[Updated January 30, 2019]

Maybe this has happened to you: You’re reading or watching TV or at your computer, and your dog is lying on the carpet near you. You’re absorbed in what you are doing, but all of a sudden, you realize that your dog is licking or chewing himself, or scratching his ear with a hind paw. “Hey!” you say to your dog. “Stop that!” Your dog stops, looks at you, and wags his tail. You go back to doing what you were doing – and a few minutes later, you hear the tell-tale sounds of licking or chewing or scratching again.

Every dog does a certain amount of self-grooming to keep himself clean – and every dog owner should be aware of how much is normal, and how much is too much, because “too much” is often the first indication that a dog is having an allergy attack.

The most common sign of allergy in the dog is itching. When humans have an allergy attack, the most common symptoms are itchy, teary eyes; a runny nose; sneezing; and nasal congestion.

In contrast, allergic dogs itch all over. And so they scratch, chew, and lick themselves, trying to relieve that unrelenting itching sensation in their skin or paws or ears. The itch might keep them up at night (which might affect your own sleep, if their beds are in the same room as yours), make them cranky and out of sorts, and cause them to damage their skin.

In the throes of an acute allergy attack, dogs can lick, chew, or scratch a hole in themselves within just a few minutes of intense activity, allowing bacteria to gain access to several layers of skin and tissue and triggering a dandy infection. The itching in their paws may cause them to lick until sores develop between their toes or their paw pads develop ulcers. And the itching sensation in their ears can lead them to claw at their ears enough to damage and inflame the tissue, leading to infection and – if they shake their heads violently – cause blood vessels to burst in their ear flaps, leading to an excruciatingly painful, swollen ear. Untreated, ear hematomas (as they are called) can lead to tissue death and cause permanent disfigurement of the ear.

Over a lifetime, chronic allergies can leave dogs depleted and irritable, with low-level infections constantly breaking out on their skin, feet, and in their ears; worn front teeth (from chewing themselves); and smelly, sparse coats that neither protect them well from the elements nor invite much petting and affection from their owners. Chronic allergies can also deplete an owner’s time and financial resources – especially if the owner fails to take the most effective path to helping her dog.

Unfortunately, most dog owners rely solely on their veterinarians to take care of the problem with a shot or a prescription or a special food; they are unaware that they are in the best position to help their dog in a significant way. While veterinary diagnostic and treatment skills will be important in the battle, it’s the owner’s dedication to his dog, acute observation skills, and meticulous home care that will ultimately win the war against allergies.

Before discussing what can be done about allergies, let’s make sure you’re clear about what canine allergies are, and what they are not.

Canine Allergy Basics

In the simplest terms, allergy is the result of an immune system gone awry. When it’s functioning as it should, the immune system patrols the body, with various agents checking the identification (as it were) of every molecule in the body. It allows the body’s own molecules and harmless foreign substances to go about their business, but detects, recognizes, and attacks potentially harmful agents such as viruses and pathogenic bacteria.

When a dog develops an allergy, the immune system becomes hypersensitive and malfunctions. It may mistake benign agents (such as pollen or nutritious food) for harmful ones and sound the alarm, calling in all the body’s defenses in a misguided, one-sided battle that ultimately harms the body’s tissues or disrupts the body’s usual tasks. Alternately, the immune system may fail to recognize normal agents of the body itself, and start a biochemical war against those agents.

The three most common types of canine allergy are, in order of prevalence:

1. Flea bite hypersensitivity (known informally as “flea allergy”)

2. Atopy (also known as atopic disease or atopic dermatitis)

3. Food hypersensitivity (also called “food allergy”)

Let’s take a closer look at these three most common canine allergies.

