by Caryl-Rose Pofcher

Hera is an nine-year-old spayed English Bulldog. Today I know to describe her as “reactive.” She has also been called aggressive, stubborn, willful, dominant, stupid, bad, and even conniving.

She is a “crossover dog,” meaning that we, her humans, started off using techniques that included jerking and pulling on her leash and collar, a choke collar, a prong collar, and even growling at her. Of course, we also used praise and some treats. Later, we “crossed over” to using only positive techniques and relied heavily on the clicker.

During the first four years of her life, when we used those earlier techniques, Hera became more reactive. She became faster to “launch” into a mindless fit of barking, growling, and pulling, more intense in her reactions. Although it was her reactivity to other dogs that we focused on, it wasn’t limited to dogs: roller bladers; skateboarders; bicycles; wheelbarrows; big trucks; buses; motorcycles; flags fluttering overhead; people walking past her with fluttery or dangly things like handbags, briefcases, long flowing skirts, or belts dangling from trench coats; an upstairs window opening as she walked past – and then there was the day she eyed an electric wheel chair! Squirrels weren’t safe from her attempts, nor was the occasional horse we’d see in parks or police horseback patrols.

I write this with a certain lightness of tone but make no mistake: Hera’s lunges were frightening. A Bulldog has muscle and strength, a low center of gravity, large chest, big head, big neck, and strong jaws with a large, tooth-filled mouth. She would lunge and snarl furiously. While engaged in these outbursts she displayed a glazed intensity that was frightening and potentially dangerous.

My husband, Billy, and I were the barely effective anchors at the end of her leash, preventing her from getting full speed and achieving her goals. Sometimes I would almost be knocked off my feet by her sudden sprint after something or other. On multiple occasions, in desperation, to stop being dragged forward, I hooked my arm around a parking meter or lamppost. My shoulder was wrenched many times. When in reactive mode, Hera, a 68-pound Bulldog, could and did pull me, a 115-pound woman, down the street almost at will. Those parking meters were part of my safety strategy!

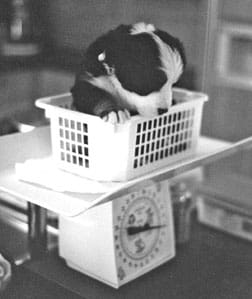

Unlike the typical phlegmatic image of the bulldog, Hera is agile, fast, strong, and athletic. And highly reactive.

How did this happen?

We started a 12-week puppy training class when Hera was 10 weeks old (it actually lasted 15 weeks because of a few interruptions in the schedule). We were told Hera was skittish, timid, stubborn, and fearful and that we had to show her we were in charge and expose her to a lot of new things.

To demonstrate these pronouncements, the assistant instructor once picked up a large dictionary and briskly walked straight toward us. As she approached, Hera turned her side to the approaching human and sidestepped back a bit. The assistant dropped the book to the floor with a great “slam,” inches from Hera, who skittered back and pulled to move away further. We were told to prevent her from getting further away and to ignore her.

Hera didn’t recover from that startle; she never came forward to curiously sniff the offending object, but continued trying to get away until the instructor finally said we could walk away with her.

In retrospect, I believe this and other events helped our skittish puppy learn that the world was not safe and that we, her humans, did not protect her.

We were the “bad apple” in puppy class, told by the instructor that we needed a choke collar and had to teach Hera who was in charge before it was too late. “Too late” raised dire images in our minds but we dared not asked for clarification, afraid we’d be told our beloved puppy was going to be a vicious monster. We were told her neck was very strong and we had to yank very hard in order to communicate with her.

We worked harder and followed instructions; Hera became harder to control, more apt to lunge, and less and less attentive to us. So we tried harder.

Hera knew how to “sit” prior to class. I’d read a dog training book and learned to lure her into a sit with a treat held over her head and moved back toward her tail. It worked quickly and was a game that we both seemed to enjoy. She loved to do “sit,” sometimes earning a treat or piece of kibble for the act, always earning praise. I looked forward to the class teaching us how to get a “down” in a similar fashion.

