Digestion involves the balanced interaction of several biodynamic systems. A healthy animal ingests raw materials (food), changes these raw materials into usable nutrients, extracts from these nutrients the essentials for life and vitality, and excretes (in the form of feces) those substances that have not been digested or that weren’t utilized.

The entire process of digestion is the result of many organs and systems, but for this article we will concentrate on the digestive tract, beginning with the mouth and esophagus, proceeding downward through the stomach, then through the intestines, and finally passing out through the rectum.

Notable components of the digestive system that will not be covered in this article but will be discussed in later articles include the liver and pancreas. On the other hand, we will discuss three “organ systems” that are essential components of the digestive system (but that are not typically thought of as such by conventional Western medicine): 1) the immune system, 2) the nervous system, and 3) the dynamic population of “bugs” that live in the gut.

GI Anatomy in Dogs

The mouth and its related structures (see “Your Dog’s Mouth” to learn more about it!) form the beginning of the “tube” where digestion occurs. The dog has several salivary glands located around the jaw and mouth. In humans, saliva plays an important part in digestion by providing the enzyme, amylase, which converts starch to the simple sugar, maltose. Saliva of the dog (and cat), however, has no enzymatic activity of note. Its functions include lubricating the passage of food to the stomach and moistening the oral mucous membrane. In addition, saliva aids in heat loss for dogs; salivation increases dramatically as the ambient temperature rises.

The esophagus is a muscular tube that propels the food bolus, after swallowing, from the mouth into the stomach. The act of swallowing begins when the animal uses its tongue to push the food to the back part of the mouth, where the upper esophageal sphincter relaxes to allow passage. At the same time, the epiglottis closes over the opening to the trachea, halting respiration for a moment and preventing food from being passed into the lungs.

Once in the esophagus, the food is moved to the stomach by automatic peristaltic activity. Peristalsis is a wave of muscular activity that passes through tubular organs – including the esophagus and the intestines – in a wormlike fashion, forcing substances within the tube to move steadily from the beginning of the tube to its terminus. As the food reaches the stomach, the lower esophageal sphincter relaxes to allow passage into the stomach. After food passage, this sphincter is closed to prevent reflux of the stomach contents.

Digestion begins in the stomach, a thick-walled, muscular organ where food can be stored long enough to be mixed with gastric juices. These juices are mucoid, highly acidic, and contain pepsin (a protein-digesting enzyme) and gastrin ( a hormone that controls the digestive process via feedback mechanisms).

The canine stomach is adapted to accept huge quantities of food in any single session. It can create extra space by relaxing the muscular fibers in its walls and “unfolding” into a large reservoir where the food is churned and mixed before it is passed through the terminal part of the stomach (the pylorus) into the small intestine. The partially digested food, combined with gastric juices, is termed chyme (from the Greek chymos, juice), and is creamy and gruel-like.

How Do Dogs Digest Differently?

The dog’s digestive tract is quite different from ours. In the dog, partially digested foods spend a far greater amount of time in the stomach (some four to eight hours, compared to a half hour or so in humans). Then, the dog’s relatively short intestinal tract usually allows foods to pass through in much shorter times, although transit times vary widely in both species depending on the composition of the food.

The digestive activity of the stomach is also controlled by the composition of the meal and neural and hormonal controls. In the healthy animal all these work in harmony to produce an ideal inner environment conducive to complete digestion. Commercially prepared, highly processed food hinders normal digestion, since it does not resemble the diet the dog’s digestive system has, over eons, been adapted to use. Many drugs also alter the digestive process. Stress, too, can change digestive patterns, sometimes producing diarrhea and/or vomiting.

Chyme enters the small intestine where further digestion takes place and where most of the absorption of nutrients occurs. The small intestine is comprised of three segments (duodenum, ileum, jejunum). Each has a slightly different structure and function, but their overall function is to complete digestion so that absorption can occur.