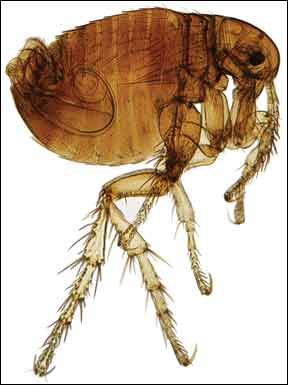

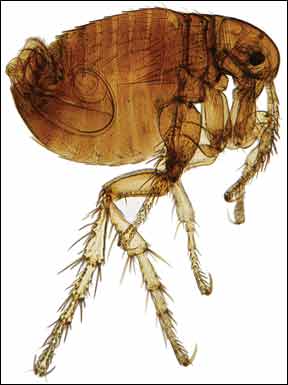

Flea Bite Hypersensitivity

Have you ever been bitten by a flea? If so, you know how irritating the bites can be. The flea injects its saliva into its bite during feeding to prevent clotting of its host’s blood. The flea’s saliva is what some dogs are allergic to – but even nonallergic dogs suffer skin irritation from flea saliva.

The site of a flea bite often develops a raised, red, itchy papule in allergic and nonallergic animals alike. The difference is, in a nonallergic animal, the number of papules and the amount of itching will be roughly congruent with the number of bites the dog received. (If a nonallergic dog was bitten just once or twice, he will experience itching and a bump on the skin in just those sites.)

Contrast this with an allergic dog, who may exhibit a severe reaction to just one or two flea bites, with generalized dermatitis and oozing papules emerging over his entire body. If you can’t find any fleas on your dog, or found just one flea after 10 minutes of using a flea comb on him, and yet he’s scratching himself raw all over, he’s very likely allergic to flea bites.

Like all allergies, flea bite hypersensitivity is a heritable trait; dogs from families with lots of allergies have a predisposition to develop allergies, too. It’s been estimated that about 40 percent of all dogs are hypersensitive to flea bites. In areas with cold winter temperatures and a resulting flea-free season, dogs who are allergic to flea bites will enjoy an itch-free period; in warmer climates, where fleas are a year-round problem, the flea-allergic dog’s suffering will be year-round as well.

Flea-bite hypersensitivity usually gets worse throughout the dog’s life. Each year, the signs of the allergy will start earlier and last longer in the “flea season,” and the itching will be more severe.

Atopy

Atopic disease (AD) in dogs is roughly analogous to hayfever in humans – except that instead of a runny nose and sneezing, a dog with this allergy will itch. Dogs with AD may be allergic to pollen, mold spores, dust, dust mite droppings, and other common environmental antigens. Dogs may be exposed to these allergens through breathing them in (inhalant transmission) or through transcutaneous exposure (through the skin). Estimates vary, but it’s generally accepted that 10 to 15 percent of all dogs have AD.

Dogs of any breed can suffer from atopy, but because the predisposition to the condition is heritable, the allergy is observed very commonly in dogs of certain breeds.

All dogs (like all humans) will experience an occasional itch. But dogs with AD will stop in the middle of eating or playing in order to scratch or chew themselves; it will be difficult to interrupt them or prevent them from scratching or chewing intently. The most common sites that atopic dogs focus on are the feet (which are licked or chewed); face (which they will rub against carpet or furniture); and ventral areas (tummy and groin are licked; “armpits” are scratched).

About 80 percent of atopic dogs also display flea bite hypersensitivity.

Food Hypersensitivity

A true allergy to foods is less common than many dog owners believe. Some experts estimate the prevalence of food allergy in dogs at 1 to 5 percent; other sources suggest a figure as high as 10 percent. However, almost half (43 percent, according to one study) of dogs who suffer from food allergy also exhibit other hypersensitivities, complicating the diagnostic picture.

Clinical signs of food allergy are extremely variable. The skin, gastrointestinal tract, respiratory tract, central nervous system, and any combination of these may be affected; the skin, however, is most frequently involved. Nonseasonal, generalized itchiness (pruritus) is the most common sign, with a distribution of itchiness on the dog’s body that is indistinguishable from that of atopy. About 10 to 15 percent of food-allergic dogs with dermatologic symptoms also suffer from gastrointestinal symptoms, including diarrhea, vomiting, gassiness, and cramping.

Food hypersensitivity can begin at any age, even late in a dog’s life. Allergies that start before a puppy is six months old are most likely caused by food.