It didn’t happen that way. In class, we were told to teach “sit” by pushing on her butt and pulling up on the leash while saying “Sit.” We said she already knew. We were told she would now learn a new way. We were told to push. We pushed. She resisted. By the end of the class, “sit” had gone to hell in a handbasket!

We tried to obey our instructors, but a lot of what we were told to do felt wrong and uncomfortable to us, and so we complied erratically. Not surprisingly, Hera’s behavior became worse.

Hera always seemed excited about class, pulling to get inside, winding up as soon as we’d drive into the parking lot. On the way home, she was increasingly hard to control, lunging and pulling at every dog, a leaf blowing across our path, or a sudden sound.

At home she was our dear puppy, the love of our lives. However, we were disappointed she never snuggled. She stayed close but shunned curling up with us. She was also face shy and didn’t like grooming.

Hera was 25 weeks old at the end of the class. She had gained a great deal of strength and we had started to worry. She got her “diploma” but we also got a “look” when it was handed to us. We knew we had failed.

The owners’ education begins

Over the next few months, I started reading about dog behavior and training. My husband was happy to leave it in my hands. He was the one who wanted a dog in the first place, but this wasn’t what either of us anticipated! I think he was relieved that I took on the project.

I talked with the owners of Hera’s parents and learned that her father was equally reactive and reactive to similar triggers. His owners described him as “energetic and interested in everything.” But when I got details, and later watched them walk him down a city street, I saw he was highly reactive to most of the same triggers as our girl. He spent most of his life on a prong collar, kept on a short leash.

Hera’s mother exhibited reactivity less often, perhaps because in general she was a more sluggish dog. Her owners described her as “feisty” but only if something got close enough. Ah yes, Mom had a hair trigger when something was within her range.

I saw that we were probably dealing with a combination of genetics and our own lack of understanding. I started to seriously educate myself, becoming more selective about techniques I would use and would not use. As you’ll see, this education lead me on a life path I’d never anticipated.

Trying “teenage” times

At adolescence, Hera’s troubling behaviors outside the house intensified. She had been “the cute Bulldog puppy” at the dog park, but she soon became “that bad dog.” She had some spats, and would run across the dog park to jump on various dogs, snarling and growling when she reached them. We tried to identify trends in what would set her off, and thought we did see some, but there were exceptions to every “rule” we observed. She jumped some dogs who seemed to be minding their own business as well as dogs who seemed to be approaching her. She ignored other dogs who seemed to be minding their own business and some who seemed to be approaching her.

The good news was that she had good bite inhibition; she never broke the skin of the other dog. (She did, however, knock them down and mouth them, looking for all the world like she was tearing their throats out.) And often she played with other dogs, wrestling, taking turns being on top or bottom, mouthing gently and being mouthed. She chased and was chased, but generally couldn’t keep up with the longer-legged pups. She had favorite playmates at the park, a German Shepherd Dog pup who would drag her around by her scruff and a Pit Bull with whom she loved to wrestle.

But our last day at the dog park was the day that I heard someone say, as we approached the dog park gate, “Hera’s here!” and someone else respond, “I was just about ready to leave anyway.”

More unhelpful training

When Hera was about 18 months, we went to an adult dog training class. This instructor told us to use a prong collar. We bought one but often we “forgot” to bring it to class. We walked her with it a couple of times but just couldn’t get ourselves comfortable with the tool even after we’d followed the instructor’s directions to put it around our own thighs and jerk so we’d know it didn’t hurt terribly much. Bulldogs have a very thick, muscular neck and a very high pain threshold. Still, we didn’t use the prong collar much or consistently.

When the class practiced loose leash walking by zigzagging around the room, Hera would lunge at the other dogs. Hera was the only dog who didn’t pass the Canine Good Citizen (CGC) test in the class. She was given a diploma, but again, we knew it wasn’t “earned.”

