EPI IN DOGS: OVERVIEW

1. When you see or hear about an apparently starved (or extremely thin) dog, please let the owner know about EPI. Few people know that it can affect any breed.

2. If your dog’s digestion is poor, with frequent diarrhea, consider having him tested for EPI. Visible symptoms of the disease may not appear until 80 to 95 percent of the pancreas has atrophied. Early diagnosis and treatment improve his prospects.

Kanis Fitzhugh, a member of the Almost Home organization, knew she had to rescue Pandy, an extremely thin and seemingly vicious four-year-old Dachshund. Pandy had been relinquished to a shelter in Orange County (California), who turned her over to Southern California Dachshund Rescue. Deemed people- and animal-aggressive, Pandy appeared to have been starved, and weighed just 13 pounds. Fitzhugh thought the dog deserved a break, and brought Pandy home in May 2007.

During the first couple of weeks in her new home, Pandy managed to pull a chicken down from the counter and proceeded to eat the entire bird, including bones, plastic tray, and grocery bag, in less than the 10 minutes that Fitzhugh was out of the room. Pandy was rushed to the vet and emergency surgery was performed, as the bones had ruptured her stomach lining in three places. Luckily, she survived.

Pandy’s voracious appetite, large voluminous stools, and aggressive disposition were all caused by a medical condition called exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (EPI). With Fitzhugh’s loving care, including enzyme supplements and a change of diet, Pandy stabilized. Within a year, Pandy had transformed into a beautiful, funny, 26-pound Dachshund who gets along great with all the human and animal members in the Fitzhugh household.

What is Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency?

Exocrine Pancreatic Insufficiency, or EPI, also referred to as Pancreatic Hypoplasia or Pancreatic Acinar Atrophy (PAA), is a disease of maldigestion and malabsorption, which when left untreated eventually leads to starvation. One of the major difficulties with this disease is in the prompt and accurate diagnosis. Astonishingly, visible symptoms may not appear until 80 to 95 percent of the pancreas has atrophied.

There are two primary functions of the pancreas:

(1) Endocrine cells produce and secrete hormones, insulin, and glucagons.

(2) Exocrine cells produce and secrete digestive enzymes.

EPI is the inability of the pancreas to secrete digestive enzymes: amylase to digest starches, lipases to digest fats, and proteases to digest protein. Without a steady supply of these enzymes to help break down and absorb nutrients, the body starves. When EPI is undiagnosed and left untreated, the entire body is deprived of the nutrients needed for growth, renewal, and maintenance. In time, the body becomes so compromised that the dog either starves to death or dies of inevitable organ failure.

Incomplete digestion causes the continual presence of copious amounts of fermenting food in the small intestine. This can lead to a secondary condition that is common in many EPI dogs, called SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth). If an EPI dog has a lot of belly grumbling/noises, gas, diarrhea, and sometimes vomiting, she most likely has SIBO.

The condition occurs when the “bad” bacteria that is feeding on the fermenting food overpopulates the tissue lining the small intestine, further impairing the proper absorption of vital nutrients and depleting the body’s store of vitamin B12. Treatment of SIBO includes a course of antibiotics, to eliminate the bad bacteria. Treatment may also include supplemental cobalamin (B12) injections that help reestablish friendly bacteria colonies, which in turn helps inhibit the malabsorption.

Severity of the disease may vary, making it even more difficult to diagnose. EPI can be subclinical (no recognizable symptoms) for many months, sometimes even years, before it worsens and becomes noticeable. The symptoms can be exacerbated by physical or emotional stress, change of food or routine, and/or environmental factors. The most common symptoms include:

– Gradual wasting away despite a voracious appetite.

– Eliminating more frequently with voluminous yellowish or grayish soft “cow patty” stools.

– Coprophagia (dog eats his own stools) and/or pica (dog eats other inappropriate substances).

– Increased rumbling sounds from the abdomen, and passing increased amounts of gas.

– Intermittent watery diarrhea or vomiting.

Due to the lack of absorbed nutrients, the body starves: muscle mass wastes away, and bones may also be affected. An EPI dog’s teeth may be slightly smaller, and older EPI dogs appear to have a higher incidence of hip dysplasia. Every part of the body is at risk, even the nervous system (including the brain), which in turn wreaks havoc with the dog’s temperament. Some EPI dogs exhibit increased anxiety, becoming fearful of other dogs, people, and strange objects.

