Fact or Fiction: Can Dogs Have PTSD?

Should I Worry About My Dog Coughing?

As I listened to my dog cough the other night, I found myself shifting out of my logical veterinarian mindset and into my role as pet parent. Nobody likes it when their fur baby is not feeling 100%, including us veterinarians. When it does happen, I do try to remind myself that it is an opportunity to reacquaint myself with what it feels like to be on the other side of the exam table. Having a coughing dog is a great example of this because when there is a kennel-cough outbreak in the area, my veterinary hospital fields a lot of questions.

However, remember that kennel cough isn’t the only reason dogs cough. Heart disease and heartworms can also make a dog cough.

Pneumonia, which involves the lung more than the trachea/bronchi, can cause coughing but is more likely to be a softer moist cough than a honking cough. Dogs with pneumonia often feel sicker. They are more likely to be febrile, lethargic, and expend more respiratory effort to breathe.

Other causes of coughing include collapsing trachea, allergies, internal parasites, irritants, and neoplasia.

But, kennel cough does have a classic cough that sounds very much like a honking goose. The cough is loud, dry, and harsh. Concerned pet parents often describe the cough as sounding like their dog has something lodged in his throat. If your dog was totally fine and had something in his mouth right before sudden onset significant coughing/gagging began, then an object/food in her airway (or esophagus) is more of a possibility than if onset of coughing was more gradual.

So, what do you do when you suspect your dog has kennel cough?

- Don’t panic! Remember it is usually self-limiting and will clear on its own.

- Keep all the dogs in your household home (even if they haven’t started coughing) and don’t return them to activities until two weeks past cough resolution.

- Consult your veterinary team to determine if your pet needs to be seen for evaluation.

- Monitor all dogs but especially those that might be at higher risk for complications (very young, very old, immuno-compromised, underlying health issue) for signs of more severe illness.

- Rest your dog (keeping her calm and skipping high energy activities can help limit the coughing).

- Get a video of your dog coughing at home that you can share with your veterinary team if needed.

- If you are taking your dog to the veterinarian, notify the office of your arrival before bringing your pet inside the building, as they may have special instructions to limit contact with other pets in the waiting room.

What Is Kennel Cough?

Kennel cough is the common name for a highly contagious respiratory illness of dogs also known as infectious tracheobronchitis and canine infectious respiratory disease complex (CIRDC). Most commonly it presents as a dog that is still active but has a honking cough, often with a gag at the end of the coughing spell. If the gag is significant enough sometimes the dog will bring up phlegm or some of their most recent meal.

In otherwise healthy pets, most of the time it is an illness that is more annoying than life-threatening. When I say annoying, I mean both for the dog (because we all know coughing is not fun) and for the pet parent who empathizes with the dog and may experience some additional inconvenience such as cleaning up the phlegm/stomach contents that the dog gags up or disruption to plans.

Because kennel cough is highly contagious and spread through aerosol, direct contact, or contact with contaminated objects, other challenges for the pet parent can include having the illness go through all the dogs in the house one by one or having make short notice pet care arrangements because the dog can’t attend day care, grooming, or boarding facilities while contagious. Dogs should also not frequent dog parks, attend any dog competitions or go with their pet parents to visit households with other dogs.

Humans who are in contact with kennel-cough dogs should take care to wash hands thoroughly, change shoes, and clothes before being around other dogs so as not to spread the illness. There should be no sharing of toys or bowls although if in the same household there is probably already so much direct contact between family dogs that this may be a moot point.

As the name suggests, kennel cough most commonly spreads when a group of dogs are in common space together indoors such as in a boarding or daycare setting. Dog shows, dog performance events, or animal shelters can be another location of common spread because pets are coming together from many different areas and spending time in relative proximity to each other. It only takes a single dog that is infected with kennel cough (and possibly not even showing signs yet) to infect another dog.

