Dog trainers often recommend smartphone apps and YouTube videos for desensitizing and counter-conditioning dogs who are afraid of specific noises. There are many apps designed and marketed for this purpose, and they typically include recordings of many different sounds. However, the physics of sound production and the limitations of consumer audio present large problems for such use – problems substantial enough to prevent the success of many (most?) conditioning attempts.

WHY MANY AUDIO CONDITIONING PRODUCTS FAIL

If quizzed, most people would likely guess that dogs have hearing abilities that are vastly superior to ours. In fact, it’s a mixed bag.

Humans can hear slightly lower frequencies than dogs can, and we can also locate sounds quite a bit better. But dogs are the big winners in the high frequency range; they can hear tones over about twice the frequency range that humans can. Also, dogs can hear sounds at a much lower volume level than humans can over most of our common audible range. Yet the superior aspects of dogs’ hearing are rarely considered when we decide to use sound recordings in conditioning!

There are four major acoustical problems with using human sound devices to condition dogs:

• The inability of smartphones to generate low frequencies, such as those present in thunder.

• The limited ability of even the best home audio systems to generate these low frequencies in high fidelity.

• The upper limit of the frequencies generated on all consumer audio.

• The effects of audio file compression on the fidelity of digital sound.

There are also common problems with the use of sound apps that can be deduced through what we know through behavior science. These can also make or break attempts to positively condition a dog to sound:

• Lack of functional assessment before attempting conditioning.

• The length of the sound samples used for conditioning.

• The assumption that lower volume always creates a lower intensity (less scary) stimulus.

Some, but not all of the above problems can be addressed with do-it-yourself work and a good plan. But sound conditioning of dogs using recordings will always have some substantial limitations that can affect success.

WHAT IS THE FREQUENCY?

Frequency is the aspect of sound that relates to the cycles of the sound waves per second. Cycles per second is expressed in units of hertz (Hz). I’ll refer a lot to low and high frequencies because they pose different challenges.

To help with the concept of frequency, think of a piano keyboard with the low notes on the left and the high notes on the right. The low notes have lower frequencies and the high notes have higher frequencies. Keep in mind that sound frequency goes much higher than the highest notes on a piano!

Common sounds with low frequencies include thunder, fireworks, industrial equipment, the crashing of ocean waves, the rumble of trains and aircraft, and large explosions. Common sounds with high frequencies include most birdsong, the squeaking of hinges, Dremels and other high-speed drills, referees’ whistles, and most digital beeps.

Motorized machinery generates sound frequencies that correspond to the rotation of the motor. These frequencies can be high like the dentist’s drill or low like aircraft. Motors can also vary in speed. For instance, when you hear a motorcycle accelerating, the frequency of the sound rises as the engine speeds up.

Humans can hear in a range of 20 to 20,000 Hz, and dogs can hear in a range of 67 to 45,000 Hz.

Some sounds don’t have a detectable pitch, meaning they include such a large number of frequencies that you can’t pick anything out and hum it. These are called broadband sounds. A clicker generates a broadband sound.

FRIENDS IN LOW FREQUENCIES

Our human brains are great at filling in blanks in information and taking shortcuts. This makes it hard for us to realize what a bad job our handheld devices do in generating low-frequency sounds. Our dogs undoubtedly know, though.

Many people purchase sound apps in order to try to condition their dogs to thunder. The frequency range for rumbles of thunder is 5 to 220 Hz. Handheld devices generally have a functional lower output limit of about 400 to 500 Hertz. If you play a recording of thunder (or a jet engine or ocean waves) on a handheld device, the most significant part of the sound will be played at a vanishingly low volume or be entirely missing.

When performing desensitization, we aim to start with a version of the sound that doesn’t scare the dog, so this could possibly be a starting point. On the other hand, without the distinctive low frequencies that are present in real thunder, some dogs will not connect the recording (played at any volume) with the real thing.