With hunger as an overwhelming force, many dogs act almost feral. Desperately seeking vital nutrition, many ingest inappropriate items, but nothing gets absorbed. As the disease progresses, the deterioration becomes quite rapid. Some dogs lose interest in any activities, preferring to just lie down or hide somewhere. Many owners of EPI dogs become increasingly frustrated, as they feed more than normal amounts and yet their dogs continue to waste away before their eyes.

Since chronic loose stools are usually the first visible symptom in an EPI dog, most vets will prescribe an antibiotic to destroy what they suspect to be harmful intestinal bacteria. Owners are happy because the problem appears to go away, at least for a while. No one has any reason to investigate further, until the loose stools return or the dog starts losing weight, and then the merry-go-round cycle begins. Vet visits become numerous and costly, and one possible diagnosis after another is suggested. Expenses may include testing (and retesting) for giardia, coccidiosis, and other parasitic diseases; x-rays; ultrasound; MRI; antibiotics; and even surgery.

EPI Testing for Dogs

Until recently, EPI was most prevalent in German Shepherd Dogs. For this reason, a vet may fail to consider EPI as a possible diagnosis in other breeds and not pursue EPI testing: a trypsin-like immunoreactivity (TLI) blood test. TLI measures the dog’s ability to produce digestive enzymes. The test is done following a fast of 12 to 15 hours, and costs about $100.

Although other laboratories can run the TLI test, most blood samples are analyzed at Texas A&M University. The lab recently revised its reference ranges: values below 2.5 are now considered diagnostic for EPI. Results between 3.5 and 5.7 may reflect subclinical pancreatic disease that may ultimately lead to EPI. When values are between 2.5 and 3.5 µg/L, Texas A&M recommends repeating the TLI test after one month, paying particular attention to the fast before the blood sample is collected.

Even when a dog tests positive for EPI, it is important to retest TLI after the dog stabilizes following treatment. For example, chronic inflammation can put such a strain on the pancreas that the production of digestive enzymes ceases or is greatly reduced. Consequently, when the TLI blood test is analyzed, it accurately depicts lack of enzyme production, even though the dog may not actually have EPI. In this case, it is important for the dog to be treated with pancreatic enzymes until his condition is stable. Enzyme treatment breaks down the food, allowing the stressed albeit non-EPI pancreas to recuperate and, in time, start producing the enzymes needed to digest foods.

Dorsie Kovacs, DVM, of Monson Small Animal Clinic in Monson, Massachusetts, has seen some young dogs with false-positive EPI readings. Even when they display the lighter-colored “cow patty” stools, something other than EPI may be the cause. Sometimes a food allergy or an overabundance of bad bacteria has irritated or inflamed the pancreas, temporarily inhibiting enzyme production. In these situations, says Dr. Kovacs, it’s important to put the dog on a pancreatic enzyme supplement for two months, allowing the stressed pancreas to heal. The dog should then be retested to either confirm or rule out EPI.

In addition, Dr. Kovacs says, “It is also important to introduce good gut flora (bacteria) by adding yogurt, green tripe, or supplements such as Digest-All Plus (a blend of plant enzymes and probiotics). Good gut flora should continue to be maintained with supplements even after the inflamed or irritated pancreas has healed.” Dr. Kovacs has also noticed that some dogs with food allergies (especially dogs who are fed kibble) show rapid improvement when their diets are switched to raw or canned food. Raw meats contain natural enzymes, and fresh vegetables support the growth of good bacteria in the dog’s gut.

Managing a Dog’s EPI

Most dogs with EPI can be successfully treated and regulated, although customizing the dog’s diet and supplements may involve much trial and error.

Enzyme supplementation is the first step in managing EPI. The dog will need pancreatic enzymes incubated on every piece of food ingested for the remainder of his or her life. The best results are usually obtained with freeze-dried, powdered porcine enzymes rather than plant enzymes or enzyme pills. Plant enzymes and enzymes in a pill form do work for some, though with enzyme supplements, as with diet, much is dependent on the individual EPI dog. Some of the most widely used prescription enzyme supplements are Viokase, Epizyme, Panakare Plus, Pancrease-V, and Pancrezyme. Bio Case V is a non-prescription generic equivalent.

Enzyme potency is measured in USP units. Prescription enzyme powders range from 56,800 to 71,400 units of lipase; 280,000 to 434,000 units of protease; and 280,000 to 495,000 units of amylase per teaspoon.