The kennel cough vaccine usually starts with Bordetella bronchiseptica (bacteria) and often includes parainfluenza with or without adenovirus, but they are not the only infectious agents that cause these symptoms. If you have ever wondered why this vaccine is commonly given intranasally, it is because it allows not just for systemic antibodies but also antibodies that stay in the respiratory tract (secretory IgA) where they can act as a first line of defense. There is also a separate vaccine for two different strains of canine influenza (another virus that can often cause the same symptoms).

Why Is My Dog Coughing and Gagging?

“Why is my dog coughing from kennel cough when I got her vaccinated?” is one of the most common questions I get asked when I diagnose a dog with kennel cough. The reality is that kennel-cough symptoms can be caused by many different bacteria and viruses, and sometimes they can appear in combination. This is why a more recent medical term for kennel cough is CIRDC.

Kennel cough is most often diagnosed by physical exam and patient history. A common physical exam finding is increased tracheal sensitivity on palpation of the trachea. For cooperative dogs, this is a quick easy thing for your veterinarian to check as part of your dog’s exam because they can reproduce the coughing in the exam room to hear it for themselves.

Dogs can have tracheal sensitivity for other reasons so the veterinarian must consider the history and entire “picture” the dog presents but an absence of tracheal sensitivity typically moves kennel cough down my list. Most commonly the dog has a history of boarding, daycare, dog park (yes, it can spread outdoors), recent grooming, being in a shelter, or being exposed to another dog that has been one of these places. Sometime the infected dog isn’t coughing because she hasn’t started showing symptoms or she could have a subclinical case and appear asymptomatic.

Kennel Cough’s Tricky Diagnosis

It is possible to test for the offending infectious agent(s) but getting a conclusive diagnosis can be challenging. The samples usually need to be collected within the first couple of days of onset of symptoms. Many dogs don’t even see the veterinarian that early in their illness. Also, sample collection involves swabbing the pharynx (throat), nasal passage, and/or conjunctival area of the eye. We have probably all had enough COVID testing swabs done on ourselves by this point to understand that many dogs will object to this process and could requite mild sedation to collect samples.

Add on top of these factors that the test itself is not inexpensive, takes several days to return results, and may not produce a diagnosis. Reasons for not identifying an organism on the respiratory panel can include sample collection issues (timing, uncooperative patient) or a causative agent not severe enough/not studied enough to be included in the panel. All this is in the face of an illness that is generally self-limiting. This means a lot of pet parents will opt not to test. That doesn’t necessarily mean it is never worth testing, it just means one should have proper expectations.

In addition to the physical exam and patient history additional diagnostics such as X-rays, complete blood count, heartworm testing, and a fecal exam may help with diagnosing the cause of a cough.

Kennel Cough Requires Home Care

The good news is most dogs get better from kennel cough on their own with just a little time and TLC. Most of them don’t need antibiotics (remember, it is often viral, which antibiotics won’t help). Limiting high-energy activity can help because often the more excited the dog, the more they cough.

If the coughing is severe, your dog may need medication or treatment to help manage the cough either through suppressing the cough or decreasing the inflammation. The bad news is your dog needs to not go anywhere where she could infect other dogs for about two weeks AFTER symptoms resolve and the dog is off medication. It also means you should take appropriate precautions if you are in contact with any other dogs when you leave the house. As I mentioned earlier, this involves things like changing clothes/shoes and handwashing.

The Best Black Friday Deals for Dogs 2025

Join Whole Dog Journal

Already a member?

Click Here to Sign In | Forgot your password? | Activate Web AccessLaser Pointer Syndrome in Dogs

Oh, no, did you inadvertently create an OCD-like behavior in your dog by playing with laser pointers? Now that your dog is obsessed with that little red dot, are you wondering how you can undo what you did?

Laser pointer syndrome in dogs starts like an easy game to play with your dog. You can stay in a relaxed position while aiming a light pointer all over the place for your dog to chase. He gets exercise, has fun, and you are enjoying the scene. Sounds like a win-win, right? Nope.