A duct from the liver and one from the pancreas terminate near each other in the beginning area of the duodenum. The duct from the liver supplies bile (also called gall), which alkalinizes the intestinal contents and plays a major role in fat absorption by dissolving the products of fat digestion.

The pancreas has two major functions, divided into the exocrine and endocrine portions. Pancreatic exocrine function secretes acid-neutralizing bicarbonate and several digestive enzymes. The endocrine pancreas supplies hormones that circulate throughout the body and help control metabolism. Glucose is the endproduct of the nutrients that are destined to produce energy, and its metabolism and distribution to various body parts is under control of the pancreatic hormones. A lack of (or inadequate usage of) one of these hormones, insulin, results in diabetes mellitus.

After the nutrients have reached the small intestine, they are absorbed through numerous fingerlike folds called villi, which are in turn covered with millions of tiny microvilli. The microvilli perform multiple functions, including producing digestive enzymes, absorbing nutrients, and blocking absorption of waste products.

Protein digestion cleaves long chains of amino acids into individual amino acids, which are absorbed into the intestinal veins and then transported to the liver where they are further processed for use by the body.

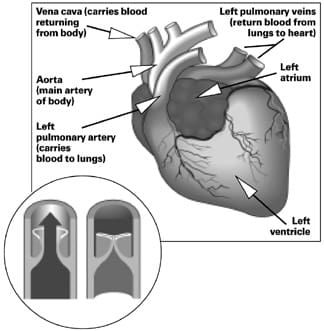

Chyle, a milky fluid consisting of lymph and droplets of triglyceride fat (chylo-microns), is taken up by the intestinal lymphatic system during digestion. Chyle passes into veins (via the thoracic duct) where it is mixed with blood.

Together, the large intestine (colon) and rectum comprise a much shorter segment of the digestive tract than the overall length of the small intestines. There are no villi for absorption in the colon; its surface is lined with mucous-secreting cells.

The main function of the colon is to act as a reservoir for storage; there is almost no active digestion in the large intestine except that done by the intestinal bugs. Absorption there is limited to fluids, electrolytes, fatty acids (produced as the bacteria ferment dietary fiber), and vitamins A, B, and K. To allow for storage time so there will be complete absorption of fluids and electrolytes, peristaltic movement through this portion of the intestine is slowed by segmental gut wall contractions.

The principal stimulus for motility in the large intestine is distention by its contents, the undigested material entering the colon. Colon contents stimulate both the segmental contractions that limit the speed of transit and the propulsive peristaltic activity that speeds transit time. Thus, paradoxically, adding bulk (fiber) to the diet is beneficial for treating both diarrhea and constipation. (With diarrhea, adding bulk to stimulate segmental contractions slows transit time and allows more complete absorption. With constipation, increasing bulk will stimulate mass propulsive activity necessary for fecal evacuation.)

Common Diseases of a Dog’s Digestive Tract

I’ll discuss the most prevalent diseases of the GI tract by the site of disturbance.

Salivary glands

These glands are not a common site for disease, but they can be affected by inflammation that is either primary or that occurs as a consequence of other diseases such as distemper or other viruses. Trauma may produce swelling, which typically goes away on its own. Sometimes, after trauma or foreign body penetration, one of the dog’s glands fills with mucous and saliva, producing a dramatic swelling that needs to be drained surgically. Tumors of salivary glands do occur, but they are rare.

Esophagus

There are several rather uncommon abnormalities of the esophagus, including esophageal dilatation, idiopathic mega-esophagus, and esophageal stenosis/stricture. Symptoms of these diseases may vary, making accurate diagnosis difficult; surgery may be indicated for severe conditions. Some cases may respond to diet changes and/or alternative treatments.

Inflammation of the esophagus is frequently due to gastric reflux (often from persistent vomiting), but it may also be instigated by anesthesia or other drugs. Conventional Western medicine will treat severe cases with antibiotics, steroids, and drugs to stop the vomiting. Alternative practition-ers might use herbs and acupuncture to soothe the tissues and for their antibiotic and immune-enhancing activities.