Home sound systems, including some Bluetooth speakers, can do a better job. They usually generate frequencies down to 60 Hz. This is roughly the lower limit of dogs’ hearing, so it’s a good match. But even the best home system can’t approach the power and volume of actual thunder, and the sound is located inside your home instead of outside. Some dogs do not appear to connect recordings of thunder on even excellent sound equipment to the real thing, or they will respond to recordings with a lesser reaction.

In one study of thunder phobic dogs, the researchers brought their own professional quality sound system to each dog owner’s home; great mention is made of the fact that the sound system was large. This bulk indicates that they were serious about being able to generate low frequencies! In general, the larger the speakers, the better they are at generating low frequencies. The difference today is smaller than it was 15 years ago, however. Sound systems have improved a lot in recent years.

Some of the sound apps for dog training now instruct you to send the sound to a home sound system rather than using the speaker in the handheld. This is excellent advice for any sound. But the bottom line is that you will not always be able to emulate low frequencies well enough to function as desensitization for some dogs.

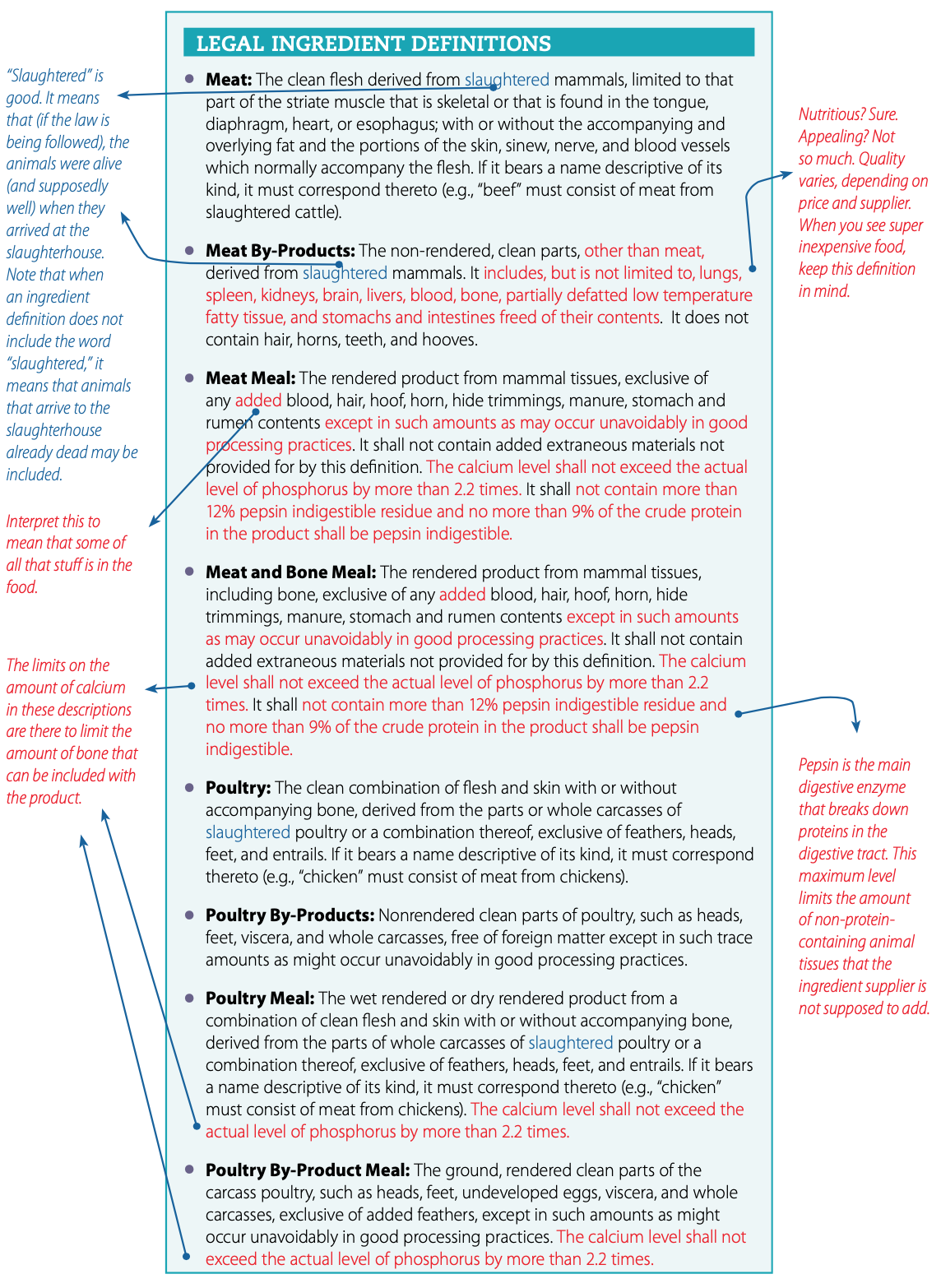

Table I (at left) shows the difference between the sound of a roll of thunder played on an iPhone 7 versus a home sound system (Altec Lansing speakers). The Blue Yeti microphone I used to capture the sound for analysis was the same distance from the speaker in each case.

The graph in the oval is the approximate range of the rumbles of thunder. The navy blue line represents the sound generated by the smartphone in those frequencies. The red line was from the Altec Lansing home speakers. The speakers generate sound down to 60 Hz (as per their specifications).

In contrast, the output of the phone is virtually inaudible below 300 Hz.

LET’S GET HIGH FREQUENCIES

All consumer audio equipment is designed for human ears. Our handhelds, computers, TVs, and sound systems put out sound only up to the frequency of 22,000 Hz. Humans can’t hear higher frequencies than that. But dogs can hear up to about 40,000 Hz. So again, the recordings are not high fidelity for dogs.

This is different from the thunder situation. The low frequencies of thunder are present in high quality recordings, but our equipment can’t perfectly generate them. With high frequencies, it’s not only a limitation of our speakers. The sounds in “dog frequencies” are not recorded in the first place.

