So much of what’s on dog food labels has to do with marketing, rather than nutrition. The phrase “limited ingredient” falls somewhere in between.

There is no agreed-upon definition for “limited-ingredient foods.” In some cases, pet food makers use the phrase to designate foods that contain only one animal protein source and one carbohydrate source; these products may contain very few ingredients overall… but this is not always the case. In some cases, using only a single animal protein source results in a food that contains less protein than the pet food maker wanted, so a plant protein source (or two, or more) are added.

By the way, no matter how “limited” the formula is, it may appear to contain dozens of ingredients. The pet food makers don’t really consider all the ingredients that go into their vitamin/mineral pre-mix when they call a food “limited ingredient,” even though they have to name each of the ingredients included in that pre-mix on the list of ingredients on the product label. Generally, when the phrase is used, it’s meant to mean all of the major ingredients, not the vitamins and mineral sources, and certainly nothing that’s named among or below those sources on the ingredients list. (Since the ingredients are listed by the weight of their inclusion in the mix, anything that’s included in the same amount or less as some individual vitamin or mineral is present in the food in a very small amount – not enough to worry about for any but the most allergic dog ever.)

What advantage is there to a limited ingredient diet? A small ingredient list isn’t a virtue in and of itself; it’s only particularly helpful to dogs who are allergic to or intolerant of several food ingredients.

A review: An allergy involves an exaggerated or pathological immunological reaction (often referred to as a hypersensitive immune response) to a benign substance. True allergies cause the immune system to produce antibodies called immunoglobulin E (IgE). In dogs, allergies usually cause extreme itchiness; digestive issues such as diarrhea and vomiting are not out of the question, but they are far more rare than itchy skin (including itchy paws and ears).

A food intolerance, in contrast, is something that causes an adverse reaction such as vomiting, diarrhea, and extreme gassiness.

SUBSCRIBERS ONLY: Whole Dog Journal’s 2022 Approved Dry Dog Foods

Dog food elimination diet trials

The best way to find out which food ingredients your dog is allergic to or intolerant of is to conduct a dog elimination diet trial. In this sort of trial, you feed your dog an extremely limited-ingredient diet – generally a home-prepared diet consisting of a single animal protein source and a single carbohydrate source. The protein and carb are selected for novelty – something the dog (one hopes) hasn’t ever eaten before. For example, you may try bison for protein and barley for carbohydrates. This diet (and nothing but this diet) is fed for a few weeks while the dog is watched carefully for reactions. If he remains symptom-free, then a single new ingredient is added to the diet – perhaps another protein source – and he’s again watched carefully to see if any symptoms arise.

If he responds at any time with symptoms, the ingredient that was added most recently is suspected of causing his allergy or intolerance and removed from the diet until he’s free of symptoms again. From then on, the owner tries to make sure the dog’s diet is free of that/those ingredients. (For more about food-allergic dogs and how to conduct a food elimination trial, see this article.)

If you don’t know what food ingredients your dog is allergic to or intolerant of, you might find a limited-ingredient diet that doesn’t contain the ingredients that are problematic for your dog by sheer dumb luck. That’s great if you never change his food again, and if the manufacturer doesn’t ever change the formula, and if your dog doesn’t develop an allergy of/intolerance to any more ingredients (it happens). But a food-elimination trial is really the way to go, so you know what you are avoiding.

Dogs who are allergic to or intolerant of several or lots of common food ingredients (or even more) are the most difficult to find commercial diets for. They are the ones that a truly limited-ingredient diet is helpful for – as long as the product doesn’t contain the specific ingredients the dog is allergic to or intolerant to.

Use our searchable database to find limited ingredient dog food!

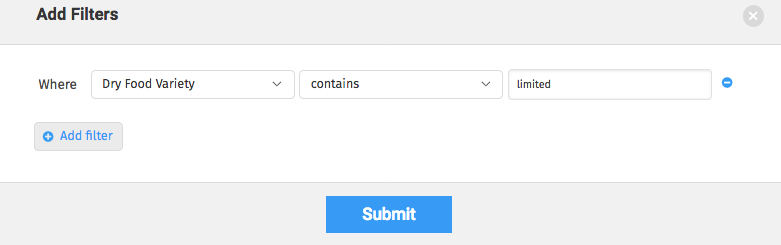

How can you find limited-ingredient foods? Well, it’s not the easiest task, mostly because (as I said earlier) there is no specific definition of the term. But some manufacturers who are taking this tack try to include “Limited Ingredient” in the product name – and these we can capture using the “approved food” searchable database on our site. I searched for the word “limited” in the “dry food variety” field and got 23 results. I expanded the ingredients list field on each food, to see exactly how “limited” they were.