During this time, Hera began exhibiting a new frightening behavior: jumping on anyone holding a live thing, such as a baby, another dog, or a cat. She would jump with a glazed look in her eyes, pupils dilated, seemingly obsessed. She didn’t bite or grab, but she would keep jumping until one of us could tackle her and manhandle her away.

This behavior made it more and more difficult to take Hera anywhere “safe” to let her off-leash. One spring morning, on a weekday about 6 a.m., when I thought it would be safe to take Hera to the beach for an off-leash romp, Hera spotted a man walking carrying an infant. I caught up with her as she was making her second or third jump up the man’s leg, and I body-tackled her. She squirmed away. Terrified, I grabbed her again and managed to instruct the understandably upset man to, “Please go away!” He asked what was the matter with my dog. I wished I knew!

So when Hera was about three years old, we brought in a dog behaviorist who met with us in our own home to see Hera’s environment and behavior. We were introduced to the concept of “nothing in life is free” (NILIF), where the dog has to perform some sort of behavior, on cue, before he “earns” any sort of reward – attention, food, a toy, affection, going outside, jumping up on the couch, etc. And we were told to repeatedly practice a very good “sit” and “down” so she would sit on command instead of jumping or lunging.

But the trainer also asked us why we didn’t put this dog down and get the dog we had intended: a malleable, obedient dog who would walk quietly on leash and sit beside me at cafes. We were frightened by the implication that her behavior was so bad the behaviorist was indirectly suggesting she be killed.

Even so, the consultation was helpful. NILIF gave us a good tool, and Hera’s sit became better, although it never was “strong” enough to interfere with her jumping or lunging. When she did a “down” at all, it was never for more than two seconds.

Concerned that all the pulling that she did on leash could damage Hera’s small Bulldog trachea, we changed to a harness. This eliminated pressure on her throat but also gave her even greater pulling leverage.

Life-changing events

When Hera was four, life changed for all of us. I moved to Washington, DC, for a four-month work assignment. I took Hera with me, since I would have ample time to spend with her after work. I vowed to spend the four months with a dog trainer who didn’t use physical force and who would work with us individually to make our walks less fraught with peril. Literally, that was my goal. I still have it written down on the form I completed for the instructor, Penelope Brown, of Phi Beta K-9 in DC.

Brown introduced me to the clicker and positive training, and I think of her as our turning point, our savior, who changed our lives. I tried to argue her out of the clicker, saying, “But I already have the leash in one hand, treats and poop bags in my pocket, a water bottle for the dog, and maybe, just maybe, I’d like to carry a coffee mug for me!” She was patient, knowledgeable, humorous, and persistent. I learned to use a clicker, stopped trying to carry a coffee mug, and learned to consider all of our walks as training opportunities.

Under Brown’s tutelage, Hera and I had a great four months! Not only did our walks become “less fraught with peril,” Hera finally learned to walk past other dogs without lunging, as long as I worked with her and we had a space of about 12 feet between them.

When we started, Hera’s “launch point” was two blocks away from another dog, with the dog on the opposite side of the street and walking away from us. I learned to read her body language and to scan our environment. Hera would see a dog and I’d “click” before she launched and shove a handful of treats in her face, as both classical conditioning to change her underlying emotional response to the sight and presence of other dogs, and, increasingly, as a reward for not launching herself toward the other dog.

I also learned to position treats in such a way so as to break her gaze and lure her away from the other dog. If she launched before I could do that, I learned to turn us away anyway and use that same handful of treats for classical conditioning.

We progressed. After about six weeks, Hera’s launch point had changed from two blocks to one. At this point, I added operant conditioning in that second block distance. When she looked at the other dog but did not display any aggression, I clicked and gave her a treat. In time, she learned to look at the dog and then turn to look at me on her own.

