You’re frustrated with your dog. Maybe even a little frightened of him. Since puppyhood he’s been a happy and loving companion, star of his puppy training class, soaking up new experiences without turning a hair. You were even thinking of making him a therapy dog. But in recent weeks he has started offering new behaviors that have you puzzled and alarmed. When you try to take him for a walk on leash, he grabs the leash and shakes it, or – worse – grabs at your clothing. At home, he will occasionally launch at you with no warning, biting your pant legs or shirtsleeves. It’s getting worse – becoming more frequent, and he’s biting harder. He’s turning into a shark, and you have the puncture marks dotting your arms to prove it.

This alarming behavior can start early, even with puppies as young as six to eight weeks (See “How an Intense Behavior Modification Program Saved One Puppy’s Life,” WDJ April 2012), and even more commonly appears in adolescence – perhaps an interesting canine parallel to human teenagers running amok. It often erupts when there’s been a period of prolonged inactivity, such as inclement weather preventing outdoor exercise, or an owner working unusually long hours. There may be a number of additional influences on this sharky, biting behavior:

– Early experience in the litter. Singleton pups (those who have no littermates) seem particularly prone to hard mouthing, as do pups taken away from their litters too early (prior to the age of eight weeks). Since they have no siblings to let them know they are biting too hard, they may fail to learn good bite inhibition. (See “Teaching Bite Inhibition,” June 2010.)

– Inappropriate play with people. I counsel my clients to avoid roughhousing with their dogs in a way that encourages the dog to make mouth contact with human clothing or skin. Although not always, it is often male humans who take pleasure in games of growly rough-and-tumble. I do my best to direct those activities to appropriate games of tug, where the human can play rough and the dog learns to keep his mouth on appropriate play objects. (See “Tug O’ War,” September 2008.)

– Inadequate physical exercise. There’s nothing like excess energy to prompt a young dog to use his mouth in play. I have fostered several puppies and young dogs who hadn’t passed their shelter’s assessments due to excessive mouthing, and in every case, ample exercise was instrumental in modifying their behavior.

– Inadequate mental stimulation. Add “boredom” to excess energy and you have a surefire recipe for disaster. This is the dog who is seriously looking for something to do with all his excess energy, and discovers that he can engage you in his games by using his teeth. Not a good solution!

The good news is that canine sharks are not a lost cause. There are remedies at hand, and most are quite simple to implement if you are willing to invest a little time and effort.

Life in the Litter

If you plan to adopt a pup from a shelter or rescue, you may (or may not) have the privilege of seeing the litter interacting together. If so, at least you know there’s a litter, so the singleton pup concern is not an issue. If you are purchasing from a breeder, be sure to ask how many pups were in the litter and how long they stayed together. Might as well sidestep a problem if you can!

If you get to watch littermates playing together, watch how it works. Usually, if one pup bites another too hard, that pup yelps or snarls and moves away for a moment. The pup who bit will normally readjust his play, re-engage his sibling, and play will continue. A pup who continues to bedevil his littermates and continues to bite hard even when they let him know they don’t like it is likely a shark in the making. Pick a different pup, or be prepared to deal with the behavior.

The best behavioral solution for a singleton pup is for the breeder, shelter, or rescue group to find two or three “spare” pups from another litter and import them with careful introductions to mom, so the pup has brothers and sisters. This is preferable to removing the singleton and placing it in a different litter, since mom will likely grieve the loss of her baby. The exception would be if she isn’t adapting well to motherhood and is not taking good care of the pup, or has some medical issue that prevents her from mothering.

If you somehow acquired a pup prior to the age of eight weeks, ask your dog friends and animal care professionals (vet, groomer, trainer) if they know of any litters of a similar age that your pup could spend time with (daily!).

Tug O’ War

I already mentioned the wisdom of playing a hearty game of tug-o-war rather than physical contact sports. Some old-fashioned trainers still warn against tug with gloom-and-doom predictions about dogs who are allowed to show their “dominance” and resulting “aggression” in the game. I had a client just the other day whose prior trainer said exactly that. He and his dog were as happy as a kid at Legoland when I gave them permission to play tug. The rules are short and simple:

Dog is not allowed to rudely grab tug toy from your hand; have him wait politely for permission (the cue) to grab. I use “Tug” as my cue. If my dog grabs for the toy before I give the cue, I give a cheerful “Oops!” and whisk the toy behind my back.

Make sure the dog will “trade” (give you the toy in exchange for something else) – either on cue, or for a treat.