Foreign bodies – bones, needles, fishhooks, wood splinters, etc. – are a relatively common occurrence in the esophagus; radiographs may be needed to diagnose their presence. They may cause salivation, vomiting, gagging, and reluctance to eat. Whenever possible, esophageal foreign bodies should be removed (by your veterinarian) through the mouth via an endoscope or speculum. If this is not possible, surgery may be necessary. Whatever the method of removal, consider using herbal remedies to help combat inflammation.

Stomach and intestines

Gastritis (inflammation of stomach) and enteritis (inflammation of the intestines) offer a panoply of diseases, caused by the usual culprits: bacterial, viral, fungal, protozoal, traumatic, and neoplastic diseases. For the holistic practitioner, almost all these can be lumped under the general term “dysbiosis” (from two Greek terms “dys,” meaning bad, abnormal, or difficult; and “bios,” meaning life or living organisms). The term seems to fit almost all the digestive problems seen in dogs; treatment protocols for dysbiosis are discussed below.

Of special interest are viral disease complexes that affect the intestines, including parvovirus, distemper, and coronaviral gastroenteritis – highly contagious diseases that can be severe, especially in puppies. Symptoms vary with the disease and its severity, but typically include diarrhea (possibly severe) and perhaps vomiting. Vaccines are available for the viral diseases mentioned above; their safety and efficacy are topics for discussion another day.

The large intestines can also be infected, although rarely, with a myriad of microorganisms, parasites, and mechanical disorders. The most common symptom is diarrhea. Conventional Western medicine uses a variety of drugs to control the diarrhea; holistic treatment concentrates on returning the bowel microflora to normal.

IBD and Leaky Gut Syndrome

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) and “leaky gut” have received recent notoriety, perhaps because we see so many cases today. Most of my holistic practitioner friends believe this is a direct result of changing our dog’s diets so drastically over the past 50 years. Both of these disease complexes involve a compromised immune system that in turn creates a chronic dysbiosis in the gut.

In healthy digestion, proteins are broken down into amino acids that can be absorbed into the bloodstream; large particles of protein are held in the lumen of the gut until they can be fully digested. With the leaky gut syndrome, the cells of the gut wall loosen their normally tight attachments, and food proteins are absorbed before they are fully broken down. The body’s immune system regards these proteins suspiciously, and classifies them as foreign invaders, inciting the immune system to react to fend off the “invaders.”

Leaky gut syndrome can be instigated by a number of factors: food allergies, Candida overgrowth (most often from excessive antibiotic or steroid use), or stress. Symptoms can be highly variable; many chronic diseases such as arthritis, skin and other allergic disorders, and fatigue and malaise have been attributed to a leaky gut.

Inflammatory bowel disease is also due to an immune system gone awry. IBD has many of the same symptoms as leaky gut, with perhaps a more profound immune system response. Either of these diseases may predispose the patient to the other disease, and both can become chronic.

Conventional treatments for leaky gut and IBD include antibiotics, and interestingly, steroids or other drugs that shut down the immune system. Holistic practitioners, in contrast, will try to balance the immune function of the digestive system by encouraging a normal flora and by providing immune-enhancing treatments such as herbs and acupuncture.

Specific treatment protocols for either of these diseases will, of course, vary for the individual case, and treatments are too complex to be discussed in depth here. In my clinical experience, I’ve relied on the general protocol for dysbiosis below, adapting it for each individual.

A common misconception when treating either IBD or leaky gut is that you can effect a cure simply by changing the diet – from beef to an exotic protein source, such as kangaroo or ostrich. While diet changes may be effective for the short term, an unhealthy digestive tract will eventually react to (and may become allergic to) whatever protein it is exposed to most. Long-term healing will always rely on returning the gut to health. Re-establishing a healthy, more natural gut microflora is the one necessary step common to all cases of dysbiosis.

