When I first started to learn about training, it was in the world of competitive dog obedience. In that specialized niche, dog training was mostly separate from everyday life. You trained the dog to do difficult but stylized stuff. It was a sport, a competition, a mini-culture. I jumped in, competing with several dogs. This changed the course of my life a bit, adding new interests, activities, and friends.

But a friend used to tease me and ask why this training didn’t include anything practical. Why didn’t it teach my dogs not to jump on her when greeting? I would weakly tell her about the Canine Good Citizen classes and test, which are a great step in the right direction in the obedience world. But I also knew in my heart that a dog could easily pass the CGC at that time and have poor manners in real life. (I know because I did it with two dogs!) There was something missing.

I only gradually learned about another type of dog training – one that is based on the science of learning but is also all about practicality. This type applies to everything from helping dogs get along in human homes to agility to search and rescue. (It applies beautifully to competitive obedience as well.) It considers the ethics of changing functional behaviors. It encourages us to learn about dog body language so that we may better perceive our dogs’ response to training and other situations. This type of training emphasizes enriching our dogs’ lives even as we may need to change some human-unfriendly behaviors.

It helps us realize that the laws of learning apply to humans too. Professional dog trainers train humans as much as they train dogs.

This was the new-to-me world of training that I had hoped was out there. This was the missing piece. And when I finally found it, the lessons I learned caused sea changes in my life, my beliefs, and my behavior.

Here are three of the many things I’ve learned:

1. Perceive the dog (or person) in front of me. I tend to live in my head. My friends tell me they could rearrange the furniture in my house and I wouldn’t notice. I believe my thoughts. So when things go counter to my expectations, I don’t always notice right away.

A potent example of this happened when I took in my once-feral puppy, Clara. She had grown up wild to the age of about 11 weeks; her mother had a litter of puppies in the woods and I and other people in the neighborhood were feeding the mother in hopes of catching and rescuing the whole family. The puppy came in my house – completely ignoring me and slipping past me through the door – because she heard my dogs barking. She started to engage with them and I closed the door behind her – captured! In the space of an hour she had accepted my dogs and me, too.

When Clara accepted me, I assumed that would extend to the rest of the human race. She was young and she had turned the corner very quickly with me. Plus, she was a puppy! Puppies are fun; puppies are joyful. Puppies return our love for them!

The next day I put her in my car to take her to the vet for an exam and vaccinations. On the way, I stopped at a friend’s house to show her my new puppy. My friend stuck her head in the car and Clara growled – and not a cute growl. But I didn’t believe what my ears heard! I encouraged my friend to look in again and reach her hand out. This was met with louder and lower growls. Yikes!

That’s what it took to make me let go of my “puppy” preconception. I finally noticed that this puppy was extremely uncomfortable and doing rather un-puppyish things.

Clara’s extreme case forced me to learn and relearn this lesson: Perceive the actual dog in front of you, instead of your preconceived idea of the dog in front of you. I have become more observant because of her!

But you don’t need a feral puppy to make this mistake. When you plan an outing with your dog that you’re sure she’ll like, how long does it take you to notice if she is not enjoying it?

If you’re like me, you might have had a picture all fixed in your head of the wonderful time you were going to have together. It can sometimes take a while to notice that your beloved dog is not happy. She may not like the noise or the water or the other dogs or whatever and she has been trying to drag you back to the car. Oh! There is a real dog here on the end of my leash, and she’s not acting like the imaginary one in my head!

THE DOG IS OKAY

Interestingly, it works the other way as well. A dog might actually be okay when we assume she is distressed. I had this experience with my elderly dog Cricket after she developed canine cognitive dysfunction. Dementia, in humans and in dogs, is a tragedy. It is terrible and heartbreaking to see your loved one’s cognitive functions fail. My Cricket did go through what appeared to be a period of anxiety in the early and middle stages of her dementia. But she was fortunate because as the disease progressed, she got less distressed, not more. But it took me a while to catch up with this and believe it.

For a long time, I would experience a wave of sympathy and grief when Cricket walked in circles, forgot what she had just done, or zoned out in a corner. But I came to believe, through careful observation and what we know of dog cognition, that she wasn’t suffering when she did these things.

Unlike me, she didn’t remember her former capabilities and grieve them. She didn’t show frustration or anxiety as the disease progressed. The dog in front of me was impaired, but she was actually doing okay.

2. See the good. This sounds simple enough. Most of us know the benefits of “seeing the good in the world” and looking on the bright side. But that’s not what I’m talking about. I’m not talking about attitudes or the big picture. I’m talking about the little picture.

