Download the Full August 2011 Issue PDF

New Lyme Disease Test for Dogs

Researchers at Cornell University’s Animal Health Diagnostic Center have developed a new test for Lyme disease in dogs. Available as of June 15, the Lyme multiplex assay is capable of distinguishing between infection and vaccination when vaccination history is available, and between early and chronic disease stages, from a single blood sample.

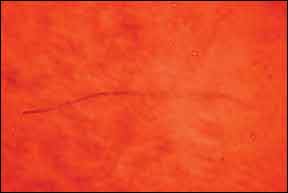

Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacteria that cause Lyme disease, migrate by way of the tissues to the joints, nervous system, and organs, causing fever, pain, lameness, and sometimes kidney failure (Lyme nephropathy). By the time these clinical signs show up, the infection may have been present 6 to 8 weeks or longer. Bacteria spirochetes can persist in the body for at least a year after clinical signs are gone, while high antibodies persist for at least 17 months. All of these factors make it difficult to distinguish between dogs whose clinical signs are caused by Lyme disease, and those who may been exposed in the past but have recovered from the disease.

Older tests for Lyme disease include whole cell enzyme-linked immunoassay (ELISA), indirect fluorescent antibody (IFA), Western blot, and C6 (SNAP® and ELISA). Whole cell ELISA and IFA tests cannot distinguish between antibodies induced from infection versus vaccination, while Western blot and C6 SNAP tests do not provide quantitative results. For this reason, two separate tests (ELISA plus Western blot) were required from Cornell’s lab for diagnosis and treatment.

The new Lyme disease canine multiplex assay combines the advantages of ELISA and Western blot in a single test. In addition, by identifying three different antibodies, it is the only test that has the capability of distinguishing between early versus chronic infections. Different antibodies point toward dogs who have been vaccinated for Lyme disease, those with early infections (up to 3 to 5 months), and those with chronic infections. The test can detect disease as early as 2 to 3 weeks after exposure, compared to 4 to 6 weeks for ELISA tests and 3 to 5 weeks for C6 tests.

Cornell says that its multiplex assay has increased sensitivity and specificity compared to other tests (resulting in fewer false negative and false positive results), and provides advanced information beyond any of the current Lyme testing methods, resulting in a better definition of the dog’s infection status. The fee for the test is $36, though the cost to you will include additional fees to your vet for drawing blood and shipping.

The Lyme Quant® C6 quantitative antibody test offered by IDEXX can also distinguish between infection and vaccination and provide quantitative results from a single sample. It might have even greater specificity (fewer false positives) than the new multiplex test, which could cross-react with at least one vaccine. Vaccination information must be provided along with samples submitted for testing to Cornell’s lab, so they can take that information into account when analyzing test results. That can be problematic for rescue dogs whose vaccination history is unknown. No such cross-reaction occurs with IDEXX’s SNAP® 3Dx®, 4Dx®, or Quant C6 tests, as no currently available Lyme vaccine stimulates a C6 antibody response.

While the IDEXX Quant C6 test cannot differentiate between early versus chronic infections, it can better monitor response to treatment, by comparing pre- and post-treatment results. A unique property of the C6 antibody is that levels decline sharply after treatment. Other tests measure antibodies that can persist at high levels long after treatment, making it difficult to determine whether the spirochetes are still present.

Doxycycline is used to treat Lyme disease at a recommended dosage of 10 milligrams per kilogram of body weight twice a day for four to six weeks. A controversy exists regarding treatment of dogs who test positive for Lyme but who show no signs of disease. Early research indicated that all but about 5 to 10 percent of dogs were able to fight off infection on their own, with no signs of the disease. A more recent study of 62 Beagles infected with Lyme, however, found that 39 dogs (63 percent) showed symptoms of the disease, and almost all had synovitis (inflammation of the joint lining) at necropsy. Because of the potential for Lyme disease to cause kidney failure, and because not all disease signs are noticeable (subclinical infection), treatment in all cases is the safest option.

– Mary Straus

For more information:

Cornell University College of Veterinary Medicine, Animal Health Diagnostic Center, (607) 253-3900; ahdc.vet.cornell.edu

Treating Your Dog’s Corns and Warts

Corns and plantar warts may be common on human feet, but they’re rare in dogs – unless the dog is a Greyhound. This breed is prone to corns.

Corns are keratin calluses on the front center paw pads, such as under the second toe bone, which lacks subcutaneous tissue or padding.

A common treatment for corns is their removal with a small curette or scalpel, followed by smoothing with a pumice stone and the application of salicylic acid pads or ointments. Roberta Mikkelsen of Pearl River, New York, hoped that hulling (surgical removal) would help her Greyhound, Chip, recover from his painful corns. “This is such a common problem in the breed,” she says, “that there is an online forum where people list the things that did or didn’t help. So far there isn’t a cure.” After Chip’s corn was removed, it grew back.

According to Dr. Bob Taylor of Animal Planet’s “Emergency Vets” program, an effective treatment is to cover the corn with a small piece of duct tape that does not cover healthy paw pad skin and replace it daily or every three to five days.

Canine warts cause a thickening of the skin and tend to occur on the back or underside of the paw. “Seed warts,” which contain black dots caused by broken blood vessels within the warts, are named for their resemblance to small black seeds. Warts are believed to be caused by the papillomavirus, but despite their viral connection, they are not contagious to dogs or humans.

Warts have so many anecdotal treatments that it’s impossible to list them here. Some are one-application wonders – a single drop of essential oil, a baking soda dressing, or an herbal salve makes a wart disappear for good. Other warts are so difficult to remove that they result in toe amputations.

Any wart or corn on a dog’s paw can be painful, resulting in lameness. Long walks on concrete and other hard surfaces worsen the severity of corns, so walking on softer surfaces as much as possible and wearing well-padded booties can make a positive difference. Thera-Paw boots and slippers were designed for dogs with corns or warts.

For information about other conditions that can affect your dog’s paws or nose, see “Identifying and Treating Skin Conditions Than Can Affect Your Dog.”

Identifying and Treating Skin Conditions that can Affect Your Dog

Yikes! What happened to Fido’s nose? And what’s wrong with Fluffy’s paw pads? The possibilities are many, and a surprising number of nose and paw pad problems are related. Because illnesses in this category often have similar or identical symptoms, a veterinarian’s diagnosis can be important. The following overview will help you identify, prevent, or treat these disorders.

Jump to:

Pigment problems on dogs’ noses

Digital hyperkeratosis

Collie nose

Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE)

Pemphigus complex

Other skin conditions

Pigment Problems

The most frequently asked questions about dogs’ noses concern color. Dogs have black or dark noses and paw pads because of melanin, a pigment that darkens skin. When melanin production slows or stops, the skin lightens uniformly or in patches.

Nasal hypopigmentation, also known as nasal depigmentation, is most commonly seen in the Golden Retriever, yellow Labrador Retriever, white German Shepherd, Poodle, Doberman Pinscher, Irish Setter, Pointer, Samoyed, Siberian Husky, Malamute, Afghan Hound, and Bernese Mountain Dog. Nose color is normal at birth but gradually fades to a light brown or whitish color.

Considered harmless, hypopigmentation does not make the nose more sun-sensitive and does not require treatment. However, this cosmetic imperfection matters to breeders because the loss of nose pigment is a conformation fault in the show ring.

Vitiligo (pronounced vit-ill-EYE-go) creates white spots of varying size and location on the skin when pigment cells, or melanocytes, are destroyed, preventing melanin production. Dogs with this immune system disorder develop white spots on the nasal planum (the hairless, leathery part of the nose), muzzle, and inner lining of the cheeks and lips, as well as patches of white hair and scattered white hairs through the coat. A skin biopsy confirms the diagnosis. Vitiligo is most associated with the German Shepherd Dog, Doberman Pinscher, Belgian Tervuren, and Rottweiler. Color loss is vitiligo’s only symptom.

Dudley nose, which is named for an English town known for animals with flesh-colored noses and light eyes, is a syndrome of unknown cause that may be a form of vitiligo. A puppy’s solid black nose may gradually fade to a solid chocolate brown or liver color, or, if the nose loses all of its pigment, pale pink. Some depigmented noses spontaneously regain their dark color while others remain pale.

Snow nose is a similar condition in which the nose’s dark pigment fades during winter months (without losing all of its color) and darkens again in spring and summer. No one knows what causes it, but one theory blames increased light exposure reflected on snow and another blames cold winter temperatures.

