I prowled the aisles for over an hour, shaking my head in wonder and appreciation for the amenities in the store, and the sheer volume of quality products therein. It felt heavenly to a dog-food and dog-equipment geek like me. But at one point, as I was examining all the brands and varieties of dog food in the dry food aisles, I found myself crossing paths several times with another shopper. After the third time that I sidestepped out of her way saying, “Sorry, excuse me” without taking my eyes off the shelves, I finally made eye contact with her. I smiled and said, “I don’t work here, but can I help you find something?” She laughingly replied, “If I knew what I was looking for, I’d tell you. There are too many foods here! I can’t tell them apart and I don’t know what to get!”

I agreed with her that the selection was overwhelming – but in my view, it was overwhelming in a good way. I love having a lot of products to choose from! But then again, I know what I’m looking for and feel confident when reading labels. When it’s time to buy food for my dogs, I find it interesting and even enjoyable to move down the aisles checking ingredients lists and “best by” dates as I go: “No. No. Nope. Wow, no way. Hmm, maybe. Maybe. Yes! Here we go! Yes! Whoops! No again!”

The encounter was a good reminder that I may be in the minority in this; some dog owners feel oppressed (rather than excited) by the sheer number of choices at their local pet supply stores. “Read the label,” we always advise in WDJ, but where should they start? What information is trustworthy and important on the label, and what text is hyperbolic marketing gobbledygook? How can a dog owner choose?

Hey, take a breath! Relax! Allow me to explain the top five things to look for on a dog food label.

1. Start with the ingredients panel, Looking for real food ingredients.

That might sound silly, but only if you’ve not yet taken the opportunity to read the ingredients on at least one variety of each company’s dog foods in your local pet supply store. If you’ve never done this, do it as soon as you can; you may end up slightly horrified, because the vast majority of dog foods on the market are comprised of ingredients that bear only a passing resemblance to food.

Look for products with ingredients that you can readily identify as actual food ingredients. If you couldn’t explain to someone what a given ingredient is, it probably isn’t a good thing. If you don’t know what may or may not be legal to include in something like “meat and bone meal” or “chicken by-product meal,” perhaps you shouldn’t feed it to your dog. If you can’t immediately visualize what is meant by “corn gluten meal” or even “brewer’s rice,” you can bet that it’s a waste product from some human food manufacturing process – meaning it’s been processed in one place and then shipped to another, losing freshness and vulnerable to adulteration along the way.

In contrast, things that sound like whole, real food ingredients are desirable – things like chicken, duck fat, rice, oats, apples, or carrots.

As you are looking for real food ingredients, focus on nouns and ignore the adjectives. It can be difficult to disregard the influence of descriptive words, but at least try to be aware that they are present specifically in order to manipulate you. Apples are great; they don’t have to be “fresh, whole, Red Delicious” apples in order to provide beneficial flavonoids and soluble fiber. “Sun-cured” alfalfa is alfalfa; “whole ground brown rice” is brown rice.

Don’t concern yourself too much about the ingredients that sound like chemicals that appear low on the ingredients list. Virtually all dog foods contain vitamin and mineral supplements; if you look them up, you’ll find that most of those chemicals are some vitamin or mineral source.

Owners who get really into food will be picky about these, too – looking for only chelated minerals and food-sourced vitamins, and eschewing anything synthetic. If you are a label-reading novice, don’t worry about any of this for now. There are bigger, far more important details to worry about – things that can have a much greater impact on your dog’s well-being.

2. Look for meat.

That is, named meats such as chicken, turkey, duck, lamb, beef, pork, or rabbit. I know it’s confusing, but you don’t actually want to see the word “meat.” “Chicken” can contain only chicken, but “meat” could be just about anything.

The more named meat there is in dog food, the better, so you want to see these named meat sources as high on the ingredients list as possible – ideally, in the first couple of positions on the ingredients list. Remember, on all food labels, for humans and dogs, the ingredients are listed according to how much weight they have contributed to the food. There is more of whatever is listed first on the ingredients list than anything else on the label, so the first thing on a dog food ingredients list ought to be a (named) meat.

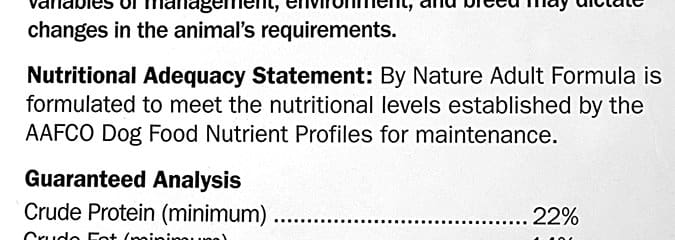

3. Now look for the “guaranteed analysis” box and check the protein and fat levels.

Do you know how much protein and fat is present in the food you currently feed your dog? You don’t?! Well, you should – because otherwise, how else would you know whether the new food you are thinking about buying contains twice as much protein and three times as much fat as the one you have been giving him? Go now and look at the label of the food you already have, and note those numbers somewhere.