Remember, “food allergy” and “food hypersensitivity” are the same thing; by definition, this condition is characterized by an abnormal immunological response to food. Don’t confuse those terms with “food intolerance,” which is an abnormal but non-immunological response to some foods. Dogs with food intolerance are far more likely to suffer digestive problems, such as vomiting, diarrhea, and gas.

Flea bites, environmental allergens, and food account for the vast majority of cases of canine allergy. But dogs can be hypersensitive to all sorts of other things, including the bites of flies, mosquitoes, ticks, and mites; drugs, medications, and nutritional supplements; various fungal and yeast species; internal parasites (such as ascarids, hookworms, tapeworms, whipworms, and heartworms); and even their own sex hormones (in intact animals).

Other Conditions That Can Cause Your Dog’s Itching

Allergies are not the only reason that dogs itch. In fact, to properly diagnose hypersensitivity, one of the first things a veterinarian needs to do is to rule out other potential causes of itching. “Allergies are a diagnosis of exclusion,” says Donna Spector, DVM, DACVIM, an internal medicine specialist with a consulting practice in Deerfield, Illinois. A dog’s medical history can sometimes help his vet identify the reason for the dog’s itching, but in other cases, the history may be lacking (such as with a shelter dog).

In other cases, a good history may exist, but the picture it presents is muddled. Complicating the diagnostic task is the fact that some causes of itching may actually be a secondary effect of the dog’s allergy. For example, a dog may be itchy because he has a yeast infection (an overgrowth of an organism commonly found on even healthy dogs) – or he may have developed a yeast infection as a result of licking and chewing (due to an allergy), which created the conditions in which the yeast organism thrives. It may take some time and tests for your vet to sort it all out. Here are some of the other conditions that can cause dogs to itch.

– Bacterial infection (pyoderma)

– Contact dermatitis from exposure to a caustic agent

– Drug reaction

– Fungal infection (including yeast)

– Hyperadrenocorticism (Cushing’s disease – causes a secondary infection)

– Hypothyroidism (causes a secondary infection)

– Immune-mediated disorders – Includes conditions such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

– Liver, pancreatic, or renal disease

– Parasitic infection – Includes internal parasites, as well as external parasites such as fleas, ticks, and mites. Three main types of mites are most problematic: Cheyletiella (“walking dandruff”); Demodex canis (which causes demodicosis, also known as red mange or demodectic mange); and Sarcoptes scabiei canis (which causes scabies, also known as sarcoptic mange).

Diagnosing Dog Allergies

Ideally, hypersensitivity to any substance would be confirmed by eliminating it from the animal or the animal’s environment, observing an improvement in the animal’s condition, and reintroducing it with a resulting resumption of signs of allergy. Then, “all” an owner would have to do is prevent his dog’s contact with that substance forever!

If you and your allergic dog lived in a bubble, your task would be a bit simpler; you could control the environment with precision and alter just one environmental variable at a time. But most dogs who are hypersensitive are often allergic to more than one type of allergen. Plus, the world is a dynamic, unpredictable place. Someone can casually hand your dog a treat he’s not supposed to have, or he can dive for and gobble an unidentifiable chunk of matter, and ruin weeks of a carefully constructed food elimination trial. A friend can stop by your house with her dog – and some fleas he just picked up at the beach – and the flea bites your dog received unbeknownst to you can result in a hypersensitive response that leads you to suspect your dog’s current food by mistake.

Even in the best of circumstances, identification of the substance or substances to which a dog is hypersensitive requires absolute diligence and daily observation from the dog’s owner, and an alert, interested veterinarian. And sometimes, the process can take years.

The first step, though, is finding a motivated veterinarian, and making an appointment for your itchy dog. There are many medical conditions that can cause itching, and the veterinarian will need to examine your dog, take a good history, and perhaps run some tests to rule out some of the nonimmunological causes of itching.

The history is particularly important. An astute veterinarian will be able to formulate likely theories about a dog’s allergic triggers based on the information you provide.

“You can find almost everything you need to know by taking a good history,” says Donna Spector, DVM, DACVIM, an internal medicine specialist with a consulting practice in Deerfield, Illinois. “There are good clues to be found in such facts as the environment the dog lives in, when the allergies started, the location on the body that is most affected, whether there is a seasonal component, the dog’s breed, and any medications he’s been given and what sort of response he had to those drugs. All these things will help pinpoint the most likely causes of the dog’s itching.”