Color Treatment

There are no proven cures for the pigment problems mentioned here, but anecdotal recommendations abound. For example, supplementing with melatonin, the hormone associated with sleep, may help with seasonal changes. Vitiligo may respond to oral doses of folic acid (1 mg twice per day for an 80-pound dog) combined with vitamin C (500 mg twice daily) and injectable vitamin B12 (50 micrograms every 14 days). Some dog owners have reported success giving blueberry extract.

Juliette de Bairacli Levy’s natural rearing methods have been popular since the publication of her Complete Herbal Handbook for the Dog and Cat in 1955. “I introduced seaweed to the veterinary world when a student in the early ’30s,” she said. “It was scorned then, but now it is very popular worldwide.” She credited kelp and other sea vegetables with giving dark pigment to eyes, noses, and nails, stimulating hair growth, and developing strong bones.

It’s important not to overuse kelp; it’s rich in iodine, and too much iodine can suppress thyroid function. Levy’s NR Seaweed Mineral Food contains deep-sea kelp, nettle, and cleavers or uvi ursi, herbs that are associated with thyroid, skin, coat, and kidney health. The recommended daily dose is a pinch for small dogs, 1/8 to 1/4 teaspoon for medium-size dogs, and 1/2 teaspoon for large dogs. Kelp fed by itself should be limited to half these amounts.

Pink noses exposed to sunlight may burn or blister, and they are more at risk for the development of cancer. Sunscreen can protect pink noses; see the sunscreen recommendations under Collie nose (page 18). Another option is to have a dog’s pink nose tattooed with black ink, which shields the cells below, to give the nose permanent sun protection.

Nasodigital Hyperkeratosis

The term nasodigital refers to both nose and toes. A thickening of the outer layer of skin (hyperkeratosis) at the edges of the nose or paw pads can develop into painful cracks, fissures, erosions, and ulcers. The nasal planum, which is usually soft, shiny, and moist, becomes dry, hard, and rough, especially on the dorsum (top) of the nose.

Digital hyperkeratosis, which involves the entire surface of all paw pads, is most pronounced along the edges, as excess keratin (the skin’s tough, fibrous outer covering) is worn away on the weight-bearing surfaces in the center of the pads. The keratin may have a feathery appearance. Excess keratin in hard, cracked paw pads can make walking so painful that it causes lameness.

No one knows what causes this condition, which is associated with older dogs, particularly American Cocker Spaniels, English Springer Spaniels, Beagles, and Basset Hounds. Skin pigment is not affected, and the nose retains its natural cobblestone or pebbly appearance. Secondary bacterial or yeast infections in fissures can cause inflammation and increase discomfort. Other parts of the body are not affected.

Nasodigital hyperkeratosis has no specific diagnosis; it is determined by the exclusion of other conditions that might cause similar symptoms, such as discoid lupus erythematosus or pemphigus complex diseases. Veterinarians usually prescribe topical corticosteroids and antibiotics to control secondary inflammation and infection. Other treatments involve shaving or cutting away excess keratin, which must be done with care, along with the application of wet dressings and topical ointments. Bag Balm, a lanolin-based antiseptic ointment, is a popular treatment, as are Tretinoin Gel (a natural form of vitamin A that treats acne as well as keratosis and is sold by prescription), and petroleum jelly. Foot pads can be soaked in a solution of 50-percent propylene glycol.

Two products with numerous fans among breeders, owners, trainers, and veterinarians for the treatment of dry, cracked noses are Snout Soother, which contains unrefined shea nut butter, organic hempseed oil, kukui nut oil, sweet almond oil, jojoba, candelilla wax, rosemary extract, and natural vitamin E; and Nose Butter, a blend of shea butter, vitamin E oil, and essential oils.

Nasodigital hyperkeratosis is a lifelong condition. Treatment may start with soaking and topical treatments twice a day. Once improvement is seen, ongoing treatment once or twice a week or as the growths recur is required.

Milo, an 11-year-old English Shepherd belonging to Katie Palmer in Frederick, Maryland, has lived with this condition for five years. “It started as a rough spot on his nose and continued to get worse,” says Palmer. “If I leave it alone his nose cracks open and he yelps if he bumps it. Then it starts to slough off. Putting vitamin E oil on it makes it softer and not as cracked looking. Milo was fed kibble until one and a half years ago, when I got a Bernese Mountain Dog and put both of them on a raw diet. His nose still looks pretty bad but it’s better than before. I hoped the diet change might fix it, but so far it hasn’t gone away.”

In Denver, Colorado, Vanessa Graziano O’Grady’s 7-year-old yellow Labrador Retriever, Chisum, developed hyperkeratosis when he was a year and a half. His paw pads were treated with prednisone (a corticosteroid drug that suppresses inflammation), Accutane (a prescription form of vitamin A), and Kerasolv (an ointment containing salicylic acid that is no longer available).

“No luck with any of those,” says O’Grady. “Our vet completely trimmed all the excess off and it all grew back. Then our veterinary dermatologist introduced us to Bio Balm, a French ointment that moisturizes and helps heal noses and paw pads. It’s a blend of essential oils, soy oil, and palm oil. Within two weeks of using it nightly, the excess footpad skin started crumbling in my hands and falling off! We use it every night at bedtime on the edges of each pad and it keeps his pads smooth. The dermatologist was so stunned that she asked for pictures to share with colleagues.”

Chisum’s nose was affected, too, but despite two biopsies, his dermatologist couldn’t confirm a diagnosis. “We tried long courses of tetracycline and niacinamide but they didn’t do much, and neither did prednisone,” says O’Grady. “What seems to help the most is Protopic, a prescription ointment for eczema, which we apply once or twice per day. His nose is not perfect but it seems to be holding steady and hasn’t gotten worse.”

Collie Nose

Named for the breed most associated with its symptoms, Collie nose (nasal solar dermatitis) generates crusty lesions on the nose, lips, or eyelids. Its cause is a lack of pigment and inherited hypersensitivity to sunlight. Collie nose is usually classified as a type of discoid lupus erythematosus (see below) but is sometimes considered a separate illness.

Whatever its cause, nasal solar dermatitis tends to worsen in sunny climates and can result from other skin diseases or scarring. In advanced cases, the nose may become ulcerated, bleed easily, or develop skin cancer.

For Collie nose and similar disorders, sun avoidance is the most recommended treatment. Sunscreen can be applied to the noses of outdoor dogs within an hour of sun exposure and repeated frequently. Zinc oxide and other preparations containing zinc are not recommended, as excessive zinc is toxic to dogs. Sunscreens should be fragrance-free, non-staining, and contain UVA and UVB barriers similar to SPF 15 or SPF 30. Preparations made specifically for dogs include Doggles Pet Sunscreen, Epi-Pet Sun Protector, and Vet’s Best Sun Relief Spray. Dr. Mark Macina, a dermatologist at the Animal Medical Center of New York, recommends the human product Bullfrog SunBlock, and some caregivers report good results from Water Babies Stick Sunscreen. Both are widely sold.

Discoid Lupus Erythematosus (DLE)

Systemic lupus erythematosus is an autoimmune disease that affects the entire body. Discoid lupus erythematosus (DLE), a less severe form of the illness, affects only the face, causing depigmentation of the nose followed by open sores and crusts. Australian Shepherds, Brittanies, Collies, German Shepherds, German Shorthaired Pointers, Shetland Sheepdogs, Siberian Huskies, and crosses of those breeds may be predisposed to the disease.

There is no known cure for discoid lupus, which is the most common inflammatory disease of the nasal planum. In most cases, the nose becomes smooth and shiny rather than pebbly, it can lose pigment, and the skin of the nose becomes inflamed, crusty, atrophied, cracked, and ulcerated. DLE can affect the bridge of the nose, lip margins, the eye area, the inside of the ear flap, and in some cases the genitals. DLE can also cause inflammation of the third eyelid.

Because it’s aggravated by sunlight, discoid lupus erythematosus is usually worse in summer and is seen most often at high altitudes, where ultraviolet light exposure is highest. Veterinarians use oral and topical corticosteroid drugs to manage symptoms, and many recommend vitamin E as a supplement (400 to 800 IU given every 12 hours, two hours before or after meals) and essential fatty acids (both omega-3 and omega-6).

The combination of tetracycline (a broad-spectrum antibiotic) combined with niacinamide (a B-complex vitamin) has helped an estimated 50 to 70 percent of patients. More severe cases may require immunosuppressive drugs.

