk on a loose leash and be comfortable being handled, groomed, and interacting with strangers will have what it takes to start a career as an animal-assisted physical-therapy dog. The dogs who already have obedience or rally skills will be in high demand. Off-leash work is also highly coveted. It’s a chance to show off your dog’s skills while doing something to help others. It can be as nourishing and fun for the dog and handler as it is for the patients who are fortunate enough to get to work with them.

Attributes of an AAT Dog

A great animal assisted therapy (AAT) dog can be of any breed or mix of breeds, and either sex. What’s important is that the dog is able to respectfully interact with all people without exhibiting stress. I’ve worked along side 3-pound Yorkies and 180-pound Mastiffs. Some patients will prefer to work with smaller dogs and some with larger ones. There will always be people who are not comfortable interacting with certain breeds, no matter how friendly and well mannered the dog may be. I recall a Holocaust survivor who loved dogs, and wanted to be part of the AAT physical therapy program, but was uncomfortable working with any dog resembling a German Shepherd, because it reminded her of the dogs used in the concentration camps. Some people view bully breeds as threatening, and others have been bitten by small dogs and cannot relax in their presence. It’s important that the handler not take it personally if a patient is uncomfortable working with a specific type of dog.

The personality of the AAT dog requires a dog who is comfortable being handled and interacting with people of all races, cultures, sexes, and ages. The dog should be friendly, sociable, and reliable in distracting environments. In addition, the AAT dog must be able to interact comfortably with other dogs (and sometimes cats!) working in the same room. The therapy room can get quite congested at times, so the dog should be able to remain calm and focused in crowded areas.

While AAT dogs should be friendly and sociable, the dog should also have acceptable public behaviors, and not sniff, jump, lick, paw at people, or coerce attention. The dog must also be confident enough to be handled awkwardly, and be comfortable being touched on all parts of the body.

The handler’s communication with the dog is equally important. Because physical-therapy dogs often work off-leash, the handler directs the interaction with the patient, and will cue the dog from different positions. The dog-handler relationship is one of trust, and the dog will be expected to interact with a stranger as directed by the handler, under the physical therapist’s guidance. Just as the dog is expected to remain focused on the tasks at hand, the handler must remain focused on the dog, and ready to give a cue to change from one behavior to another.

The more behaviors the dog has on cue, the more creative the therapist can be in including the dog in the patient’s treatment plan. Being able to respond to direction changes, position changes, sits, downs, and doing retrievals is extremely helpful. However, it’s not mandatory.

If your dog has good manners, is comfortable being handled and interacting with new people, isn’t stressed around medical equipment or crowds, and responds to basic obedience cues, then the dog may well enjoy doing AAT work.

It’s a team effort, however. The handler is as important as the dog, and should know how to read her dog’s stress signals and know when the dog may need a short break to just relax, sniff outside and eliminate. Though therapy sessions are normally only a couple of hours at most, it’s intensive concentration for both the dog and handler. Knowing your dog’s needs sets up both the handler and dog for success.