It’s not that it can’t be done. Biologists and other scientists use specialty equipment that can record and/or play back sound in the ultrasound range. The recording device requires a higher sample rate (how often the sound is digitally measured) than consumer equipment and the speaker for playback requires a wider bandwidth for frequency response.

How much does this affect the fidelity of recorded sound for dogs? We can’t know for sure. But virtually all sounds include what are called harmonics or overtones. These are multiples of the original frequency into a higher range. Dogs can hear these in the range from 22,000 to 40,000 Hz, but they are never present in sound recordings made even by very high quality equipment.

Because of this, it’s likely that dogs with normal hearing will be able to easily discriminate between a natural sound and even the best recording of it.

SOUND FILE COMPRESSION

Digital audio files are large. Most files that are created to play on digital devices are saved in MP3 format. This format was created in the 1990s when digital storage was much more limited than it is today. Hence, MP3 files are compressed, meaning that some of the sound information is removed so they won’t be so large.

MP3 is termed a “lossy” compression because sound data is permanently lost through the compression. The compression algorithms are based on the capabilities of the human ear. Sounds we humans are unlikely to be able to hear are removed.

Some of these limitations may be shared by dogs. For instance, quieter sounds that are very close in time to a loud sudden sound are removed. We can’t hear those because of masking effects, and it’s probable that dogs can’t either, although there may be a difference in degree.

However, there are other limitations of the human ear that dogs do not share. For instance, our hearing is most sensitive in the range of about 2,000 to 5,000 Hz, so very quiet sounds that are pretty far outside that range will likely be eliminated. Dogs’ most sensitive range is higher than ours, so sounds they could hear are probably omitted from compressed recordings.

Keep in mind that dogs not only hear sounds that are higher than we can perceive, but they hear all high-pitched sounds at lower volumes than we do.

So the MP3 compression process is another reason that some sounds in dogs’ hearing range that would be present in a natural sound would be missing in a recording of it.