The application of sunscreen during periods of sun exposure is recommended (see Collie Nose, above, for more on sunscreen). Tattooing with permanent black ink can protect depigmented areas from sunlight, a procedure that is best done on young dogs with light pigment before lesions develop. Recently, reconstructive surgery has replaced ulcerated areas with normal skin.

Because this is an autoimmune condition, immune-enhancing supplements that strengthen or boost the immune system, such as echinacea, should be avoided, but immune-modulating supplements such as fish oil may help. Limiting vaccinations may also improve this condition, which is life-long despite periods of remission.

Barbara Gordon of Goffstown, New Hampshire, noticed crustiness around the nose of her German Shorthaired Pointer, Dagr (pronounced Dagger), during the summer of 2010. “We thought it might be a sunburn,” she says, “so we applied Bag Balm. Then in the fall it was still there, so we treated him for allergies with Benadryl. It started getting worse, with open sores and bleeding. The vet looked inside and couldn’t see anything, so she referred him for a rhinoscopy on February 1, 2011.”

Biopsies from the inside and outer edge of Dagr’s nose tested positive for discoid lupus erythematosus. The veterinarian recommended protecting Dagr’s nose with sunscreen and prescribed a daily treatment for the 55-pound dog of 500 mg niacin (vitamin B3), 1-1/2 teaspoons of the fish oil supplement Welactin, and 2 tablets doxycycline in the morning, followed by another 500 mg niacin and 1 doxycycline at night. To this regimen Gordon added Nupro, a supplement containing liver, kelp, and other nutrients, beginning with 1 ounce daily for a month and continuing with a maintenance dose of 1/2 ounce daily.

“I don’t know if stress aggravates it or not,” she says, “but the DLE flared up for a few days after we brought home a new puppy. He’s doing better now. His coat is awesome and his nose looks perfect.” Stress has been associated with the onset and flare-ups of lupus in people; it makes sense that the same would apply to dogs.

Pemphigus Foliaceus

One of several related skin disorders known as pemphigus complex, which develops when the body produces antibodies against the skin’s outer layer or epidermis, pemphigus foliaceus (PF) is the most common autoimmune disorder in dogs. It is also the most serious and has the highest fatality rate. Pemphigus foliaceus is both more common and more severe than discoid lupus.

The Akita, Chow Chow, Dachshund, Bearded Collie, Doberman Pinscher, Schipperke, Finnish Spitz, and Newfoundland are most commonly affected by pemphigus foliaceus, which usually develops on the head and feet before sometimes spreading to more of the body.

The initial symptom of PF is the formation of pustules (pus-filled blisters that look like pimples), which lead to severe crusting, scales, shallow ulcerations, and inflammation. Footpad overgrowth and cracking can result in lameness. A loss of pigment can change the color of the nose. Severe cases may produce fever and a loss of appetite. The blisters associated with pemphigus foliaceus are not always obvious, for they may rupture without being noticed. Chows and German Shepherds may be more prone to secondary bacterial infections.

Unfortunately, the treatment of pemphigus foliaceus isn’t always successful. Mild to moderate facial forms may be treated with tetracycline and niacinamide, similar to DLE, with about 30 percent of dogs responding. Prednisone is commonly prescribed for the life of the dog to control scabs and scaling, and it is often combined with antibiotics or immune-suppressing medications like azathioprine or chemotherapy drugs, all of which require careful monitoring.

Dogs on prednisone may drink more water than normal and can develop urinary incontinence. Because cortisone stimulates the appetite, they may experience metabolic changes, gain weight easily, and eventually develop diabetes. Secondary infections are common because open sores attract bacteria.

Promeris, a topical flea and tick control product, was recently linked to PF and will be removed from the market soon (see “Promeris Discontinued,” WDJ June 2011).

Julie Cassara of Rocklin, California, knows how complicated pemphigus can be. In 2008, Jack, her American Pit Bull Terrier/English Bulldog-mix, was 12 years old and in trouble. After being diagnosed with chronic renal failure and having a tooth extracted, Jack began limping. He soon developed crusty paw pad erosion, was diagnosed with pemphigus foliaceus, and was given prednisone, doxycycline, and daily foot baths in distilled white vinegar and water. “He reacted badly to the prednisone,” Cassara says. “His eyes had a glazed zombie look, he became extremely pushy with us as well as his sister, and he was relentless when it came to food.”

Three months later, the antifungal drug Flucanazole was added to his regimen. Because of Jack’s fragile health, Cassara worried about the effect of all these drugs on his organs, but their vet insisted this was the only way to treat PF.

Cassara soon transferred Jack’s care to Signe Beebe, DVM, a Sacramento veterinarian who co-wrote The Clinical Handbook of Chinese Veterinary Herbal Medicine and serves on the faculty of the Chi Institute of Chinese Medicine.

“Dr. Beebe stopped the doxycycline, weaned him off the prednisone, and started him on Chinese herbs and acupuncture,” says Cassara. “Jack never had another PF flare and he lived a wonderful life under Dr. Beebe’s care until the end of May 2010, a month before his 14th birthday, when his kidney failure progressed to the point where he lost interest in everything. We helped him to the bridge so he could pass away with the dignity he so deserved.”

Emmett, an Australian Shepherd belonging to Lisa Howard in Lewiston, Maine, was only 10 months old when he developed small scratches next to one of his nostrils. “It got all puffy,” she says, “and then the red puffiness moved to the top of his nose, grew larger, and developed blisters.” Punch biopsies, which remove small circles of skin, provided the pemphigus foliaceus diagnosis.

Prednisone cleared the condition, but symptoms returned when the dose was reduced, so it was increased again. Then Emmett swallowed some bone shards and developed bloody diarrhea, dehydration, anemia, elevated white blood cells, and a high liver count.

“The vet’s theory was that bone fragments damaged the lining of his prednisone-weakened intestines,” says Howard, “and that allowed bacteria into his bloodstream.”

Emmett spent two days in the hospital and after five days resumed his low dose of prednisone. That’s when the pemphigus erupted, covering his nose, eyelids, one ear, an elbow, both front legs, and the tip of his tail with swollen, red, blistery crusts and hair loss.

A canine dermatologist started Emmett on cyclosporine, a medication designed to suppress the immune system, and began weaning Emmett off the prednisone.

“He looks much better now,” says Howard. “All the blisters have gone except for those on his ear, which still have a way to go but are much improved. His hair has regrown and his energy is back to normal for a 19-month-old Aussie. Our goal is to get him down to cyclosporine only once a week.”

Other illnesses in the pemphigus complex are pemphigus vulgaris, the most severe form, which severely ulcerates the skin around the nose, mouth, anus, or vagina; pemphigus erythematosus, a milder form associated with Collies, Shetland Sheepdogs, and German Shepherds; and pemphigus vegetans, a rare and less-severe form that produces warty growths that may ulcerate. Pemphigus erythematosus so closely resembles discoid lupus erythematosus that a biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis.

Other Dog Skin Conditions

A number of other conditions can affect the nose and footpads, as well as other parts of the body.

Plastic dish dermatitis occurs when the plastic chemical p-benzylhydroquinone inhibits melanin synthesis, altering a dog’s nose and lip color. In addition to losing pigment, skin damaged by plastic can become irritated or inflamed. This dermatitis can affect any dog. Switching to glass, ceramic, or stainless steel bowls prevents this condition.

Vitamin A-responsive dermatosis is a rare disease seen primarily in Cocker Spaniels and reported in Labrador Retrievers, Miniature Schnauzers, and Shar-Pei. Rather than a nutritional deficiency, this appears to be a vitamin A deficiency in the skin caused by problems with the epidermis. Scaling, a dry coat, prominent pus-filled bumps, hair loss, crusts, and waxy ears are common symptoms. The diagnosis is confirmed by a positive response to vitamin A supplementation (usually in the range of 8,000 to 20,000 IU twice daily), which must be continued for life.

Zinc-responsive skin disease, which primarily affects 1- to 3-year-old Siberian Huskies and Alaskan Malamutes, is caused by a problem with zinc absorption. Zinc supplementation is required for these dogs for life. This disorder can also be caused by diets that are high in plant phytates or calcium, which bind zinc in the digestive tract, or by zinc-deficient commercial or home-prepared diets, or by diets that are over-supplemented with vitamins and minerals, especially calcium. Great Danes, Doberman Pinschers, Beagles, German Shorthaired Pointers, Labrador Retrievers, and Rhodesian Ridgebacks are susceptible to these nutritional problems, and their symptoms usually resolve within two to six weeks of dietary correction.