After about another month, if the dog was on the other side of the street, it could be coming toward us and pass (on the other side of the street) without a noticeable reaction from Hera. After another two or three weeks, the dog could be on the same side of the street walking in front of us/away from us, or behind us/not catching up, at a distance of about half a block. If I kept clicking and giving her treats at a rapid rate, she didn’t launch.

I continued to build on her progress, by spacing out the clicks, allowing her to look longer, one moment at a time, at the other dog. I became far more adept at reading her body language, and saw that now she would see another dog and “freeze,” not instantly launch. I observed that if the freeze lasted more than about two or three seconds, there was a higher likelihood that she would launch. If she broke the freeze before that, she was likely to initiate play if the dog was close or simply keep moving if the dog was farther off. So I would click and treat (if the other dog was far enough away for me to safely introduce food into the scene) after a two-second freeze. Hera would turn to me for the treat and that broke the freeze. Then she could look back at the dog and we’d repeat.

Sometimes I’d click and treat as I walked us away. I tried to judge the amount of tension Hera could tolerate before going “mindless.” The more we worked with positive techniques, the more self-control Hera gained.

More positive help

Hera and I returned home after my four-month assignment with a whole new bag of tricks to teach my husband! It was clear at this point I had become Hera’s primary trainer.

I looked for and found another wonderful positive trainer, this one near Boston. Emma Parsons, of The Creative Canine, in North Chelms-ford, Massachusetts, had personal experience with a dog-aggressive dog. She brought us further along our path and served as a living role model, proof positive that at least one woman and one dog had come out the other side of this nightmare. Parsons’ dog had been in competitions, could walk through a show area full of dogs, and lived at home with other dogs. I was heartened.

Parsons put us together with a local dog training club that kindly let us walk around on the edges of their classes. Hera and I could practice being calm in an environment full of dogs – an inside environment, very different and actually much harder for Hera than outdoors. Parsons was very patient and creative in teaching us what we needed to learn.

Sometimes it helps to see how someone else does something to make the words of instruction “real.” I had thought I was giving Hera lots of treats as we walked through dog-filled sections of the room but still she would frequently lunge at the other dogs. Then our trainer showed me, using her own dog, what she meant by giving treats “frequently” – at least five times the rate I was using! That was a major breakthrough in my learning and in Hera’s behavior.

I also learned that Hera was more stressed by a dog coming right at us than by a dog coming toward us at an angle. So, if a dog was coming right at us, we’d veer off and angle our direction.

I learned to walk while giving a lot of information to Hera: frequent clicks for calm behavior with lots and lots of really great treats, treats shoveled into Hera’s mouth as she took non-lunging step after non-lunging step. I was lucky. Some reactive dogs become so stressed that they won’t take even high-value treats, but Hera almost always took them.

My goal expanded from being able to walk my dog on city streets past other dogs, to being able to walk with her safely on a beach, where loose dogs could approach us without Hera exhibiting aggressive behavior. Eventually, we actually got there.

Advanced education: Dealing with loose dogs

First, Hera began to have more dog friends, walking companions. She’s always had at least a couple, so we had that to build from. Each dog was introduced to our social circle slowly and carefully, with me orchestrating the meetings until the dogs were at ease, usually for three or four meetings. I let them see each other at a distance, with lots of clicks and treats for Hera, zigzag walking around, progressing to some parallel walking, sometimes on opposite sides of the street, sometimes with the other dog on the same side and ahead of us.

Gradually I would close the distance for brief periods, extend the periods, close a bit more but for shorter periods, then gradually lengthen those periods.

Vivid in my memory is the day Hera was startled by the sudden appearance of a dog coming out of a door just yards in front of us. She froze, stared, and turned to look at me on her own! She had made the choice to look away in a highly charged situation! Treats flowed into her mouth for that, a jackpot like no other jackpot!

