CANINE IMMUNE SYSTEM SUPPORT OVERVIEW

– Support your dog’s immune system with fresh foods, ample (not necessarily strenuous) exercise, daylight, and loving, hands-on attention.

– Don’t overvaccinate! Use titer tests to determine whether your dog’s immune “memory” needs “boosting.”

– Take your dog’s chronic health problems as a sign that you need to take further steps to balance him immune system; the complementary therapies are excellent in this regard.

The immune system is a dog’s “great protector.” To be immune (from the Latin immunis, meaning free or exempt) is to be protected from infectious diseases by either specific or nonspecific mechanisms.

It is the great protector’s job to respond to infectious challenges and antigenic stimuli from the outside world and respond to them appropriately. An appropriate immune response will mount a defense against the body’s challengers without in turn destroying the host animal itself; this type of response presupposes that the immune system can recognize or differentiate its “self” from the invader, the “not self.”

Studies of the immune system include its basic structure and function along with all the biological, serological, physical, and chemical aspects of the immune phenomena. In addition, immune function is involved in immunization (vaccines), organ transplants, and blood transfusions.

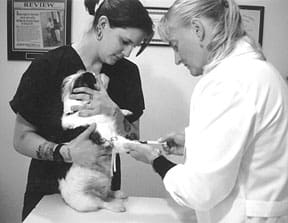

Functional testing of the immune system may include laboratory tests of the cellular and humoral (pertaining to the “humors” or fluids of the body, especially involving the blood) components of immunology, and the use of antigen-antibody reactions (serology and immunochemistry). Easy-to-perform clinical pathology tests (a CBC or needle biopsy, for example) might be used to indicate the current status of the animal’s immune system.

The physical part of the dog’s immune system extends from the subcellular level to the whole organism. Each and every cell and all organ systems have their own components of immunity, and in turn, each has some sort of independent, inner regulator. Recent evidence indicates that an animal’s emotions have a profound effect – sometimes positive, sometimes negative – on an animal’s immunity. And even environmental factors such as noises, odors, light patterns, and/or environmental pollutants can have an effect on the biochemistry and cellular components of the immune system.

The immune system has been extensively studied by the reductionist model of Western science. From the viewpoint of the holistic practitioner, however, the most important aspect of the system as a whole is that each individual component of immunity is intimately connected. Through these connections all the microscopic parts of the system are in constant and intimate communication with all other parts.

It is this inner communication that becomes important when taking a holistic approach to the dog’s wellness. While Western medicine typically concentrates on confronting one component of a disease, holistic medicine tries to incorporate all aspects of that great protective inner web and outer blanket that is the immune system, ultimately trying to bring them all back into balance. “Balance” is the operative word here – imbalance in either direction, either a hypoactive or hyperactive immune system, will ultimately lead to disease.

The Canine Immune System

The best-known components of the immune system are those found in the blood and lymph systems – the circulating immune system. Lymphocytes and immunoglob-ulins tend to be the media darlings of the immune system. Many practitioners give short shrift to other, equally important components, such as the skin and other body barriers, the mucosal linings of many body surfaces, the gastrointestinal tract, the lungs, hormonal input into the system, and the interconnecting immuno-communication system.

Traditionally, the circulating immune system is divided into two components: cellular (primarily lymphocytes) and humoral (complex proteins that are referred to as immunoglobulins or antibodies).

Cellular components of this circulating system include two types of lymphocytic cells: B-cells and T-cells. One purpose of the lymphocyte population is to recognize antigens. An antigen is any substance that is capable of inducing an immune response; bacteria, viruses, and parasites are antigens.

After recognizing a substance as “not self” and “not-good-for-the-self,” lymphocytes may enter directly into the process of destroying and removing the foreign intruder. Or, via the production of antibodies (immunoglobulins), they can activate other cells – including the white blood cells, neutrophils, eosinophils, and monocytes – that do the dirty work for them. Total white cell numbers and the ratio of the kinds of white cells seen in a sample (observed on a CBC, or complete blood count) may be helpful in determining the type of disease present (see “How to Utilize Your Dog’s Next Blood Test,” November 2003).