Commonly affected areas include mucocutaneous junctions (where smooth skin meets haired skin, such as around the eyes and mouth), as well as the chin, ears, foot pads, genitals, and pressure points. The coat is often dry and dull. Water soaks and anti-dandruff shampoos can loosen and remove the scaling and crusting.

Nasal keratosis associated with xeromycteria results from damage to (or the absence of) the nasal gland that keeps the nasal planum moist. Without it, the nose becomes dry and may be crusty at the tip. This condition can be linked to middle ear infections and may resolve with treatment. It can also be associated with dry eyes (keratoconjunctivitis sicca) and benefit from pilocarpine therapy. Topical moisturizers such as those recommended for nasal keratosis can help alleviate symptoms.

Nasal parakeratosis of Labrador Retrievers, a rare, hereditary condition, occurs in puppies (males more than females) with lesions on the nose or paw pads developing between six months and one year of age. Topical vitamin E, petrolatum (petroleum jelly), and propylene glycol help repair the lesions.

Proliferative arteritis is a rare, inherited vascular disease affecting the nasal philtrum, the vertical groove between a dog’s nostrils. Large dogs such as St. Bernards, Giant Schnauzers, and Newfoundlands between three and six years of age may be predisposed to this condition, which causes ulceration and hemorrhage. The V-shaped sore doesn’t usually become painful or infected, and symptoms may wax and wane. Proliferative arteritis, a lifelong condition, is often treated with glucocorticoids, tetracycline, niacinamide, and fish oil.

Familial paw pad hyperkeratosis, which is also rare, affects some lines of French Mastiffs and Irish Terriers and is also seen in Kerry Blue Terriers, Labrador Retrievers, Golden Retrievers, and mixed breeds. Lesions develop in very young puppies, before six months of age, and affect all of the paw pads dramatically. Thickened skin that resembles horns, fast-growing nails, fissures, splits in the skin, and secondary infections can lead to lameness. This condition may be a subgroup of ichthyosis, uncommon skin disorders that cause excessive dry surface scales due to abnormal epidermal metabolism or differentiation.

Hard pad disease, which develops two weeks after a dog contracts an active distemper infection, causes thick, hornlike callusing of the nose and paw pads. This symptom usually resolves when the dog recovers from distemper.

Leishmaniasis, a worldwide zoonotic disease that arrived recently in North America, causes lesions on paw pads and other body areas. Foxhounds are most associated with leishmaniasis, but other breeds are now affected. Nearly all infected dogs develop dry, hairless skin lesions that begin around the head or paw pads before spreading.

Allergies can affect a dog’s paw pads. Emma, Martha Sloane’s French Bulldog, was four years old and living in Upper Grandview, New York, when she began to itch all over. Sloane took Emma to veterinary homeopath Stacey Hershman, DVM, of Hastings-on-Hudson, New York. Emma’s feet were so red, itchy, and painful that she was barely able to walk.

In homeopathy, treatment depends on the patient’s individual symptoms, so there is no standard treatment for any of the conditions listed here. (See “How Homeopathy Works for Your Dog,” WDJ December 2007.) Emma was treated with nutrition and a series of homeopathic remedies, and within two months her feet – and the rest of her – were completely free from allergy symptoms.

Opportunistic infections, including bacterial, yeast, and fungal infections, are a problem whenever the skin cracks or is injured. The fungal condition aspergillosis can erode nasal passages, reshaping them so the dog develops chronic nasal discharge and in some cases bleeding. Malessezia, a form of yeast that commonly causes skin infections, can produce allergy symptoms, severe itching, hair loss, and crusty skin. Bacterial infections can produce skin lesions, pustules, hair loss, itching, and dried discharge. The treatment of secondary infections depends on their correct diagnosis.

What about garden-variety tender feet? Hunting dogs, sled dogs, and other active dogs can develop sore, cut, abraded, or injured paw pads. Blends of herbs, balsams, and natural waxes can help toughen the skin to help prevent minor injuries or protect pads from winter salt and chemicals, ice build-up, snowballing, summer sand irritation, hot pavement, and rough terrain. Popular remedies include Tuf-Foot and Musher’s Secret.

In the next issue, we’ll publish an article on one more condition that affects dogs’ toenails: Symmetrical Lupoid Onychodystrophy.

The Meanings Behind Different Dog Sounds

There are generally six types of sounds that dogs use in order to vocally communicate with humans or with other canines. Most noises dogs make indicate some form of frustration, like when a dog whines to go outside. But dogs will also vocalize pleasure – and happy dog noises don’t always sound too friendly! Here’s a rundown of what dog sounds might mean:

1. Barking

Why do dogs bark? Dogs bark for many reasons, including alert (there’s something out there!), alarm (there’s something bad out there) boredom, demand, fear, suspicion, distress, and pleasure (play). If you know how to tell between different kinds of dog barks, you can easily understand why your dog is so vocal in the first place! Believe it or not, dogs’ vocal communication methods aren’t just for annoying neighbors – they’re for telling you something important has happened!

The bark of a distressed dog, such as a dog who suffers from isolation or separation distress or anxiety, is high-pitched and repetitive; getting higher in pitch as the dog becomes more upset. Boredom barking tends to be more of a repetitive monotone. Alert bark is likely to be a sharp, staccato sound; alarm barking adds a note of intensity to the alert.

Demand barks are sharp and persistent, and directed at the human who could/should ostensibly provide whatever the dog demands. At least, the dog thinks so. Suspicious barks are usually low in tone, and slow, while fearful barking is often low but faster. Play barking just sounds . . . playful. If you have any doubt – look to see what the dog is doing. If he’s playing, it’s probably play barking.

2. Baying

Baying is deep-throated, prolonged barking, most often heard when a dog is in pursuit of prey, but also sometimes offered by a dog who is challenging an intruder. The scent hounds are notorious for their melodic baying voices. Some people interpret dog baying a long moaning sound.

3. Growling

Growls are most often a warning that serious aggression may ensue if you persist in whatever you’re doing, or what-ever is going on around him. Rather than taking offense at your dog’s growl, heed his warning, and figure out how to make him more comfortable with the situation.

If instead of a hostile growl, your dog is grumbling lowly, he may be perfectly happy! Dogs also growl in play. It’s common for a dog to growl while playing tug – and that’s perfectly appropriate as long as the rest of his body language says he’s playing. If there’s any doubt in your mind, take a break from play to let him calm down. Some dogs also growl in pleasure. Rottweilers are notorious for “grumbling” when being petted and playing, and absent any signs of stress, this is interpreted as a “feels good” happy dog noise.

4. Howling

Howling is often triggered by a high-pitched sound; many dogs howl at the sound of fire and police sirens. (Two of my own dogs howl when our donkey brays). Some dog owners have taught their dogs to howl on cue, such as the owner howling.

Howling is generally considered to be communication between pack members: perhaps to locate another pack member, or to call the pack for hunting. Some dogs howl when they are significantly distressed – again, a common symptom of isolation and separation distress.

5. Whimpering Sounds/Yelping

A whimper or a yelp is often an indication that a dog is in pain. This may happen when dogs play, if one dog bites the other dog too hard. The whimper or yelp is used to communicate the dog’s distress to a pack member (or human) when they are friendly. The other dog or human is expected to react positively to the communication. Whimpers can also indicate strong excitement such as when an owner returns at the end of a long workday. Excitement whimpering is often accompanied by licking, jumping, and barking. Dog whimpering is softer and less intense than whining. Puppy crying sounds are just little whimpers.

6. Whining

Dog whining sounds are high-pitched vocalizations, often produced nasally with the mouth closed. A dog may whine when it wants something, needs or wants to go outside, feels frustrated by leash restraint, is separated from a valued companion (human or otherwise), or just wants attention. It is usually an indication of some increased level of stress for the dog. Most often the dog crying sound is an exaggerated whine or whimper.

Speaking Words?

Some dogs are capable of replicating human speech sounds. When these sounds are selectively reinforced, dogs can appear to be speaking human words, sometimes even sentences. It is most likely that the dogs have no concept of the meaning behind the words they are “speaking” – although as we learn more about canine cognition, one can’t ever be too sure.

It’s interesting to note that one of the phrases most frequently taught to dogs by their owners is some version of, “I love you…” Youtube provides some entertaining footage of talking dogs, like this one.

