Download the Full March 2007 Issue PDF

Listmania

Hurray! Another annual food review is complete (and Ive got another pile of food to take down to my local animal shelter!). Im especially glad to be done with fact-checking the list of our top wet foods, because companies relocate, change their phone numbers, revamp their product lines, and fiddle with ingredients lists. The task is increasingly tedious, especially after 10 years of adding products to the list.

288

Speaking of which, it seems like more products than usual got added this year, and not necessarily because they were new. I tried to check with the manufacturer of each of our favorite dry dog foods, to make sure I hadnt overlooked their fine wet products (in several cases, I had).

In other, rare cases, I added a product from a company that already had one or more foods on our list. Youll have to take my word for it, but I hate to add more than one product from any manufacturer to our list; Id prefer to introduce you to an increasing number of pet food makers, especially companies who offer superior products in underserved areas. However, I broke my own unofficial rule in the case of some new and especially compelling products that emerged from a couple of companies that are already on our list.

Until last year, I had never removed a product from our top food lists; though manufacturers do change their formulas from time to time, none of the foods on our lists have changed in a way that would prevent them from meeting our selection criteria. Last year, however, I was surprised by a formula change in a product I had previously approved: the inclusion of animal plasma in a canned food made by Wysong. I took the product off the list without comment, and have been compiling information about the use of animal plasma in food products ever since.

The blood of cows and pigs is collected in some slaughterhouses and processed into a dry powder. Its used extensively in the diets of young pigs and calves. Its also sometimes used as a palatant in a final coating on extruded dog foods and as a protein-rich thickener in canned pet foods. Studies suggest that it is highly digestible; in fact, its inclusion in a canine diet greatly improves the digestion of the diets fiber meaning you can include more (low cost) fiber in a food and the dog will still be able to digest it. An additional selling point is that it tends to make the dogs stool smaller and harder.

Im sure that feeding cow brains to cows once seemed like a really good idea, too.

In case that comment doesnt seem fair, let me be clear: I dont have a single study to cite to justify my gut instinct to cull products that contain animal plasma from our top foods lists. It feels just as wrong to me as feeding beef products to cows. While some nutritionists will utilize any ingredient with perceived benefits, I side with the health and nutrition experts who encourage us to eat (and to feed our dogs) a varied diet of real foods. I mean, with so many healthful, natural, and minimally processed ingredients from which to build a diet, why even go there?

Whole Dog Journal’s 2007 Canned Dog Food Review

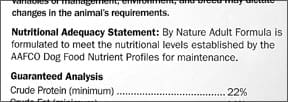

How should you choose a canned food for your dog? To start, by looking past its advertising in dog magazines or its front label. We suggest you focus on its ingredient panel, its guaranteed analysis (GA), and finally, on its performance in feeding trials with your dog.

Here is why you have to work a little to find the right food for your dog.

Good ideas get replicated quickly in any competitive market. Products that demonstrate any increased sales performance or popularity are copied and aggressively promoted against the originals.

288

The pet food market is no different. As products that contain top-quality muscle meats, whole grains, and healthy vegetables become increasingly popular, more and more of these foods are offered. That’s great news for our dogs.

The bad news is that along with the increase in genuinely superior products comes an increase in superficially (or artificially) superior products foods that really aren’t all that good. That’s where the marketing department comes in! With glossy studio shots of succulent meats, earthy grains, and fresh, ripe vegetables, professional portraits of flawlessly fit, clean dogs, and a sprinkling of ambiguous verbiage, any dog food can appear to compete with the healthiest products on the market. Especially if you add nominal amounts of the latest “fad” ingredients, blueberries, say, or pomegranate juice, to the product formula. We beg you to put the advertising aside and consider the ingredients themselves.

What’s in the can?

Wet dog foods offer your dog a few advantages over kibble. At levels of 70 to 80 percent moisture, canned dog foods are beneficial to dogs with kidney ailments. All that moisture can help a dog who is on a diet feel full faster (although you should look for low-fat products, as most canned foods are higher in fat than their kibbled counterparts). Canned foods retain their nutrient value longer two years or more, although their contents may change color and texture with time. Dry dog foods, in contrast, experience significant vitamin loss within a year of manufacture (longer for artificially preserved foods, less time for naturally preserved products).

Most significantly, though, the majority of wet foods contain far more animal protein (the dog’s evolutionary staple) than dry foods. Animal proteins are higher in biological value to the dog; they contain more of the amino acids that dogs can’t manufacture themselves, but must consume in their diets (essential amino acids). Though their digestive systems are beautifully able to extract at least some nutrients from just about anything edible, dogs benefit most from meat, especially when it is served up with proportionate amounts of the fat, connective tissue, organs, and even bone that originally came with the meat!

(While we’re on this topic, I’ve been asked several times to identify little pieces of white, bone-like material that a dog owner found in his or her dog’s canned food. If the food contains chicken, the answer is easy; those little flecks are tiny edible pieces of bone. Chicken “frames” (the carcass after the feathers, organs, head, neck, legs, and the breast meat have been mechanically removed) constitutes a hefty percentage of the “chicken” used in pet food. Some muscle meat is attached to the frame, as is a lot of connective tissue. “Chicken” may also contain chicken skin. The legal definition of chicken is “the clean combination of flesh and skin with or without accompanying bone.” Fish “frames” are also common in pet food.)

In addition to being more digestible, wet foods that contain mostly meat are also more palatable to dogs. (Conversely, the more grains and non-meat ingredients are present in a wet food, the lower its palatability.) Best of all, the meat used in canned pet food is usually fresh or frozen; generally, the meats in canned foods are of higher quality that the meats used in dry food.

What’s all this other stuff?

In some wet foods, you may see little more on the ingredients list besides an animal protein source, water or broth (required to help with the physical processing of the material), and the vitamin/mineral sources. The latter are added in amounts that ensure adequate levels of those nutrients even after certain percentages of the vitamins are destroyed by the heat of the sterilization process required for wet foods in cans, trays, and pouches. Often a carb source is used in a nominal way as a thickener/binder. Various types of “gum” (such as guar gum, from the seed of the guar plant, and carrageenan gum, from seaweed) are also common thickeners.

What about all these grains and vegetables and so forth?

Ideally, these extra ingredients have been included for some specific nutritional purpose and benefit. The manufacturer includes a certain amount of blueberries, for example, because of studies that indicate dogs may benefit from the addition of X amount of the unique antioxidants found in the berries.

On the opposite end of the spectrum of rationales for the addition of ingredients is something called “least-cost formulation.” This is just what it sounds like. It’s the method used for determining how a food that contains nutrients at the levels required to sustain dogs can be made as inexpensively as possible. Look at the ingredients labels of the products made by the largest pet food makers in the world and you’ll see what this entails.

Somewhere in the middle of this continuum is the marketing we mentioned in the beginning of this article. If a study comes out suggesting that rose petals can make people live longer, and one pet food that contains rose petals starts selling well, you can bet that rose petals will soon find their way into a number of pet foods.

The use of even the most nutritious “human” food ingredients can be overdone. While it sounds very appetizing (to us!) when a food contains a long list of whole ingredients, including many foods you might find in your refrigerator and cupboards, the more there is of all that in the can, the less room there is for meat. And with canned dog foods, meat should be mainly what it’s about (this goes double for canned cat foods, incidentally).

And you have to keep in mind that dogs have no biological requirement for any carbohydrates; they can thrive without them. Carbohydrate sources are often used in dog food as fillers (and effective binders), although manufacturers will tell you that they have included their carb sources for some nutrient or another, or because they are an important fiber source, helping slow the dog’s digestion and make it more efficient. The latter claims may be true, but the fact remains that all carb sources are less expensive than animal-based proteins and are not required by the dog. We strongly prefer wet dog foods that contain small amounts of grain or no grain at all.

That said, you’ll see that many of the foods that appear on our “top wet foods” list contain grains, veggies, and many other non-necessary ingredients. Here’s why.

