One of my worst dog-owner nightmares recently came true. Or I should say, almost came true. A raccoon attacked my dog, injuring her, but I was able to save her life by fighting off the raccoon myself! As bad as that experience was, I never imagined the problems I would have to deal with that have emerged since our initial suburban wildlife encounter.

288

My dog Ella is a Norwich Terrier, weighing just 11 pounds. I worried when I got a smaller dog that she would be more vulnerable to attack, whether from another dog, or from one of the critters (raccoons, opossums) that frequent my area because I live near a creek. While I rarely spot them, I know they’re around.

We went out to the backyard around 10:00 Saturday night, so Ella could go pee one last time before bed. I usually wait at the door, but this time, for whatever reason, I walked out with her. We were both on the grass when Ella started barking at something I couldn’t see on the fence. I figured it was one of the neighborhood cats – until it suddenly charged down the fence and in a flash attacked Ella, despite my being no more than two feet away and screaming at it to try to drive it away.

Ella tried to run for the house (she’s not a fighter, despite being a terrier) and they were on the deck in an instant, with the raccoon trying to attack her underside. I knew that if I didn’t do something, the raccoon, which was two or three times her size, would almost certainly kill my dog. My first thought was to pick Ella up, but I was afraid the raccoon would just keep attacking, and would then get me as well. In desperation, I went for the raccoon instead.

I grabbed its tail and pulled back and up, lifting it off the ground. It had hold of Ella’s head at that point and didn’t want to let go, but I kept pulling and it finally released her, or she managed to pull away. She was able to run into the house, while I spun around twice in a circle, swinging the raccoon by its tail. I launched it as far from me as I could (maybe six feet). When it landed, it turned right back toward me, despite the fact that I was screaming at it like a banshee. After what seemed like a long moment, it finally turned away and left.

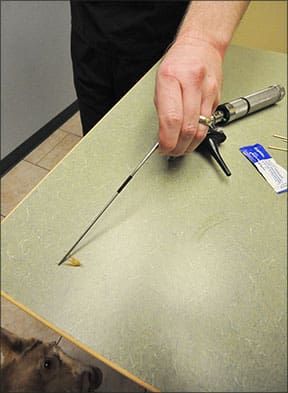

I hurried into the house to find Ella with blood on her face and favoring one of her front legs. I drove her to the emergency vet immediately, and it turned out she had several puncture wounds on her muzzle and front legs, but nothing worse. They sedated her, cleaned the wounds, gave her pain medication and antibiotics, and sent us home with more of the same.

She was very sore Sunday morning, hardly able to put weight on her right front leg, and her wounds had already stopped draining, which was not good; the vet wanted them to stay open so that any infection would drain out rather than create an abscess, in which case a drain would have to be put in. I applied warm compresses for 10 minutes four times that day, following the vet’s instructions. By evening, Ella was walking more normally, and obviously feeling much better.

Emotional Wounds

Ella’s physical improvement was fast; her wounds were nearly completely healed within a few days. It will take much longer, however, for the emotional scars to heal. She is now afraid to go into the backyard. Worse, she is showing signs of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including hypervigilance (constantly on the alert) and hyperreactivity (overreaction to movement and sounds coming from the direction of the backyard).

On Tuesday night, three days after the attack, Ella also began showing signs of anxiety disorder, including panting, pacing, trembling, trying to hide, and being unable to relax. This started in the evening while we were in my bedroom, which looks out into the backyard through a sliding glass door. I closed the blinds so that she wouldn’t be able to see out, but her behavior did not change. I took her for a short walk (about half a mile) in the hopes that the exercise and getting away from the house would calm her down. She was fine on the walk, but her anxious behavior resumed as soon as we returned home.

There’s a difference between anxiety and fear. Fear is related to something concrete. It is logical and it can be addressed with behavior modification, such as desensitization and counter-conditioning. It may take some time, but fear will diminish if properly handled.

Anxiety is different. It is a diffuse emotion, not specific to anything in particular, but more an all-over feeling of anxiousness, as though something terrible may happen at any moment. It’s heartbreaking to watch a dog who is truly anxious, as nothing you do helps. I know; my last dog, Piglet, developed generalized anxiety disorder, which destroyed her quality of life in her later years. I was able to keep her anxiety under control with the use of a lot of medication, but she was never again the confident dog she was before she developed the disorder.