Chasing a laser pointer is prey drive without the prey. There is no end to this game. Closure is incomplete and intense frustration often sets in. With laser pointers, the dog is left looking for the light everywhere. This can lead to other OCD type behaviors such as chasing sunbeams that are coming through your windows. I know of one dog who went wild when his owners got out aluminum foil because the sunlight was shining through the kitchen window and hit the foil.

Symptoms of laser pointer syndrome in dogs include:

- Chasing sunbeams/lights on the wall/reflections caused by various light sources

- Searching constantly for wherever the dog last saw the dot of the pointer

- Being so obsessed with chasing lights/shadows that nothing else matters

- Spinning in circles with frustration

How to Reverse Laser Pointer Syndrome in Dogs

Stop playing it! Immediately. Divert your dog’s attention with other games and activities. Learn to play a dog sport (scent work and Barn Hunt are great ideas for these dogs), get a flirt pole, carefully play tug, regular sniffing walks, do daily training with manners/handling/trick cues, give the dog appropriate toys and chews, and include plenty of positive interaction with the humans in your dog’s life. But do not EVER pick up the laser pointer again. You need to patiently engage your dog in other activities.

Learning how to effectively redirect your dog’s energies into a much more productive activity is the No. 1 priority. How to effectively redirect your dog depends on the individual dog, but active interests that fulfill your dog’s needs are important.

Note: If your dog has extreme laser pointer syndrome, you may need professional intervention. This is vital if your dog regularly ignores basic needs such as meals and other important self-care necessities. Your dog’s physical and mental survival depend on a quick intervention when things have reached this point. After veterinary intervention, schedule an appointment with a well-qualified rewards-based dog behavior consultant who can work hand in hand with your veterinarian to assure that your dog can learn coping mechanisms to redirect these obsessions.

It’s Prey Drive Without the Prey

Real prey drive with dogs has an end game. Whether with actual prey such as squirrels or other wildlife, the goal is the catch. Your dogs may not catch the squirrel, but the game has clear parameters, and the possibility is there. The dogs dream of the day that they complete that sequence. The same theory applies to other games of prey such as playing with a flirt pole or even playing catch. In these games, the completion is there. There is satisfaction, although there are some OCD concerns with some dogs to be aware of when capturing the prey is present. Properly done, the dog can let the game go when it ends for the moment.

Remember that there’s nothing wrong with getting assistance from a behavior professional to help with teaching your dog coping skills so that they are more able to effectively self-sooth will complete the puzzle.

IMHA in Dogs Is Often Deadly

Immune-mediated hemolytic anemia (IMHA) is a potentially deadly condition in dogs. You may also see it as autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) or autoimmune anemia. Regardless of what you call it, in this disease involves the destruction of red blood cells by your dog’s own immune system gone rogue.

Your dog’s red blood cells are responsible for transporting nutrients and oxygen to cells throughout the body, as well as picking up carbon dioxide, waste products including dead or damaged cells, and toxins. Your dog needs adequate red blood cells to live.

Normally, your dog’s body has a nice balance between new red blood cells being manufactured in the spleen and bone marrow and worn out or damaged cells being removed by the spleen. When the immune system destroys red blood cells faster than they are produced, your dog will become anemic.

What Causes IMHA in Dogs?

Unfortunately, the most common causes idiopathic, which means that the reason for the disease is never determined. American Cocker Spaniels have the highest risk of all breeds, which suggests a genetic predisposition.

Potential secondary causes abound, with tick-borne diseases at the head the list, followed by drug and vaccine reactions. Other potential causes include bee stings, snake bites, viruses, bacteria, and even cancer.

Signs of IMHA in Dogs

Any of the signs listed below justify a trip to the veterinary clinic. While IMHA can be treated, it has a high mortality rate. The sooner the treatment starts, the better the chance for a successful outcome.

Clinical signs you may notice include:

- Weakness

- Lethargy

- Pale gums

- Jaundice (ears, gums, groin)

- Small pinprick hemorrhages in the groin (called petechia)

- Nose bleeds

- Rapid breathing

- Racing heartbeat

Treatment for IMHA in Dogs

Some quick bloodwork will be done to verify that the problem is IMHA, and then treatment will start. At a minimum, most dogs will require intravenous (IV) fluids and some corticosteroids, and/or immunomodulating drugs. That generally means prednisone and a medication like cyclosporine. Expect your dog to spend some days in the hospital. Blood transfusions are frequently required, often more than one. In severe cases, stem cell therapy has been tried.