Guide to Reading Canine Body Language

Despite conventional wisdom, a wagging tail doesn’t always mean a happy dog. The following abridged guide to canine communications will help you become a skilled translator. [ See also, “Learn to Read Your Dog’s Body Signals,” here.]

Remember that breed characteristics can complicate the message; the relaxed ears and tail of an Akita (prick-eared, tail curled over the back) look very different from the relaxed ears and tail of a Golden Retriever (drop-eared; long, low tail).

Also note that if body language vacillates back and forth it can indicate ambivalence or conflict, which may precede a choice toward aggression.

Tail

Tucked under: Submissive/appeasing, deferent, or fearful

Low and still: Calm, relaxed

Low to medium carriage, gently waving: Relaxed, friendly

Low to medium carriage, fast wag: Submissive/appeasing or happy, friendly

High carriage, still/vibrating or fast wag: Tension, arousal, excitement; could be play arousal or aggression arousal

Ears

Pinned back: Submissive/appeasing, deferent, or fearful

Back and relaxed: Calm, relaxed, friendly

Forward and relaxed: Aware, friendly

Pricked forward: Alert, excitement, arousal, assertive; could be play arousal or aggression arousal.

Eyes

Averted, no eye contact: Submissive/appeasing, deferent, or fearful; may be a subtle flick of the eyes, or may turn entire head away

Squinting, or eyes closed: Submissive/appeasing, happy greeting

Soft, direct eye contact: Calm, relaxed, friendly

Eyes open wide: Confident, assertive

Hard stare: Alert, excitement, arousal; could be play aroused in play or aroused in aggression

Mouth

Lips pulled back: Submissive/appeasing or fearful (may also be lifted in “submissive grin” or “aggressive grin”)

Licking lips, yawning: Stressed, fearful – or tired!

Lips relaxed: Calm, relaxed, friendly

Lips puckered forward, may be lifted (snarl): Assertive, threatening.

Hair

Piloerection: Also known as “raised hackles,” this is simply a sign of arousal. While it can indicate aggression, dogs may also show piloerection when they are fearful, uncertain, or engaged in excited play.

Body Posture

Behind vertical, lowered; hackles may be raised: Could be submissive and/or appeasing or fearful

Vertical, full height: Confident, relaxed

Ahead of vertical, standing tall; hackles may be raised: Assertive, alert, excitement, arousal; could be play arousal or aggressive arousal

Shoulders lowered, hindquarters elevated: A play bow is a clear invitation to play; the dog is sending a message that behavior that might otherwise look like aggression is intended in play.

READ: Do dog cry tears?

Guide to Stress Signals in Dogs

Anorexia

Stress causes the appetite to shut down. A dog who won’t eat moderate to high-value treats may just be distracted or simply not hungry, but refusal to eat is a common indicator of stress.

Appeasement/Deference Signals

Appeasement and deference aren’t always an indicator of stress. They are important everyday communication tools for keeping peace in social hierarchies, and are often presented in calm, stress-free interactions. They are offered in a social interaction to promote the tranquility of the group and the safety of the group’s members. When offered in conjunction with other behaviors, they can be an indicator of stress as well. Appeasement and deference signals include:

Slow movement: appeasing/deferent dog appears to be moving in slow-motion

Lip-licking: appeasing/deferent dog licks at the mouth of the higher ranking member of the social group

Sitting/lying down/exposing underside: appeasing/deferent dog lowers body posture, exposing vulnerable parts

Turning head away, averting eyes: appeasing/deferent dog avoids eye contact, exposes neck

Avoidance

Dog turns away; shuts down; evades handler’s touch and treats.

Brow Ridges

Furrows or muscle ridges in the dog’s forehead and around the eyes.

Difficulty Learning

Dogs are unable to learn well or easily when under significant stress.

Digestive Disturbances

Vomiting and diarrhea can be a sign of illness – or of stress; the digestive system reacts strongly to stress. Carsickness is often a stress reaction.

Displacement Behaviors

These are behaviors performed in an effort to resolve an internal stress conflict for the dog. They may be observed in a dog who is stressed and in isolation – for example a dog left alone in an exam room in a veterinary hospital – differentiating them from behaviors related to relationship.

Blinking: Eyes blink at a faster-than normal rate

Nose-Licking: Dog’s tongue flicks out once or multiple times

Chattering teeth

Scratching

Shaking off (as if wet, but dog is dry)

Yawning

Drooling

May be an indication of stress – or response to the presence of food, an indication of a mouth injury, or digestive distress.

Get more details on excessive dog drooling here.

Excessive Grooming

Dog may lick or chew paws, legs, flank, tail, and genital areas, even to the point of self-mutilation.

Hyperactivity

Frantic behavior, pacing, sometimes misinterpreted as ignoring, “fooling around,” or “blowing off” owner.

Immune System Disorders

Long-term stress weakens the immune system. Immune related problems can improve when overall levels of stress are reduced.

Lack of Attention/Focus

The brain has difficulty processing information when stressed.

Leaning/Clinging

The stressed dog seeks contact with human as reassurance.

Lowered Body Posture

“Slinking,” acting “guilty,” or “sneaky” (all misinterpretations of dog body language) can be indicators of stress.

Mouthing

Willingness to use mouth on human skin – can be puppy exploration or adult poor manners, but can also be an expression of stress, ranging from gentle nibbling (flea biting) to hard taking of treats, to painfully hard mouthing, snapping, or biting.

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorders

These include compulsive imaginary fly-snapping behavior, light- and shadow-chasing, tail-chasing, pica (eating nonfood objects), flank-sucking, self-mutilation, and more. While OCDs probably have a strong genetic component, the behavior itself is usually triggered by stress.

Panting

Rapid shallow or heavy breathing is normal if the dog is warm or has been exercising, otherwise can be stress-related. Stress may be external (environment) or internal (pain, other medical issues).

Stretching

To relax stress-related tension in muscles. May also occur as a non-stress behavior after sleeping or staying in one place for extended period.

Stiff Movement

Tension can cause a noticeable stiffness in leg, body, and tail movements.

Sweaty Paws

Damp footprints can be seen on floors, exam tables, rubber mats.

Trembling

May be due to stress – or cold.

Whining

High-pitched vocalization, irritating to most humans; an indication of stress. While some may interpret it as excitement, a dog who is excited to the point of whining is also stressed.

Yawning

Your dog may yawn because he’s tired – or as an appeasement signal or displacement behavior.

Learn to Read Your Dog’s Body Signals

How many times have I heard a dog owner say, “If only they could speak!” And how many times have I bitten back my first retort: “But they can speak! You’re just not listening!”

We humans are a verbal species. We long for our beloved canine companions to speak to us in words we can easily understand. While they have some capacity for vocal communication, they’ll never be able to deliver a soliloquy, or carry on long meaningful conversations with their humans. English is a second language for them. Their first is body talk – body language communication in which they generally say, quite clearly, exactly what they mean. Our problem, and as a result theirs, is that we humans tend to listen with our ears, rather than our eyes, and miss much of what they are saying.

Dogs do use some vocalizations in their daily communication with us and with each other (see “Canine Vocalizations,”). However, their body language is both more expressive and more prevalent – it’s continual! – so observing them in action is of more use than just listening to them.

There are those who have spent a lot of time trying to understand dog behavior and have become skilled at reading canine body language. They seem to interact naturally with dogs, using their own subtle body language to communicate, as much as or more than they use words. But time alone doesn’t grant this skill; there are also those who have spent a lot of time with dogs but are still woefully inept at properly interpreting the canine message.

Grasping Dog Vocabulary

The more you learn about your dog’s subtle body language communications the better you’ll be at reading them – and intervening appropriately, well before your dog is compelled to growl, snap, or bite. It’s important that you not focus on just one piece of the message. The various parts of your dog’s body work together to tell the complete story; unless you read them all and interpret them in context, you’ll miss important elements. Be especially aware of your dog’s tail, ears, eyes, mouth, hair, and body posture. For a basic vocabulary, see the “Canine Body Parts Dictionary“.

Because dog communication is a constant flow of information, it’s sometimes difficult to pick out small signals until you’ve become an educated observer. Start by studying photographs of dog body language, then watch videos that you can rewind and watch repeatedly, finally honing your skills on live dogs. Dog parks, doggie daycare centers, and training class playgroups are ideal places to practice your observation skills. Sarah Kalnajs’ DVD set, “The Language of Dogs,” is an excellent resource for body-language study.