Harmful GI Parasites

There are hordes of gastrointestinal parasites that infest the digestive tract, from the mouth to the anus. While some of these can cause severe problems, for the most part they are easily controlled with commercially available drugs. Holistic practitioners tend to look at internal parasites as another cause of intestinal dysbiosis; our challenge is to keep the parasite load to a minimum (it is not always in the best interests of the animal to eliminate all parasites) without using medications that may be toxic. We will discuss nontoxic parasite control in a later article.

Ulcers in Dogs

Ulcers are not a common problem in dogs, but to me, they represent much of what is wrong with current-day, Western medical thinking. There’s been a big push lately to put the blame for ulcers on one bacterium, Helicobacter pylori, thus making it easy to effect a “cure” with antibiotics.

There are several problems with this approach. First, while H. pylori can be isolated from most (human) patients who have ulcers, there are a percentage of patients (30 percent or more) who have ulcers without the presence of the bacteria. Second, H. pylori can be isolated from many perfectly healthy individuals. Third, animal studies (dating back to my early days as a pathologist) indicated that it is almost impossible to infect an animal with H. pylori and produce ulcers, unless the animal is concurrently stressed. Stress, of course, almost certainly plays a role in producing ulcers, if it is not the primary cause.

Despite all this scientific evidence, apparently it is far easier to sell a magic bullet treatment (antibiotics that kill H. pylori) than it is to get folks to look for long-term, holistic ulcer preventatives, or to lower the stress levels in their dogs’ lives.

A cynical view would suspect that the antibiotic-producing drug companies have spun the scientific findings to enhance their bottom line. Of far more concern than all this, however, is the fact that H. pylori is a bacteria that mutates rapidly when it is exposed to antibiotic pressures, much more rapidly even than most other bacteria. So, we have a very rapidly mutating bacterium, to which Western medicine responds with newer and better antibiotics, to try to keep up with the mutations. Who knows what evil ogre of a Frankenstein bacterium we will ultimately produce with our inappropriate overuse of antibiotics?

Gastrointestinal Tumors

While neoplasia (tumors) are relatively rare, they may occur anywhere throughout the GI tract. Symptoms will depend on the severity and location of the tumor; X-rays and/or biopsy may be required for proper diagnoses. Lympho-sarcoma may create an infiltration of lymph cells throughout most of the length of the gut wall, thereby making nutrient absorption nearly impossible.

Some neoplasias, notably lymphosarcoma and mast cell tumor, may respond to chemotherapy. Surgery may be indicated for nodular or well-circumscribed tumors. Holistic practitioners use a variety of methods to treat neoplasia, including homeopathy, acupuncture, and herbal remedies.

Anal Sac Problems

Anal sacs are two structures located slightly below and lateral to the anus. Their function is unknown, although many veterinarians believe that some evil entity created the pox of anal sacs as a way to aggravate veterinarians and to befoul their exam rooms with what I consider the most noxious and fetid odor on this earth – and I am a pathologist, accustomed to all sorts of obnoxious aromas.

Anal sac disease is the most common disease entity of the dog’s anal region. Small breeds are predisposed. Large or giant breeds, and in my experience, “country” dogs that are able to roam over some range are rarely affected. The disease can result in impaction, infection, or abscesses.

Conventional medicine treats anal sac problems with the usual antibiotics and glucocorticoids or surgery if severe. The conventional recommendation is also to manually express the sacs periodically, supposedly to keep them cleaned out. However, I am convinced that proper exercise and a more natural diet will virtually eliminate most, if not all, anal sac problems.

Dysbiosis and Treatments for Dogs

The term dysbiosis seems to fit almost all the digestive problems seen in dogs. From the holistic perspective, nearly all problems that arise in the digestive tract are best treated, long term, by remembering that symptoms are a signal that something bad has happened to the living organism (and especially to the trillions of living organisms, the helpful flora of the gut); something abnormal has made their lives difficult or impossible.