After that, I’d keep Hera’s attention ping-ponging between other dogs and me by clicking/treats for her voluntary head turn or clicking/treats to break the stare if I felt it was going on too long. When I misjudged and waited too long, she would launch. But “too long” varied and generally was getting to be a longer and longer time.

I learned to take things in smaller steps than I’d ever considered. When I could control the situation, I kept these sessions short (two to five minutes). When I couldn’t (dog off leash with no handler), they lasted as long as they lasted.

When Hera did play with another dog, while she was playing, I frequently repeated “Friend, Hera, it’s a friend!” I used a particular tone of voice and rhythm saying this phrase. For several months, I used it only when she was relaxed and playing with another dog.

Later, on the beach, if a loose dog came toward us, I would click and treat while it was at a safe enough distance to introduce food. When the other dog moved closer, I would start my “Friend, Hera, it’s a friend!” cue. I watched Hera and the other dog and if needed, I would step between them to break any intensity Hera might display. As the distance closed, I kept Hera’s attention ping-ponging between the dog and me, as described above. The dogs often got to meet but I orchestrated the lead-up and the actual meeting. I ended the meeting if I saw too much tension.

If the other dog was loose and seemed threatening, simply rude, or determined to come greet Hera when I could see Hera did not want this, I would sometimes toss some treats at the feet of the approaching dog to distract him. If he took those, my next toss would be over his head or to his side so he would turn for them. That made it much easier for Hera to turn away, too. Sometimes I looked at the other dog and said “SIT!” Amazingly, this sometimes worked, too.

Yet sometimes nothing would work, and Hera was sending clear signals she did not want to meet the oncoming dog or that she would behave aggressively. Then I would cue her to a U-turn (a technique advocated by Patricia McConnell in her book, Feisty Fido), chant my “Friend!” cue, and click and treat when possible. Often those things would do the trick and we would either avoid the meeting or the meeting would be brief and uneventful. Yet even now, there are occasions when Hera will lunge. She has come a very long way, but she is not, nor will she ever be (in my opinion), a “normal” dog.

About this same time, I saw the debut of the SENSE-ation Harness (see “Making Headway,” WDJ February 2005). I purchased one to replace her old-style walking harness. The leash clasps in front at the dog’s chest and this gives great control to the handler. This was another tool that really helped us.

By the time Hera was 6½, she could pass another dog on the sidewalk if I managed the situation. She no longer needed a 12-foot buffer zone; two feet would do. At that time, it was usually my preference to cross the street to avoid the stress it put on me and on Hera.

Pulled into a new career

If it sounds like I was immersed in dog training almost all the time, it’s because I was! The more I researched positive, effective dog training methods, the more interested I became in the field. I was excited when I learned about the Association of Pet Dog Trainers (APDT) and attended one of its annual educational conferences. I had gone to absorb information about positive training, but it turned out to be a significant step in my new career path!

As Hera and I learned and changed, I realized that I had a new passion, a new career. I wanted to be a pet dog trainer, and help others avoid going as far down the dismal road that we had traveled, and help them come back if they were already on it.

I found a positive trainer in my area, explained I was preparing myself to become a positive pet dog trainer, and asked to volunteer with her. I also added a part-time job to my day job, working at a doggie day care. There, I learned more about how “nice” dogs interact freely with each other and how to read their body language, intervene effectively, redirect behaviors and attention, and practice what I’d learned from Norwegian dog trainer Turid Rugaas’ tapes and booklet.

I joined Clicker Solutions, a Web site and e-mail list “dedicated to helping pet owners improve the relationship with their pets by teaching training and management techniques which are understandable and reinforcing to both human and animal.” On this and other lists that discussed positive training for aggressive dogs, I coined “Hera-the-WonderDog!” as Hera’s identifier, because I saw she truly was a wonder dog!

When Hera was seven years old, with the help of other wonderful positive trainers who also let me assist them, plus an abundance of workshops, seminars, conferences, journals, e-lists, books, etc., I started “My Dog, LLC,” my pet dog training business. Of course, for me, it had all started with my dog.