Take several “trade” breaks from tugging during the game, in order to solidify polite good manners.

Canine teeth touching human skin or clothing is cause for a cheerful “Oops, time-out!” This uses gentle “negative punishment” (wherein the dog’s behavior makes a good thing go away) to teach your dog that the funs stops if his teeth touch human skin, and gives your dog a brief arousal break – time to calm down before play starts again.

Give That Dog Exercise

The last thing you may want to do when you come home exhausted from a day of work is exercise the dog. Your dog, however, has been lying around the house all day just waiting for you to come home to play with him, and you – or someone in your family, or a dog walker – has to oblige. That was the contract when you got him, remember? His excitement over your return and in anticipation of his walk put him at a keen edge of arousal, and tug-the-leash is a natural game choice for him. But you mustn’t allow yourself to get drawn into a game that usually ends with your dog overstimulated and you upset (or frightened or hurt)!

It behooves you to get rid of some of your dog’s energy before you take that on-leash walk. Of course he has to relieve himself after being indoors for hours. If you have a backyard, allow him to relieve himself there, and then play with him there before you try to take him for a walk. Play hard. Throw his ball. Throw a stick. Have him go over jumps as part of his fetch game. If he’s so aroused already that he’s grabbing at you while you play, put yourself inside an exercise pen you leave set up outdoors for that purpose (or behind your closed porch gate) and throw toys or play with a flirt pole from inside the pen until he’s tired.

Alternatively, if your dog’s not the fetch-’til-you-drop kind, go out in the yard and scatter small but tasty treats all over. He will exercise himself as he criss-crosses the yard in search of treasure, working his nose. (Nose exercise is surprisingly tiring for a dog.)

If you don’t have a yard, you probably have to take your dog out on a leash at first to let him eliminate using one of the management solutions described below. When he’s empty, bring him back indoors and play physical inside games such as tug, chasing toys or treats down the hall, until you’ve taken the edge off. Then put the leash back on and go for that walk! (Note: If you just rush him back inside when he’s empty and don’t play, or don’t go for the after-walk, your dog may learn to “hold it” as long as possible to enjoy the outing.)

Brain Exercises for Dogs

Mental exercise can be every bit as tiring as physical exercise. (I remember in the early 1990s coming home from work exhausted after trying all day to figure out how these new-fangled “desktop computer” things were supposed to work.) On those days when you can’t play in the yard with your dog (or if you don’t have a yard to play in), take advantage of the multitudes of interactive toys now on the market. Or make your own: treats in a muffin tin with tennis balls covering the holes can work nicely to occupy your dog and exercise his brain. In addition, sign the two of you up for a force-free basic good manners class. If you’ve already done basic, go for the more advanced classes. Brain candy. Once you have taken the edge off with physical or mental exercise, give your dog 10 to 15 minutes to calm down, and then put his leash on for that neighborhood walk. If he’s new to the leash-tug game, that may be all you need to do. If it’s a well-established behavior, however, you may need some additional management measures in order to help extinguish the game.

Manage Your Dog’s Behavior

Management is always an important piece of a successful behavior-change program. The more often your dog gets to practice (and be reinforced for) his inappropriate/unwanted behaviors, the harder it is to make them go away. Here are some ideas to get you by until your shark has turned into a pussycat.

– Choke Chain. Yep, you read that right. I love to watch the shock and dismay on the faces of my academy students when I tell them that this is the one time I will actually still use a choke chain. Then I pull out a double-ended snap or a carabiner, and snap one end of the chain to the dog’s collar ring, and the other to the leash. Voila! You now have 12 to 24 inches of metal chain between your dog’s collar and your leash. When he goes to bite the nice soft leash for a fun game of tug he bites on metal instead. Most dogs don’t like that – so they quickly learn that tug isn’t any fun anymore and stop trying to bite the leash.

– PVC Pipe. Slip a 5-foot piece of narrow-gauge, lightweight PVC pipe over your 6-foot leash. Again, your dog’s teeth have nothing soft to bite on, and they will slide right off the pipe. Additionally, although it is somewhat awkward, you can use the stiff pipe-leash to hold him away from you if he is trying to grab you or your clothing.

– Two Leashes. Snap two leashes on your dog’s collar. When he goes to grab one, drop it and hold onto the other. If he goes for that one, grab the first one again and drop the second. The fun of tug is the resistance you apply on the other end (because you can’t just drop the leash and let him run off). If there’s no resistance, there’s no fun (no reinforcement) and the game goes away.