Histories are most helpful, of course, when an owner has solid information to pass along. Dates of major itching episodes are perhaps the most helpful, because the date can often correlate to the prevalence of certain environmental allergens. The dog’s age and the season at the onset of the dog’s itching are significant. A full 75 percent of dogs with atopy show signs before they are three years of age. (However, the signs during the dog’s first year are often mild, and the owner may hardly recall the incident.) Also, curiously, dogs whose families move a lot when the dog is young may not show clinical signs of their allergy until they are older.

Highly inbred dogs whose relatives have a high prevalence of allergies may experience serious allergic episodes before they are six months old. Studies have shown that more than three-quarters of the dogs who are diagnosed with atopic allergies first showed signs in the spring, with the majority of the rest showing their first signs in winter.

The vet will want to know when your dog started itching (based on his self-scratching and chewing behaviors), how long the period of itchiness lasted, whether it changed in intensity, and what locations on his body he scratches the most. As eclectic as these facts might seem, each indicates something different about the dog’s condition. For example, “flea bite hypersensitivity” often starts on the dog’s back end and gradually spreads to more and more of his body, whereas a dog whose face seems to itch the most may have an autoimmune disease.

This is yet one more reason why we strongly suggest that all dog owners keep a journal for their dog’s health, or at a minimum, make notes on a calendar or planner about his health. Memory is highly fallible, but even a short note on a calendar (“March 1; Leroy licking his feet.”) can lead to a diagnosis, especially when one reviews the notes for a couple of years and finds a seasonal pattern in the dog’s symptoms. Note things such as when his diet is changed, when flea, tick, or heartworm preventives are administered, and of course, whenever you notice a significant change in his health, habits, or attitude. Your vet’s records will help fill in information about when (and why) your dog was seen at the veterinarian’s office, vaccinated, or given medications.

The vet should also conduct a very thorough and systematic physical examination. Every inch of the dog’s body should be inspected for lesions or redness, with special attention paid to the feet (especially between the toes) and inside the dog’s ears.

As part of the examination, the vet may use a small instrument to scrape cells from your dog’s skin. She will examine the samples under a microscope to look for mites, bacteria, and yeast.

After taking your dog’s history and conducting an exam, the veterinarian may want to run some tests. The ones she orders will depend on what her observations thus far lead her to suspect, or what she’d like to rule out. See “When It Comes to Allergy Tests, Some Flunk.”

If your vet suspects food allergy, or wants to test whether a food allergy might be a component of your dog’s itching, she might suggest a food elimination trial. The results can be rewarding, either confirming the presence of a food allergy or proving that your dog’s allergies are not related at all to his diet – but only if you are able to maintain strict control over every molecule that your dog eats during the duration of the test. See “Food Elimination Trial: A Valuable Tool.”

Some Dogs Show Negative on Allergy Tests

There are a few different types of tests available that purport to identify the allergens to which a dog is hypersensitive; some of them are helpful, and some are a waste of time and money. Since all of them are commonly referred to as “allergy tests,” few people know which ones are credible, and which ones are not. The following is a brief description of the types of tests available for allergy diagnosis.

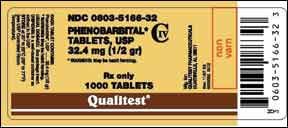

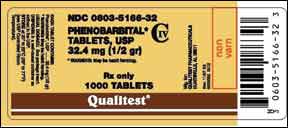

Blood (serologic) tests for antigen-induced antibodies

Two different methods (RAST and ELISA) are used for the most common commercial test products used by veterinarians, and the tests may be referred to by those names or by the name of the company whose test kit uses the methodology (such as Heska, Greer, or VARL). These tests are designed to detect antibodies that a dog has produced in response to specific environmental antigens. By identifying the antibodies, the tests were supposed to be able to deliver clues about the environmental substances that the dog’s immune system is treating as an “invader.”