Oblivious to Your Dog’s Stress?

Dogs tell us when they feel stressed. The more aware you are of your dog’s stress-related body language, the better you can help him out of situations that could otherwise escalate to inappropriate and dangerous behaviors. Many bites occur because owners fail to recognize and respond appropriately to their dogs’ stress signals. Even aside from aggression, there are multiple reasons why it’s important to pay attention to stress indicators:

-Stress is a universal underlying cause of aggression.

-Stress can have a negative impact on a dog’s health.

-Dogs learn poorly when stressed.

-Dogs respond poorly to cues when stressed.

-Negative classical conditioning can occur as a result of stress.

Note: the reasons to pay attention to stress also apply to all species with a central nervous system, including humans.

The smart, aware owner is always on the alert for signs that her dog is stressed, so she can alleviate tension when it occurs. Owners whose dogs are easily stressed often become hyper-vigilant, watching for tiny signs that presage more obvious stress-related behaviors, in order to forestall unpleasant reactions. If more owners were aware of these subtle signs of stress, fewer dogs would bite. That would be a very good thing.

A Canine Stress Dictionary lists some stress behaviors that are often overlooked. With each behavior the appropriate immediate course of action is to identify the stressor(s) and determine how to decrease the intensity of that stressful stimulus. In many cases you can accomplish this by increasing the distance between your dog and the stressor, be it a child, another dog, uniforms, men with beards, etc.

If possible, remove the stressor from your dog’s environment entirely. If he’s stressed by harsh verbal corrections, shock collars, and warthogs, those are all things you can simply remove from his existence (unless you live in Africa, in which case warthog removal might prove challenging).

For those stressors that can’t be eliminated, a long-term program of counter-conditioning and desensitization can change your dog’s association with a stressor from negative to positive, removing one more trigger for stress signals and possible aggression. Another strategy is to teach the dog a new operant (deliberate) response to the stressor – for example, teaching your dog that the sound of the doorbell means “Run to your crate to get a high value treat.” (See “Knock, Knock,” WDJ February 2010.)

Bitten “Without Warning”

The number of times a person has been bitten gives big clues as to his or her capacity to read, understand, and properly respond to canine communications. No sane person wants to be bitten by a dog. If someone has been on the receiving end of canine teeth numerous times, they aren’t paying attention to what the dogs are saying, or they aren’t responding appropriately.

Before they bite, dogs almost always give clear – albeit sometimes subtle – signals. The mythical “bite without warning” is truly a rare occurrence. Most of the time the human just wasn’t “listening.”

Happy Talk

We tend to focus on aggression signals because they are the most impressive and can predict danger. But any observant and aware dog owner knows that dogs offer a lot of happy communications as well. Behaviors such as jumping up, pawing, nudging, barking, and mouthing are often about happy excitement and attention-seeking.

Look for the signals that tell you your dog loves your new boyfriend, adores playing with the neighbor’s kids, enjoys riding in the car, is happy to romp with your brother’s dogs, and totally digs chasing the tennis ball. It’s important to pay attention to those communications as well so you know what makes him happy.

Your dog speaks to you all the time. Remember to listen with your eyes.

Orthopedic Equipment for Dogs that Increase Joint Support and Overall Mobility

In our March 2011 issue, we introduced you to a very small sampling of some of the neat “assistive equipment” options that are available to help our canine companions who have limited mobility or other physical issues. We received such a great response that we thought we’d share with you a few more finds that can help make life easier for you and your dog, particularly if he or she is aging or has orthopedic or neurologic issues.

288

Remember: the products mentioned here are only the tip of the iceberg. There are numerous companies making innovative assistive products; what we’re hoping to do here is to get you thinking about some of the possibilities!

No Slip Solutions

My husband and I purchased our home, in large part, to suit our dogs. What could be better than a one-level home with hard wood floors and no stairs to navigate? The single-level layout worked well as our dogs aged, but in their senior eyes, the hardwood floors have become a skating rink.

I dreaded the thought of buying carpet runners. They’d need a rug pad so they wouldn’t slip; they’d have to be vacuumed regularly; carpet is a breeding ground for fleas (especially here in the hot, humid south); and often, runners come with a dreadful chemical smell that takes a while to dissipate.

I was thrilled when I discovered a relatively inexpensive product called CarpetSaver, a lightweight, cotton blend, foam-backed terry runner that’s machine washable. I ordered a remnant roll and was able to cut the fabric easily with household scissors to varying lengths. Although this product will never make the cover of House Beautiful and is only available in four basic colors, I’ve been pleased with the quality, durability, and wash-ability of the product, along with the ease with which my elderly Bouvier, Jolie, now navigates through the house without missing a beat. I’ve gotten a return on my investment many times over! Suggested retail price is $20 and up; remnants and overstock sometimes available.

In some areas of our house, I’ve put down yoga mats for improved traction. They’re easy to keep clean; just pick up and shake out or vacuum. I recently learned that yoga matting is available in bulk rolls. A trainer friend lined the cargo area of her Honda Element with roll matting, making her English Mastiff very happy. The matting offers a great, grippy surface to walk on, but I’ve also found that guest dogs in our home gravitate to the mats as a comfy place to nap. Although I purchased Jolie’s yoga mats at a discount store for about $10 each, I recently found a 24″ x 104″ x ¼” roll of matting online for $125.

Front Limb Care

The signature product of DogLeggs Therapeutic & Rehabilitative Products is their Standard Adjustable DogLeggs. This product offers coverage, padding, and protection for elbow joints, and is regularly used to treat and prevent elbow hygromas – fluid-filled swellings at the point of one or both elbows, which can arise as the result of trauma or even from a dog lying for long periods of time on hard surfaces. In that case, over time, the point of the elbow bone traumatizes the soft tissue, causing inflammation and leading to the formation of a fluid-filled sac.

288

Standard Adjustable DogLeggs can also be used to help with a variety of other conditions, including elbow arthritis, decubital ulcers, pressure sores, and calluses, and a full length model for more coverage is available as well.

Consumers can measure their dogs themselves and order this product direct from the company; however, company spokesman John-Henry Gross believes that the best results are achieved when the client works with her dog’s veterinarian to measure and order the leggings. It’s also important to involve your veterinarian to be sure that what you’re looking at on your dog is a hygroma. Suggested retail: $108 (standard); $128 (full).

Hind-End Support

In our March issue, we talked about full body harnesses. In some cases, such as when a dog requires only hind-end assistance (i.e., post surgery), a full body harness might not be necessary. For those times, the Walkabout Back Harness (as seen on the facing page) is a great option. It’s made of a neoprene fabric with polypropylene webbing straps. It’s sturdy; has long, substantial handle straps (to save our backs!); and fits both male and female dogs.

To put the harness on, lay it flat on the floor and put the dog’s hind legs through two holes; the harness then wraps up over the dog’s back, closing with Velcro and buckles. I’ve had the chance to see the harness in action while being used to get a large dog (post-surgery, with two fractured hips) up and outside to eliminate, and it worked very well. While homemade works in some situations, I’ve seen firsthand that a product like this beats the old towel-under-the-belly, hands down. Suggested retail: $35 – $78.

Also in March, we mentioned one canine wheelchair, suggested by a veterinarian who specializes in canine rehab, as an example of the canine wheelchair-type products available. There are a number of other canine wheelchair makers, and each has products with unique features, benefits, and drawbacks. If your dog would benefit from a mobility cart, check out the offerings from the following companies to see what might work best for your dog, situation, and budget:

Doggon’ Wheels

888-7-DOGGON; doggon.com

Eddie’s Wheels

(888) 211-2700; eddieswheels.com

K9 Carts

(800) 578-6960; K9-carts.com

Healing Heat

Heat can offer our pets’ aching joints relief from pain, especially in cold, damp weather. The HipHug is a 100 percent cotton, rice-filled pad that you can heat in the microwave. What’s unique about the HipHug is that its cute bone shape is actually utilitarian: the way the pad is cut, it envelops and shapes to the dog’s hips and lower back nicely. The rice creates moist heat, easing joint pain and relaxing muscles.

288

As someone who spent this past winter getting up early to heat a pad to warm 14-year-old Jolie’s back and knees before her morning walk, I can attest that heat used properly can make a big difference in loosening up painful joints. Suggested retail: $13 – $25.

DogLeggs offers a similar product, the Buddy Bag, for hot or cold therapy.