There are several classes of T-lymphocytes: helper cells, cytotoxic cells, and suppressor cells. Each class acts in its own way as a coordinator and/or stimulator of the immune system. In addition to their actions on the circulating white cells of the blood, T-cells also influence lymph nodes, the thymus, spleen, intestines, tonsils, the normal flora of “good guy” bugs that exist in various areas of the body, and the mucosal protective coating that lines many tissues.

B-lymphocytes are the memory cells of the immune system, and they are the cells primarily responsible for humoral immunity. B-cells produce proteins termed immunoglobulins that act as antibodies, and these antibodies interact with antigens that have been introduced to the body. This interaction typically forms a protein complex that can be removed from the body.

There are several classes of immunoglobulins: IgA, IgE, IgG, IgM, and IgD. The immunoglobulins are found in the gamma globulin portion of the blood serum. Each immunoglobulin class has a typical area of the body where it is most often found; each has specific antigens it interacts with, and each has its own way of producing a removable antigen/antibody complex.

For example, IgE activates immediate hypersensitive reactions, and IgA is generally involved with immune functions of the secretory organs. IgG is the only class transferred across the placenta, and it is responsible for the maternal antibodies that protect puppies for several weeks after birth.

There are specific tests used to determine the class and the relative amount of immunoglobulin present. While these tests are generally nonspecific, they may give some indication as to the type of ongoing disease process.

B-cells are long-lived, perhaps as long as the entire life-span of the animal. As they are exposed to antigens throughout their lifetime, B-cells store the memory of these antigenic exposures so that they can mount a response against them when exposed at a later date.

Vaccines rely on stimulating B-cells so they will be encoded with a memory of the specific antigen found in the vaccine. The idea of the vaccine antigens is to provide this memory of the antigen without causing disease (we hope!); this memory will then (again, we hope!) stimulate an appropriate response to an actual exposure to the antigen at a later date.

Depending on the health status of the individual, lymphocytes comprise some 20 to 40 percent or more of the cells in the blood, and they also have their own method for circulating throughout the body: the lymphatic system. Unlike blood, which is pumped throughout the body by the heart, the lymph system has no active pump and thus has to rely on muscular activity to move its lymphocyte-rich fluids from one area of the body to another.

Lymph nodes occur at various points along the body’s lymphatic circulation. They are accumulations of lymphocytes and other cells including macrophages (literally, big eaters), cells that kill, eat, process, and eliminate foreign substances.

In healthy animals the lymph moves as a seamless river, transporting immune information from one part of the body to another, bringing activated lymphocytes to areas where they are needed, and helping to remove accumulations of debris and toxins. Lymph will flow into an area of inflammation, and contribute to the swelling that occurs there. Fluid lymph can also accumulate and contribute to edema whenever an animal (or a normally moving part of the animal) is inactive for any length of time, and noticeable swelling may result.

Even in the healthy animal some lymph nodes are large enough to be located by palpation in certain areas (especially along the neck and hind legs), but they can also enlarge into very visible lumps when they are actively draining an infected area or when affected by tumors – lymphosarcoma, for example, or other tumors that have metastasized to the regional lymph nodes. Simple needle biopsies can be helpful in determining the cause of lymph node enlargement.

In addition to the moving (lymphatics) and stationary (lymph nodes) network of the lymph system, lymphocytes are a prominent part of other parts of the body. In fact, the largest accumulation of lymphoid tissue in the body is located in the gut (more about this below).

The new kids on the block of the immune system are the dendritic cells. Dendritic (branched like a tree) cells are difficult to isolate, so study of them is in its infancy, but they may prove to be one of the most important components of the immune system.

Dendritic cells are generally located where maximal microbial encounters occur – the skin, gut, and lung. They can be thought of as local surveillance cells, acting as a bridge between innate and acquired immunity by initiating specific cellular and humoral immune responses.

Dendritic cells use their branching “limbs” to feel the local environment for intruding antigens. They physically carry this antigenic information to local lymph nodes for processing and subsequent activation of the whole body’s lymphoid immune system. Thus dendritic cells and the lymphoid system interact to create an intricate web of communication from locally exposed cells outward to the far reaches of the body.