Historically, the tests have been unreliable, with lots of false positive and false negative results, though the technology has improved over the years.

If the test results indicate “55 different things your dog is supposedly allergic to,” says Dr. Donna Spector, owner of SpectorDVM Consulting, in Deerfield, Illinois, it’s not particularly helpful, “and not particularly believable, when the results indicate your dog is allergic to something that he doesn’t even have significant exposure to.” However, she adds, if there is a really strong positive result, “not just one or two points above what they say is normal, but really strong results, you have something you can ask the owner about. ‘Does your pet have exposure to oak trees?’ If the owner says, ‘Oh yeah, they’re all over our property, we’re loaded with oak trees!’ then you’ve got something you can work with.” Or rather, something you can target with immunotherapy (allergy shots).

Dr. Spector has one suggestion for those considering paying for one of these tests: “It’s best to test right after the dog has gone through his worst allergy season, because his antibody levels will be the highest at that time, and you can get the best picture of what really bothers him the most. Sometimes a vet will run a blood test randomly, say, in the middle of winter, or ‘in preparation for the upcoming spring,’ and it is not as helpful.”

Skin (intradermal) tests for environmental allergens

In an intradermal test, tiny amounts of a number of suspected or likely local allergens are injected just under the dog’s skin. The location is shaved (the better to observe the reaction of the skin and underlying tissue) and marked (with a pen), so the response to each allergen can be recorded. Swelling and/or redness indicates the dog is allergic to the substance injected in that spot.

Identification of the substances to which a dog is allergic is helpful for two reasons. First, if the allergens that are problematic for a dog are known, the dog’s owner can try to prevent (as much as possible) the dog’s exposure to them. Second, testing identifies the allergens to be chosen for inclusion in customized allergy shots (also known as “immunotherapeutic injections”).

Most veterinary dermatologists feel these tests are much more reliable than blood tests for antibodies. It should be noted that the testing is more time-consuming and expensive, not to mention stressful for the dog, who must be observed very closely, several times, by a stranger!

Tests for food allergies

Both blood and skin tests for food allergies exist, but it’s difficult to find anyone (besides the companies that produce the tests) who feels the results are worth the paper they are printed on. It would be exciting and useful if it worked, but so far, the tests are a work in progress, with only an estimated 30 percent accuracy rate. Why would you bother – especially when you can conduct a food elimination trial that will deliver much more accurate information about your dog’s food allergies.

Allergy Treatments for Dogs

Once you and your veterinarian think you have a handle on what your dog is allergic to, it’s time to talk about treatment. Conventional western medicine acknowledges three major approaches for treating allergy:

1. Avoidance

2. Symptomatic therapy

3. Immunotherapy

Avoidance

Avoidance is brilliant. If your dog is allergic to something, you can just keep him away from it. No exposure = no reaction = no treatment! Simple!

Well, it’s simple when it comes to allergens that the dog might eat or a drug he might be given. But only rarely can one control a dog’s environment so assiduously as to entirely prevent exposure to airborne allergens such as pollen or dust.

My dog Rupert (long-deceased) was diagnosed as being allergic to redwood trees. At the time, we lived in a home that had a 150-foot redwood tree towering over it. Cutting down the tree was not an option. Poor Rupe! Fortunately, there were other options. I tried to reduce his exposure to the tree’s pollen and the dirt and dust under the tree (which I imagined was saturated with the tree’s pollen). I didn’t let him lie in the dirt under the tree; I bathed him (with a gentle dog shampoo) pretty much weekly; I washed his bedding weekly; I ripped out all the carpet in the house and kept the floors as clean as possible.

“Good housekeeping practices can help a lot,” agrees Dr. Spector. “I recommend washing the dog’s bedding frequently, at least once a week, in a hypoallergenic detergent. Wiping the dog with a damp cloth to remove airborne allergens, and brushing the haircoat regularly, helps distribute the natural oils and prevents mats that can irritate the skin. With some of the worst cases, I recommend using hypoallergenic pillowcases or mattress covers on the dog’s bed, so he can’t come into contact with any sort of fiber except the hypoallergenic ones. I might also suggest using a HEPA filter. And I’d think about keeping the dog inside on high-pollen days.”