Also, keep in mind that all animals, but particularly the dog, have an amazing inner ability to maintain their own system in eubiosis (“eu,” from Greek meaning well or good; the opposite of “dys”). Dogs seem especially well adapted for coping with all sorts of intestinal insults. Think here of the ancient dog whose diet often consisted of decaying meats, and the more recently domesticated dog whose diet has been (until 50 to 100 years ago) whatever was left over from the human table – fish heads, animal guts, and scraps of meat, fat, and bone.

Our modern dog evolved a tremendous capacity for dealing with meats, fats, and decaying matter; its digestive system is set up to allow for natural detoxification.

As we have seen, compared to the human digestive tract, the dog’s is much shorter and transit time is thus shorter, which gives toxins much less time for exposure to the gut. In addition, the dog appears to have the ability to decrease intestinal transit time rapidly, allowing for some often dramatic bouts of transitory diarrhea. Dogs also seem to have the ability to vomit quite easily. (You and your rugs probably already know this.)

The bottom line is: Don’t get too excited if your dog pukes a few times, has a few bouts of diarrhea, or refuses to eat for a day or two. These are his natural methods of detoxification. The time to become concerned is when vomiting or diarrhea is severe, when either the vomitus or the stools are bloody, when he has a concurrent fever, or when either the diarrhea or vomiting has persisted for more than eight hours or so.

The basic steps I take when treating dysbiosis are as follows, and I’ll discuss each in turn below:

- Detoxification

- Soothing the intestinal tract

- Alternative therapies, including acupuncture, homeopathy, and herbal remedies

- Returning the gut to its normal microflora

- Maintaining a diet that is natural for the canine

1. Detoxifying your dog

Our world has become laden with toxins, many of which are carcinogens. Our dogs are exposed to an even higher toxic load than we are; their noses are constantly sniffing the ground, where toxins accumulate. We throw even more toxins into the mix every time we use pesticides or medications to kill internal parasites, and when we feed them foods heavy with artificial preservatives, colors, and flavors.

By the time they are a few years old, our pets have been so exposed to the plethora of toxins that exist in their (and our) world, I think every holistic, long-term health maintenance protocol needs to include an entry period of detoxification. Then, I believe all of us and our pets should undergo a mild detoxifying program several times a year, perhaps coinciding with the four changes of the seasons.

Detoxification programs vary somewhat, depending on the specific needs of the animal and the seasons. They should be used periodically, not daily. Following are some basic principles:

• Fasting: Give the body a chance to get rid of some of the junk that is swimming around in the gut and bloodstream. Remember that over thousands of years the canine digestive tract has become well-suited for the predatory lifestyle of long periods of “food famine,” followed by a kill, which provides a short-term glut of nutrients.

A periodic day or two of fasting is good for all of us, and it is especially beneficial for our canine companions. (Some of my holistic veterinary colleagues recommend a three- to five-day fast, several times a year.) You may want to include a mild herbal laxative before the fast, and be sure to make sure your dog drinks plenty of water during and afterward. Discuss the exact protocol with your holistic veterinarian.

• Detoxifying supplements and foods: Fiber and/or mild herbal laxatives stimulate peristalsis and encourage stools to pass quickly and easily. Bulk fibers such as psyllium husks, more potent herbal laxatives, and/or diuretics (to help detoxify via the kidney) may be recommended.

• Enhance healthy flora: The most important step. See below for more detail.

2. Soothing the intestinal tract

Demulcent herbs soothe and protect the digestive tract membranes. Demulcent herbs include marshmallow root (Althea officinalis), oats (Avena sativa), and slippery elm bark (Ulmus fulva).

Antispasmodic herbs relax any nervous tension that may cause digestive colic. These include chamomile (Anthemus nobile or Matricaria chamomilla), hops (Humulus lupulus), and valerian (Valeriana officinalis).

3. Nonconventional therapies

It’s been my experience that alternative and complementary medicines are extremely effective for alleviating almost all functional problems of the digestive system, and they cause far fewer long-term problems. The primary therapies I use for acute cases include herbs, homeopathy, and acupuncture (Traditional Chinese Medicine).

