Ringworm is not a worm. Nor is it always ring-shaped. This misnomer of a term derived from an early inaccurate belief that the infection – which often causes a round, red, raised lesion on human skin – was caused by a worm. Unfortunately, this counterfactual name stuck and it continues to mislead to this day.

Ringworm, or dermatophytosis as it is scientifically called, is actually a fungal infection of the superficial layers of the skin, hair, and/or nails. While a diagnosis of ringworm might give you the heebie-jeebies, it rarely causes serious problems and it is both treatable and, to an extent, preventable. Identifying ringworm infections at an early stage can prevent transmission and limit contamination, so dog owners should become familiar with the common signs.

RISK FACTORS

Although ringworm fungi are everywhere, there are conditions that predispose dogs to infection. Dogs that are at a higher risk of contracting the disease include puppies, senior dogs, and dogs with a compromised immune system. Other risk factors include poor nutrition, high-stress environments (such as shelters), high-density housing of animals, skin with pre-existing trauma, and living in close contact with affected dogs.

Certain dogs may have lifestyles that increase their risk of ringworm exposure, such as hunting and working dogs (including the German Short-Haired Pointer, Fox Terrier, Labrador Retriever, Beagle, Jack Russell Terrier, German Shepherd Dog), possibly due to increased contact with contaminated soil. Yorkshire Terriers seem to be more susceptible as well and are often overrepresented in ringworm research.

The good news is that the occurrence of ringworm is relatively uncommon in healthy dogs. Even if a dog has been exposed, it does not mean that he will develop the disease.

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Dermatophytes invade keratinized structures found on skin, hair, and nails. In dogs, the head, ears, tail, and front paws are the most common sites of infection, although they may occur on any part of the body.

Ringworm infections tend to manifest as small, non-itchy asymmetrical patches of alopecia (hair loss), that spread outward on the skin. However, any combination of hair loss, papules, scales, crusts, redness, follicular plugging, hyperpigmentation, and changes in nail growth may be seen. The affected hair shafts are usually brittle and break near the skin surface, giving the lesion the appearance of having been shaved.

In the early stage, the center of the lesion often contains light-colored skin scales, giving it a powdery appearance, and the edges are generally reddish in color. Vesicles and pustules may also be seen. In later stages, the lesion may be covered by a crust and the edges of the lesion become swollen.

As these circular lesions enlarge, the central area may sometimes heal, leaving a circular lesion with central crusts or even hair regrowth. In some cases, there may be only one location of infection; in others, several patches may be present. As the fungus grows, the lesions may become irregularly shaped and spread, and individual lesions may merge to form large, irregular regional patches.

Severe infections may generalize (spread over the body); as a result, the appearance can resemble demodectic mange. Generalized cases usually occur in dogs who are immunosuppressed, especially those that have adrenal disorders or have been treated with corticosteroids. Occasionally ringworm infects a dog’s nails (as nails are comprised of keratin), causing them to become rough, brittle, and easily broken.

Fungi occur throughout the earth and have a critical role in most ecosystems. While the early fossil record for fungi is not extensive (their inherent structure does not lend to preservation), scientists recently reported a discovery in the Canadian arctic of a fossilized fungus estimated to have lived almost a billion years ago – which is even before the existence of plants! Suffice to say fungi have been around a really long time.

Early domestication of animals, such as cats and dogs, appears to have led to a later evolution of host-specific fungi. The group of fungi referred to as keratinophylic process keratin – a structural protein that forms hair, nails, feathers, horns, claws, hooves, calluses, and the outer layer of skin among vertebrates. This group of fungi is quite large, but only three genera – Microsporum, Trichophyton, and Epidermophyton – are known to cause disease in animals and humans.

The microscopic organisms responsible for ringworm infections belong to this keratinophylic group and are known as dermatophytes (derma = skin, phyton = plants). That’s why the infection caused by these agents is called dermatophytosis.

Some species of dermatophytes are species-specific, meaning they infect only one species; others can be transmitted between different species of animals, including humans. The three most common fungal species that cause ringworm in dogs are Microsporum canis, Microsporum gypseum, and Trichophyton mentagrophytes. Each of these are zoonotic (which means the infection is transmissible between animals and humans), but the rate of transmission is not known. M. canis is the etiologic agent of about 70% of the cases of canine ringworm; the remainder of the cases are from M. gypseum (20%) and T. mentagrophyte (10%).