Pancreatic enzymes are also available as generic pancreatin. Strengths of 6×10, 8×10, etc., indicate that the dosage is concentrated. Thus, a level teaspoon of pancreatin 6×10 contains 33,600 units of lipase and 420,000 units of protease and amylase, comparable to prescription enzyme products.

Some EPI dogs have allergies and cannot tolerate the ingredients in the most common enzyme supplements. Those owners learn to develop alternative methods such as using plant enzymes, or a different source of pancreatic enzymes such as beef-based (rather than porcine-based). Raw beef, pork, or lamb pancreas can also be used. One to three ounces of raw chopped pancreas can replace one teaspoon of pancreatic extract.

The starting dosage of prescription enzymes is usually one level teaspoon of powdered enzymes per cup of food. As time goes on and a dog stabilizes, many owners find that they can reduce the amount of enzymes administered with each meal, sometimes to just ½ teaspoon, although some EPI dogs require an increased dosage of enzymes in their senior years.

Enzymes need to be incubated, meaning that you add them to moistened food prior to feeding, letting them sit on the food at room temperature for at least 20 minutes. Some owners find that incubation up to an hour or more works even better. Too often, EPI owners are instructed that enzyme incubation is not necessary; however, some dogs will develop blisters or sores in their mouths from the enzymes when they are not first incubated on the food.

How do you judge what works best for your dog? When dealing with EPI, everything is gauged by the dog’s stool quality. EPI dog owners are always on “poop-patrol.” The goal is to obtain normal looking, chocolate brown, well-formed stools. When your dog produces something other than normal poop, it indicates she is not properly digesting her food. Sometimes longer enzyme incubation helps. Other times using more or less enzymes (since too little or too much enzymes can both cause diarrhea), changing the diet, treating a flare-up of SIBO, or starting a regimen of B12 shots solves the problem. Make only one change at a time. It is advisable to keep a daily journal as it may help you to identify the cause of a flare up or setback.

Prescription enzyme supplements can be very expensive. A $5,000 per year price tag for enzymes is not uncommon for a large dog – but don’t panic! There are several ways to reduce this cost. My 40-pound Spanish Water Dog has the dubious honor of being the first of her breed ever to be positively diagnosed with EPI. When the TLI results came in, I felt like my world came crashing down. Izzy is my once-in-a-lifetime companion, and was very sick. Using information my vet gave me, I estimated that the enzymes she needed were going to cost me $1,200 a year. She was just over a year old at the time, with an expected life span of 13 to 15 years. Eeek!

Today those enzymes cost me a mere $200 a year. How? I joined an EPI support group and learned what others do to better manage the ongoing care of their EPI dogs. I buy enzymes from an EPI enzyme co-op that purchases enzymes in bulk and passes the savings on to owners who have a veterinarian-confirmed EPI dog. The savings from these bulk purchases can be quite substantial. (For both groups, see “Resources for Products Mentioned in this Article,” page 22.) Today, Izzy is a plump, active, happy dog who gives me more joy than any dog I’ve had in my 55 years. I would have paid whatever it cost to help her, but not everyone has this option.

Another solution that can dramatically save money is to obtain raw beef, pork, or lamb pancreas. Ask your butcher if he can get fresh pancreas, or check with meat inspectors in your state to find out if and where you can obtain fresh pancreas. A letter from your vet explaining why you need fresh pancreas may allow you to purchase it from a slaughterhouse. Fresh beef pancreas can also be ordered from suppliers such as Hare Today and Greentripe.com.

The suggested dosage of raw pancreas is 3 to 4 ounces per 44 pounds of the dog’s weight daily. The pancreas can be blended or finely chopped, then frozen into either cubes in an ice tray or “calculated by the dog’s weight” single meal amounts in Ziploc bags. Raw pancreas can be frozen for several months without losing potency. When ready to use, thaw and serve the raw pancreas with the dog’s food.

A very important factor about enzymes – whether using raw pancreas, powdered pancreatic enzymes, or pills – is that all digestive enzymes work best at body temperature. Cold inhibits the enzymatic action while heat destroys it. Never cook, mix with very hot water, or microwave raw pancreas or supplemental enzymes.

Antibiotics are the next line of defense, in order to combat SIBO (bad bacteria growth that overtakes the growth of good bacteria), the secondary condition that frequently accompanies EPI. Tylosin (Tylan) or metronidazole (Flagyl) are the most commonly prescribed antibiotics, and they are usually given for 30 days. Some dogs have trouble with metronidazole due to possible side effects; in that case, Tylan is given. Be warned: Tylan is bitter-tasting, and many dogs refuse to eat their meals when it’s added. There are tricks to deal with this. Some put the Tylan powder in gelatin capsules; I camouflage it for my dog by inserting the required dose in a small chunk of cream cheese. Not all EPI dogs can tolerate dairy, so the camouflage method should depend on the individual dog’s tolerance.