What we have attempted to do is to highlight a variety of products that meet our selection criteria for wet dog foods (outlined below). Some of the foods on our lists contain much more animal protein than others; some are extremely high in fat, and other are at the low end of the scale. Some are quite expensive; others may compete in price with bargain grocery-store brands. Some may be found only in specialty pet supply stores in a few states, or by direct order from the manufacturer; some are ubiquitous, and can be purchased in any chain pet supply superstore. What they all have in common is that they are better than most wet dog foods!

Whole Dog Journal’s selection criteria

Here’s how we determine whether a wet food is truly “premium.”

- We eliminate foods containing artificial colors, flavors, or added preservatives.

- We reject foods containing fat or protein not identified by species. “Animal fat” and “meat proteins” are euphemisms for low-quality, low-priced mixed ingredients of uncertain origin.

- We reject any food containing meat by-products or poultry by-products. There is a wide variation in the quality and type of by-products that are available to pet food producers. And there is no way for the average dog owner (or anyone else) to find out, beyond a shadow of a doubt, whether the by-products used are carefully handled, chilled, and used fresh within a day or two of slaughter (as some companies have told us), or the cheapest, lowest-quality material found on the market. There is some, but much less variation in the quality of whole-meat products; they are too expensive to be handled carelessly.

- We eliminate any food containing sugar or other sweetener. Again, a food containing quality meats shouldn’t need additional palatants to entice dogs.

- We look for foods with whole meat, fish, or poultry as the first ingredient (and perhaps the second and third ingredients, too!) on the label. (Just as with food for humans, ingredients are listed on the label by the total weight they contribute to the product.) If water is the first ingredient on a canned food label, that product had better have something else really special going for it.

- If grains or vegetables are used, we look for the use of whole grains and vegetables, rather than a series of reconstituted parts, i.e., “rice”, rather than “rice flour, rice bran, brewer’s rice,” etc.

Go forth and compare

On the following pages, we’ve listed a number of canned dog foods that meet our selection criteria. It’s vitally important that you understand the following points regarding these foods:

- The foods on our list are not the only good foods on the market. Any food that you find that meets our selection criteria, outlined above, is just as good as any of the foods on our list.

- If the variety we describe doesn’t suit your dog’s needs, check its maker’s website or call their toll-free phone number to get information about the other varieties in the same line.

- Quality comes with a price. These foods may be expensive and can be difficult to find, depending on your location. Contact the maker and ask about purchasing options. If the customer service representatives are less than helpful, move on to another product. As you’ll see from our list on the following pages, there are plenty from which to choose.

- We have presented the foods on our list alphabetically. We do not “rank order” foods. We don’t attempt to identify which ones are “best”, because what’s “best” for every dog is different.

- If your dog does not thrive on the food, with a glossy coat, itch-free skin, bright eyes, clear ears, and a happy, alert demeanor, it doesn’t matter whether we like it or not. Take notes, and date them! Sometimes it takes several years of detective work to find products that really suit your dog.

Using the selection criteria we have outlined above, go analyze the food you are currently feeding your dog. If it doesn’t measure up, we encourage you to choose a new food based on quality, as well as what works best for you and your dog in terms of types of ingredients, levels of protein and fat, and local availability and price.

Athletic Dogs and Acupressure Techniques

When spring is in the air, every dog knows it. Spring is the season when dogs want to run, play, and stretch their bodies, when their eyes brighten, and their natural zest for life flows through their veins. Spring is a time of action.

There are so many canine performance sports today that require peak levels of running, twisting, turning, jumping, and pivoting. Anyone watching a canine agility trial or flyball competition can see the adrenaline pumping through every ounce of the dog’s being. Adrenaline can override the senses and the animal can unknowingly hurt himself badly, especially early in the season.

The risk of injury is very high when a dog is not properly conditioned. Also, dogs need to be given the opportunity to warm up before engaging in the burst of excitement and energy they experience at the moment they are released for coursing, a herding test, or on a sledding trail.

Physical conditioning takes time and different parts of the body condition at different rates. Muscles are first to build. Cardiovascular conditioning occurs next. This is followed by the strengthening of tendons, and then ligaments, which hold the joints securely.

All conditioning regimes need to be designed for each specific dog and his particular sport. Training programs for a dog will depend on his age, breed, weight, and current general fitness level.

Canine Exercise

Physiologists usually recommend that a dog begin conditioning by successive short runs in a straight line; that is, run 50 to 100 yards, stop, walk, run another 50 to 100 yards, and so on. By traveling in a straight line on a surface with good traction, the dog’s muscles and tendons are allowed to strengthen while not being overly stressed.

The next step in conditioning is to progress toward running on uneven terrain with incrementally increased amounts of turning and pivoting to build well-rounded muscles and strong, flexible tendons and ligaments.

Exercise experts advise dog owners to make sure their dogs warm up before (and cool down after) strenuous exercise. Remember to make water available for the dog before and after activity.

Watch for fatigue and any indication of pain. A dog will naturally shift his body weight or alter his gait to compensate for tired muscles or pain, thus compromising other parts of his body. Injuries tend to occur when the body is off-balance, even slightly. Also, veterinary sports medicine practitioners report that the most common canine orthopedic injuries are repetitive stress injuries caused when the dog is tired but naturally driven to continue.

Enhance Conditioning with Acupressure

The ancient healing art of acupressure offers a method of enhancing the conditioning process. Acupressure, which is based on Traditional Chinese Medicine, is known to:

-

Build flexibility of tendons and ligaments

-

Decrease inflammation of soft tissues and joints

-

Strengthen and warm muscles by supplying necessary nutrients

-

Relieve muscle spasms by establishing a smooth flow of energy and blood

-

Remove toxins from an injured area while replenishing with healthy cells, and

-

Reduce the painful build-up of lactic acid in the muscles by increasing blood circulation.

Acupressure Session

On the dog’s body there are specific acupressure points, or little energetic pools, where we can access and thus influence the flow of energy, in this case, to optimize the dog’s conditioning program. The following acupressure points, also called “acupoints,” can be used while building toward peak performance.

-

Bladder 17 (also known as “Diaphragm Transporting.”) Bl 17 is a powerful acupoint that enhances the flow of blood throughout the body. Cardiovascular health is the key to all the biomechanical functions of the body. Good blood and energy circulation ensures that all the tissues receive nourishment, so that healthy cells can form while lactic acid and toxic substances are removed. It is the continuous flow of replenishment and removal that makes for the strengthening and building of muscles, tendons, and ligaments.

-

Gall Bladder 34 (“Yang Hill Spring.”) GB 34 is used facilitate the flexibility of tendons and ligaments. Tendons and ligaments are like the new, young branches on a tree; when the wind blows, they must be flexible and bend, or they will snap and break. Maximizing the flexibility and strength of ligaments helps increase the flexibility and weight-bearing capacity of the joints.

-

Spleen 6 (“Three Yin Meeting.”) SP 6 is often used to nourish the muscles and other soft tissues of the forelimbs and especially the hindquarters. Good muscle tone is dependent on nutrient-rich blood. SP 6 is known for its ability to enhance the circulation and nourishment of the blood.

-

Stomach 36 (“Leg Three Mile.”) As the “master point” for the gastrointestinal system, ST 36 is very important in converting food substances into refined, bioabsorbable nutrients to be circulated in the blood. ST 36 is known for its ability to contribute to a dog’s overall physical endurance because it promotes energy throughout the body.

Between receiving a spring maintenance acupressure session every five to six days and careful physical conditioning, the canine athlete will have a good time getting back into action this spring.

Acupoint Technique

Settle down in a quiet, comfortable space with your dog for an acupressure session, always keeping two hands on his body. Rest the soft tip of your thumb on an acupoint and exert about one pound of pressure (less for smaller dogs). Place your other hand comfortably on another portion of the dog’s body. On smaller dogs it may be more comfortable to use your index finger with your middle finger on top of it for the point work instead of your thumb.

Keep your thumb, or index and middle finger, on the acupoint for at least the count of 30. If your dog shows any signs of distress or pain while holding the point, stop and try it again some other time.

All of the acupoints are located on both sides of the dog’s body. Once you complete the series on one side, ask the dog to turn or roll over and work on the same acupoints on the other side.