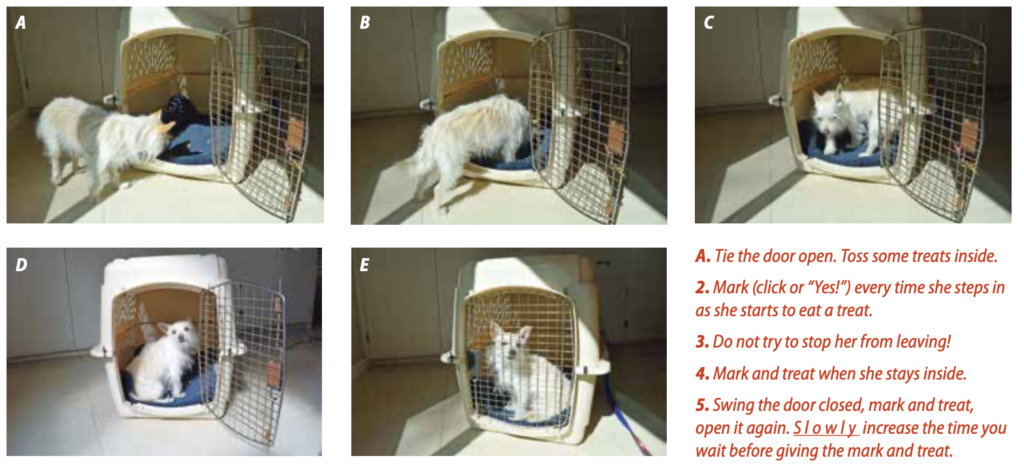

In positive reinforcement-based training, we set the stage for the behaviors we want. When our dogs perform them, we reinforce with food, play, and other things that work for that particular dog. But we have to see the behaviors first. We have to pay attention.

One method of developing a new behavior is capturing. With this method, we are on the lookout all the time for a behavior we want in a specific context. We look for the moment our dog bows, does a fold-back down, or checks in with us in a tough situation. We reinforce it. We are looking for what we want, rather than reacting to all the stuff we don’t want.

After a while, capturing can generalize – for the human! We aren’t looking for just that one behavior anymore. We notice all sorts of cool and helpful stuff that our dogs do.

It’s easy to notice the bad stuff; we are wired that way. It’s a survival issue. If our forebears missed seeing the stand of blackberries, the ripe pecans on the ground, or the excellent fishing hole, they might’ve gone hungry. Usually, however, they got another chance. But if they missed noticing the coiled snake or the rip tide – well, they weren’t anyone’s forebears.

This is not to say that positive reinforcement is flimsy. Far from it. We have to eat eventually, after we finish hiding from the tigers. We have to do it regularly or we die. It’s just that things that are dangerous or unpleasant grab us by the amygdala.

But I learned to notice when my dog did the right thing, the pleasant thing, or the safe thing. And this habit spread slowly to the rest of my life. I started noticing the good more, and that led to behavior change on my part. I not only noticed the good, but also encouraged it.

It meant going out of my way to say, “Thank you” – and not only in rote social situations, but in circumstances where a little observation told me that the person had gone out of their way to do something kind or helpful. It meant seeing common ground with difficult people. It meant sticking up for someone I disagreed with if they were arguing politely and fairly. It meant complimenting perfect strangers if I liked how they were interacting with their kids, their parents, or their animals.

Finally, it made me examine my values carefully. What is “good,” to me anyway? If I’m going to encourage people in certain behaviors, I’d better have thought things through!

3. Have patience with behavior change. I can remember the days when I thought I should be able to change my dog’s behavior instantly, if only I knew the right trick or could buy the right gizmo. Abracadabra, and the dog no longer jumps over the fence into the garden. There is some kind of disconnect in our culture about that. Because even if we haven’t heard of things like learning theory, positive reinforcement, or extinction, we are probably familiar with habits.

We know habits are hard to change – and I’m not even talking about addictions, just everyday habits! How long does it take you to consistently remember to take the new route to work because of the long-term construction happening on your usual route? What about that time four weeks into the new route when you were daydreaming and went the old way again?

How many times do you try to flip on a light switch when you know your power is out? How long does it take to change your posture because of your physical therapist’s instructions? To breathe differently?

Most adults have been bopped on the head by reality many times when trying to change habits. Yet we still can buy the idea that we should be able to change a dog’s behavior instantly when said behavior is currently working great for the dog. And even if we are taking our time to train the dog well and the dog is a happy participant – we are still working against habits.

What I have learned from dog training and behavior science and by paying attention is that changing an ingrained behavior can be slow. When I see how difficult it can be for me, it gives me more patience with my dogs (and with people, too!).

COMPLEMENTARY LESSONS

These three lessons enhance each other. Not being hampered by preconceptions (#1) helps me see the good in a situation (#2), and patience (#3) helps me shape the good that is already there into something better. This is true for dog training, people training, and my own personal growth.

Portions of this article were first published in BARKS from the Guild, Pet Professional Guild’s official publication.