B12 (cobalamin) injections are needed if the dog has very low serum cobalamin. A blood test is required to determine this, costs about $31, and is best done simultaneously with the TLI test. Many EPI dogs cannot replenish B12 levels on their own, so B12 injections are used. B12-complex formulas are not recommended since they contain much lower concentrations of cobalamin and appear to cause pain at the injection sites. Generic formulations of cobalamin (B12) are acceptable.

The recommended cobalamin dosage is calculated according to the dog’s weight and may be found on Texas A&M University website (see page 22). Your vet can show you how to give your dog subcutaneous (beneath the skin) B12 injections. What seems to work best are weekly injections for the first six weeks, then biweekly (every other week) injections for the next six weeks, and finally monthly B12 injections.

Feeding Dogs with EPI

A common saying among those whose dogs have EPI is, “If you’ve met one EPI dog, then you have met just one EPI dog.” Even with pancreatic enzyme supplements, much of the health and well-being of each EPI dog depends on his diet. Sometimes all that’s needed are supplemental enzymes and the standard recommended dietary modifications: no more that 4 percent fiber and no more than 12 percent fat (on a dry matter basis).

Sometimes it’s much more complicated! Some dogs can tolerate much more fat. My dog, Izzy, for example, does extremely well on grain-free kibble with 22 percent fat content, well above the 12 percent range. Other dogs cannot tolerate even as little as 12 percent fat. The same applies to the fiber content. Some EPI dogs have unrelated food allergies, further limiting their diet.

Many dogs with EPI thrive on raw diets and some owners find that a raw diet is the only one that works for their dogs. Conversely, other EPI dogs cannot tolerate raw diets. Some owners successfully feed grain-free kibble, some make home-cooked meals for their dog, while others feed a combination of commercial and homemade. When adding to or adjusting a diet, feed the dog tiny chunks of raw carrot with the diet. These carrot pieces will present themselves in the stools (for better or worse) of that meal’s elimination. This helps you understand which foods/vitamins, etc., work well together and which don’t.

Recommendations keep evolving and changing with new research, as well as the feedback from networks of owners of EPI dogs. A recent change in feeding recommendations concerns dietary fat. Multiple studies from the past decade indicated that a fat-restricted diet is of no benefit whatsoever to the EPI dog. A 2003 paper by Edward J. Hall, of the University of Bristol in England, states that there is experimental evidence to show that the percentage fat absorption increases with the percentage of fat that is fed. This may explain why some EPI dogs can tolerate higher concentrations of fat. For those dogs who cannot tolerate more than 12 percent fat, this may mean that the fat content needs to be increased very gradually, or perhaps that certain types of fat may be tolerated better than others. Much more research is needed to answer these questions.

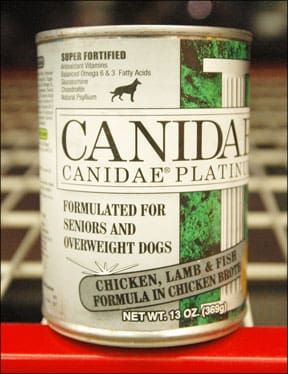

Veterinarians usually recommend an initial diet of a prescription or veterinary food, such as Hill’s Prescription Diet w/d, i/d, or z/d Ultra Allergen-Free; Royal Canin’s Veterinary Diet Canine Hypoallergenic Diet or Digestive Low Fat Diet.

Prescription diets that are made with hydrolized ingredients (carbohydrates and proteins that have been chemically broken down into minute particles for better absorption in the small intestine, leading to more complete digestion, better/faster weight gain, and firmer stools) appear to work for many EPI dogs.

However, these diets are usually starch-based (often almost 60 percent carbohydrates on a dry matter basis); the digestive system of a dog is designed more for fats and protein than for starches, which may be why many EPI dog owners achieve better results by reserving prescription diets for short-term use and feeding other diets over the long haul.

The best results for managing EPI requires combining veterinarian advice with the experience of actual EPI dog owners. Too many times, managing EPI can be a real roller coaster ride! For example, initial research studies showed that supplemental enzyme powders needed to incubate on the food. Additional research studies then suggested that food incubation with enzymes was no longer necessary. Consequently, some EPI dogs developed mouth sores, so owners are again being advised to let the enzymes incubate to prevent this side effect. Until the causes and effects of this disease are better understood, it will continue to be managed via trial and error.