You will know you are doing a good job when your dog indicates he is experiencing energy moving more smoothly through his body. Dogs express the movement and harmonious flow of energy by yawning, stretching, passing air, rolling over, licking in general or licking your hand on the point, or sometimes just breathing more deeply and falling asleep.

Amy Snow and Nancy Zidonis are the authors of The Well-Connected Dog: A Guide to Canine Acupressure, Acu-Cat: A Guide to Feline Acupressure, and Equine Acupressure: A Working Manual. They founded Tallgrass Animal Acupressure Institute, which offers a practitioner certificate program and training programs worldwide, plus books, meridian charts, and videos.

Good Dog Walking

Dog owners often bemoan the paucity of public places in our society where their dogs are welcome. We band together and lobby mightily to secure small spaces in our communities for dog parks. We struggle to preserve dog-use rights in public common areas. And while I share the dismay over the shrinking access for our canine companions, I know that to a large degree we’ve brought it on ourselves by our collective carelessness about proper public and leash-walking etiquette.

Picture yourself strolling down Main Street, your faithful companion stepping smartly alongside you on a loose leash. This is the image most pet owners have in mind when they adopt a warm fuzzy puppy, or offer to give a shelter or rescue dog a second chance for a lifelong loving home. In reality, however, walking the dog is more often a chaotic scene of canine dragging human down the sidewalk at the end of the leash, rudely approaching other dogs, jumping on passers-by, and snapping at the heels of joggers. Where did things go wrong?

What is a walk?

Much of the problem with ill-behaved dogs on leashes stems from the fact that many dog owners have a major misconception about exercise. A walk is a great social outing for you and your dog. It’s a good bonding experience, an opportunity for you to stretch your legs, and the perfect time to work on training generalizing your dog’s learned behaviors to new environments with new distractions.

What a walk is not, however, is adequate exercise for your dog. Unless you are a marathon runner, or your dog is elderly or has some physical problem, a walk around the block is simply an exercise hors d’oeurve for your furry pal.

Think about it. If you took your four-legged friend for a hike in the hills, off-leash (assuming it’s legal and he’d stay with you and has a decent recall), he’d run circles around you. And at the end of the hike, as you dragged yourself back to the car on tired legs, he’d still happily be making loops around you, begging for another trip around the trails. Face it. For most dogs, a polite walk around the block is rather slow and boring and if the energy level is high, some dogs will resort to lunging, barking, and worse, to spice up the experience.

Train, train, train

Another piece of the problem is simply a failure on the part of many owners to teach their dogs to walk politely on leash. Despite an emphasis on this important behavior in many good manners classes, some humans just aren’t motivated to practice reinforcing polite walking enough to make it a habit for them or their dogs. This is especially true in suburban and rural areas, where dogs have yards or farms to run in, as opposed to city-dwelling dogs whose only outlet for fresh-air exercise may be a walk on leash.

I personally find it very annoying to have a dog constantly yanking on my arm, so even though I live on 80 acres, I take the time to teach my dogs two different cues for walking: “Let’s walk,” which means “You can act like a dog occasionally stopping to sniff, pee, and explore as long as you don’t drag me,” and “Heel,” which means “Walk at my side, refrain from sniffing, sit when I stop.”

Teaching your dog to walk politely on leash is more than just a convenience. When you can walk in public with your dog following your moves like a dance partner, he’s more likely to stay out of trouble.

Teaching “Let’s walk”

Remember that your dog’s leash is not a steering wheel or handle. It’s a safety belt, intended to prevent your dog from leaving. It’s not to be used to pull him around, nor should he drag you along behind him.

Whether you’re teaching “Heel,” or the less formal “Let’s walk!” the correct position for the part of the leash that stretches from you to the dog is slack, hanging down in a valley. Be sure when your dog is with you that you keep the leash slack. If you keep it tight, he’ll think tension in the leash is normal and correct.

For left-side walking, start with your dog sitting by your left side. I suggest holding leash and clicker in your left hand (same side as the dog) and having a good supply of treats in your right hand. For right-side walking, just switch all the equipment to opposite hands. Make sure there’s enough slack in the leash so it stays loose when your dog is in the reinforcement zone you’ve identified for polite walking. You can also use a waist-belt or otherwise attach your dog’s leash to your person, as long as he’s not big enough to knock you down and drag you.

Use your “Let’s walk!” cue in a cheerful tone of voice and start walking forward. The instant your dog begins to move forward with you, use an audible marker, such as the click! of a clicker or the word, “Yes!” and give your dog a treat. (The click or “Yes!” is used to “mark” the behavior you want the dog to repeat, and the treat reinforces that behavior.)

At first, click! and treat very rapidly, with almost every step. Remember, you’re not teaching “Heel!” right now. Click! and treat as long as there’s no tension in the leash, although I do suggest you choose one side and reinforce on that side only, to keep him from crossing back and forth in front of you. When your dog realizes it’s worthwhile to stay within a designated radius of his generous, treat-dispensing machine (you!), you can gradually reduce the rate of reinforcement.

Careful! If you reduce the rate too quickly or too predictably, you’ll lose the behavior. As you gradually reduce the rate of reinforcement, be sure to click! and treat randomly so your dog never knows for sure when the next treat is coming. If he knows you’re going to reinforce every tenth step, he can get careless for nine steps, and zero back in on you on the tenth. This phenomenon is called an interval scallop or a post-reinforcement pause. We humans are creatures of habit, and easily fall into predictable patterns. And our dogs are masters at identifying patterns.

The manner in which you hold and deliver your treats is critical to success with polite walking. When you walk, have the treats in your hand but hidden behind your hip on the side opposite your dog. If you hold them in your hand on the same side where your dog can see or smell them, it will be harder to “fade” (slowly eliminate) the presence of the treats later on. If you hold them in front of you, your dog will keep stepping in front of you to watch your hand (treats), and you’ll keep stepping on him.

To deliver treats, wait for a second after the click! as you keep walking, then bring your hand across the front of your body and feed the treat. Quickly move your hand behind your hip as soon as you’ve delivered the treat. Feeding the treat in the location where you want your dog to be reinforces that position. If you’re teaching him to walk on the left, feed on the left side. If you’re teaching him to walk on the right, feed on the right. If you feed the treat in front of you, you’ll reinforce that position, and you’ll be stepping on him again.

Remember to click!, then give him a treat after a brief pause. If you begin to move your treat hand toward him before the click!, he’s just thinking about food rather than what he did to make you click the clicker.

For the same reason, you want to lure (hold the treat in the position where you’d like him to be) as little as possible during leash walking. Luring will keep him in position, but it interferes with his ability to think. Your goal is to get him to realize that walking in the desired reinforcement zone makes you click! the clicker, and earns him a reward.

Teaching the “Heel”

If your goal is a show-ring heel, continue to shape for a more precise position as previously described, until your dog will walk reliably with his shoulder in line with your leg. Then change your cue from “Let’s walk!” to “Heel!” so your dog can distinguish between “now we’re going for a relaxed stroll,” and “now we’re working for that perfect 200-point score.”

Of course, it sounds good in theory, but can’t possibly be that simple. There will be times when your dog forges ahead of you and tightens the leash, or stops to sniff something of interest as you walk past him. There are positive solutions for those challenges as well.

When you have to pass a very tempting distraction, go ahead and lure, briefly, to get your dog past it. Put a tasty treat at the end of his nose; the more tempting the distraction, the higher value the treat and walk him past. As his polite walking behavior improves, your need for luring should diminish.

About face

Direction changes can be useful in teaching polite leash walking. When your dog starts to move out in front of you, before he gets to the end of his leash turn around and walk in the opposite direction.

Do this gently; you don’t want him to hit the end of the leash with a jerk if he doesn’t turn with you! As you turn, use your cheerful voice and a kissy noise to let him know you’ve changed direction. When he notices and turns to come with you, click! and offer a treat. He’s now behind you, and you’ll have lots of opportunities to click! and treat while he’s in the loose-leash zone as he catches up and walks with you.

Be a tree

There will be times when your dog pulls ahead of you on a tight leash. This is a great opportunity to play “Be a tree.” When the leash tightens, stop walking. Just stand still like a tree and wait. No cues or verbal corrections to your dog. Be sure to hug your leash arm to your side so he can’t pull you forward.