The most limited-ingredient products (shortest ingredient list) on our list are Taste of the Wild products in their “Prey Limited Ingredient” line. The Beef variety contains just four major ingredients: beef, lentils, tomato pomace, and sunflower oil. The Turkey and the Trout varieties have the same formula, with just the different protein (turkey, lentils, tomato pomace, and sunflower oil in the Turkey variety and trout, lentils, tomato pomace, and sunflower oil in the Trout variety).

How do we define “major ingredients” in dog food? Essentially, we’re talking about the protein, carb, and fat sources high up on the label. As soon as you get into things like “natural flavor,” which comes next on the label, you are no longer in the land of “major” ingredients.

Personally, I’m not such a huge fan of products with a legume (or legumes) representing so much of the formula, but if your dog is intolerant of grains and legumes seem to suit your dog, fine!

Triumph Pet Food has a product called Limited Ingredient Lamb & Brown Rice in its Wild Spirit line with just six major ingredients: deboned lamb, lamb meal, brown rice, whole barley, peas, and chicken fat. I like the fact that the peas are lower down on the list of that product, but this is a personal preference.

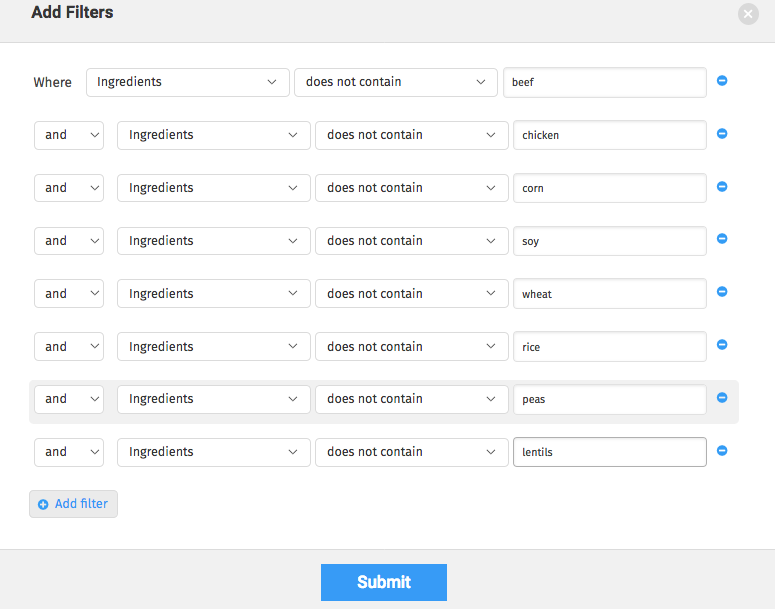

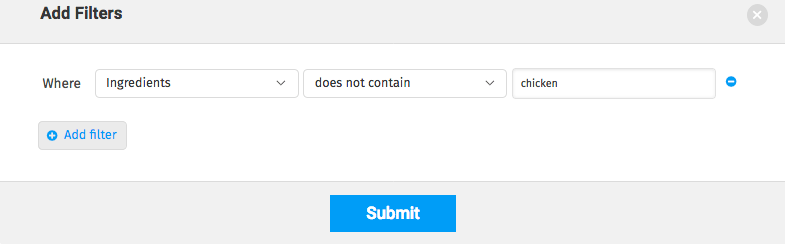

You might find other dry dog foods on our “approved foods” list that have short ingredient lists but without the word “limited” in the name. It would be best if you knew exactly which ingredients you were trying to avoid because then you could simply build a search that omitted all of those ingredients – like a soy-free, corn-free, wheat-free, rice-free, and chicken-free dog food. Something like this example:

That search resulted in 73 prospects to look over – pretty good for your dog food search when your dog suffers from several food allergies!

SUBSCRIBERS ONLY: Whole Dog Journal’s 2022 Approved Dry Dog Foods