Canine Pancreatic Insufficiency Feeding Guidelines

Enzymes should be mixed with about one to two ounces of room-temperature water per teaspoon of enzymes, then added to the food and allowed to incubate for 20 minutes or more. A couple of tablespoons of room temperature kefir or yogurt (or some other “sauce”) may be used instead of water to mix the enzymes. Once an EPI dog is stable, some owners find that they can “cheat” and give their dog a smidgeon of a treat without any enzymes on it. Others find the least little crumb ingested without enzymes will cause a flare-up.

If possible, feed two to four meals a day, taking into consideration whether the dog’s condition has stabilized and whether the family’s schedule can accommodate multiple feedings. Feeding smaller, more frequent meals puts less stress on the EPI dog’s digestive system.

At first calculation, many owners of EPI dogs wonder if they can sustain the added expense of all these “special foods” in addition to the enzymes. It may take many attempts to find just the right diet for a dog with EPI that is also affordable by the owner, but it can be done. Following are some suggestions and techniques that EPI dog owners have successfully used.

– Kibble or canned: Many EPI owners who feed commercial kibble or canned dog food have found more success when feeding a grain-free product. Much depends on the individual dog.

When feeding kibble, many owners let the food and enzymes incubate until the food has an oatmeal-like consistency. Some even grind the kibble to allow for more surface contact with the enzymes. Some also add a teaspoon of pumpkin or sweet potato, which may help firm stools and reduce coprophagia; plus, both ingredients are packed with vitamins C and D. Sweet potato is also an excellent source of vitamin B6.

– Combination kibble and homemade: Many owners feed a combination of commercial food and raw or home-cooked. EPI owners generally mix foods at a ratio of 20 to 80 percent. As always with an EPI dog, enzyme supplements should be mixed in with the wet portion of the food at room temperature and allowed to incubate. Depending on each individual dog’s tolerance, any variety of meats and fish may be used. Sources of proteins can include beef, chicken, turkey, pork, venison, rabbit, lamb, canned or cooked salmon, and jack mackerel, as well as eggs, yogurt, and cottage cheese. Organ meats, such as liver, kidney, and heart should also be included in the diet. Green tripe is another good option. Variety is key! Again, incubate the food with the enzymes and feed two to four times daily, depending on your individual dog’s needs and your own schedule.

– Raw and home-cooked: Over the past few years, many owners have been able to stabilize their EPI dogs by feeding a raw diet. Raw food has the innate advantage of maintaining natural food enzyme activity that aids digestion. Many vets disapprove of feeding a raw food diet, especially to compromised dogs (possibly exposing them to further complications), while other vets suggest that raw is best for an EPI dog. There have been many anecdotal cases of dramatic improvement when the owners feed their EPI dog a raw diet, especially when all else fails.

Most EPI dogs cannot handle the 20 to 25 percent raw bone content in the diet that is commonly fed to normal dogs. With EPI dogs, it’s smart to start with only 10 to 12 percent of bone. Some dogs still have difficulty digesting this amount of the bone and the ratio will need to be reduced even further, to 3 to 5 percent bone. Note we are talking about the amount of actual bone, not the amount of raw meaty bones, which are usually at least half meat.

Vegetables may be a large or small portion of the diet, or not included at all, depending on the individual dog’s tolerance. If included, they should always be mashed. Organ meats are usually recommended at 10 to 15 percent of the EPI diet, but again, not all dogs can tolerate this.

Supplements for an EPI Diet

Whether you feed dry, canned, home-cooked, raw, or any combination, there are many other ingredients that may be added to provide additional benefits for EPI dogs.

Most EPI dog owners add coconut oil and/or wild salmon oil to their dogs’ diet. Many EPI dogs cannot digest other fats and develop dry, itchy skin or dry, brittle coats. Coconut oil contains medium-chain triglycerides (MCTs). Most vegetable oils have longer chain triglycerides, called LCTs. MCTs are utilized faster and burned more quickly for energy, raising the body’s metabolism, while LCTs are utilized more slowly. Also, coconut oil is one of the richest sources of lauric acid. Its benefits have recently been touted to aid in destroying various bacteria and viruses such as listeria, giardia, herpes simplex virus-1, and maybe even yeast infections such as candida.