Symptomatic Therapy

Symptomatic therapy means treating the dog’s symptoms. Through varying actions, anti-inflammatory drugs, antihistamines, and corticosteroids all counteract some of the inflammation summoned by the hypersensitive response. Of the three types of drugs, corticosteroids are the most effective at reducing inflammation, but they also pose higher risks to the dog if overused. See “Corticosteroids: Lifesaver or Killer?” next page.

Surprisingly, some antidepressant medications have proven to be helpful in reducing the urge of some allergic dogs to engage in self-mutilation.

Fatty acid supplements have emerged as safe and incredibly beneficial for allergic dogs. “Fatty acids have a really amazing anti-inflammatory effect on the skin,” says Dr. Spector. “Mildly allergic dogs respond best to them. In my opinion, severely allergic dogs should be on them as well; combined with an antihistamine, or some of the other treatment methods, you can get some great results. Fatty acids are incorporated right into the skin layers. They help improve the barrier of the skin, and help decrease the inflammatory cells in the skin.”

Dr. Spector uses a number of fatty acids supplements, but admits she most frequently reaches for the products made by Nordic Naturals.

Immunotherapy

Better known as “allergy shots,” immunotherapy consists of a course of injections of a saline solution; a tiny dose of the substance to which a patient is allergic is added to the solution. Generally, the shots are given once or twice a week for months, with the dose increased slightly each time until an effective dose is reached. The injections of the tiny dose helps the dog’s body become accustomed to the substance. In the best case scenario, after months of the shots, the dog no longer reacts to the substance when he encounters it in the environment.

In order to create immunotherapy customized for the patient, the veterinarian must conduct a “skin test” to determine all the substances to which the dog might be allergic. She first marks the site with a pen (containing hypoallergenic ink) and then injects a tiny bit of different allergens under the dog’s skin, with one allergen per marking. The vet must assiduously keep track of which allergens were injected in which spot and carefully observe the response of the skin to the injections. Swelling or redness in a square indicates the dog is allergic to the substance injected there. All of the allergens to which he reacted and that are likely to appear in the dog’s day to day environment are added to the immunotherapeutic injections, which are given for months or even years, depending on the patient’s response.

The majority of patients who receive immunotherapy improve; some actually completely recover from the hypersensitivity for life! However, the costs in terms of time and money are considerable. It’s worth the most to the owners of the dogs who had the most severe allergies and who responded very positively to the therapy. It may be judged as “not worth the cost” to owners who were unable to strictly comply with the required schedule of veterinary visits, whose dogs had mild allergies to begin with, and those whose dogs failed to respond strongly to the therapy.

Holistic Recommendations for Allergy Treatment

Most holistic veterinary practitioners recommend switching any itchy dog to a complete and balanced home-prepared diet containing “real foods.” This will decrease the dog’s exposure to unnecessary or complex chemicals and give his body the opportunity to utilize the higher-quality nutrients present in fresh foods. Whether the diet is cooked or raw, the increased nutrient quality and availability of fresh whole foods will improve the health of any dog who currently receives even the best dry or canned foods.

“Feeding fresh, unprocessed, organic foods provides more of the building blocks for a healthy immune system,” says Dr. Pesch. “Dogs who have allergies are more likely to be deficient in trace proteins and sugars (proteoglycans) that are used by the immune system. Deficiencies in these nutrients will increase the allergic response.” For her canine allergic patients, Dr. Pesch also recommends supplements such as colostrum, Ambrotose (a “glyconutritional dietary supplement ingredient consisting of a blend of monosaccharides, or sugar molecules”), and Standard Process supplements that contain glandular extracts.

Today, many veterinarians, holistic and conventional, recommend the use of probiotics, especially following any sort of antibiotic therapy. “I recommend a two-week course of probiotics following antibiotic use,” says Dr. Pesch. “It’s preferable to wait until after antibiotics are finished. If probiotics are given at the same time as antibiotics, they will be killed by the antibiotics and may reduce the efficacy of the antibiotics against the intended bacteria.”