The range of protein and fat levels in the variety of dog foods present in any given pet supply store will astound you in their breadth. If you’ve always been under the impression that “dog food is dog food,” you will be stunned to learn that one food may have three or more times as much protein and fat than the food sitting next to it on the shelf. There really isn’t a single “ideal” number for all dogs; you have to take your own dog’s age, breed, size, weight, activity level, and health into account when choosing a food that has the “right” amount of protein and fat. And you have to know where your dog is now – how much protein and fat he is already being fed – to know what effect a new food with different amounts of protein and fat will likely have on him.

Pay no attention whatsoever to phrases including Light, Lite, Healthy Weight, Reduced Calorie, and so on. Look at the protein and fat numbers on the Guaranteed Analysis – that’s all, because one company’s “Reduced Calorie” food may contain twice as much fat as another company’s regular Adult food. It’s just another place where you have to dismiss the adjectives and look at the bottom line.

Speaking of calories, you can look for a number, but you may not find it (the calorie content of foods is not yet required on dog food labels in every state) – and you may not be able to easily compare one food’s calorie content to another product’s. One might list kilocalories per cup of food, and another might list kilocalories per kilogram of food. The protein and (especially) the amount of fat listed on the Guaranteed Analysis will be a more useful guide.

4. Look for the product’s “AAFCO” statement.

You will find the words “complete and balanced” on almost every dog food label – sometimes, in many places on the label. But this phrase, which means that the product contains all the nutrients your dog needs, only really counts in one spot: where it references the Association of American Feed Control Officials (AAFCO). No, that’s not a branch of the government you’ve never heard of; it’s an advisory group that establishes standards that are adopted by (and regulated by) feed control officials in each state. Pet food may not be labeled as “complete and balanced” in any state unless it has one of two possible statements on it: one referencing AAFCO “animal feeding trials” that have confirmed the nutritional adequacy of the food; or the other, indicating that the food has been formulated to meet the AAFCO nutrient guidelines (or “nutritional levels established by the AAFCO Dog Food Nutrient Profiles”).

We’ve explained the differences between and compared the relative merits of these two statements in several past articles in WDJ, and discuss them briefly in all of our annual dry and wet food reviews. For now, though, as long as the product has one statement or the other, let’s not worry about that. To make sure you are buying an appropriate food for your dog, the words you really need to notice in this statement have to do with the dogs mentioned within the statement. Does the statement say the food is complete and balanced for “all dogs,” “puppies,” or for “maintenance” (sometimes specified as “adult maintenance”) only? If it says it’s for “all dogs” (or “all life stages”), the product meets all the standards. The nutrient requirements are the lowest for products labeled as for “maintenance only.”

Note that if a pet food label does not say it is “complete and balanced” anywhere, it should have a statement saying that it is for “intermittent or supplemental feeding” only. It should be obvious that a food labeled thusly should not be used as a dog’s sole diet.

By the way, you may have to look really hard for this statement. It might be just a line or two of really small type, located somewhere inconspicuous. But it has to be there by law; check it out.

5. Find and check the date code and/or “best by” date.

Every product label will have a code stamped on it somewhere, identifying where and when the product was made. These batch codes are used to identify the origin of the product in case of a recall or any problem with the food. However, thatinformation is coded; you won’t be able to find out exactly which manufacturing plant in which state made the food. If you have a problem with the food, and give the date code to the pet food company, they will know, and will use the information to look up batch records and perhaps test their own retained samples from the same batch.

While you are standing in the pet supply store, looking at labels, none of that information is important; I only mentioned all that because sometimes the batch code is incorporated into the date codes, and sometimes it’s stamped on the bag separately. When you are about to buy your dog’s food, the critical part of any coding you can find on the label has to do with the date of manufacture. You need to know how old that particular container of food is, because the older it is, the more likely it is to have lost nutritional value. This is less of an issue with canned foods, because they last far longer. But with dry dog foods, the age of the food has everything to do with its potential rancidity. For in-depth information about this, see “Fats’ Chance,” in WDJ’s December 2012 issue. Suffice to say here that rancid (oxidized) fats are really bad for dogs.

Again, though, just to make things a little more challenging than they really should be, this information will be hard to find and inconsistent from brand to brand and label to label. Some companies stamp their bags with a date of manufacture; this requires you to be knowledgeable about how long the food should be expected to last. Other companies use a “best by” or expiration date; that’s far more helpful, but understand that food that is close to these dates is actually months older than it ought to be; ideally, the product would be consumed by your dog within a couple of months of its manufacture. It’s best of all when the company stamps the product with both dates – the manufacturing date and the “best by” date, so you stand the best chance of identifying the freshest product possible.

Consumers who are armed with this information are

hard on store owners, because they rifle through the nice neat stacks of food and reject the sacks on the top of the piles, which the stock persons have placed there hoping to sell them first, before they expire.

A really good store manager will understand the importance of selling you the most wholesome product possible, however, and will want your dog to have the best possible digestive experience with the food, so you come back to her store and buy some more. What’s more, good managers manage their product orders carefully, so they aren’t stuck with literal tons of products that are close to their expiration dates. If a salesperson gives you a hard time about sorting through the stacks (looking for freshly made foods), or if there are no relatively freshly made foods available, look for another product to buy.

After 17 years of writing about dog food, I still learn new things about the industry and canine nutrition, but these five label-reading tips will do more to help you find an appropriate, healthy diet for your dog than everything else. So grab your reading glasses and start with the label of the food you currently feed! I promise you will learn something new and interesting.