Piglet’s anxiety started with a noise phobia that kept escalating, but I didn’t take it seriously enough until it was too late. I tried medication (buspirone) at one point, but when it didn’t seem to help, I quickly gave up. I later learned that my vet had not prescribed a high enough dose, which is a common problem.

On Wednesday morning, I called my vet. I wanted to start Ella right away on a long-acting drug, which can take several weeks to become fully effective, as well as getting a quick-acting drug to use on an as-needed basis. The vet prescribed fluoxetine (Prozac), a long-acting anti-depressant that also helps with anxiety; and clonidine, a short-acting drug that can be used when quick relief is needed.

Nicholas Dodman, BVMS, DACVB, Program Director of the Animal Behavior Department of Clinical Sciences at Tufts University’s’ Cummings School of Veterinary Medicine, is one of this country’s leading veterinary behaviorists. I learned at a seminar of his that Dr. Dodman prefers using clonidine over alprazolam (Xanax) for immediate anxiety relief, as clonidine doesn’t carry the risk of paradoxical reaction that alprazolam does. If the medications prescribed by my vet don’t work well, I will contact Tuft’s PETFAX Behavior Consultation service for further advice.

I started Ella on both medications right away. Together they had a minor sedating effect – she walked rather than trotted – but otherwise, she acted like herself, with no further signs of anxiety. I continue to give fluoxetine daily, which is not causing any sedation, and will keep her on that drug until she returns to normal and is no longer afraid to go into the backyard or reactive to sights and sounds coming from the yard in the evening and at night. I will use the clonidine only as needed while waiting for the fluoxetine to take full effect, or if something happens to increase her anxiety.

Overreacting?

Some of you may be rolling your eyes at this point, thinking you would never be so quick to drug your dog. I know, because I used to be one of those people. If I could do one thing over, I wish I could go back in time and start Piglet on medication before it was too late, before she developed the generalized anxiety disorder from which she never recovered. I will never make that mistake again.

When in doubt, particularly when anxiety is getting worse rather than better, I encourage everyone to use anti-anxiety medications sooner rather than later. Worst case, your dog doesn’t really need them and you’ll be able to wean her off quickly, but in some cases, it may change or even save your dog’s life. These medications are not dangerous and they don’t make your dog act “drugged.” They simply help dogs to overcome irrational anxiety, which they may not be able to do on their own.

Medications are not meant to replace behavior modification. Studies have shown that anxiety issues improve more quickly when anti-anxiety drugs are combined with behavior modification than when either method is used alone.

I have already begun working with Ella using treats and playing games to get her more comfortable near the backyard, and even occasionally going into the yard during the day, usually from a different direction (through the garage or gate rather than through the door where she was attacked). Ella and I recently began a Nose Work class, so I have her hunting for treats near the sliding glass door inside the house. (See “Sniff This – You’ll Feel Better,” WDJ April 2013, for more information on nose work.)

I debated skipping class on Monday, two days after the attack, but since she was moving well by then, I decided to take her, and it was the best decision I could have made. While a bit hesitant at first, she quickly got into the game and I saw her relax and start to show some of her personality again for the first time since the attack.

Since evening is when the raccoons are most likely to be out, and when she is more fearful, we do our behavior modification work during the day. I allow her to choose what she’s willing to do, giving her praise, encouragement, and food rewards for willingness to venture near and into “the scary place,” but never forcing her or even trying to coax her beyond her comfort level. This will be a long process that will take patience, but trying to rush things is only likely to make it worse, so we’ll take our time.

I was in touch with WDJ editor Nancy Kerns in the days after the raccoon attack, during which time, coincidentally, she was discussing an article with trainer and writer Nicole Wilde, the author of Help for your Fearful Dog: A Step-by-Step Guide to Helping Your Dog Conquer His Fears (Phantom Publishing, 2006). Nancy happened to mention what I was going through to Nicole, who very kindly responded with some advice for me.

Wilde suggested, “If there’s a dog your dog loves to play with, inviting that dog over to play in the yard could help more than anything.” She also recommended gradually feeding Ella closer to the backyard, petting Ella (or doing whatever Ella likes best) outside the door leading to the backyard, and playing games or feeding treats just outside the backyard (on the outside of the gate, not inside the house) and then gradually going in that way rather than going out through the house.