Acupuncture can be used to help strengthen the immune system while reducing its overreactivity. “It’s not understood from a western perspective exactly how this is done, but acupuncture has been shown to increase white blood cell counts and circulation while at the same time stabilizing cell membranes and reducing histamine release,” says Dr. Pesch.

Dr. Pesch also recommends individually selected herbs to help reduce inflammation and irritation of the skin. “Many traditional Chinese herbal formulas can help reduce skin itching and inflammation without suppressing the immune system. They are usually not as strong as prednisone, but are in many cases sufficient. Additional herbs can be used to strengthen the immune system, reducing the intensity and frequency of subsequent allergy flare-ups.”

Homeopathy is another modality that can be extremely effective in allergy treatment. “I recommend classical homeopathy by a trained veterinarian,” says Dr. Pesch. “Classical homeopathy looks at the totality of symptoms for an individual to derive at a specific treatment for each unique case. The remedy mimics the disease in the body, stimulating the body’s defenses against the disease process.”

In my own experience, homeopathy is a hit-or-miss proposition. I’ve seen it work miracles on some dogs, and do absolutely nothing for others. Compared with many other medical interventions, homeopathy is inexpensive, poses little risk of serious side effects, and just may work. It’s worth a try, especially in cases where nothing else is working well.

Dr. Pesch expresses the holistic philosophy well. “Because of their ability to help improve immune system function without destroying the healthy balance of bacteria and fungi in the body, I regard the use of acupuncture and herbs or classical homeopathy, along with diet change and nutritional supplements, as the preferable treatment of allergies. This is true for allergies that affect the respiratory and digestive tracts as well as those that cause symptoms in the skin.”

Managing Your Dog’s Exposure

Dr. Spector is an internal medicine specialist and does not consider herself a “holistic practitioner.” But she shares the view of most holistic vets that it’s helpful to try to minimize the exposure of the allergic dog to chemical additives, toxins, and synthetic ingredients.

“I try to be cautious about overstimulating their immune systems in any way,” she says. “That goes for medication, too. Some antibiotics and sulfa drugs, for example, are more likely to stimulate the immune system. I would also choose to do titer tests before blanket vaccinating, to give only what is needed.”

It will also help to limit the dog’s exposure to common allergens – and not just the ones you know (through testing) he’s allergic to, says Dr. Spector. “People think, ‘My dog has an allergy to X, Y, and Z, and those are the things I have to watch out for.’ Unfortunately, most dogs with allergies will go on to develop new allergies throughout their lives, and anything they are exposed to will be on the list of possible allergens. It’s just the nature of the beast when you have an allergic predisposition.”

To that end, keep in mind that you are living with an allergy-susceptible companion, and keep your household exposure of dust, pollen, mites, and fleas to a minimum.

Greer, a maker of canine, feline, and human allergy tests and immunotherapy products, offers the following suggestions for the owners of allergic dogs. The recommendations are all very good:

– Dust and vacuum often, but not when the pet is present.

– Consider installing air conditioning, air filtration systems, and/or a vacuum with air filtration to avoid reintroducing allergens back into the pet’s environment.

– Use dehumidifiers to help control mold and mites.

– Limit the pet’s outdoor time during peak allergy seasons.

– Avoid going outside at dawn and dusk which can be times of high outdoor pollen.

– Rinse off your pets’ paws right after they’ve been outdoors.

Heska Corporation, another maker of allergy tests and immunotherapy products, adds these suggestions:

– Keep lawn grass cut short to reduce seed and pollen production.

– Keep pets off the lawn one to two hours after mowing or when the lawn is wet.

– Avoid letting pet put head out of car windows when traveling.

– Dry pet’s bedding in the dryer instead of outside.

– Frequently bathe pet using hypoallergenic shampoos, leave-in conditioners, and cool water rinses.

Speaking of “management,” it’s also important to manage your own expectation of your dog’s condition. Life with allergy is a marathon, not a sprint, and while new hypersensitivities can flare up at any time, resolution may also be just one more intervention away.

Nancy Kerns is Editor of WDJ. She’s owned one severely allergic dog, and still cares for an ancient allergic cat.