INFECTION, TRANSMISSION, COMMUNICABILITY

Dogs who come into contact with the spores of the fungi may become infected if the dermatophytes infect growing hair or the keratin-rich outermost layer of the skin. Under most circumstances, dermatophytes live only in the dead cells of skin and hair and do not affect living cells or inflamed tissue.

As a dog’s immunity to the disease develops, further spread of infection usually ceases, but this process may take several weeks and infectious spores can still be dispersed. Therefore it is a good idea to treat cases of ringworm so that spread of the contagion can be limited and the healing process and time is improved.

While ringworm isn’t common in dogs, it is contagious and most cases of ringworm are spread by contact with infected animals or contaminated objects. Infected dogs shed spores into their environment, and spore-covered broken hairs are important sources for the spread of the disease. Thus, grooming tools, dog beds, toys, bowls, and home furnishings are prime objects for harboring the infectious spores. All of these should be disinfected if ringworm enters the picture. Ringworm spores are very hardy and can survive (i.e., be infective) in suitable environments for up to 12 to 20 months.

Ringworm fungi also resides in soil. Dogs who like to dig or roll around on the ground or stick their head in rodent holes may be exposed it regularly. While these favorite pastimes may expose them to the ringworm fungi, the likelihood of infection is not high; the establishment of infection depends on the fungal species and on the canine host factors. Susceptibility is increased when the dog has exposed skin surfaces (e.g., open wounds, cuts, scrapes, burns), as well as with high temperatures and humidity.

Note: Some dogs may be asymptomatic carriers; they carry dermatophytes on their body but do not develop any clinical signs of infection. These dogs are contagious and can contaminate the environment, which can be especially problematic in multi-animal environments.

A ringworm-infected dog is considered contagious and can transmit the disease to people or other pets including cats, pocket pets, cows, goats, pigs, and horses. Children (especially very young children), elderly people, and people with weakened immune systems or skin sensitivities may be more vulnerable to infection.

Because ringworm can be transmitted to humans, you should take appropriate steps to minimize exposure to the fungus while the dog is being treated. It is important to wear appropriate protection (especially gloves) and wash hands thoroughly after handling an infected dog. Environmental decontamination and control are critical in treatment.

Ringworm in humans generally responds well to treatment. Chances are, if a person hasn’t contracted it from their dog by the time it is diagnosed, it is unlikely that it will occur.

DIAGNOSIS

There is not a single test to diagnosis ringworm; obtaining an accurate diagnosis of ringworm requires utilizing a few complementary diagnostic tests to confirm the infection and to rule out several other skin conditions that can have a similar appearance.

* Wood’s lamp examination. A Wood’s lamp is a small hand-held ultraviolet lamp that emits light in a specific range of wavelengths. When they bind to hair shafts, the M.canis fungi produce a chemical reaction that fluoresces a striking, distinct, apple green under the Wood’s light in a darkened room. In many cases, using the Wood’s light uncovers additional sites of infection that were not visible to the eye.

That said, neither T. mentagrophytes nor M. gypseum fluoresce under a Wood’s lamp, so while the light is useful in establishing a tentative diagnosis, it cannot be used to exclude a ringworm infection.

* Microscopic examination. Since dermatophytes are visible under magnification, your veterinarian can take a sample of hair and skin scrapings for viewing under a microscope to see if any fungal spores are present. About 85% of ringworm infections, regardless of which type of fungus is present, can be confirmed this way.

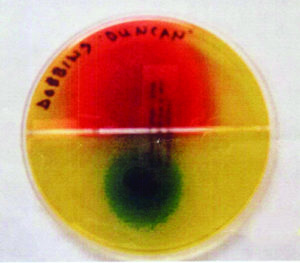

* Fungal culture. The most accurate test for diagnosing ringworm in dogs is by fungal culture of a sample of hair or skin cells. The sample is collected from the lesion(s) and placed in a special culture medium where it is monitored for fungal growth. A positive culture can sometimes be confirmed within a couple of days, but in some cases the fungal spores may be slow to grow; culture results can take up to four weeks. Therefore, a suspected sample cannot be deemed negative until four weeks have passed.