Wild Alaskan salmon oil is an excellent source of omega-3 fatty acids, which help reduce inflammation.

Probiotics are another important addition to the EPI diet, especially since most EPI dogs are or have been treated with antibiotics because of SIBO. Antibiotics wipe out not only bad bacteria, but also good bacteria. Probiotics help maintain good gut flora. One popular brand of probiotics that has been successfully used by EPI owners is Primal Defense, but there are many quality probiotics available.

Zinc deficiency is another consideration with EPI dogs. It is difficult to accurately measure zinc absorption. Human EPI patients often develop a zinc deficiency, and though no studies have confirmed this to be true of dogs with EPI, many vets suggest a zinc supplement for EPI dogs.

Vitamin E (tocopherol) levels may also be low in an EPI dog due to malabsorption. Vitamin E is a fat-soluble vitamin that is an antioxidant and helps in the formation of cell membranes, cell respiration, and with the metabolism of fats. Vitamin E deficiency may cause cell damage in the skeletal muscle, heart, testes, liver, and nerves; supplementation with vitamin E can help prevent these problems.

Other natural nutrient sources that are often included in an EPI diet are kelp, green tripe, slippery elm, and alfalfa.

Controlling EPI

Texas A&M and Clemson University are currently embarking on Phase II of an EPI research project to try to identify the genetic markers for the disease. “This disease is characterized by a complex pattern of inheritance,” says Dr. Keith E. Murphy, Professor and Chair of Genetics and Biochemistry at Clemson University in South Carolina. “Thus, we have been limited in how we can attack this in order to identify the gene or genes, that contribute to this horrible disease. However, we are encouraged by the success that we and others have had using SNP technology [unique DNA tests] to identify genetic markers associated with various traits and we will be employing this approach to EPI.”

It is important that this research continues. EPI is rapidly spreading across all breeds. It is no longer just a GSD disease, or a working dog disease. Dogs of all breeds, including crossbreeds, are being diagnosed with EPI. It is happening in family lines too often to be coincidence without a genetic component. Yet, not every family member or generation in affected lines has EPI. For now, until we can actually test for the genetic markers, the best possible control is to remove positively confirmed EPI dogs from breeding programs. Once genetic markers are identified in GSDs, the markers in other breeds will be more easily detected.

Although there are many success stories, there are also heart-wrenching tales of dogs who cannot thrive, families who cannot afford the treatment, and throughout it all, the painful suffering the dog endures unless successfully treated. EPI can no longer be a “hush-hush” disease. My hope is that this article will make a difference by helping raise awareness of EPI to the level of other major canine diseases.

Many EPI Dogs Flourish

Kara surfaced as a stray in a shelter and was subsequently turned over to the Long Island Shetland Sheepdog Rescue group. When they received her, they did not expect her to survive the night, she was so sick and emaciated. They guessed that she was probably one to two years old, but she weighed barely seven pounds – half her ideal weight.

Kara was lucky; she was diagnosed promptly with EPI. While in foster care for four months, Audrey Blake met Kara twice during training classes and the frail little dog with the outgoing personality captured her heart. Although she understood that Kara would need pancreatic enzymes for every meal and a special diet, Blake took Kara home. Today, Kara is known as “U-CD Twenty Four Karat Gold, UD, TDI, CGC (Kara), Rescue Sheltie,” and happily resides with Blake on Long Island, New York.

Sadly, Some Dogs Perish

At five years old, Wayde was taken in by German Shepherd Rescue of New England. Wayde was found to have EPI, an all-too-common problem with GSDs. He also had the secondary bacterial infection, SIBO. Even with enzymes added to his diet, Wayde continued to drop weight until he was only 54 pounds and seemed sad and listless all the time.

Wayde was in the kennel for many months. Finally, a couple who was familiar with EPI, Pamela and Peter Burghardt from Wilmot, New Hampshire, decided to foster Wayde. In their home, his whole demeanor changed; he became happy and gained more than

two pounds the first week. Wayde soon settled in with his foster family and became a sweet “Velcro” dog. He became best friends with his foster sister, another white GSD.

Sadly, Wayde was diagnosed with cancer a few weeks after going into foster care and passed away four months later. Despite the cancer, he had gained 14 pounds and was active and happy to the end.

Olesia Kennedy, a retired research analyst, and previously involved in Canine Search & Rescue, currently devotes her skills and time to EPI research. She resides with her husband and three Spanish Water Dogs in Georgetown, Indiana.