If you make your own recordings, there is an easy thing you can do to prevent this issue: Simply save your sound files in WAV or AIFF formats as discussed below. I haven’t seen a desensitization app that uses these formats, however.

BEHAVIOR SCIENCE CONSIDERATIONS

The problems I’ve discussed so far are caused by the physics of sound and how it is recorded, compressed, and played.

The following cautions have to do with applying what we know about performing classical conditioning to sound without errors.

- Lack of Functional Assessment

Trainers who deal with dogs with behavior problems perform functional assessments. They observe and take data to help them understand what is driving the problem behavior. In the case of fear, they analyze the situation in order to determine the root cause of the fear.

In the case of sound sensitivity, a dog may react because the sound has become a predictor of a fear-exciting stimulus, as is the case with much doorbell reactivity. Or the dog may be responding to an intrinsic quality of the sound, in the case of sound phobia. Sound phobia is a clinical condition that requires intervention. Many such dogs need medication in order to improve.

Trainers, working with veterinarians or veterinary behaviorists, can make these determinations. Consumers often can’t. And as the sound apps being marketed to consumers become more elaborate, pet owners who follow the directions have a good chance of worsening some dogs’ fears.

For example, a newer sound app allows you to set up the app to play the sound randomly when you are not home for purposes of desensitization (without counter-conditioning). The instructions show an example of a dog’s doorbell reactivity going away through use of the app (although perhaps not permanently). The app was programmed to play doorbell sounds randomly when the owner wasn’t home. This decoupled the doorbell as a predictor of strangers at the door.

This protocol would give any professional trainer pause. First, the cause of the reactivity – the dog’s fear of strangers – wasn’t addressed at all. All things considered, that is not a humane or robust approach. The dog’s fear is left intact while the inconvenience of their barking at predictors is removed. Second, the instructions of playing a feared sound randomly when the owner isn’t home, even at a low volume (more on this below) could result in a ruinous situation for a dog with a true sound phobia rather than “just” doorbell reactivity.

Apps that can play randomized, graduated sound exposures can be a good tool for trainers, as long as the trainers are aware of the limitations here. They should not be marketed or recommended to consumers.

- Length of the Sound Stimulus

Many noises in the apps are too long for effective desensitization and counter-conditioning. Real-life thunder and fireworks both have an infinite array of sound variations. If you play a 20-second clip of either of these, there will be multiple sounds present and a sound phobic dog may react several times, not just once.

Classical delay conditioning, where the stimulus to be conditioned is present for several seconds, and the appetitive stimulus (usually food) is continually presented during that time, is said to be the most effective form of classical conditioning. This is the method that trainer Jean Donaldson, founder of the well-regarded Academy for Dog Trainers, refers to as “Open bar, closed bar.”

Delay conditioning would be appropriate to use for a continuous, homogeneous sound, such as a steady state (non-accelerating) motor. But fireworks and thunder are not continuous; they are sudden and chaotic. They consist of multiple stimuli that can be extremely varied.

To offer a visual analogy: If your dog reacts to other dogs and you seek to classically condition him, you might create a careful setup wherein another dog walks by at a non-scary distance and is in view for a period of, perhaps, 10 to 20 seconds. You would be feeding your dog constantly through that period. That is a duration exposure to one stimulus. (And you would try to use a calm decoy dog who doesn’t perform a whole lot of jumpy or loud behaviors!)

But for the first time out you would not take your dog to a dog show or an agility trial to watch 60 different dogs of all sizes and shapes coming and going and performing all sorts of different behaviors, even if you could get the distance right and the exposure was 10 to 20 seconds. That is the visual equivalent of the long sound clip of fireworks. There are far too many separate stimuli!

Also, if you play a longer clip, one lasting many minutes (as has been done in some sound studies), you are essentially performing simultaneous conditioning, a method known for its failure to create an association. The fact that you started feeding one second after the sound started is not going to be significant if the crashes of thunder and food keep coming for minutes on end. You have not created a predictor.