* PCR testing. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing is a newer diagnostic technique that can be performed on either tissue or hair samples. These samples are collected by your veterinarian and sent to a lab for processing. This test detects the DNA from any ringworm-causing fungi, providing results in just one to three days. A caveat: The test is highly sensitive and is not able to discern between true disease, contamination from surfaces, and non-viable fungal spores (which can’t cause disease but can be detected in a DNA test). This means that PCR testing is beneficial for making the initial diagnosis, but not helpful in determining whether the infection has resolved and treatment can be discontinued.

TREATMENT

In living hosts, dermatophytes usually remain in superficial tissues such as the skin, hair, and nails, living on the dead top layer of keratin protein. The lesions may be disfiguring and uncomfortable, especially when they are widespread.

But in rare cases, dermatophytes may go deeper into the body, invading subcutaneous tissues and other sites, especially in immunocompromised hosts.

Infections in healthy animals are usually self-limiting and may resolve within a few months without therapy.Treatment is recommended anyway, to accelerate recovery, reduce environmental shedding, and decrease the risk of transmission.

There is not a universal treatment plan for ringworm; your veterinarian will develop a plan based on the severity of the infection, how many pets are involved, whether there are children or other at-risk and susceptible individuals in the household, and how difficult it will be to disinfect your environment.

Effective therapy involves elimination of the infection in the dog through use of topical and/or systemic therapies, prevention of further dissemination, and disinfecting and removal of infective materials in the environment.

* Topical treatment. Topical therapy destroys the fungal spores on the lesion itself, thereby limiting environmental contamination and preventing transmission. Topically treated hairs are no longer infectious when they disperse into the environment. Topical therapy is especially important situations where infected dogs can’t be or aren’t confined.

For generalized dermatophytosis, a twice-weekly, whole-body treatment is recommended. Typical treatments include a lime sulfur (calcium polysulfide) dip (leave-on rinse), an enilconazole leave-on rinse (a broad spectrum antimycotic not available at this time in U.S.), or a miconazole-chlorhexidine rinse/shampoo (this antifungal and disinfectant combination work together to combat the disease).

For localized treatment, clotrimazole, miconazole, and enilconazole have been shown to be effective, but these are recommended as concurrent treatments, not as sole therapies. Topical treatment may be necessary for a period of several weeks to several months.

* Systemic therapy. Administration of an oral anti-fungal medication can be an important adjunct to topical therapy, especially for chronic or severe cases. Systemic antifungal therapy targets the active site of fungal infection and spread on the infected dog.

Effective systemic antifungal drugs include itraconazole, terbinafine, fluconazole ketoconazole, and griseofulvin. While griseofulvin has been the traditional antifungal drug for decades, its use is not as prevalent as it once was; newer medications appear to be safer and have less side effects.

Ketoconazole may cause liver pathology and is not recommended as the first-line of attack, but rather reserved for resistant cases.

Studies have determined that lufenuron (brand name Program) has not proven to be effective in either treating or preventing ringworm infection.

The drawbacks of systemic treatment are the relatively high cost of the drugs and the possibility of toxic side effects, which should be taken into consideration when developing a treatment plan. Dogs receiving any systemic antifungal should be closely monitored and all directions for administering the medications carefully followed.

When my 10-year old Border Collie Duncan developed a lesion on his muzzle at age 10, I was surprised to learn that he had contracted ringworm. He hadn’t been around any infected animals; I couldn’t figure out how he had contracted it – until my veterinarian explained that the fungus exists in the soil.

Trying to keep Duncan the Digger Dog from excavating was near impossible –

nor did I want to spoil his fun. But at least there was a good theory on how he had contracted it. In hindsight, in addition to being a senior dog, it was likely that he also had a compromised immune system, as we learned later when he developed other health concerns.

What began as a small hairless spot soon grew into a shiny quarter-sized lesion. When he was examined with the Wood’s light, the affected area lit up like a glowing orb in the night sky. Because ringworm is not all that common in dogs, my veterinarian called in all his staff to see my dog’s muzzle fluoresce. To confirm the diagnosis of M. canis infection, a sample of skin and hair were taken for culture.

While we waited for the results, we began topical treatment of clotrimazole 1% applied to the lesion two to three times a day and observed for response to this therapy. The good news is that he responded well to the localized topical treatment and neither I nor Daisy (my chemotherapy-immunocompromised Border Collie) contracted the infection. In about three months, the lesion was gone, the fur had grown back, and there was little to remind us of the fungal invasion.