Dendritic cells have retained many pattern recognition receptors of the ancient immune system and have the unique ability to sense stimulations such as tissue damage and necrosis as well as bacterial and viral infections. These pattern recognition receptors are encoded in the germ line of each animal, and they are passed from generation to generation – perhaps one of the reasons dog breeding lines seem to inherit their parents’ immune capability, whether good or bad.

Other Systems With Immune Function

In addition to the blood and lymphatic systems, all organ systems are involved, in one way or another, in the function of the immune system, and all are likewise affected – positively or negatively – by the animal’s ability (or inability) to mount an appropriate immune response. There are, however, some organ systems that are especially prevalent in the immune response.

• Normal flora. The normal, healthy animal literally teems with bugs. It’s been said that there are many times more bugs on and in a healthy animal than the total number of cells that animal has in its entire body.

As an example, each square centimeter of healthy (human) skin contains 10,000 to 100,000 bugs! And, depending on where the sample is collected, a persistent bug counter will find anywhere from 100,000 to 1,000,000,000,000 bugs in each gram of intestinal contents. These good-guy bacteria produce many biochemicals that destroy other, pathogenic bacteria.

• Skin. Everyone knows that a dog’s skin, the largest organ of his body, acts as a physical barrier. But is also contains intrinsic factors that enhance his overall immunity. We’ve already seen that skin is replete with good-guy bugs. In addition, hair follicles produce sebum, an oily substance that contains lactic acid and fatty acids, both of which inhibit growth of some pathogenic bacteria and fungi.

Too-frequent bathing or persistent use of antibiotic-type soaps can destroy the natural immune function of the skin by drying it (opening pores and minute skin cracks to invasion of bacteria), eliminating beneficial bugs, and removing the protective layers of oils and acids.

• Mucosal barriers. The inner linings of several organs – the gastrointestinal tract, lungs, urethra, and urinary bladder, as examples – are lined with a thick and tenacious layer of mucus that traps (and may kill) foreign bodies, including microorganisms.

• Gastrointestinal tract. From its beginning to its endpoint, the gastrointestinal tract is actively involved in the animal’s immune functions. Lysozymes in the saliva (and also occurring in healthy tears) can break down the walls of some bacteria. The normally acidic environment of the stomach is an effective barrier to many incoming germs. The lining of the intestinal tract is also coated with mucus, another effective way to prevent the invasion of microorganisms.

As discussed above, an extremely important component of the gut’s immune function is the presence of the normal flora, the naturally occurring bugs of the gut.

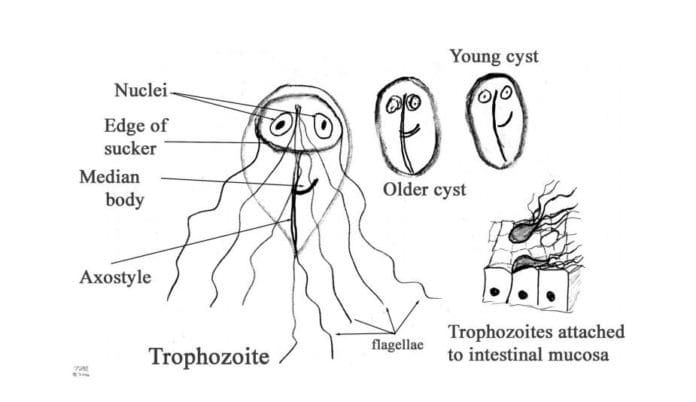

Finally, the gut is a prime source of lymphocytes, containing more of these immune cells than any other part of the body. This accumulation of lymph cells is collectively called GALT, for “gut associated lymphoid tissue.” GALT begins with the lymphoid tonsils in the throat and is further expressed by large patches of lymphoid tissues, called Peyer’s patches, that are located along many areas of the intestinal tract. The job of GALT is to recognize incoming foreign particles that may be harmful.