Eventually, he’ll wonder why his forward progress has stopped, and look back at you to see why you’re not coming. When he does, the leash will slacken. In that instant, click! and feed him a treat at your side. The click! marks the loose leash behavior; he’ll have to return to the reinforcement zone to get the treat. Then move forward again, using a higher rate of reinforcement if necessary, until he’s walking politely with you again.

Penalty yards

If “Be a tree” is not working, add “Penalty yards.” Your dog usually pulls to get somewhere or to get to something. If he won’t look back at you when you make like a tree, back up slowly with gentle pressure on the leash, no jerking, so he’s moving farther away from his goal. This is negative punishment; his pulling on leash behavior makes the good thing go farther away. When the leash slackens, click! and treat, or simply resume progress toward the good thing as his reward.

Go sniff!

Sniffing is a natural, normal dog behavior. If you never let your dog sniff, you’re thwarting this important hard-wired behavior. He may become frustrated and aroused if he’s constantly thwarted, so when you’re doing polite walking together, sometimes give him permission to sniff.

If he stops to sniff keep walking, putting gentle pressure on his leash to bring him with you, giving him a click! and treat as soon as he moves forward. When you know you’re approaching a good sniffing spot, however, you can give him permission by saying “Go sniff!” Give him enough leash to reach the spot without pulling, even running forward with him if necessary. You can also use “Go sniff” as a reinforcer for a stretch of nice leash walking!

Pat Miller, CPDT, is Whole Dog Journal’s Training Editor. Miller lives in Hagerstown, Maryland, site of her Peaceable Paws training center. She is also the author of The Power of Positive Dog Training and Positive Perspectives: Love Your Dog, Train Your Dog.

Home Treatments for Injured Dogs

DOG INJURY HOME TREATMENTS: OVERVIEW

1. If your dog hurt his leg, take him straight to the vet for any injury that might be serious.

2. Treat acute, inflamed injuries with cold. Treat chronic injuries with heat.

3. Keep your canine athlete in top shape with regular massage, chiropractic, acupuncture, acupressure, or other therapies.

4. Use supplements, improved diet and herbs to speed tissue repair and reduce inflammation around your dog’s injury.

Dogs At Risk for Pulling Muscles

A muscle strain in the dog’s leg, then a pulled ligament, a sprain, a bruise – pretty soon we’re talking about serious problems. Canine sports injuries are increasingly common, but there is much you can do to catch them early, treat them correctly, and reduce the risk of your dog getting badly hurt, needing surgery, or having to retire from competition.

Every dog is a candidate for injury, but those at special injury risk include:

– overweight dogs

– weekend athletes

– couch potatoes

– dogs with arthritis

– dogs engaged in search and rescue

– dogs who compete in flyball, agility, freestyle, disc dog (Frisbee), field work, dock diving, obedience, weight pulling, dog sledding, and other sports

Signs of Injury in Dogs

Dog injury signs aren’t always obvious. In fact, as Morgan Spector notes in Clicker Training for Obedience, dogs are very good at hiding injuries, a behavior that stems from an atavistic survival mechanism. As a result, we seldom realize that dogs are in pain until the damage is serious.

To identify canine injuries early, train yourself to be observant. Get in the habit of watching your dog stretch, turn, walk, run, and jump. Ask for help from visually oriented friends and trainers. When alignment is perfect and muscles are toned, a dog’s motions are balanced and graceful. Serious limps are obvious, such as if your dog sprained a wrist, but if you pay attention, you’ll notice more subtle symptoms, like tightness, tenderness, restricted movement, and even the slightest change of gait.

Range-of-motion exercises, such as using a treat or toy to lure your dog into a tight turn to the right or left or raising and lowering her head, can call attention to minor problems. Daily massage and gentle touch offer clues, too. Does your dog turn away when you stroke or press her hindquarters? Does any area feel unusually warm? Hard or stiff? Tender or swollen? Not the way it felt yesterday? Touch is one of the fastest ways to discover inflammation, muscle strains, and other discomforts.

When you notice changes, keep track of them in a calendar or notebook. If needed, an accurate history of symptoms and treatments will help veterinarians and other therapists understand your dog’s injury.

Obviously, any serious problem should be attended to at once. Whenever you’re in doubt, go straight to your veterinarian, rehabilitation clinic, veterinary chiropractor, canine massage therapist, or other specialist.

First Aid for Dogs with Pulled Muscles

The most important first-aid treatment for any injury is rest, and the simplest additional therapies are heat and cold. Which should you use when?

An acute injury is one that flares up quickly, within 24 to 48 hours of the incident that caused it. Acute injuries usually result from a sprain, fall, collision, or other impact, and they produce sharp sudden pain, tenderness, redness, swelling, skin that feels hot to the touch, and inflammation.

Cold is recommended for acute injuries because it reduces swelling and pain. Injured dogs instinctively seek puddles, ponds, streams, and winter snow banks in which to stand or lie.

A bag of frozen peas makes a convenient cold pack because it can be placed just about anywhere on the body, conforming to fit. Cold therapy products for pets, such as On-Ice bags and covers, are available from pet supply stores. Medical supply companies sell a variety of cold packs for sports injuries. The ones that contain a gel that stays malleable even when frozen are especially helpful for molding around a dog’s musculature.

Because cold restricts circulation and ice left in place for too long can cause complications, wrap any uncovered ice pack in a towel before applying it, remove the ice pack after 10 or 15 minutes, and wait at least two hours before reapplying. Never apply cold treatments just before exercise, workouts, training sessions, or competition.

Heat is recommended for chronic injuries, which are slow to develop, get better and worse, and cause dull pain or soreness. The usual causes of chronic injuries are overuse, arthritis, and acute injuries that were never properly treated. Heat therapy helps sore, stiff muscles, arthritic joints, and old injuries feel better because it stimulates circulation, helps release tight muscles, and alleviates spasms.

Heat is not recommended for acute injuries, areas of swelling or inflammation, or for use immediately after exercise.

To apply moist heat safely and effectively, place a damp towel in a hot clothes dryer or microwave for a minute or two. Be sure the towel feels hot but not uncomfortably so (test it on your inner wrist and let it cool if necessary), then fold it to fit the affected area. An extra towel on top helps retain warmth. Apply heat to the injury for 10 to 15 minutes, then wait another 15 minutes or longer before reapplying.

Electric heating pads are not usually recommended for canine use. Microwavable pet heating pads like the Snuggle Safe and the ThermoWave release safe, gentle heat for hours.

Bodywork for Muscle Injury Relief

Massage is one of the easiest techniques for handlers to learn, and most dogs enjoy being stroked, kneaded, stretched, and rubbed. (See “What to Think About When Petting Your Dog,” for petting techniques.) Massage, myotherapy (trigger point work), and other hands-on techniques not only treat injuries, they help prevent them by improving circulation, repairing damaged tissue, soothing the patient, and restoring range of motion. Canine massage therapists and canine myotherapists are health care professionals with special training in the treatment of sports injuries.

Chiropractic adjustments correct the alignment of joints and vertebrae in order to relieve pain, reduce muscle spasms, improve coordination, and enhance overall health. Veterinary chiropractors often specialize in sports injuries.

Acupuncture speeds healing by increasing circulation to affected areas, relieving pain, improving musculoskeletal problems such as arthritis, disc disorders, stiffness, or lameness, and balancing the body’s energy. Its close relative, acupressure (See “Athletic Dogs and Acupressure Techniques“), which involves holding acupuncture points rather than inserting needles, can be used for emergency first aid, rehabilitation, and injury-preventing conditioning.

Tellington TTouch (pronounced tee-touch) is beneficial to canine athletes because its circular touches actually change the way dogs process information. These simple motions can help your dog switch mental gears and focus on the present moment, release tension, and feel confident instead of fearful. The most widely known TTouches for dogs are the ear slide (holding the dog’s ear between thumb and bent forefinger, slide fingers from base to tip and repeat until the entire ear has been stroked) and ear circles (make small circles all over the ear). Ear TTouches have a calming effect in emergencies or whenever the dog is under stress, distracted, or in pain.