• I first look to herbal remedies for treating intestinal problems because they have such a wide range of specific activities. Also, they offer a mild and safe therapeutic input that will help harmonize a system temporarily out of whack. There are many categories of herbs that can be helpful; some of my favorites are listed below.

Carminative herbs contain volatile oils that affect the digestive system by relaxing the stomach muscles, increasing the peristalsis of the intestine, and reducing the production of gas in the system. Herbs in this category include cayenne (red pepper, Capsicum spp.); chamomile (Anthemus nobile or Matricaria chamomilla), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), ginger (Zingiber officinale), peppermint (Mentha piperita), and thyme (Thymus vulgaris).

For antispasmodic and demulcent herbs, see my comments above (under “Soothing the intestinal tract”).

There are several hepatic herbs that enhance the liver’s activity. Dandelion root (Taraxacum officinale), goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), wild yam (Dioscorea villosa), and yellow dock (Rumex crispus) strengthen and tone the liver. Cholegogues are herbs that increase the production of bile by the liver. These include artichoke leaves (Cynara scolymu), dandelion root, rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis), and turmeric (Curcuma domestica).

Laxative herbs include mild-acting herbs that enhance digestion, such as dandelion root, licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra), and yellow dock. More potent laxatives include cascara sagrada (Rhamnus purshiana) and senna (Cassia spp.). Antimicrobial herbs may be used when the cause of the upset is microbial, either bacterial or viral. Many herbs have broad-spectrum antimicrobial activity; some of my favorites for intestinal conditions include chamomile, echinacea (Echinacea spp.), Oregon grape root (Berberis aquifolium), and thyme.

Check with your holistic veterinarian or herbalist for dosages; these will vary according to the size of the animal, the type of delivery system used, and whether your dog needs a therapeutic or maintenance dose.

• Acupuncture/Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) fully appreciates the complexity of the GI system, and the TCM treatment for GI problems helps balance the interaction of several biodynamic systems.

According to TCM theory, the body’s energy or chi flows through meridians that pass thru the body, connecting specific acu-point locations.To treat an animal’s disease, an acupuncturist will place needles along the meridians to balance the flow of chi and thus produce health.

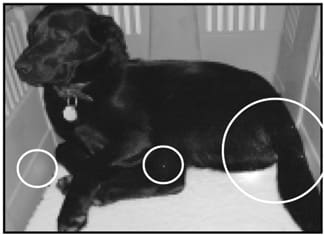

There are also easy-to-find points that anyone can activate (with a light-touch, circular massage directly on the point) to help create a balance in the digestive process. You can learn more about do-it-yourself acupressure in texts such as Four Paws, Five Directions, by Dr. Cheryl Schwartz; Veterinary Acupuncture, by Dr. Allen Schoen; and The Well Connected Dog: A Guide to Canine Acupressure, by Nancy Zidonis and Amy Snow.

Finally, if you want good healthy chi for your dog (or for yourself), you need to provide food that contains good healthy chi. Healthy food for dogs has vitality (is not overprocessed), is close to the canine’s natural diet, is fresh, and does not contain artificial additives.

• There are dozens of homeopathic remedies that are indicated for treating a variety of intestinal problems. Treating acute intestinal conditions is one example where I might use the acute approach to a homeopathic therapy. (See below.)

Perhaps the king of all remedies for vomiting is Nux v. Other remedies for intestinal upset include Arsen. alb. (for simultaneous vomiting and diarrhea); Ipec. (vomiting); Merc. sol. (pasty, non urgent diarrhea); Merc. cor. (straining with a forceful spurt of diarrhea); Rhus tox. (straining with bloody, mucoid, watery or frothy stools); Phos. (loose, yellow stool).

For acute cases (where the animal is otherwise healthy) a high potency is indicated (200c to 1X or higher, perhaps several doses, repeated every four to five hours during the first 24 hours). I have found the homeopathic remedies, when used in classical fashion (again, see below) to be very helpful for long-term therapy, especially when they are used in combination with other methods for re-establishing and maintaining a normal gut flora.