If an underlying cause is identified, treatment is aimed at clearing that up as well as treating the immediate symptoms. Sadly, even with rapid treatment, up to 50% to 70% of dogs will die. For those dogs who get released from the hospital, there is a relapse rate of about 15%. Most dogs will remain on at least some medications for life. Frequent rechecks are important to try and catch any relapse early on.

Can You Prevent IMHA in Dogs?

There is no real way to prevent IMHA other than regular preventive care, avoiding parasites like ticks, trying to avoid bees and snakes, and doing regular physical examinations to catch any cancers as soon as possible.

Know your dog’s family health history. For example, if littermates have had drug reactions, avoid those medications for your dog. Astute observation by you for any symptoms and responding right away increases your dog’s odds for a positive outcome.

Yes, Your Dog May Need Dental Braces

Join Whole Dog Journal

Already a member?

Click Here to Sign In | Forgot your password? | Activate Web AccessWhat Is a Sebaceous Cyst or Adenoma on a Dog?

It’s not uncommon to come across a lobulated pink or white growth on your dog’s skin, especially if he’s older. These bumps might be on his face, legs, or body. When you touch them, they may feel a bit oily and may even have a slight oily discharge.

These are likely sebaceous adenomas, which are benign tumors of the sebaceous (oil) glands of the skin. They range in size from tiny to about an inch in diameter.

These benign growths are most often found on middle-aged or senior dogs. Cocker Spaniels, Poodles, Miniature Schnauzers, and terrier breeds are most often affected. It’s wise to ask your veterinarian to look at any new growths, of course, but unless they look irritated, red, are bleeding, or are in an area that’s causing the dog to lick or chew at it, it can usually wait till your next visit.

Sebaceous Cysts in Dogs

Sebaceous cysts tend to be singular, smooth, and round. They are white or light pink, like sebaceous adenomas, they also may appear dark or pigmented. They may be found anywhere on the body, but the head is a common site. Some may even form along eyelids, where the eyelash follicles are. Schnauzers are often affected by sebaceous cysts.

These cysts occur near sebaceous glands in the skin, which are full of sebum, an oily substance that helps to lubricate and protect the skin. If a sebaceous gland becomes blocked, a cyst can form. The contained sebum becomes thicker and, if the cyst is opened, the contents are grayish and thick (like toothpaste).

Diagnosing Growths on a Dog

Diagnosis of both types of growth is generally done via observation. If your veterinarian has any concern, she may do a fine-needle aspiration to look at the cells under a microscope. Although rare, removal via biopsy is done with laboratory evaluation by a pathologist.

While both conditions may be unsightly, they usually do not present a serious health problem. If the cyst or adenoma ruptures, secondary bacterial skin infections may occur. Topical treatment such as cleaning with antibacterial solutions or wipes is generally all that is needed.

Removing Skin Bumps on a Dog

Most dogs ignore these cysts and adenomas unless one gets injured. At that point, the dog may lick or chew on the site. (It can be a challenge for groomers to avoid clipping these growths on dogs who have a lot of them.)

If your dog is chewing or licking at any sebaceous cysts or adenomas, you may choose to have them surgically removed. Depending on the size and location of the growth, this might be done by electrocautery, or it might require surgery. Recovery is rapid, but you will need to keep your dog from licking at the healing site.

Preventing Canine Skin Growths

There is no set way to prevent sebaceous cysts and adenomas. Bathing predisposed dogs with an anti-seborrhea shampoo may help, especially for cyst development. Keeping your dog clean and well-groomed may help. Diet has not been shown to be a factor.

Just remember that, while they may be unsightly, these growths are benign, which should be a relief to you!

What Is Discospondylitis in Dogs?