TTouch exercises like maze-walking (stepping over and around low obstacles) while wearing an elastic bandage body wrap help dogs understand where their hind ends are. This proprioceptic (neuro-muscular) awareness improves coordination and reduces injury risk. See “Calming TTouch for Noise-Phobic Dogs“, and “TTouch Practitioners Explain Canine ‘Body Wrapping,” for tips on using TTouch for your dog’s comfort.

With the help of books like Physical Therapy for the Canine Athlete by Suzanne Clothier and veterinary chiropractor Sue Ann Lesser, DVM, you can guide your dog through therapeutic stretches, physical adjustments, and exercises that correct a variety of problems.

As interest in canine rehabilitation grows, more clinics and independent therapists will offer noninvasive, drug-free therapies. With the help of workshops, books, videos, magazines, online courses, and DVDs, the basics of many bodywork techniques can be learned by anyone for use at home, in training, and whenever a dog might benefit.

Herbal Remedies for Healing Dog Injuries

Arnica (Arnica montana) is a small Alpine herb whose yellow flowers pack a powerful healing punch. If applied within a minute or two of a trauma injury, arnica tincture (an alcohol extract of the flowers) can stop pain and prevent bruising. Applied to older injuries, arnica stimulates capillary circulation and speeds healing.

But arnica is a controversial herb. Because it is a powerful heart stimulant, most American herbalists have been taught that arnica should never be taken internally or used on broken skin.

This cautious approach, say some experts, deprives users of arnica’s most important potential.

According to Ed Smith, a highly regarded herbal researcher and founder of Herb Pharm, an herbal products manufacturer, arnica is specifically recommended for internal injuries, such as those resulting from car crashes or surgery. Smith finds no justification for the warnings commonly placed on arnica products.

In addition to recommending arnica tincture for internal use in pets and people, giving 1 drop per 15 pounds of body weight every three to four hours as needed, he recommends applying it to bleeding wounds and other injuries to reduce swelling, pain, and bruising.

I know from experience that if you act fast enough, within a minute or two of injury, full-strength arnica tincture stops pain on contact and prevents swelling and bruising, which is why I keep bottles in back packs, handbags, fanny packs, glove compartments, medicine cabinets, and kitchen cupboards.

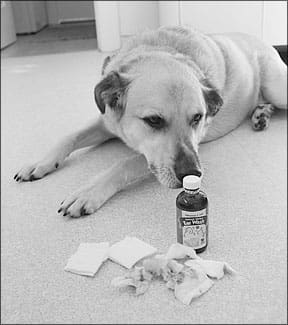

A few weeks ago when Chloe, my three-year-old Labrador Retriever, lay down in the woods, I knew she was hurt. When she stood, she couldn’t put weight on her left hind leg. I checked her foot for cuts and splinters, but it was fine.

Having no idea what had happened, I opened a bottle of Weleda arnica essence, gave her four drops on the tongue, and saturated her hurt leg from spine to toes, gently massaging her coat to help it reach the skin.

In less than a minute, my dog put weight on the injured leg and within five minutes, as we slowly walked home, her limp disappeared. After a day of crate rest and additional applications of arnica, Chloe resumed normal activities at a sedate pace until her monthly chiropractic appointment.

Arnica tincture can be diluted with water for use as a compress. Mix 1 tablespoon tincture with ½ cup water, saturate a towel or wash cloth, and hold it in place for 10 minutes every four to six hours. Homeopathic arnica tablets and ointments are popular sports injury treatments. These products are especially helpful for injuries near the eyes or mucous membranes, which an alcohol tincture would irritate. But for all other trauma injuries, arnica tincture is my first-aid first choice.

Rescue Remedy

Flower essences, such as the famous Bach Flower Remedies, are made by placing flowers in water, exposing them to sunlight, and bottling the result. These “energy” essences resemble homeopathic remedies but address emotional rather than physical symptoms. (See “Flower Essence Therapy For Dogs.”) The most famous such product is Bach’s Rescue Remedy, a blend of cherry plum, clematis, impatiens, rock rose, and star of Bethlehem essences. For decades, it has been given to people and animals to help them deal with shock, stress, and trauma. If your dog’s leg hurts, Rescue Remedy is an effective product to try.

Kris Lecakes-Haley, a Bach Flower Remedy practitioner at Animal Synergy in Phoenix, Arizona, calls Rescue Remedy one of the world’s top-selling stress relievers. “Even though Rescue Remedy and all of the Bach remedies are designed to work on the emotions,” she says, “they frequently have an immediate impact on physical injuries.”

At a dog show Lecakes-Haley attended, a Norwich Terrier was about to enter the show ring when he collided backstage with another dog. “He immediately began limping,” she says, “and I was amazed to see how many people came forward offering Rescue Remedy to the owner. She rubbed a few drops on his gums and paws and also on the impacted area. The dog shook, yawned, and then proceeded to prance limp-free into the arena. This is a classic example of Rescue Remedy in action.”

The same blend of essences, made by different manufacturers, is sold under the brand names Calming Essence, Five-Flower Formula, and Trauma Remedy.

Flower essences can be applied full strength a few drops at a time, diluted with water, added to herbal teas or hydrosols, or added to drinking water. Diluted flower essences can be sprayed in the air around the dog. Full-strength or diluted essences can be applied to paw pads and abdomen, dropped on the tongue, massaged into gums, applied to the inside ear’s bare skin, or placed on the nose.

The frequency of application matters more than quantity, and small amounts administered every hour or so can help any dog recover faster.

Herbs and Herbal Compresses for Pain Relief and Healing

Several herbs have anti-inflammatory properties that help dogs with arthritis and sports injuries. Boswellia (Boswellia serratta), bupleurum (Bupleurum spp.), cayenne (Capsicum frutescens), devil’s claw root (Harpagophytum procumbens), feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium), ginger (Zingiber officinale), turmeric (Curcuma longa), and yucca (Yucca baccata) have all been used to relieve joint pain and increase canine mobility and range of motion. Most herbalists recommend short “courses” of herbs, such as five days on and two days off, to monitor the animal’s response, adjust dosage, or switch from one herb to another.

Some herbal products are blended specifically for dogs with arthritis, knee or elbow problems, or stiff joints, such as the Australian remedy DGP (Dog-Gone Pain), Animals’ Apawthecary’s Alfalfa/Yucca Blend, and Nature’s Herbs for Pets blends for Injury Relief, Joint Relief, and other conditions. Follow label directions.

For the treatment of sprains, pulled leg muscles, and other acute injuries, Juliette de Bairacli Levy of Natural Rearing fame (see “A History of Holistic Dog Care“) recommends rest and the application of wraps soaked in cold water and vinegar. “The herbal remedies are comfrey or mallow,” she says. “Make a standard infusion of either herb and bathe the injured area before applying bandages.” A standard infusion is made by covering 1 or 2 teaspoons dried herb or 1 or 2 tablespoons fresh herb with 1 cup boiling water. Cover and let stand.

To make a cold compress for acute injuries and areas of inflammation, let the tea stand until cool, strain, add a tablespoon or two of raw cider vinegar if desired, then refrigerate or place in the freezer until cold. If you’re in a hurry, brew a double-strength tea and add ice cubes to cool it. Soak a small towel or washcloth, wring just enough to stop dripping, apply to the affected area, and hold in place. After a few minutes, soak the cloth again and reapply. Replace the compress as needed to keep the area cold for 10 to 15 minutes. Repeat the treatment every two to four hours.

Peppermint is a cooling herb with pain-relieving properties; cold peppermint tea makes an effective compress for acute injuries.

Hot herbal compresses are called fomentations. For chronic pain and injuries that do not present swelling or inflammation, let freshly brewed or reheated tea stand until it’s comfortably hot, not scalding, then strain and apply as described above. As soon as the fomentation cools, soak the cloth again and reapply. Continue warming the area for 10 to 15 minutes and repeat every two to four hours.

Cayenne is a warming herb with pain-relieving properties, especially if applied regularly, so cayenne added to any herbal tea works well as a fomentation. Just be careful not to touch your eyes or your dog’s eyes or mucous membranes with cayenne. If you do, apply any vegetable oil to remove it as water won’t wash away capsaicin (cayenne’s irritating ingredient).