Presently present

Today, Hera is nine years old. She will never be the dog who sits ignored at my feet at a cafe, nor the dog ambling beside me on a walk, while I ignore her and chat with my friend. I am always watchful and managing and training. But now, sometimes, I take my plastic coffee mug on our neighborhood walks. (Yes, there have been a few times when I’ve dropped the coffee to manage a surprise situation!)

Outside, Hera is my focus. I glance around at trees, houses, and storefronts, but I also scan for other dogs, roller bladers, skateboarders, cats, squirrels, Canada geese, infants in arms/small dogs being carried, big trucks, or fast moving vehicles of any sort moving right at us. I watch her body language to know when she is stressed. She teaches me what concerns her, and I do my best to give her enough information to get through it or I manage the environment to reduce or remove the stressor.

The clicker is my main communicator. And treats. Even today, when we go to local parks, the waiting room at her vet’s, and pet supply stores -places frequented by people with their dogs – we train with clicker and treats. When we sit at a table outside my favorite coffee shop, I have my coffee, clicker, and several different treats at my fingertips. We enjoy the weather, watch the world go by, and train. Always, we train.

Much of the time now, Hera seems interested in meeting the other dog, so I orchestrate by ping-ponging her attention, zigzagging and blocking approaches, happy talk, cuing “friend!” and using clicks and treats as much as possible, as well as keeping first sniffs brief. I turn her away and come back, and end the meeting while all is still going well. Often, now, Hera ends the meeting on her own!

If I am in doubt as to Hera’s stress level, her ability to handle the situation, I get us out of the situation. I say, “Let’s GO!” and we turn and trot away. Click and treat for both of us! We don’t need to do that very often any more, but knowing it is there, our safety net, helps me feel more comfortable. And we practice a quick U-turn. I’ve taught it to her on the cue “Wow!” because I simply can’t sound panicked and stressed when I say “Wow!”

Hera now has doggie friends. I value each of them. We meet for walks. We make new friends carefully, with disclosure of Hera’s reactivity and how we manage our greeting rituals. Each new friend, each acquaintance she tolerates, is a major delight! Some dogs (more and more all the time), she simply meets and greets. I can’t say she does it “normally” because I believe that under the surface, the reactivity is still there. But now she has a much thicker surface, a greater buffer of resilience before her reactivity is triggered.

Take nothing for granted

Obviously, this training approach has become our lifestyle. With a reactive dog, you take nothing for granted. Building a solid base and watching the dog to evaluate and reevaluate when and how fast to progress is critical.

In November 2003, she received – and deserved! – her Canine Good Citizen certification, and in early 2004 she participated in a “clicker tricks” class and did very well.

I love this dog. I wish I could go back and change those first four years, but I can’t.

What I can do is use positive techniques with her for the rest of her life. I can and will keep learning to better help her at every stage.

I encourage her to use her lovely, bright, eager mind. We play games, she does backyard agility, and she does tricks. She visits folks in a local nursing home weekly. She holds a lovely long “sit” and has a pretty “down.” She greets people with a sit and a “high five” or a “wave,” as cued, and shakes paw when asked, all learned with the clicker and positive reinforcement – all learned with glee, not pain, not stress, not resistance.

Hera now makes up games and initiates play. She snuggles with me, lets me clean and care for her face wrinkles, and accepts brushing. She’s truly my wonderful, wonderful, wonder dog.

Editor’s note: Caryl-Rose’s husband Billy was diagnosed with cancer in mid-2004 and he passed away that September. With his support of and involvement with Hera’s behavior rehabilition, Billy was an important contributor to Hera’s success. She returns the favor by loving and supporting Caryl-Rose in Billy’s absence.

Caryl-Rose Pofcher is owner of My Dog, LLC, in Amherst, Massachusetts. This is her first contribution to WDJ.