Discospondylitis in dogs occurs when a bacterial or fungal infection travels to the spine. The infection might just be at one point in the spine or could be at multiple spots at once. Note: Discospondylitis is different from spondylosis in dogs. While discospondylitis is an infection, spondylosis is a degenerative disorder of the bones in the spine.

How Discospondylitis Happens

Usually, the bacteria or fungi access the dog’s spinal discs via the bloodstream. An infection starts somewhere else in the body, such as in the mouth, on the skin, or in the urinary tract, and then the infectious agents hitch a ride in the blood. As blood circulates through the body, the bacteria or fungi may stop in the spinal discs and start up a new infection there.

Another cause of discospondylitis is a migrating foreign body, such as a grass awn or foxtail. These barbed awns can enter the body a variety of ways and then slowly move through tissue. The trail left behind is the perfect opportunity for infectious pathogens to follow along.

The third way that a dog can develop discospondylitis is after trauma to the back, such as a bite wound, getting hit by a car, or in rare cases secondary to back surgery.

Who’s at Risk?

Any dog can get discospondylitis, but large and giant breeds are the most often affected. Examples include the Great Dane, German Shepherd Dog, Boxer, Rottweiler, Doberman, and English Bulldog.

Chronic skin infections, having an immune system disorder, or being on immunosuppressive medications may predispose a dog to spinal infection.

What Discospondylitis in Dogs Looks Like

The symptoms of discospondylitis are non-specific, which means they can look like a variety of injuries and illnesses. Possible symptoms include:

- Pain

- Stiffness

- Reluctance to move

- Avoidance of jumping and/or stairs

- Flinching when touched

- Fever

- Poor appetite

- Weight loss

- Lethargy

If the infection has caused the disc to swell and put pressure on the spinal cord, the dog may also have neurological deficits such as stumbling or dragging one or more paws. Over time this can progress to limb weakness, muscle loss, and even paralysis.

Exact symptoms can also vary depending on the location of the infection site(s). Discospondylitis most commonly occurs in the thoracic and lumbar spine regions along the dog’s back.

Getting a Diagnosis

Diagnosing discospondylitis in dogs can take a while. The same symptoms can result from a variety of conditions, which means your vet needs to parse through all the potential causes.

X-rays are the simplest way to make a diagnosis. The catch is that it takes three to six weeks after symptoms start for bony changes to be visible on an X-ray. It may take a couple rounds of X-rays to see evidence of discospondylitis.

Advanced imaging such as myelography, CT scan, MRI, or bone scintigraphy can pick up signs of discospondylitis sooner. These procedures usually require a trip to a specialist.

Once discospondylitis is on your veterinarian’s radar, the next step is to identify the bacteria or fungus causing the infection. Your veterinarian may take blood and urine samples to culture, and will test for brucellosis. In some cases, a spinal tap to take a sample of cerebral spinal fluid may be necessary. This can be done under anesthesia by a specialist.

Rarely, the infected disc itself may be cultured. This requires surgery done by a specialist and is usually avoided because of how invasive it is.

Treatment

Treatment for discospondylitis often takes six to 12 months to clear the infection. Your dog will receive an antibiotic or antifungal medication depending on the type of infection, with the exact medication determined by the culture and sensitivity testing. Fungal infections are generally more difficult to eradicate than bacteria.

Your dog may also receive pain meds to keep him comfortable.

In some cases, it may be necessary to do surgery to debride damaged tissue, flush out the area, and relieve pressure on the spinal cord. This procedure should be done by a board-certified specialist.

Most dogs show improvement within two weeks of starting treatment. If your dog does not improve at that time, your vet will reassess and determine a new plan. Serial X-rays can be helpful to track healing of the bones in the spine over time.

Bacterial discospondylitis has the best prognosis. These dogs may relapse during the treatment period, but usually the infection can be fully treated.

Fungal discospondylitis has a more guarded prognosis. Many dogs respond to treatment, but others do not. Some dogs require lifelong medication to control symptoms and keep them comfortable.