For more on herbal remedies for your dog, see “Help Heal Your Dog with Common Herbs.”

Whole Dog Journal contributor CJ Puotinen lives with her husband, Joel, and Labrador Retriever, Chloe, in New York.

Dog Arthritis Treatments

Osteoarthritis is the number one cause of chronic pain in dogs, affecting one in five adult dogs, with the incidence more than doubling in dogs seven years and older. It is a degenerative disease that causes pain, loss of mobility, and a decreased quality of life. Signs of arthritis include stiffness when getting up or lying down, limping, slowing down on walks, pain after exercise, or reluctance to jump or climb steps. It’s important to recognize these signs and begin treatment early, to slow the progression and help preserve your dog’s quality of life.

When my dog, Piglet, was diagnosed with severe dysplasia in both elbows at a year old, I was told that, even with the surgery we did, she would develop arthritis in those joints. I gave her a daily glucosamine supplement, but knew of no other way to help her. By the time she was six, she was on daily NSAIDs (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, such as Rimadyl and Etogesic) to relieve the pain that otherwise caused her to limp. At the time, I thought I’d be lucky if she made it past the age of 10 before becoming too lame to walk.

It was then that I learned about the benefits of a natural diet, and began researching supplements that I could use to improve her condition. I switched her onto a raw, grain-free diet just after she turned 7, and within a few months, she no longer needed any drugs for pain.

As time went on and her joints continued to deteriorate, I tried more and more supplements and natural therapies, rotating between those that seemed to help, and replacing those that didn’t seem to make a difference. I was able to keep her off drugs until she was almost 12, then began adding them to her nutraceutical “cocktail.”

The net result? At age 15, her elbows are visibly deformed and vets cringe when they see her x-rays, but she still enjoys one- to two-hour walks every day. She no longer runs, but jogs along at a comfortable pace. I let her decide how far and how fast we go so that I don’t risk pushing her beyond her limits, but occasionally I have to convince her it’s time to head for home when we’re miles away and she still wants to keep going.

Following are the things that have helped my dog, and others like her.

Glucosamine and chondroitin

The first step in treating arthritis is the use of nutraceutical supplements called glycosaminoglycans (GAGs), also known as mucopolysaccharides. These include glucosamine (both the sulfate and the HCl forms) and chondroitin sulfate, from sources such as chitin (the shells of shellfish), green-lipped mussel (perna canaliculus), and cartilage. Also included in this category are the injectable forms sold under the brand names Adequan in the U.S. and Cartrophen (pentosan polysulfate) elsewhere.

GAGs are important because they actually protect the joint rather than just reduce symptoms, by helping to rebuild cartilage and restore synovial (joint) fluid. GAGs may also have some preventative effect on arthritis, though this is speculative.

Oral GAG products may be most effective if given separate from meals, though it’s fine to give them with food if needed. Always start with high doses so that you will be able to tell whether or not your dog responds. If you see improvement, you can then reduce the dosage to see if the improvement can be maintained at a lower dose.

If you don’t see any change within three to four weeks, try another supplement. Different dogs respond differently to the various supplements.

Brands that have worked for dogs I know include Arthroplex from Thorne Veterinary, Syn-Flex from Synflex America, Synovi-G3 from DVM Pharmaceuticals, Flexile-Plus from B-Naturals, and K-9 Glucosamine from Liquid Health. You can also use products made for people that contain ingredients such as glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and green-lipped mussel. The use of manganese in the supplement may help with absorption.

Injectable GAGs may help even more than the oral forms, and may work even when oral supplements do not. It’s very important to start with the full “loading” dose, following the instructions in the package insert, before tapering off the frequency to the least that is needed to maintain improvement (often one injection per month). You should continue to use the oral supplements as well.

It is interesting to note that the label instructions for Adequan say that it must be injected IM (intramuscularly), while Cartrophen is injected sub-q (subcutaneously, which is less painful and easier to do at home). Many vets believe that Adequan works just as well when injected sub-q as IM, and I have heard reports from people who have used this method effectively.

A related product is called hy-aluronic acid. It has been used with horses for many years, and more recently with dogs. In the past, it had to be injected into the joint under anesthesia in order to be effective, but newer oral forms have been developed that also work. You can use products made for dogs, horses, or humans, such as Synthovial 7 and Hyaflex (made by Hyalogic), Trixsyn from Cogent Solutions, and K-9 Liquid Health Glucosamine & HA.

Diet

Certain foods may increase inflammation and aggravate arthritis. Some people have found that eliminating grains from the diet improves their dogs’ symptoms, sometimes to the point that no other treatment is needed. In addition, plants from the nightshade family, including potatoes (not sweet potatoes), tomatoes, peppers (all kinds), and eggplant may aggravate arthritis.

Unfortunately, it’s not easy to avoid these foods unless you feed a homemade diet, where you control all the ingredients. The vast majority of dry foods contain grains, and those that do not often contain potatoes instead. There are a few brands that use only sweet potatoes or tapioca that would be worth trying for a dog with arthritis, to see if your dog improves. Canned foods usually have fewer carbohydrates than dry foods, so that might be another option to try, especially for smaller dogs where the higher cost of canned food is not such an obstacle.

Certain foods may help with arthritis: celery, ginger, alfalfa, tropical fruits such as mango and papaya, and cartilage are all good to add to the diet of a dog with arthritis. Remember that vegetables must be either cooked or pureed in a food processor, juicer, or blender to increase digestabilty by dogs, and fruits are more easily digestible when overripe.

A few people have reported that organic apple cider vinegar (with the “mother,” a stringy sediment comprised of enzymes) has provided some benefit when added to food or water. Be sure your dog is still willing to drink water with the vinegar added if you try it, or provide a separate, plain water source.

Weight and exercise

It’s extremely important when dealing with a dog who has arthritis to keep him as lean as possible. Extra weight puts added stress on the joints, and makes it harder for your dog to get proper exercise. If necessary, get an inexpensive postal scale and weigh your dog’s food to help you control his intake.

Carbohydrates supply the same number of calories as proteins do, but offer less nutritonal value to dogs. A low-carb, high-protein diet is better for a dog with arthritis than one that is high in carbs, which is more likely to lead to weight gain. Keep fat at moderate levels, to avoid weight gain from a high-fat diet and excess hunger from a diet that is too low in fat.

If your dog needs to go on a diet to lose weight, remember to reduce portions gradually, so the body doesn’t go into “starvation mode,” making it harder to lose weight.

Moderate, low-impact exercise, such as walking or swimming, is important for dogs with arthritis, as regular exercise will help maintain flexibility and well-developed muscles help to stabilize the joints. It’s important to prevent your dog from exercising to the point where he is more sore afterward. Swimming is an excellent exercise for dogs with arthritis, as it is non-weight-bearing, so your dog can exercise vigorously without damaging his joints. If your dog is unused to exercising, start slowly and work up only gradually, as he begins to lose weight and develop better muscle tone. Several short walks may be easier on him than one long one.

Natural anti-inflammatories

When your dog shows signs of arthritis, there are a number of natural anti-inflammatory supplements that you can try before resorting to medications.

First and foremost is fish oil, a source of the omega-3 fatty acids EPA and DHA, which reduce inflammation and provide other benefits to the body. Be sure to use fish body oil, such as salmon oil or EPA oil, not liver oil, which is high in vitamins A and D and lower in omega-3 fatty acids. (Also, liver oil would be dangerous at the high doses needed to fight inflammation).

Most fish oil gelcaps contain 300 mg combined EPA and DHA, and you can give your dog as much as 1 of these gelcaps per 10 lbs of body weight daily. If using a more concentrated product, containing 500 mg EPA/DHA, give 1 gelcap per 15-20 lbs of body weight daily. If using liquid fish oil, adjust the dosage so that you are giving up to 300 mg combined EPA/DHA per 10 lbs of body weight. Be sure to keep the product refrigerated so that it doesn’t become rancid.

You must supplement with vitamin E as well whenever you are giving oils, as otherwise the body will be depleted of this vitamin. Give around 100 IU to a small dog, 200 IU to a medium-sized dog, or 400 IU to a large dog daily or every other day. Vitamin E in high doses also has some anti-inflammatory effect.