ENVIRONMENT THERAPY

Diligent and thorough environmental decontamination is an imperative part of treatment. Without adequate attention to the environment, the infection may not resolve, it can spread, or even cause of reinfection.

If your pet has been diagnosed with ringworm, dermatophytes are now probably everywhere your dog has been. Infected hairs contain numerous microscopic fungal spores that can be shed into the environment and can survive for almost two years.

Because infection of other animals and humans can occur, either by direct contact with an infected dog or through contact with fungal spores, you now have to clean and disinfect everything your pet has come into contact with – and continue to do this throughout the treatment period. Yep, it’s a big bummer. But it is an essential part of treatment because affected dogs will continue to reinfect their environment until the infection has resolved completely.

How often you need to clean and disinfect depends on several factors, including the number of infected individuals, whether the treatment is topical, systemic, or both, and if there any at-risk individuals in the household. Your veterinarian can advise a tailored plan, but it is generally recommended that twice weekly cleaning includes mechanical removal of hair and washing and disinfection of target areas followed by disinfection.

As soon as possible following a diagnosis of ringworm, perform an initial thorough cleaning of your entire home, targeting your dog’s favorite spots. Mechanically remove hair, dander, and skin particles from all surfaces. Be aware that vacuuming alone does not decontaminate surfaces, but it does remove infective hair, so vacuum everywhere possible. After vacuuming, dispose of the vacuum bag outside of the home or disinfect the canister immediately.

Vacuum or use duct tape or lint rollers to remove hair from upholstered furniture. Carpet and rugs can be decontaminated by washing twice with a carpet shampooer with detergent or via hot water extraction. For hard surface floors, use commercial disposable cleaning cloths designed for dry mopping floors (such as Swiffer). Avoid brooms and mops as they are difficult to thoroughly clean and disinfect after use.

Dust with electrostatic cloths and dispose of immediately after use. Clean all washable surfaces with soap and water. Infective material is easily removed from the environment; if it can be washed, it can be decontaminated.

Any water temperature and any detergent are sufficient for decontaminating washable textiles (don’t forget to launder your dog’s bedding and toys); two washings on the longest wash cycle are recommended. Wash exposed items separately from non-exposed items and disinfect the appliances afterwards.

Daily removal of hair from the area where your dog is being confined is recommended.

Proper disinfection is a three-step process:

1. Mechanically remove all visible debris (hair and skin flakes); disinfectants are not effective in the presence of organic debris.

2. Wash the target item or surface with a detergent until the area is visibly clean, following with a rinse to remove the detergents, as cleansers some may inactivate disinfectants.

3. Apply a disinfectant to kill any residual spores. Readily available disinfectants include:

• Sodium hypochlorite (household bleach). Effective when used at concentrations ranging from 1:10 to 1:100 even with short contact time.

• Enilconazole. Available as a spray or environmental fogger. Relatively expensive. Has limited availability in some countries.

• Accelerated hydrogen peroxide (AHP). A newer broad-spectrum disinfectant that has gained widespread use. Available in concentrates and ready-to-use formulations.

• Rescue (Accel). Another effective broad-spectrum disinfectant. Available in a ready-to-use formula, concentrate, or wipes.

It’s often recommended that infected dogs be confined to one area of the home that is easy to clean. This needs to be balanced with preserving the mental and behavioral health of your dog, however, especially if he’s young or newly adopted. Confinement should be used with care and for the shortest time possible. Ringworm is curable; behavior problems can be lifelong.

RESOLUTION OF INFECTION

Many dogs will respond fairly quickly to treatment, often showing improvement within a week or two. Full treatment to clear the infection usually takes at least six to 10 weeks but can even last as long as three to four months.

Do not discontinue treatment as soon as your dog visually appears healed; dogs can still carry infective fungi even after signs appear to have completely resolved. Recurrent or lingering infections tend to be the result of treatment failure, either through inadequate duration of therapy or failure to properly decontaminate the environment.

Your veterinarian can monitor the healing progress (using a Wood’s light and/or fungal cultures) and use these results to determine when your dog is cured. Following your veterinarian’s recommendations is very important to ensuring a successful outcome and to prevent recurrence.

The good news is that almost all dogs recover completely with no long-term effects (hair loss is not permanent unless the follicle has been destroyed). Humans, on the other hand, may develop a permanent aversion to housecleaning!