Wilde also suggested giving Ella alpha-casozepine, a component of milk that binds to the same receptors in the brain as valium and other diazapenes. Alpha-casozepine is marketed as De-Stress from Biotics Research in Canada and Zylkéne in the UK. Alpha-casozepine is also called Lactium, which can be found in a variety of supplements.

Ridding the Raccoon

Here’s another thing I didn’t anticipate: Having to keep dealing with the raccoon. It has returned each night since the attack. I called my local Animal Control Monday morning, and they suggested I contact my county’s Vector Control office, which I did. An agent came out Tuesday, along with my local animal control officer, to assess the situation.

The two men told me that the culprit was probably a female raccoon with babies in a den under my deck. They were unwilling to try to trap her, though. If she proved to be a nursing mother, they would either have to let her go (transforming her into a trap-smart raccoon who would never be caught again), or kill her (causing the babies to die a lingering death and then decompose under my deck). As much as I wanted the raccoon gone, these were not good options.

They suggested instead that I try to drive the raccoon away by playing loud music (they said big band music is best!) from 8 in the morning to 6 at night, so that she’d be unable to sleep and would move the babies somewhere else.

The agents also found what they called a “latrine” – a big pile of scat – on the side of my house. At their suggestion, I cleaned up all the scat, then poured both bleach and Pinesol over the entire area, in hopes this would smell bad to the raccoon. I also sprinkled cayenne pepper around the area, hoping that a snoutful of pepper would make the area even less enticing to a raccoon.

The county agent told me that if these steps did not work, he would come back and pour male raccoon urine around the opening under my deck, to further incentivize the female to move her young. Once I am certain there are no raccoons under there, I will hire a professional company with experience dealing with raccoons to seal off the opening so that no other animal can move in.

I asked the agents if they had any suggestions for fighting off a raccoon, should it happen again, but all they could tell me was to call 911, which of course would have taken too long. I’m sure it was dangerous for me to grab the raccoon, and I was incredibly lucky that things turned out as well as they did. I didn’t get injured at all, so there was no need for me to get post-exposure rabies shots.

In the meantime, I have installed brighter lighting outside, and carry a weapon of some kind with me each time I go outside with Ella. My favorite is a mop with a flat head that I feel I might be able to use to pin the raccoon down, if needed. I also ordered an airhorn – if it will scare off a bear, maybe it will work for a raccoon as well. The downside is that it would also frighten my dog.