High doses of vitamin C may help with arthritis. It’s best to use one of the ascorbate forms, such as calcium ascorbate or sodium ascorbate, rather than ascorbic acid, which is harder on the stomach and may be irritating to arthritis. Look for one that contains flavonoids as well, which also help to reduce inflammation. If desired, you can give vitamin C to bowel tolerance, which means increasing the amount every few days until your dog develops loose stools, then backing off to the next lower dosage.

Bromelain, an enzyme found in pineapples, has strong anti-inflammatory properties. It works best if given separately from meals (at least one hour before or two hours after). Its effectiveness may be increased when it is combined with quercetin, a flavonoid. There are many combination products available, or you can give each separately.

Certain herbs help to reduce inflammation. Some of the best ones to use for arthritis are boswellia, yucca root, turmeric (and its extract, curcumin), and hawthorn. Nettle leaf, licorice, and meadowsweet can also be used.

I usually rotate between various herbs and herbal blends. I’ve had the best results using liquid tinctures or glycerites when available, such as Animal’s Apawthecary’s Alfalfa/Yucca blend and Azmira’s Yucca Intensive. Other folks have had success using DGP (Dog Gone Pain, see “Safe Pain Relief,” WDJ May 2006). Note that willow bark is another herb often used for arthritis. It is a relative of aspirin that may be easier on the stomach, but should still not be combined with other NSAIDs.

SAM-e (s-adenosylmethionine), a supplement that is used to support the liver, can also reduce pain, stiffness, and inflammation caused by arthritis. It works best when given apart from food, and when combined with a B-complex vitamin.

Supplements that have worked for other people who have dogs with arthritis include MSM, Duralactin (this product is derived from milk, so creates digestive discomfort in some dogs), and Wobenzyme. There are also some newer herbal blends being marketed as replacements for NSAIDs, including Kaprex from Metagenics and Zyflamend from New Chapter, but I have not heard much feedback on them.

Other natural therapies

Dogs with arthritis often respond to acupuncture and chiropractic treatments. Massage therapy can also be very beneficial, and is something you can learn to do yourself at home. Hydrotherapy using warm pools or underwater treadmills is becoming increasingly popular and can be very helpful, particularly for dogs recovering from surgery or injury.

If acupuncture helps your dog, you may want to consider gold bead implants, which are a form of permanent acupuncture.

Many dogs respond to chiropractic treatments, which can be especially beneficial if your dog tends to become “misaligned” due to favoring one limb.

Warmth can help reduce arthritis pain. Thick, orthopedic beds that insulate your dog from the cold floor or ground as well as cushioning the joints provide a lot of comfort. There are also heated dog beds available, but be sure that the cords cannot be chewed. A product called “DogLeggs” can be custom-made to keep elbows, hocks, or wrists (carpus) warm.

Some people have reported success using the homeopathic treatments Traumeel and Zeel by Heel Biotherapeutics.

DLPA

Eventually, no matter what you do, your dog may require treatment for chronic pain. There is one more nutraceutical that can help with this: dl-phenylalanine (DLPA), an amino acid that is used to treat both depression and chronic pain.

The most common dosage range for dogs is 1 to 5 mg/lb (3 to 10 mg/kg) of body weight, but I have seen dosage recommendations as high as 5 to 10 mg per pound (2 to 5 mg/kg), two or three times a day. In humans, very high doses may cause numbness, tingling, and other signs of nerve damage, so be on the watch for any signs that your dog may be experiencing these if using such high doses. It takes time for DLPA to begin to work, so it must be used continuously rather than just as needed. Often, however, you needn’t continue to give DLPA daily once it has taken effect; sometimes it can be given as little as one week per month to retain results. It is safe to combine DLPA with all other arthritis drugs, but do not combine DLPA with MAOI drugs such as Anipryl (selegiline, l-deprenyl), used in the treatment of Cushing’s Disease and canine cognitive dysfunction, or amitraz (found in tick collars).

I use Thorne Veterinary’s Arthroplex, which includes DLPA, because it makes it easy to give the proper dosage for a small- or medium-sized dog, but you can use human DLPA supplements for larger dogs. They are available in 375 mg and 500 mg capsules.

Kay Jennings, who lives with three dogs in Bristol, England, has a young German Shepherd Dog who began limping as a puppy, and was diagnosed with elbow dysplasia. “I’ve kept my lad active and pain-free using just DLPA plus Syn-Flex, and my arthritic Border Collie too,” she says. “It’s so effective that they can both take it just every other week and its residual effect keeps them covered for the other week.”

Jennings also has a working sheepdog who required higher doses initially. “My Polly had to start at 1,000 mg a day (she weighs 45 lbs). I was about to write it off with her at 500 mg a day, assuming she was one of those for whom it doesn’t work. I found a starting dose of any less than 1,000 mg made no difference to her even after a couple of weeks. Once we hit the right dose it worked within three days, and after a few weeks I could reduce to a lower level (500 mg a day) that still provided relief. After several months at this level, I was able to reduce her further, to 250 mg/day, and even put her on the week-on-week-off schedule that has worked for my other dogs.

“I have to say, I’ve found DLPA to be remarkably effective: Polly is now 14, and doing better than she has for some time. Kiri, my Border Collie, has recently (at the age of 11!) started doing a bit of obedience again, and Ziggy, the GSD, is still totally sound and very active, when his vet was convinced he’d need NSAIDs for his entire life just to be able to get about.”

NSAIDs

There is much controversy about the use of NSAIDs, such as Rimadyl (carprofen), Etogesic (etodolac), Deramaxx (deracoxib), Metacam (meloxicam), and aspirin. This is due to their potential for harmful side effects, which include not only gastric ulceration but also liver and kidney failure, leading to death in some cases, sometimes after only one or two doses.

While there is no doubt that these drugs can be dangerous, they do have their place in maintaining quality of life when nothing else works. Inflammation creates a vicious cycle, breaking down cartilage and causing pain that restricts activity, which leads to weight gain and muscle loss, further restricting your dog’s ability to exercise and enjoy his life. Natural anti-inflammatories can do a great deal to help, but in the end, they are not as powerful as drugs.

There are precautions you can take to make the use of NSAIDs safer, though you cannot eliminate their risk. First, it’s always a good idea to have blood work done before starting any NSAID, and every few months thereafter when using them regularly, to check for underlying liver or kidney disorders that would contraindicate their use.

Second, you should always give NSAIDs with food, never on an empty stomach, to help prevent the gastric ulceration that is a very common side effect.

Third, never combine NSAIDs with each other, or with prednisone, which greatly increases the chance of ulcers and other dangerous side effects.

Fourth, discontinue immediately and contact your vet at the first sign of any problem, which may include lethargy, lack of appetite, drooling, vomiting, diarrhea, difficulty swallowing, jaundice (yellowing of the whites of the eyes), increased drinking and urination, or any behavioral changes such as aggression, circling, or ataxia (loss of balance or coordination).

Last, be very cautious when switching from one NSAID to another. If possible, wait at least a week in between, particularly if switching from one of the non-COX selective products, such as aspirin, to one of the newer, COX-2 selective drugs, such as Deramaxx.

Anecdotal reports indicate that Rimadyl and Deramaxx appear more likely to cause serious problems when first started than other NSAIDs. Be particularly watchful if you use either of these drugs, or ask your vet for another option.

There is also a drug you can give to help reduce the chance of gastric ulcers, called Cytotec (misoprostol). This is a human drug that can also be used for dogs. It helps to mitigate the effects of COX inhibition that are responsible for damage to the intestinal lining by NSAIDs.

Another prescription medication that can be helpful is sucralfate, which is used to heal ulcers. Sucralfate interferes with the absorption of all medications, so it must be given at least two hours before or after you give other meds.

Herbs such as slippery elm and marshmallow may also help to protect the stomach and intestines, though they’ve never been tested specifically with NSAIDs. One product that contains both is Phytomucil from Animal’s Apawthecary.

