The October and November 2011 issues of Whole Dog Journal provided in-depth discussion of canine Addison’s and Cushing’s diseases. The following information should help clarify other questions that may arise about the diagnosis of canine adrenal disorders.

288

The relationships between adrenal cortisol and sex steroid production is complicated. In chronic illnesses, the body’s adrenal glands can become exhausted or fatigued. The adrenal glands may then respond by increasing the output of cortisol, and the intermediate and sex steroids. However, while the role of increased adrenal sex hormones, such as 17-hydroxyprogesterone and androstenedione, in promoting atypical Cushing’s disease is established, the role of increased estrogens, such as estradiol, in promoting SARDS (sudden acquired retinal degeneration syndrome) is scientifically unproven.

Part of this problem arises because of the documented differences between these sex steroid pathways in people and dogs. For example, in people, DHEA (dehydroxyepiandrosterone) activity is an important adrenal component in assessing body function and plays a role in obesity; it is frequently used as a supplement. By contrast, the normal levels of DHEA in dogs have not been established, and the potential benefit of DHEA supplements is unclear and may even be harmful.

Similarly, in people, estrogen assays include total estrogen as well as estrogen components, like beta-estradiol and estrone. In dogs, by contrast, the biologically important and regulatory estrogen is beta-estradiol. When the total estrogen concentration is measured in dog serum, it not only measures beta-estradiol but also detects all the metabolic breakdown products of this hormone, thereby leading to an apparent elevation in the total estrogen concentration, when it may not be truly functionally elevated. Thus, measuring total estrogen activity in dogs will likely give misleading results and lead to erroneous conclusions.

Likewise, measuring basal or resting cortisol activity in animals is misleading, because the cortisol is released from the adrenal gland continuously in pulsatile fashion over a 24-hour period. A single cortisol measurement is meaningless, regardless if it’s low, normal, or high, and is the reason that only dynamic tests of adrenal function (ACTH stimulation, LDDS suppression, and tests for the adrenal steroid intermediate hormones) accurately determine adrenal function.

-Adrenal exhaustion (also called adrenal fatigue) occurs when the adrenal gland (which produces cortisol in response to stress) has been over-stimulated and cannot function properly. Adrenal exhaustion is typically a transient condition and can result in impaired activity of the master glands such as the thyroid gland. Once the reason for the adrenal exhaustion is resolved, thyroid function should return to normal. In the meantime, however, nutritional supplements that offer thyroid support may be indicated and can be beneficial.

-Many physicians and veterinarians resist prescribing thyroid treatment in cases of adrenal exhaustion, because they are not technically treating a thyroid disorder, they are treating a temporary adrenal malfunction syndrome. To that, we say that if the patient shows marked improvement with thyroid hormone replacement and/or nutritional thyroid support, then why withhold appropriate and beneficial therapy? The fact remains that you are treating a thyroid responsive disease – and the patient is getting better !

Reliable Diagnostic Tests of Adrenal Function

Because of the complexity of the adrenal axis and its regulation by the body’s master glands, the importance of relying on assays performed only by an established commercial or university-based veterinary diagnostic reference laboratory is paramount. These diagnostic laboratories all participate in the national VLA Quality Assurance Program or the similar CAP Quality Assurance testing to document the accuracy of their laboratory procedures.

For comprehensive adrenal function testing, one of the most respected panels is obtained from the Clinical Endocrinology Service at the University of Tennessee, Knoxville (the late Dr. Jack Oliver’s program): vet.utk.edu/diagnostic/endocrinology.

W. Jean Dodds, DVM

Garden Grove, CA

I would like to bring readers’ attention to an excellent new book that dovetails nicely with my recent article (“Alpha, Schmalpha,” December 2011) about canine “dominance.”

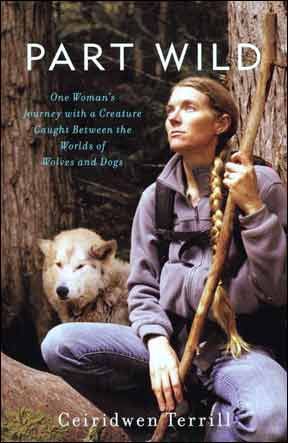

Part Wild: One Woman’s Journey with a Creature Caught Between the Worlds of Dogs and Wolves is a compelling and scientifically accurate recounting of author Ceiridwen Terrill’s challenging experiences as the naïve owner of a wolf-hybrid.

An engaging and articulate writer, Terrill sends two strong messages: if you are thinking of getting a wolf-hybrid as a pet, or worse, breeding them – don’t. Just don’t. And, if you believe the dominance/alpha nonsense spouted by many breeders (of hybrids and otherwise), some dog trainers, and an occasional television celebrity, please open your mind and learn more about the real science of behavior.

Terrill, an associate professor of environmental journalism and science writing at Concordia University in Portland, Oregon, weaves her science skillfully and painlessly throughout the book. I couldn’t put it down; I’ve recommended it on my Facebook page and all my training lists. If I had read it before writing “Alpha, Schmalpha” for WDJ, Terrill and Part Wild would have rated a very prominent mention in the article. Read it yourself. Then share it with any and all of your dog-owning friends who still buy into the flawed, archaic and obsolete dominance theory garbage and see if they don’t become converts.

Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, CDBC

Fairplay, MD