Rabies

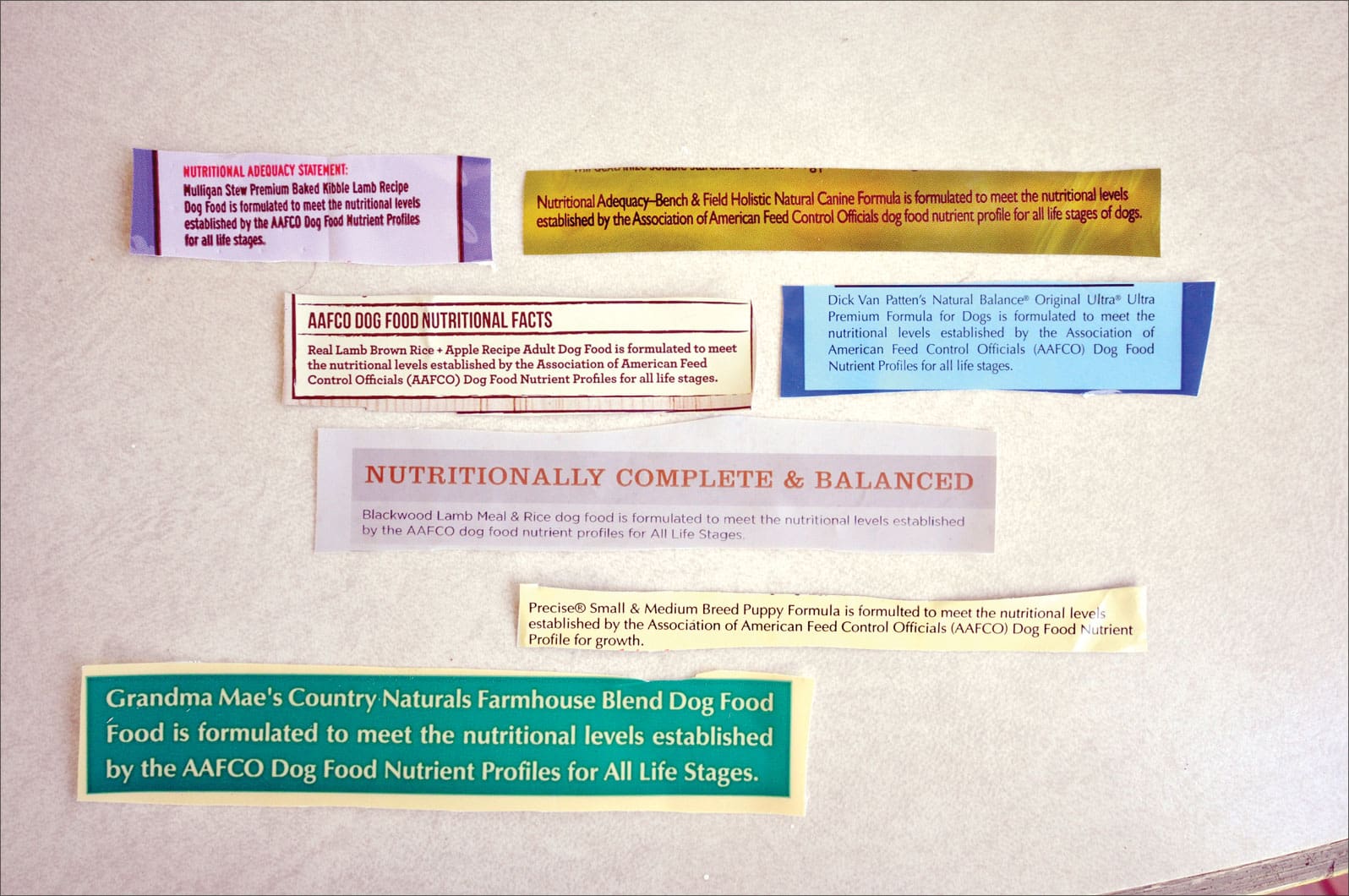

Ella was current on her rabies vaccination, thank goodness. Laws regarding possible rabies exposure vary from state to state, and local agencies are given a lot of leeway in enforcing these laws.

In California, where I live, if a dog is involved in an encounter with another animal whose rabies status is unknown, and that dog does not have a current rabies vaccination, the dog would either be euthanized (!) or would have to be quarantined on the owner’s property for six months. The vector control officer told me that California law requires dogs with current rabies vaccinations to be quarantined for 30 days. All dogs except those who have been vaccinated in the last 30 days are also given a rabies booster within 48 hours of a bite from an animal infected with rabies or whose status is unknown.

A friend (also in California) contacted her county animal control director, to find out whether this varies county by county, and was told that a 30-day quarantine was the minimum requirement, and they would increase that to six months if the attack was severe. Their argument was that no vaccine is 100 percent reliable, although the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) conducted a nationwide study of rabies among dogs and cats in 1988 and found “no documented vaccine failures occurred among dogs or cats that had received two vaccinations.”

I’ve heard of dogs being confiscated by local authorities after a run-in with a wild animal who were euthanized immediately due to a slightly overdue rabies booster. I’ve also heard from people who were told that their dogs would have to be quarantined in an animal control facility, at great cost to the owner (and great stress to the dog), rather than on the owner’s property, as the law generally permits. Be very careful about allowing anyone to take your dog; if possible, stay with your dog at all times while contacting a lawyer or someone else who can help if the authorities insist on taking your dog into custody.

While raccoons are the most frequently reported rabies carriers in the U.S., and the primary vector for the disease on the east coast, raccoons on the west coast almost never carry rabies. In California, bats are the most common source of rabies, with a handful coming from skunks and the occasional fox.

Progress

As of this writing (Saturday, one week after the attack), Ella is doing well, but I still see the raccoon nightly. She is no longer using the “latrine” since I cleaned it up, but I continue to check it daily. I just started playing the radio under my deck today, so I’m hoping that maybe she’ll move out in the next couple of days. If she is still around after I am certain there are no babies, I will have her trapped and killed; in California, it’s illegal to relocate raccoons, as they will most likely either become someone else’s problem (and now impossible to trap), or will starve in a new environment. I would strongly prefer to “live and let live,” but not at the risk of my dog’s life.

Mary Straus is the owner of DogAware.com. She and her Norwich Terrier, Ella, live in the San Francisco Bay Area.