– Tether. This one isn’t for all dogs, but works for some. Put a carabiner on the handle end of your (heavy duty) leash. When your dog starts grabbing at you, tether him to the nearest safe and solid object and walk a few steps out of reach. (Don’t use this one for dogs who will bite right through their leash, or who panic if you leave them.) Make sure you do not tether him where he can run into traffic or assault pedestrians. Return to him when he is calm. If he amps up on your return, step away again. Repeat as needed.

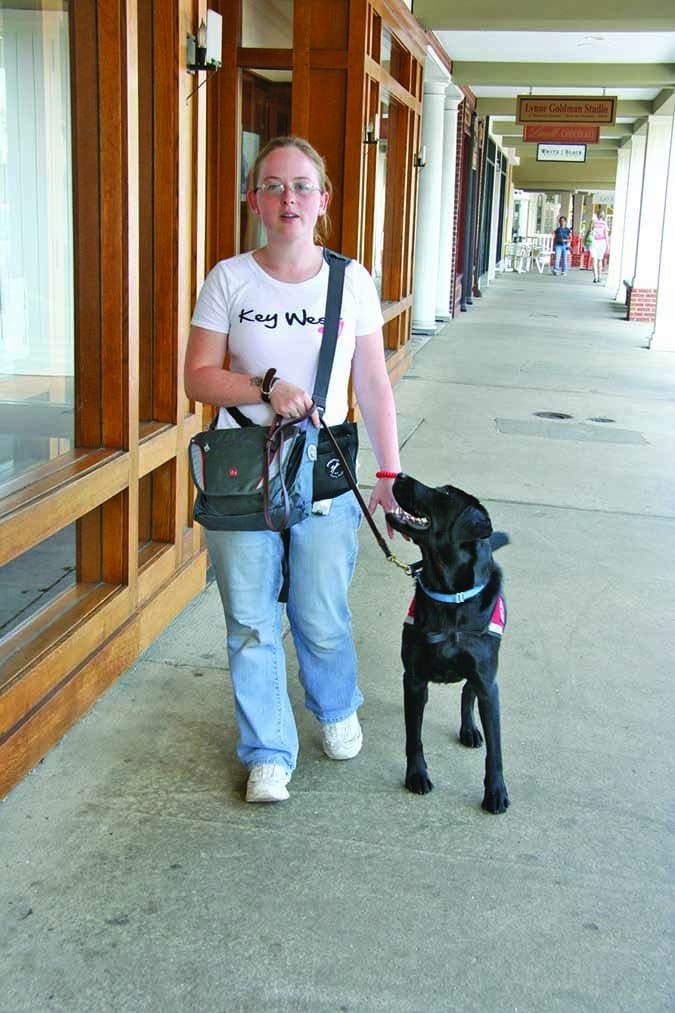

– Head Halter. These are not my favorite piece of training equipment (most dogs find them aversive), but this is one of the few times when the head halter may still have a place in positive reinforcement training, because it does give you control over the dog’s head in a way that a front-clip control harness does not. With a head halter, you can actually use the leash to prevent your dog from grabbing you with his jaws by putting pressure on the outside of the halter, away from you. If you are going to use one, however, you must take the time to convince your dog that a head halter is wonderful before you actually start using it. (See “Teach Your Dog to Love a Head Halter,” next page.)

– Baby Gates. While much of this unwanted behavior tends to happen out of doors, especially when on a leash, some dogs expand their aroused biting to indoor interactions as well. Pressure-mounted baby gates (so you don’t have to put holes in your door frames) are a quick and simple way to put a barrier between you and your shark when teeth are flashing. You can even exercise your dog indoors using gates, similar to the method described above with the exercise pens. Just stand on the opposite side of the gate from your dog and toss your heart out.

– Redirection. You often have some warning before the biting behavior occurs. You see the gleam in your dog’s eye, or he does a couple of puppy rushes around the dining-room table. Perhaps it always happens in a particular room, or at a certain time of day. Be prepared! Have a plastic container of treats on an out-of-reach shelf in every room, and when you sense a shark attack coming on, arm yourself and start tossing to divert his attention, redirect his teeth and give him some exercise, all at the same time. Remove yourself to the other side of a baby gate, if necessary.

– Muzzle. If your dog still manages to grab onto you despite all your efforts, you may want to consider conditioning him to a basket muzzle when he is with you. (This sort of muzzle is not the same as the kind often used for restraint in vet offices; basket muzzles allow a dog to breath, drink, and even eat, but prevent him from biting. Do not leave one on him unattended, however.)