Discospondylitis due to the bacterial infection brucellosis cannot be cured. This disease requires lifelong medication and careful management because it can be passed to humans and other dogs.

For all types of infection, severe neurological symptoms indicate a worse prognosis.

If your dog is diagnosed with discospondylitis, it is important to be diligent with medications for the full treatment period. Six to 12 months is a long time to give meds, but if it can get your dog back to his normal life, it is worth it!

How To Travel With Your Dog

Join Whole Dog Journal

Already a member?

Click Here to Sign In | Forgot your password? | Activate Web AccessStud Tail In Dogs

Stud tail in dogs is due to hyperplasia of the oil (sebaceous) glands on the dog’s tail. While intact males are most often affected, hence the name “stud tail,” it can occur in dogs of both sexes, including dogs who are spayed or neutered. There is speculation that this gland may produce some sex-related scents. This is based on the “violet gland” in foxes. Some dog breeders use that term as well, but no one seems to describe any associated odor as smelling like violets!

Causes of Stud Tail in Dogs

Most commonly, stud tail is caused by excess hormones, usually androgenic ones. This tail gland hyperplasia could be due to simple excess testosterone, adrenal gland hormones influenced by Cushing’s syndrome, or any tumor that causes hormone production. Other causes include:

- Hypothyroidism (low levels of the thyroid hormones)

- Seborrhea, although usually more areas than just the tail have blocked hair follicles and greasy skin

- Another skin disorder that influences the hair growth cycle

What Does Stud Tail in Dogs Look Like?

What you see is a funky area partway down your dog’s tail, close to the base. It may look swollen or simply greasy and discolored. There is usually some hair loss. Rarely, there will be an off odor. The area may be pigmented and feel bumpy.

It is more noticeable in dogs with short- or medium-length haircoats. Labrador Retrievers, Akitas, and German Shepherds seem to have a higher risk of this problem but that is anecdotal.

Complications of Stud Tail in Dogs

Most dogs blissfully ignore the area, but if your dog gets a secondary infection, you might notice him licking, chewing, or rubbing his tail. Inflamed, red skin, discharge, and even draining tracts may develop with an infection (usually bacterial).

Treatment of Stud Tail in Dogs

Your veterinarian will likely do a cytology and check for possible tumors or hormonal imbalances. If indicated, a needle aspirate or a punch biopsy to rule out any type of neoplasia may be done.

Mild cases without obvious infection generally respond to home care, such as cleaning the area with an anti-seborrhea shampoo or wipes with benzoyl peroxide or chlorhexidine. This cleaning may need to be done two or three times a week. Trimming the hairs around the area can make it easier to keep it clean.

If infection is present, antibiotic ointment or oral medications may be needed.

If your dog is intensely licking or chewing an Elizabethan collar can help speed healing by preventing the dog from reaching the area.

If your dog has an underlying condition such as Cushing’s disease or hypothyroidism, that problem needs to be treated.

Can You Prevent Stud Tail in Dogs?

Not really. Sometimes owners will elect for castration if their dog is intact. It will take a couple of weeks for all the signs to resolve after neutering as hormone levels drop, bit this may not clear the problem.

Fortunately, for most dogs, stud tail is a benign, cosmetic problem, which means keeping the area clean may be all that your dog needs.

Best Toys for Puppies

Chewing is a normal part of puppy development. Unlike humans, who have hands, curious puppies explore their surroundings with their mouths. They also begin teething around 3 months of age, where they lose their baby teeth and adult teeth begin to emerge, causing sore gums and a strong urge to chew. Providing appropriate toys for chewing and mental stimulation is essential for puppies to help soothe discomfort and prevent destructive chewing on household items like furniture legs, electrical cords, and shoes.

What Is a Good Teething Toy for Puppies?

A good teething toy should be safe, durable, and appropriately sized for your puppy’s breed and age. Soft but resilient materials, such as rubber, nylon, or silicone, are ideal for massaging sore gums without damaging new teeth. Textured surfaces such as small nubs and ridges can help maintain interest in the chews and allow the puppy to exhibit different chewing behaviors such as pulling and cobbing. Toys that can be chilled in the refrigerator are helpful for soothing gum inflammation and puzzle toys can help keep puppies stimulated and out of trouble.