How to Introduce New Equipment

Trainer and behaviorist Jean Donaldson posted a short video on YouTube of her Chow Chow, Buffy, gleefully accepting and wearing a stifle brace. In December 2010, then nine-year-old Buffy was diagnosed with a CCL (cranial cruciate ligament) tear. Donaldson chose to manage the injury conservatively, rather than subject Buffy to surgery, and opted for a stifle (knee) brace from OrthoPets. The brace helps prevent re-injury while the dog builds scar tissue and muscle around the injured knee.

In the video, Buffy was pretty happy to have Jean put on her brace. Donaldson spent time desensitizing Buffy to the brace before asking her to wear it. In fact, she first prepared Buffy for the casting procedure performed by Buffy’s veterinarian Anne Reed, DVM, which was required for fabrication of the brace. Dr. Reed was so impressed with Buffy’s cooperation during the casting that she asked Donaldson to write up a protocol for her to share with other brace clients. Donaldson graciously agreed to share it with us as well (see below).

After the casting, Donaldson prepared Buffy for the brace itself. Here’s how, in her words: “Show brace, then big pay-off (chicken). Touch leg with brace, then big pay-off. Hold brace against leg, then big pay-off. Add duration, paying off throughout. Add duration, pay off at end. Put brace on briefly, paying throughout. Put brace on, pay with intervals between installments. Put brace on, short walkies. Longer walkies.” She says it took only a few days for Buffy to willingly accept the brace but admits that the training she did for the casting likely sped up the process.

Buffy was rested for about eight weeks, then exposed to a gradual increase in length of walks and activity level, given supplements, and kept lean. Donaldson reports, “Buffy wears the brace for any activity where she might attempt a ‘sudden sprint.’ OrthoPets’ recommendation is for a dog to wear it for a maximum of eight hours a day. Buffy’s not a bouncing-off-the-walls kind of dog, so indoors she doesn’t wear it.” The plan is to gradually reduce the time Buffy wears the brace. See the video, “I’m Too Sexy for My Brace,” at tinyurl.com/buffybrace.

Lisa Rodier shares her home in Georgia with her husband and senior Bouvier, Jolie.

Allegations From a Former Merial Insider Regarding Heartgard’s Ineffectiveness

The lawsuit filed by Kari Blaho-Owens, PhD, against Merial, her former employer, contains a number of serious allegations regarding Heartgard’s decreased efficacy and Merial’s knowledge of the problem.

288

Merial denies the allegations, and has released the following statement regarding the lawsuit:

“Merial is aware of the lawsuit filed against the company by former employee, Kari Blaho-Owens. As a matter of company policy, we do not comment on the details of pending litigation or on employee-related issues. However, Merial believes we have acted appropriately and responsibly in all matters related to the allegations. Merial will vigorously defend the case and will assert strong defenses to the claims made. An earlier complaint filed by this former employee has already been dismissed by the United States Department of Labor.

“Merial stands by the effectiveness of our products. We are confident that the Heartgard® (ivermectin) brands are highly effective when used in accordance with their FDA-approved labels. Moreover, Merial strictly adheres to all regulations relating to the reporting of adverse events involving any Merial product.”

We may never know whether all the details alleged in the suit are true. It might take years in court – or it might be settled out of court. But the suit makes for fascinating reading. Here are some of the key points in the suit (to read the entire complaint, see tinyurl.com/44c6c44):

– In November 2004, the FDA’s Center for Veterinary Medicine sent Merial a letter, stating “there were numerous reports of ineffectiveness for heartworm prevention despite ‘Heartgard Plus’ being used according to the label directions.” In August 2005, FDA requested that Merial stop claiming 100% effectiveness for Heartgard Plus in preventing heartworm infestation.

– In 2005, Merial conducted an internal investigation regarding the increase in the number of reported cases of the lack of efficacy of Heartgard.

– When she reviewed the results of the 2005 investigation, Dr. Blaho-Owens asserts that “Merial had been aware of serious lack of efficacy adverse events reported regarding ‘Heartgard Plus’ since as early as 2002.”

– Merial claimed that its investigation showed that the increase in lack of effectiveness claims was the direct result of increases in sales, lack of owner compliance, and other factors – not a failure of the active ingredients in Heartgard products. Dr. Blaho-Owens claims she found numerous problems with the review, including “using ‘cherry-picked’ data, so as the persons evaluating the data would be led to support the conclusion sought by Merial.”

– In 2007, Dr. Blaho-Owens conducted further investigation in an effort to determine why “global monthly reports and the quarterly pharmacovigilance meetings demonstrated an obvious trend toward the increase in lack of effectiveness reports.” She was unable to find any reasonable explanation other than loss of efficacy of the Heartgard products.

– In 2008, Dr. Blaho-Owens’ supervisor “instructed her to stop her investigation.” One of the reasons given was that Merial had conducted a laboratory study showing “that heartworms had developed resistance to the ‘Heartgard Plus’ active ingredients, ivermectin and/or pyrantel; and that Merial was actively working to reformulate ‘Heartgard Plus’ to make it more effective by adding additional drugs to the combination product.”

– In September 2009, Dr. Blaho-Owens was notified that Merial was named in a class-action lawsuit regarding ‘Heartgard.’

– Dr. Blaho-Owens claims that on September 11, 2009, she was instructed to destroy a document that was likely relevant to the pending class-action lawsuit. Dr. Blaho-Owens also claims she was instructed to stop generating any new analysis of data regarding Heartgard despite her ongoing concerns relating to the lack of efficacy of Heartgard.

– Dr. Blaho-Owens says she reported her concerns to Merial’s legal counsel. Shortly thereafter, Dr. Blaho-Owens says she learned that the Heartgard class-action suit concerned Merial’s refusal to change its labeling as per FDA order.

– In conclusion, Dr. Blaho-Owens’ suit alleges that “Merial fraudulently promoted and sold ‘Heartgard’ as 100% effective despite its knowledge since at least 2002, that ‘Heartgard’ products were substantially less than 100% effective, in violation of FDA regulations.” The suit says, “Merial knew about the LOE (lack of efficacy) problem since at least 2002.”

Some Heartworm Preventative Medications Have Become Less Effective

[Updated January 10, 2019]

There is now ample evidence that at least one strain of heartworms has developed resistance to some of the market’s best-known preventives. In addition, there is evidence to suggest that one of the most popular heartworm preventives, Heartgard, has an efficacy rate of less than 100 percent.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s Center for Veterinary Medicine has sent at least one warning letter to Merial, the maker of Heartgard, asking the company to stop claiming 100 percent effectiveness for heartworm prevention. Given these developments, what should responsible dog owners do differently to better protect their dogs?

Photo by Isha Buis

The answer depends a bit on where you live and what you’ve already been doing to prevent heartworm infection.

Resistant Strains of Heartworm

Reports of dogs developing heartworm disease despite being given preventives year-round were dismissed for years as being due to “owner non-compliance,” but the outcry finally became too loud to ignore.

In August 2010, representatives of the American Heartworm Society (AHS), the Companion Animal Parasite Council (CAPC), and experts in the field of nematode resistance met in Atlanta for a “heartworm roundtable.” A joint statement released afterward announced, “This meeting was convened to discuss the implications of reports of lack of efficacy of macrocyclic lactones [preventive medications] against Dirofilaria immitis, the canine heartworm. Participants concluded that while we do not have a comprehensive picture of the scope or severity of the problem, we agree that there is a problem. There is evidence in some heartworm populations for genetic variations that are associated with decreased in vitro susceptibility to the macrocyclic lactones.”

Translation: investigators have verified that one strain of heartworms shows resistance to heartworm preventives in the lab.

Further, the statement offered a hint that the resistant strain is not yet present everywhere heartworms are found. “Most credible reports of lack of efficacy (LOE) that are not attributable to compliance failure are geographically limited at this time.” The statement did not identify the region, but investigations have centered on the Mississippi Delta.

Useful information has since emerged from a small study conducted by researchers at Auburn University’s College of Veterinary Medicine in Alabama. Four commercial heartworm preventive medications (Heartgard Plus, Interceptor, Revolution, and Advantage Multi) were tested on the resistant strain of heartworm. Forty dogs were infected with heartworm larvae. Thirty days later, the dogs were treated with one of the four preventives.

Four months after treatment, an average of 2.3 adult heartworms were found in seven of eight dogs in each of the first three groups; only Advantage Multi was found to be 100 percent effective. There was no significant difference in efficacy against the resistant strain between Heartgard Plus, Interceptor, and Revolution. Based on the number of adult worms found in the untreated control group, the efficacy rate for the other three products was determined to average 95.5 percent.