4. Returning the gut to its normal microflora

I hope that by now I’ve convinced you that a normal gut microflora is essential for maintaining your dog’s healthy gut and its active digestive system. And I hope you understand that antibiotics, glucocorticoids, inappropriate foods, an overload of toxins, and high levels of stress are all detrimental to the good-guy microflora.

In a perfect world, a dog’s intestines would naturally create an ideal environment for the growth of healthy microflora. Unfortunately, our dog’s world is not nearly perfect, and today’s realistic world creates a plethora of negative influences that adversely affect the gut’s microflora. With all these negative outside influences, it makes sense for us to try to recreate a healthy microflora by resupplying some or all of the healthy bugs a dog’s belly needs.

Unfortunately, there is no simple, single way to accomplish this. Since the gut flora constantly changes, depending on many factors including dietary intake, it is almost impossible to predict what kinds of bugs are needed. Plus, the microflora of the dog is likely very different from that of the healthy human, but most of the experimental work has been done on humans.

Many of the healthy bugs are destroyed in a highly acidic medium (that is, in the stomach), so, in theory, using the oral route to supply the bugs might not work, although surely in nature, ingestion of healthy microflora is the way animals obtained their healthy bugs.

Given these problems, here are some suggestions for supplying healthy micro-flora for your dog:

• Add small amounts of healthy micro-flora on a periodic basis, at least four or five times a week.

• Use a product that contains several different genera and species of bacteria; give the gut the most options possible.

• Use products that contain live and active cultures.

• Keep the product refrigerated, and make sure it has been refrigerated in the store. The bugs die quickly when not refrigerated.

• Don’t use sweetened products; the sugar only enhances the possibility for yeast overgrowth.

In order to simplify all this, I usually recommend using a good organic and unsweetened yogurt product, one that lists the bacteria on the label and one that claims their cultures to be “live” and “active.” It’s been my experience that, even though the bugs aren’t supposed to survive in the acid media of the stomach, dogs seem to have healthier guts when they are fed a dollop of yogurt every day or so.

5. Feed a natural diet

After you’ve helped your dog create a healthy gut environment, you can help maintain it with a good-sense diet. Consider that the canine’s intestinal tract has evolved to eat meats, fats, and rotting and decaying matter. The dog’s GI system is not prepared to process the refined carbohydrates most people feed their dogs, and it is certainly not functionally capable of utilizing or detoxifying the many synthetic substances it is exposed to today.

As the final step you can take to help insure intestinal health for your dog, consider a home-prepared diet.

“Acute” or “Classical” Homeopathy?

In acute homeopathy (as opposed to “classical homeopathy”), remedies are chosen to match the disease symptoms occurring at the time. Acute use implies that you are expecting to palliate (ease the symptoms) rather than to cure (treat and eliminate the deeper causes of the disease).

Conventional Western medicine’s drugs and methods typically palliate symptoms; seldom is any thought given to curing the deeper causes. Classical homeopathy, in contrast, selects a deeper remedy that matches the totality of the animal’s symptoms, which include the short- and long-term physical, mental, and emotional components of the dog, as well as the ongoing physical symptoms of the current disease crisis. Classical homeopathy requires taking an extensive history of the animal’s totality of symptoms, past and present. This in-depth intake alone may take an hour or more.

Interestingly, I have noticed that many of the patients I have the opportunity to treat classically (say, following up after an acute health crisis) seem to have a totality of symptoms that matches the remedy I had chosen to use acutely. In these cases, it is a simple matter to continue with the classical approach to remedy selection, after the initial acute dosing.

An example of this might be a vomiting dog that responds favorably to Nux v., and later is found by the diligent veterinarian who provides maintenance care to have many of the characteristics of a “Nux personality” – nervous, irritable, cannot bear noises or odors, sullen, does not want to be touched, has an “irritable” bladder, feels worse in the mornings, and may have periodic bouts of constipation and/or asthmatic-type coughing.