This requires the same conditioning process as the head halter, so it isn’t a quick fix – and there is some social stigma attached to your dog wearing a muzzle. You might elect to use it when there are particularly vulnerable humans present (small children and seniors). If you choose to use one, follow the same steps outlined below, to convince your dog that his muzzle is wonderful.

It would also be a good idea to explore other energy-sapping activity options for your dog. Investigate doggie daycare, if there is a decent one in your community and your dog is daycare-appropriate. (See “Doggie Daycare Can Be a Wonderful Experience” November 2010.) A well-run dog daycare will give him great opportunities for exercise and social interaction.

A professional pet walker is another option, assuming you can find one skilled enough to handle your dog’s mouthiness and willing to follow your explicit instructions about how to work with the behavior. If there’s no good daycare in your area, find some appropriate canine pals for your dog and arrange playdates. If you can find another dog who has a similar style of playing, they can gnaw on each other to their hearts’ content and come home tired, so your dog can behave more appropriately with you.

Of course, if after all that you think there is an element of real aggression in your dog’s biting, or if the behavior is too overwhelming, by all means seek out the services of a competent, force-free behavior professional to help you through the shark-infested waters. Properly handled, your dog can outgrow this phase, and the two of you will be on to smooth sailing.

Why You Never Hurt or Scare a Dog

It should go without saying that we would never advocate verbally or physically punishing your dog, but just in case, here are five reasons why physically hurting or scaring your dog is a bad idea:

1. You can cause physical harm to your dog.

2. You aren’t teaching your dog what to do instead of biting. You leave a “behavior vacuum,” which he is likely to fill with the behavior he knows – being sharky.

3. You can inhibit your dog’s willingness to offer desirable behaviors due to his fear/anticipation of being punished.

4. You can damage your relationship with your dog, cause him to fear you, and teach him to run away from you.

5. You can turn your dog’s easily managed and modified aroused/excitement biting into serious defensive aggression.

Introducing a Head Halter

Your best chance for convincing your dog his head halter is a wonderful thing is to pair it with high-value treats from the very beginning (this is classical conditioning). At first, and between steps, put the head halter behind your back. This process should take at least several sessions. If your dog is happily going along with the program, it’s fine to continue – but try to always stop before he becomes unhappy with the process. If your dog becomes anxious at any point, or resists the process, back up to an easier level and then figure out how to add more steps in between. If your dog starts fussing, distract him to stop the fussing, and then take the halter off after a bit and slow your training program. Here are the steps (repeat each step many times):

1. Show the dog the head halter and feed him a tasty treat. Repeat until his eyes light up when you bring out the halter.

2. Let him sniff/touch the halter with his nose and feed him a tasty treat. Repeat until he is deliberately and solidly bumping his nose into the halter.

3. Let him sniff through the nose loop of the head halter. Feed him the treat through the nose loop. Repeat until he eagerly pushes his nose into the loop.

4. Attach the collar around your dog’s neck (without the nose loop) and feed him a treat. Remove after one second. Repeat many times.

5. Attach the collar band around your dog’s neck (without putting the nose loop on) and feed him a treat. Gradually increase the length of time that the collar is on your dog.

6. Let your dog push his nose into the nose loop. Keep the loop on his nose for one second. Feed him a treat. From now on, feed all treats through the nose loop.

7. Let your dog push his nose into the loop, gradually keeping it there longer and longer, until he is holding his nose in the loop for 10 seconds. Treat several treats. This should take many repetitions.

8. Let your dog push his nose into the nose loop, and then bring the collar straps behind the head for a second or two. Do not fasten them. Feed him a treat and remove the nose loop.

9. Repeat the previous step, gradually keeping the head halter on longer and longer, until you can hold it there for five seconds. Treat several times.

10. Put the head halter on and clip the collar behind his head (without a leash attached to it). Treat and remove the collar. Repeat many times, gradually leaving it on longer and longer. Treat generously.

11. Put the halter on (without a leash attached to it) and invite your dog to walk around the room. Feed treats.

12. Attach the leash and take your dog for a short walk – in the room at first, then gradually longer, and outside. Be generous with treats. Now you can use the leash and head halter to gently move his head away from you if he starts to get grabby.

Here is an excellent YouTube video of the wonderful force-free trainer, Jean Donaldson, conditioning her Chow, Buffy, to love a head halter.

Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, is WDJ’s Training Editor. She lives in Fairplay, Maryland, site of her Peaceable Paws training center.