Say what? How can the efficacy rate be more than 95 percent, when 7 of 8 treated dogs (87.5 percent) were heartworm-positive? One might guess that “95 percent effective” means that 95 percent of dogs remained heartworm-free, but it actually means the treated dogs had 95 percent fewer adult worms than untreated dogs – a whole different can of worms!

What’s the Best Heartworm Preventive for Dogs?

Does this mean we should all switch to Advantage Multi, the only heartworm preventive found in this study to be effective against the resistant strain of heartworms? Well, the answer is not that simple.

The active ingredient in Advantage Multi is moxidectin (Advantage Multi also contains imidacloprid, the flea-killing ingredient in Advantage and K9 Advantix).

Moxidectin is the same ingredient used in ProHeart 6, an injectable heartworm preventive that reportedly caused problems for many dogs when it was first introduced. Due to the large number of adverse events reported, including many deaths, it was withdrawn from the market in 2004; it was reintroduced in 2008 with new warnings on the label.

Unlike ProHeart 6, a sustained-release injectable product used every six months, Advantage Multi is applied topically once a month. There’s a strong probability that the worst dangers of ProHeart 6 were related to the injectable, sustained-release method of application rather than to the drug itself. If there is an adverse reaction to moxidectin, it’s unlikely to be as intense or as long-lasting from a topical application as from an injected form, which continues to be released into the body for six months.

While every product has some adverse side effects, I have not heard any horror stories associated with Advantage Multi since it was introduced in the U.S. in 2007. Note that moxidectin remains in the system much longer than ivermectin (Heartgard), selamectin (Revolution), or milbemycin (Interceptor), so adverse effects can occur up to three weeks after application.

Dr. Byron Blagburn, one of the vets who participated in the Auburn University study, has hypothesized that moxidectin’s persistence in the body might account for its increased effectiveness against the resistant strain of heartworms.

NW SPCA

What about the other preventives? The study above found no significant differences in effectiveness between Heartgard, Interceptor, and Revolution against the resistant strain of heartworms; their efficacy rate ranged from 95.4 to 95.6 percent.

These findings correspond with anecdotal evidence observed by practitioners in the area where the resistant strain has been reported. Dr. Everett Mobley of Kennett Veterinary Clinic in Kennett, Missouri, is one of the veterinarians who drew attention to increasing failures of heartworm preventives that led to this discovery. He found reports of failure coming from the Mississippi River valley, starting about 100 miles south of St. Louis, and getting worse as one goes south.

“I saw roughly equal rates of lack of efficacy whether the dog was on Revolution, Heartgard, Interceptor, or Sentinel (the four preventives I was using at that time),” comments Dr. Mobley. He emphasizes that “I’m a simple general practitioner, detailing only my own clinical experiences and the impressions of those I have spoken with personally. I am by no means a specialist in parasitology or in pharmacology. My opinions are based on my experience with my cases.”

While he has not yet seen any failures with clients using Advantage Multi, he feels that the study referenced above is inconclusive due to its small size. Dr. Mobley says he has also seen a decrease in the number of heartworm-positive dogs taking other medications from 2009 to the present. He says, “while the big switchers to Advantage Multi feel that they see no product failures at all, our non-switchers have also seen a reduced failure rate in the last two years.”

This could be due to cooler and drier weather, at least in 2009. The American Heartworm Society’s (AHS) triennial survey for 2010 showed that “the pattern of heartworm incidence overall was similar to that of previous years.” While heartworm was found in all 50 states, the incidence map does show a decrease from the previous survey done in 2007, when the fallout from Hurricanes Katrina and Rita had far-reaching effects on mosquito vectors and heartworm transmission. The wet winter we’ve just had may well have a similar effect.

It makes sense for pet owners who live in the Mississippi valley to use Advantage Multi, as long as their dogs have no problems with it. For the rest of us, presumably not yet threatened by the resistant strain of heartworm, other products may be acceptable.

Heartworm Medication: Your Options

Interceptor, another heartworm preventive, may have one advantage over other products: its dosage of active ingredient (milbemycin oxime) is five times the minimum amount that has been determined to prevent heartworms; the higher dose is used to control intestinal parasites as well.

Because the level of medication is higher than was needed in the initial approvals for 100 percent efficacy, it’s possible that Interceptor may continue to be more effective against non-resistant strains of heartworms. Sentinel, which combines Interceptor with Program (lufenuron, a product that prevents fleas from reproducing), is another option with the same dosage of milbemycin oxime.

Revolution, a topical heartworm preventive whose active ingredient, selamectin, is also effective against fleas, ear mites, sarcoptic mange, and one type of tick, offers another alternative. You might use Revolution if you want to take advantage of any of these other properties, or if you prefer a topical treatment but do not want to use Advantage Multi.

Heartgard

Heartgard, like Interceptor and Revolution, demonstrated an efficacy rate of only about 95 percent in the Auburn University study on the preventive-resistant strain of heartworms. But there is evidence – some of it in active legal dispute – to suggest that Heartgard may exhibit only about 95 percent efficacy against all heartworms, not just the drug-resistant type.

In a letter sent in 2006 by the Food & Drug Administration (FDA) to Merial, the maker of Heartgard, the FDA warns, “In a letter dated August 24, 2005, we requested that you stop claiming 100% effectiveness for heartworm prevention. As you know, this request was based on the post-approval adverse drug event (ADE) reports we have received for lack of effectiveness for heartworm prevention. In a letter dated September 30, 2005, you agreed to immediately discontinue promotion and advertising 100% effectiveness for your heartworm prevention products.”

The allegation that Heartgard has only a 95 percent efficacy rate was leveled at Merial recently from another source – a “whistleblower” lawsuit filed by a former Merial employee.

Kari Blaho-Owens, PhD, global head of pharmacovigilance for Merial from 2006 to July 2010, alleged in documents filed in late May of this year that she “discovered that Merial had been aware of serious lack of efficacy adverse events reported regarding ‘Heartgard Plus’ since as early as 2002.” She believes that Merial terminated her employment because she refused to stop her investigation of the loss of efficacy of Heartgard and its related products. Dr. Blaho-Owens also asserts that she found a statistical analysis done by another Merial employee showing that Heartgard Plus was 95 percent effective. (That analysis would apply to all heartworms, not just the resistant strain.)

Merial denies the allegations. (See “Allegations From a Former Merial Insider“.)

Even if the allegations of a 95 percent efficacy rate were true, there are a couple of good reasons to continue to use Merial’s Heartgard, in our opinion. The first is the fact that Heartgard’s active ingredient (ivermectin) has some effect against adult heartworms – ones that developed while the dog was unprotected by any preventive or ones that developed despite the use of preventive.

One study we reviewed showed that Heartgard had nearly 100 percent efficacy in killing young adult heartworms when administered continuously for 31 months, and more than 50 percent efficacy after 18 months. Other recent studies on the use of a combination of pulsed doxycycline and weekly ivermectin resulted in a reduction of over 78 percent of adult worms after 36 weeks (see “Links for More Information,” below).

According to studies we’ve reviewed, selamectin (Revolution) has a lesser effect on adult heartworms, while neither milbemycin (Interceptor) nor moxidectin (Advantage Multi) have been found to have a significant effect against them. If your dog is infected with heartworms, it makes sense to use Heartgard prior to and during treatment with Immiticide, as it weakens the adult worms. It also makes sense to continue to use Heartgard for one year following treatment, to kill any heartworms that might mature from older larvae that neither Immiticide nor heartworm preventives can kill.

Iverhart and Tri-Heart Plus are generic equivalents to Heartgard that are manufactured by different companies. Efficacy and safety should be identical to Heartgard. Just be sure to purchase these products from reliable sites, preferably those that carry the Veterinary-Verified Internet Pharmacy Practice Sites seal of approval (Vet-VIPPS) and offer guarantees against product failures.

Heartworm Preventives: Use More, or More Often?

If you want to continue to use Heartgard for heartworm prevention, it also may be reasonable to use a higher dosage. The studies done for the initial approval of Heartgard showed that lower doses were less effective at eliminating heartworms than the dosage that was ultimately chosen for the label recommendation, which was the lowest dose found to be 100 percent effective. Increasing that dosage may well increase Heartgard’s effectiveness in preventing heartworm infection from non-resistant strains.