Three Extra “Organ Systems” Associated with the Digestive Tract

Intestinal microflora

Inside the intestines, mostly in the large intestine, resides a living mix of dozens of bacterial, viral, protozoal, and fungal species – billions of beneficial “bugs” in each gram of undigested material. Since the totality of this microflora engage in activities that enhance health and healing, these bugs are best thought of as a functional unit, or organ system, absolutely necessary for the well-being of the animal.

The most common bacteria in the large intestine include several species of Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium, along with high numbers of Streptococcal and Clostridial species and several types of lactobacilli. The total numbers of these helpful bacteria and the ratio of one species to another depend on the overall health of the intestines, and on other factors such as diet, local immune responses, levels of stress, and the use of drugs – particularly antibiotics and glucocorticoids.

The beneficial activities of the normal flora of the intestines are almost endless, but here’s a short list of the most important:

◆ Improve nutrient absorption

◆ Produce and enhance the absorption of several vitamins including vitamins A, B, and K

◆ Maintain the integrity of the intestinal tract and help protect against “leaky gut” syndrome

◆ Prevent and treat antibiotic-associated diarrhea

◆ Prevent the growth of disease causing microbes such as Candida spp., E. coli, H. pylori, and Salmonella

◆ Enhance the functional ability of the immune system

◆ Help acidify the intestinal tract, providing a hostile environment for pathogens and yeasts

◆ Help bind and either eliminate or prevent the absorption of a variety of food-borne toxins

◆ Evidence indicates that intestinal microflora may be protective against several types of cancer

In contrast, while your dog’s gut bugs naturally promote health, changes in the intestinal environment (with the use of antibiotics, for example, which indiscriminately kill most bacThree Extra “Organ Systems” Associated with the Digestive Tract teria, including the helpful ones) may cause the helpful bacteria to mutate into pathogenic (disease-causing) species. And, changes in the natural interrelationships – again, with drugs that upset the normal balance between bacterial species – may let other pathogenic bacteria gain a foothold in the gut.

Further, it should be noted that this “organ system” of helpful bacteria is in constant flux; the total numbers, activities, and the ratio of species varies constantly, depending on the dog’s diet, level of toxins and/or synthetic antibiotics presented to the gut, and levels of stress (or the levels of “synthetic/artificial” stress from glucocorticoid use).

Finally, it’s important to note that much of the experimental work on gut microflora has been done in the human species. It may not be appropriate to transpose all these data to our dogs, who are unfortunately undergoing a rapid transformation from their ancient, primarily carnivorous diets to today’s commercial diets, which are excessively high in carbohydrates.

Intestinal immune system

Current (human) research indicates that about 70 percent of the immune system is located in or around the digestive system. Called gut-associated lymphatic tissue (GALT), it is located in the lining of the digestive tract, especially in lymphoid-rich structures called Peyer’s patches. The system acts as a sentinel, on constant alert for foreign substances. It’s likely this is why so many of the chronic diseases we see in dogs can be traced back to the gut, back to something in the ingested foods that has overly-activated or otherwise interfered with natural immune functions.

Nervous system

The digestive system has its own nervous system, which can function on its own without the brain’s help. In this second nervous system, we can find every neurotransmitter that is found in the brain. “Gut feelings” can thus be very real, and when a dog is stressed, those feelings can profoundly upset the normal digestive processes. Calm dog; calm gut. Calm gut, normal and healthy digestion.

YOUR DOG’S DIGESTIVE HEALTH: OVERVIEW

1. Use safe, gentle herbal teas to help soothe and protect the GI tract.

2. Under the direction of your holistic veterinarian, occasionally fast your dog.

3. Several times a week, increase and enhance your dog’s GI microflora by feeding him organic, unsweetened yogurt containing live, active cultures.

Dr. Randy Kidd earned his DVM degree from Ohio State University and his PhD in Pathology/Clinical Pathology from Kansas State University. A past president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, he’s author of, Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Dog Care and, Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Cat Care.