Fortunately for this review, and unfortunately for my sanity, I had not one, but two puppies to test the following teething and puzzle toys out on! I have two young smooth-coated Collies: Merlin, who is now 1 year old, and Flick, who is 6 months old. These toys have been tested out for several months, and the verdict is in. We tested out six types of teething toys and three enrichment toys to help you pick the best option for your pups!

Overall Best Puppy Toy and Best Puppy Teething Toy:

Playology Young & Active Teething Bone

$19.99

Made in China

Scents: Beef, Chicken, Peanut Butter

This was a total puppy favorite. This toy is scented, a soft rubber, durable, and textured just right. The solid-cast nubs help sooth sore gums, and the texture and scent help keeps pups engaged. This toy touts a seven-times longer playtime due to the added scent, which I was skeptical about at first, but now I am sold on its benefits. This toy is easy to rinse off and clean, perfect for moderate to heavy chewers, and only shows some minor wear after four months!

This is the puppy’s favorite teething toy, and it is still their primary go-to months later! I will not bring a puppy home in the future without one of these in the house.

Best Puppy Tug Toy:

Nylabone Puppy Teeth ‘n Tug Toy

$13.19

Made in China

This toy was great for the puppies to play together with, and this is a toy they pick up to play with often. I do like it and would buy it again, however I wish I had sized up, as I got the toy for the size they were when they were much younger, and this is still a toy they like as much bigger dogs. This toy does not show any sign of wear, even after multiple vigorous tug and chew sessions.

Best Freezable Puppy Teething Toy:

$4.99

Made in China

This toy is designed to be wet and frozen for icy-relief! This is a great option for small dogs who are light chewers, but it is too small for larger breed puppies. This is a very soft toy, when it is not frozen, but my puppies did like all the little fabric tassles and were interested in chewing it.

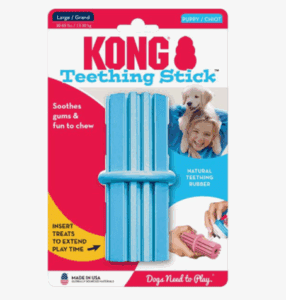

Best Puppy Teething Stick:

$13.99

Made in USA

This soft rubber toy has ridges that can be filled with treats, wet food, peanut butter, pumpkin, or yogurt for extra, and sometimes messy, fun! I liked freezing some sort of wet treat in the grooves to make it last longer and help sooth their sore mouths. My biggest complaint is that it can be challenging to clean. This was not the puppy’s first pick for chewing, unless it had food involved, but it is one they grab from time-to-time.

Best Puppy Toy for Power Chewer:

Benebone Tough Puppy Chew Multipack

$24.95 (4-pack)

Made in USA

We have lots of Benebones lying about the house and they have been a great, reliable chew for all my dogs, not just the puppies. However, they are very hard, and they can pose a risk for fractured teeth. They are also incredibly painful to step-on in the night—be warned. These toys are the only ones that I think would stand up against a power-chewer and the flavor in the chew keeps my dogs coming back for more!

Best Puppy Teething Toy for Enrichment:

$12.69

Made in China

This toy is stuffable and freezable to keep your pup entertained. I do find this toy much easier to clean compared to the KONG Teething Stick. Similar to the KONG, this was not a toy that I found the puppies grabbing often to chew on without added food for incentive, but it is one that is nice to have on hand for treat enrichment!

Best Puppy Snuffle Mat:

Nina Ottosson Snuffle Palz Bird

$15.99

Made in Cambodia

This snuffle mat is nice because it can be made more challenging by closing the Velcro arms. I love snuffle mats for puppies as it helps tire out their brains by making them problem-solve and use their noses to find the hidden food. This snuffle mat can be machine-washed, however, I do wish it was bigger. Be sure to supervise your puppy as chewing or ripping up the snuffle mat may be an attractive option, especially for frustrated pups!