And if you are feeding the whole time but the scary sounds are intermittent, you are probably also performing reverse conditioning, where the food can come to predict the scary noise.

If you are working to habituate a non-fearful dog or a litter of puppies to certain noises, the longer sound clips are probably fine for that. They may even work for a dog with only mild fears of those noises. But the more fearful the dog is, and the closer he is to exhibiting clinical noise phobia, the cleaner your training needs to be. To get the best conditioned response, you need a short, recognizable, brief stimulus.

After you get a positive conditioned response to one firework noise, for instance, you can then start with a different firework noise. After you have done several, you may see generalization and you can use longer clips. But don’t start with the parade!

- Volume

Most mammals have what is called an acoustic startle response. We experience fear and constrict certain muscles when we hear a loud, sudden noise. It’s natural for any dog to be startled by a sudden noise. It may be that dogs who have over-the-top responses to thunder and fireworks have startle responses so extreme as to become dysfunctional. For dogs who fall apart when they hear a sudden, loud sound such as thunder, it makes all the sense in the world to start conditioning at low volume, because this practice can remove the startle factor.

But it’s different for dogs who are scared of high-frequency beeps and whistles. These odd, specific fears are not necessarily related to a loud volume. I have observed that, with these dogs, starting at a quiet level can actually scare the dog more. Remember, dogs don’t locate sounds as well as humans do. It could be that the disembodied nature of some of these sounds is part of what causes fear. (Have you ever tried to locate which smoke alarm in a home is emitting the dreaded low battery chirp? Even for humans, it can be surprisingly difficult – and we are better at locating sounds.)

When lowering volume is ruled out as a method of providing a lower intensity version of a sound stimulus, virtually all apps for sound desensitization are rendered useless.

SOLUTIONS

With apps that can do more and more for humans, it seems odd to suggest that in order to help your dog, you might have to invent your own helpful tools. But doing so can help you make recordings of better fidelity and more appropriate length, and if you (or an acquaintance) are at all tech-savvy, you can also alter sounds in other ways besides volume.

- Record sounds yourself using an application that can save the recordings in WAV or AIFF (uncompressed) formats. This eliminates one of the ways that recordings can sound very different to dogs from real life sounds. Newer smartphones are fine for this. Even though they can’t play low frequency sounds, they can record them.

- Create short recordings of single sounds, especially for dogs with strong sound sensitivities. Or, purchase sounds and edit them down. For instance, you could purchase a 20-second recording of a thunderstorm, and edit out one roll of thunder to use. But be sure that the file you purchase is uncompressed.

- Play sounds for desensitization on the best sound system possible, especially if you are working with thunder, fireworks, or other sounds that include low frequencies.

- For dogs who are afraid of high-pitched beeps, create a less scary version by changing the sound’s frequency or timbre rather than by lowering the volume. Generally, lowering the frequency works well. You will then need to create a set of sounds for graduated exposures. They should start at a non-scary frequency, then gradually work back up to the original sound.

There are several ways to change the frequency of a recorded sound. You can use video software that has good audio editing capabilities, the free computer application Audacity, or professional sound editing software. You can also generate beeps at different frequencies using a free function generator on the internet.

The one advantage of working with dogs who are afraid of such sounds is that the original sounds themselves are usually digitally generated, so when you create similar sounds the fidelity will be high. (In other words, when a dog is afraid of a smartphone noise, a smartphone is the perfect playback tool.)

HEAR ME OUT

This is not a project to be undertaken lightly, but it can be done if you have tech skills and a good ear. Be sure to use headphones and be at least one room away from your sound-sensitive dog when you start working with recordings of beeps. My dog can hear high-frequency beeps escaping from my earbuds from across the room!

Be aware that with some dogs and some sounds, it will not be possible to play recordings that are similar enough to the natural sounds to be able to carry over a conditioned response. Thunder and fireworks will always present significant problems.

We want to believe that there is always a training solution. But sometimes physics foils our plans and the gap between an artificially generated sound and the generated sound will be too high. In that case, masking, management, and medications will be the best help.