Tramadol

When drugs are needed, ask your vet about using tramadol (Ultram), a synthetic opioid that provides paiin relief without sedation or addiction and is safer than NSAIDs. Tramadol can be used in place of NSAIDs, though it is mostly for pain and has limited anti-inflammatory effect. It can also be combined with NSAIDs to increase pain control or lower the dosage needed, or pulsed periodically to give the body a break from taking NSAIDs.

Tramadol can be given continuously or used on an as-needed basis. It is less likely to create dependence than narcotics, but you should still wean off slowly rather than discontinuing abruptly if used long-term. Tramadol can cause constipation; if this is a problem, you can give your dog a stool softener to help. I’ve found that the price of tramadol varies significantly; Costco has the best prices I’ve seen (non-members can order prescriptions from Costco and they will ship for $2).

Gunner is an 11-year-old Rottweiler belonging to Sheila Jones of Highland, Michigan. He was diagnosed with elbow dysplasia at age two, and originally put on Deramaxx as needed, but was later switched to fish oil and yucca, which helped until a couple of years ago, when he became lame and needed something more to control his pain.

“I started him on tramadol at a low dose, but have worked up over time to 150 mg twice per day (⅔ of his maximum dose), and I add yucca root extract in liquid form when he needs an additional boost,” Jones says. “He also gets 2,000 mg of vitamin C twice per day.”

Jones is pleased with how well tramadol has worked for Gunner. “He is a little slow getting up in the mornings, but overall I believe he is doing very well. I am in contact with the owners of three of his littermates, and he seems to be doing the best of them. He still plays with our younger Rottie, and with his indestructible ball regularly. On days that he overdoes it, I give him a little extra tramadol.” Note: Dogs should not take Ultracet, a combination of tramadol and acetaminophen (Tylenol), which can be dangerous for dogs.

Other medications

There are a few other medications that can be used for dogs’ chronic pain, when NSAIDs can’t be used, to decrease the dosage needed, or when more relief is needed. Most antidepressants, such as Elavil (amitriptyline) and Prozac (fluoxetine), offer some pain relief. Be careful about combining these drugs with Tramadol. See “Chill Pills,” July 2006, for more information.

Amantadine offers little in the way of pain control itself, but helps potentiate (increase the effectiveness of) other drugs used to control pain. It is inexpensive and can be used concurrently with Tramadol, NSAIDs, corticosteroids, gabapentin, and opioids. Neurontin (gapabentin) is an anti-convulsant medication also used to treat chronic pain. It can be combined with other medications, but is expensive.

When pain cannot be controlled in any other way, narcotics may be used. Hydrocodone can be combined with NSAIDs for greater relief. Vicodin (a combination of hydrocodone and acetominophen) is sometimes used, though acetominophen can cause liver failure in some dogs, and should not be combined with NSAIDs due to the danger of toxicity from acetominophen. Codeine can also be used, though it’s not as effective. Oxycodone or a fentanyl (Duragesic) patch can be used, but tend to have more of a narcotic effect and so are best used only for short periods, though even that may make a big difference. All narcotics are addictive, so they are best used intermittently rather than every day.

Lastly, there is some possibility that doxycycline may be helpful. This may be due to the fact that joint infection is common with arthritis, or because it has some anti-inflammatory effect of its own.

The future can be bright

There are an endless number of supplements and therapies that claim to help with arthritis, but the ones noted here are those that, in my experience, have the best records of success. It’s important to keep trying different combinations to find what works for your dog, as each dog is an individual, and what works for one may be different from what works for another.

At age 15, Piglet is on a grain-free raw diet. I also give her Arthroplex (which includes glucosamine, green-lipped mussel, DLPA, boswellia, bromelain, and vitamin C), high dose fish oil, turmeric, SAM-e, and vitamin E daily. I alternate between giving her herbal Senior Blend and Alfalfa/Yucca blend (both from Animal’s Apawthecary). I give her Metacam, and one dose of tramadol daily to help with walks. She is also on sertraline (Zoloft) for anxiety, which may help with pain as well.

This combination of natural and conventional treatment has kept Piglet going for years longer than I thought she would – longer even than I dared hope. She is staring at me now, reminding me that it’s time for her walk, still the highlight of her day, and something she insists upon, even when it is pouring down rain. I am delighted to oblige.

- Start your dog on glucosamine-type supplements at the first sign of arthritis, or even before.

- Keep your dog lean to reduce wear and tear on her joints, and encourage moderate exercise that doesn’t make lameness worse.

- Use diet and natural supplements to control arthritis pain before resorting to drugs.

- Maintain a health journal for your dog, to record which treatments you try, at what dosages, and how well they work for your dog.

Download The Full February 2007 Issue PDF

Join Whole Dog Journal

Already a member?

Click Here to Sign In | Forgot your password? | Activate Web AccessGiving Back

Dont have a dog right now. Mokie, the Chihuahua Ive had for the past three years the one who used to be my sisters dog is now living with my other sister. For complicated reasons, Im splitting my time between two homes, in two towns, and dragging a dog through all this just isnt practical or fair. Mokie vacationed with Pams family while I was moving, and fit into their home and hearts so well, we decided it was best for him to stay there.

250

I do miss that little muffinhead, though, and miss having a dog with me at all times. To cope, Im getting my dog-hair and dog-breath fix at an animal shelter thats close to one of my homes.

Im lucky; the animal shelter is a brand-new and spacious facility, the culmination of years of fundraising and planning by its director and board. The staff has been reenergized by the move to the new location; everyone seems highly committed to doing whats best for the animals. And volunteers are in short supply, so anything Ive offered to do has been eagerly accepted. Im walking dogs, washing dogs, and training dogs to sit quietly in front of their cage doors when approached. The other day, as I was doing this, two young girls who were also volunteering came over to watch and within an hour (and a pound of canine cookies) they had every dog in the shelter sitting or lying down quietly the moment someone stepped in front of them.

So, while I do certainly miss having my own dog, and would love to take four or five home with me, Im going to try to wait until I get my life better stabilized. The company of dogs has sustained me so much over my lifetime, starting before I can even remember. My resolution for 2007 is to spend time trying to give something back to dogs not just one dog in gratitude.

Another good thing Ive been able to offer the shelter is a bunch of dog food! My office always becomes a bit unmanageable around the time of Whole Dog Journals annual dry dog food review, which is featured in this issue. Its a pleasure on many levels to pack all the food into my car and haul it to the shelter.

This was the tenth time I have reviewed dry dog foods for Whole Dog Journal. In 1998, when the magazine was first published, I was hard-pressed to find more than a dozen or so foods that contained whole meats, grains, and vegetables. Today, there are scores of these foods on the market, and the variety and quality level continues to rise; check them out, starting on page 6.

This issue also contains a welcome article from Greg Tilford, a highly respected expert on herbal medicine for animals (see page 16). Greg has offered to answer some of our readers questions about herbal remedies for dogs. You can e-mail your question to Greg at WDJHerbQuestion@aol.com. Hell select a few and well publish his responses in an upcoming issue. Of course, this issue also contains the usual practical advice on

positive training and holistic health. I hope you enjoy it.

Whole Dog Journal’s 2007 Dry Dog Food Review

Not all that long ago, selecting a dry food for your dog was pretty simple. What brand (singular) did your local pet supply store carry? What size bag did you want? And would you like some help out with that, ma’am?

Today, making a choice of dry dog foods can be immensely more complex that is, if you buy into the notion that not all “complete and balanced” diets are equal. There are millions of people, after all, who think that all dog foods are alike, and that you’d have to be an idiot to spend $30 or $40 or $50 on the same-sized sack of what you can buy for $7.99 at WalMart.

We’re here to testify that there is a difference between those $7.99 foods and the high-dollar products. And, while the task isn’t exactly brain surgery, choosing the best foods for your dog requires your attention and consideration of numerous factors.

First things first

Our task today is to dispense with a common misconception one so prevalent, that even many veterinarians swear it’s accurate. Many people believe that all dog foods that are labeled as “complete and balanced” are equally appropriate and healthful for your dog. It’s so not true.

“Complete and balanced” sounds good unambiguous in its assertion that a product so labeled contains everything, in just the right amounts and proportions, that a dog needs to live a long and healthy life. But, as Bob Dylan sings, “The truth was far from that.”