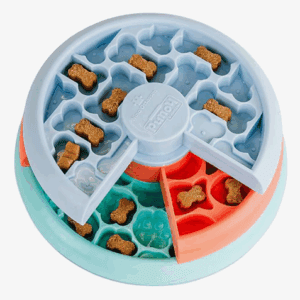

Best Puppy Puzzle Toy:

Outward Hound Puppy Lickin’ Layers Puzzle Feeder

$15.99

Made in Vietnam

This is a 3-in-1 lick mat, slow feeder, and puzzle feeder that features three layers of fun! Puppies have to spin, lick, and sniff through this slow-feeding puzzle. This toy is dishwasher safe and BPA free. While I absolutely love this toy/feeder combo, I would recommend sizing up to the normal size Lickin’ Layers bowl (for adult dogs) for larger breeds as the puppy version is quite small and can only hold about a half cup of food.

Best Slow-Feeding Puppy Toy:

$10.99

Made in China

This toy is fantastic for enrichment and slow feeding. There is a bit of a learning curve, but the ball can be adjusted to increase or decrease the flow of treats to make it more or less challenging. A word of warning, this is a LOUD toy, especially on hard floors and with kibble. If noise is an issue, I would recommend using it on a carpet and opting for a softer treat to fill it.

The right toys can make the many stages of puppyhood far more fun and comfortable for both puppies and their owners. Look for safe, appropriately sized options to encourage healthy chewing and structured play. Be sure to match the toy with your puppy’s chewing strength, check toys frequently for damage, and replace toys when worn. The expense of a replacement toy is always going to be less than a trip to the emergency vet! Hopefully, this review helps you find the perfect match for your puppy at home.

Can Dogs Have Tums?

Tums is an over-the-counter (OTC) human antacid composed of calcium carbonate. If your dog is battling stomach issues, your veterinarian may recommend an antacid for dogs to help with high levels of stomach acid, but it’s not likely to be Tums. Most commonly, your vet may prescribe an acid blocker such as famotidine (Pepcid) or omeprazole (Prilosec).

Tums for Dogs with Kidney Failure

For dogs with kidney failure, phosphorus buildup can be a serious side effect. Veterinarians usually prescribe phosphorus binders to deal with this, but Tums may be suggested as a low-cost alternative. The calcium in Tums helps to bind some of the excess phosphorus, which is then passed in the feces. This is not the ideal, however, and dosing directions need to be followed exactly. You should be in close contact with your veterinarian.

The use of Tums long-term without veterinary supervision can exacerbate kidney disease and/or cause an excess of calcium. Tums can also interfere with some other medications, generally making them less effective. You should always check with your veterinarian before trying any OTC medication for a dog with chronic health problems.

When to Consider Tums for Dogs

The most common use for Tums in dogs is for calcium supplementation for female dogs after giving birth (whelping). Tums should not be given during pregnancy or pre-whelping as it can lead to life-threatening hypocalcemia levels, problems during whelping, and problems during lactation if given pre-whelp.

Eclampsia, milk fever, or hypocalcemia can be seen in dams who are nursing. It is most common with large litters and with dams who were inappropriately supplemented with calcium while pregnant. Affected bitches may show muscle tremors and progress to seizures. Behavior changes may be the first subtle indication that something is wrong.

This is a medical emergency, usually requiring intravenous calcium. Post hospital care, bitches may be sent home with Tums as one of their sources of follow-up calcium supplementation. Directions should be followed exactly.

If Tums are suggested for calcium supplementation for your bitch post whelping, be sure to get an appropriate dose from your veterinarian. Check for the addition of flavorings like xylitol and for any dyes.

Remember, xylitol can be deadly to dogs, even in small amounts! Read the label ingredients. In addition, Tums preparations often have dyes added to make them appeal to people. Some dogs are sensitive to these food dyes to provide color.

Note: Tums is not approved for use in dogs but might be used off label for some dogs. Off label means the medication is not FDA approved for that use but generally regarded as safe for certain uses in pets under controlled conditions.