Muzzles, and the dogs who wear them, often get a bad rap, as many people associate them with dogs who may display aggressive behavior. In reality, there are plenty of reasons why even the most mild-mannered, sociable dogs might need to be muzzled, along with numerous situations where using a muzzle is an act of responsible dog ownership.

Muzzles can be used to help keep people and other animals safe in a variety of circumstances:

✔ In an emergency. When a dog is in pain, fearful, and/or pushed past her limits, she may pose a bite risk, so the use of a muzzle keeps everyone safe.

✔ As “insurance” when working through a training plan. A muzzle can be a valuable tool to help ensure the safety of other people and animals when working on a behavior modification program. A muzzle should never replace training to address the root of the issue that leads to the potential bite risk, but it’s a great safety net in case things don’t go as planned during a training session.

✔ As a supervised management tool. In some cases, a muzzle can be safely used to prevent the ingestion of dangerous items, while allowing the dog to explore on a walk; to prevent the dog from harming wildlife; or even as added security in situations where you aren’t sure how the dog will react.

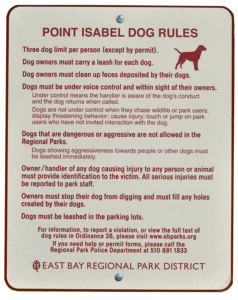

✔ When required by law. In some areas, dogs – or certain breeds of dogs – are required to wear a muzzle when in public.

TYPES OF MUZZLES

There are two basic types of muzzles:

* “Basket” muzzles encase the dog’s snout in a basket with straps fastened around the neck and head. They are typically made from plastic, rubber, or silicone. While a basket muzzle limits the degree to which a dog can open its mouth, a properly fitted basket muzzle allows the dog to relax its mouth enough to pant. The open weave of the basket makes it possible for the dog to eat and drink, making a good choice for muzzle-training programs.

* Then there are muzzles that encase the snout like an open-ended sheath and buckle around the neck. Sometimes called “soft muzzles,” “sleeve muzzles,” or “grooming muzzles,” they are usually made from nylon, mesh, or leather. They are more restrictive than basket muzzles, and prevent a dog from opening its mouth enough to pant, so they should be used only for a few minutes at a time, and not outdoors (where the risk of overheating is greater). These muzzles are often used in vet hospitals or by groomers for brief periods to protect handlers from a dog who is frightened or in pain.

SLOW IS FAST

Teaching your dog to be comfortable in a muzzle is important. We don’t want our dog to simply submit to the muzzle, letting us put it in place without an objection. We want our dog to feel really good about the muzzle.

It’s important to build a slow, thoughtful development of a positive association with the muzzle – as opposed to simple tolerance – because behavior degrades under stress. If under the best circumstances – relaxed at home, free from pain, away from potentially scary things – your dog only tolerates wearing a muzzle, the introduction of such stressors can lower the dog’s tolerance to “I hate everything that’s happening!”

In contrast, however, if you’ve taught your dog to feel really good about the muzzle, even if the behavior of wearing a muzzle degrades, it may only decrease from “I like my muzzle!” to “I can tolerate my muzzle.”

Muzzle training is not just about physical safety; it’s also an investment in your dog’s emotional health and well being.

A quality basket muzzle should be lightweight, adjustable, and have options for added security to prevent the dog from removing the muzzle. We like the Baskerville Ultra muzzle. It has an additional strap that connects the top of the muzzle to the neck strap, along with a loop to further secure the muzzle to the dog’s collar. It can also be heat-shaped with a hair dryer or hot water to create a customized fit.

When properly fit, there should be a small gap between the dog’s nose and the end of the muzzle, and the open-end of the basket should sit below the dog’s eyes. The diameter of the basket should allow the dog to partially open his mouth to pant. You should be able to fit one finger between the edge of the muzzle and the snout, as well as between the straps and the dog’s neck.

Brachycephalic breeds like Pugs, Bulldogs, and French Bulldogs can be more challenging to fit with a muzzle due to their short snouts. Many do better in a mask-style mesh muzzle (designed specifically for such breeds) that covers more of the dog’s face, but has eyeholes to keep from obstructing the dog’s vision.

MAKING MUZZLES MAGICAL

These three steps will help your dog develop positive feelings about seeing and wearing a muzzle. We recommend working with a basket muzzle, as it’s less restrictive and easier to use with treats.

1. Muzzle means delicious treats. Hold the muzzle in one hand and feed your dog tiny, delicious treats from the other hand. After a few treats, put the muzzle behind your back and stop feeding. Continue this process, moving the muzzle closer to your dog’s face, until you can present the muzzle right next to your dog’s face and he’s happy to eat offered treats.

Repeat this process three to five times per day for several days. Practice in different rooms. After a few days, your dog starts to think, “I’m not sure what this is, but when it comes out, I get treats. Cool!”

2. A basket of treats. After a few days of being fed by hand when the muzzle comes out, we’re ready for the dog to move toward the muzzle.

If you have already taught your dog a nose-target behavior (often called “touch”), ask for a touch as you present the muzzle. Reward your dog for targeting any part of the muzzle – but to encourage him to actively insert his snout into the muzzle, deliver the treats within the basket.

If your dog is leery of putting his snout into something restrictive, work on that ahead of time with an easier object, such as a food bowl or water bucket. If your dog shies away as you move to adjust his collar, work on this separately, to prepare your dog for having your hands over his head as you buckle the muzzle and adjust the straps.

The goal is to work this step until the dog is happily shoving his face into the muzzle basket for treats. You can test the strength of the behavior by slowly moving the muzzle away from your dog as he moves toward it, making him try harder to land his snout in the “sweet spot.” The dog should move toward the muzzle; don’t move the muzzle toward the dog.

3. Buckle up, buttercup! Once your dog is happily shoving his snout into the basket, it’s time to work on keeping the snout in the basket as you buckle and adjust the straps. A dollop of squeeze cheese (or peanut butter or something similar) applied to the inside of the basket frees up your hands to handle straps. Time your strap-handling so that you’re able to buckle or adjust – and then remove the muzzle – before your dog finishes licking the reward. We want the dog to think, “Hey! I wasn’t done yet. Put that back on!”

Work up to the point that your dog accepts the muzzle for longer periods of time and, eventually, in the absence of frequently flowing treats – especially if your dog will need to wear a muzzle while on walks or when with other dogs. If your training is primarily for emergencies, don’t forget to periodically revisit the “magic muzzle” training to remind your dog the muzzle is a good thing.