• Lungs. The innate and first line of defense of the lungs includes the germ-trapping mucosal lining of the inner lung walls along with tiny hairs whose ciliary action, along with sneezing and coughing, ejects living and nonliving things. Dendritic cells are also an active component of the lung’s immune system, along with a healthy population of white blood cells and immunoactive cells in the epithelial lining.

It is interesting to note that some of the immune pathways of the lungs are activated by mechanical stretching, further adding to the notion that exercise is healthy for the immune system.

• Liver. The liver is another prime site for immune function, and it is healthily supplied with lymphoid tissues as well as liver macrophages (Kupffer’s cells).

The liver is also a prime organ for processing and eliminating all sorts of toxins, and its antitoxic abilities are crucial for the health of the animal’s immune system. In light of this, it is interesting to note that the most common cause for withdrawal of drugs from the human pharmaceutical market is drug-induced liver injury (often referred to as DILI).

Drugs can be either directly toxic to liver cells, or they can adversely affect the liver’s immune function. This latter reaction may not show up until days or weeks after the beginning of drug use, and it is easy to miss the connection. According to one report, in humans DILI accounts for more than 50 percent of acute liver failure!

• Hormones. Many, if not all, of the hormones of the body have either a direct or indirect effect on the immune system. Of particular interest are the thyroid and sex hormones.

Many practitioners feel that the thyroid is the master gland of the body. The thyroid can also be easily affected by outside influences – one of interest to holistic practitioners is that vaccines and/or the preservatives in vaccines have been linked to thyroid dysfunction.

The overall capability of the immune system may also be adversely affected by sex hormones, and particularly the female sex hormones. Autoimmune problems such as diabetes, lupus, hypothyroid, and rheumatoid arthritis are much more common in females than males.

Immune System Disruptions in Dogs

There are several ways normal immune function can be disrupted or inhibited. The following are some of the most common.

Many diseases, especially those caused by viruses, can directly attack the cells of the immune system. Or they can be more insidious and slowly infiltrate one or more components of the immune system and ultimately cause diminished effectiveness.

Stress, especially if it is prolonged and if the animal can’t avoid it, can eventually overwhelm the ability of the immune system to respond, ultimately leading to increased susceptibility to disease. However, some stress is good for the body and soul, rather like working the immune-muscles to make them stronger.

An interesting study recently demonstrated that short-term moderate stress to animals (two hours of restraint) enhanced the immune response of the skin. This response was measured to be two to four times more robust than a normal response, it occurred quicker than normal, and it remained strong for weeks to months after the stress had ended.

“We believe that in many situations of acute stress, the body prepares the immune system for challenges such as wounds or infections,” says Firdaus Dhabhar, one of the study’s coauthors. “The immune system may respond to warning signals (such as stress hormones) that the brain sends out during stress. These prepare the body to deal with the consequences of stress.”

While antibiotics can help the immune system by decreasing the numbers of pathogenic bacteria, they can also destroy much of the animal’s protective mechanisms by killing the good-guy bugs that normally inhabit the gut, the skin, and other parts of the body.

Corticosteroids may be used to inhibit a hyperactive immune process, but excessive or prolonged use may inhibit the system to the point that it is no longer functional.

Vaccines are meant to stimulate the immune system so that it will be able to mount a later attack against the specific disease the vaccine is directed against. Problems with vaccines occur when the immune stimulation is too much for the animal to handle. This may cause anaphylaxis – a rare but immediate hypersensitive reaction that can be life-threatening.

More commonly (at least in the minds of holistic practitioners), the repeated introduction of vaccine antigens, along with the presence of modified viruses shed into the environment, may provide the final insult that exceeds the immunological tolerance threshold of some individuals. These individuals may exhibit any number of immune-related diseases, including arthritis, inflammatory bowel disease, cystitis, and skin conditions.

Immune System Diseases Affecting Dogs

Most holistic practitioners (including me) feel that nearly all diseases have a direct link to an imbalance of the immune system, and those that aren’t directly involved eventually have an adverse effect on the system. There are some diseases that are known for their involvement with the immune system, and these can be loosely divided into those where the system is hyperactive or where it is hypoactive.

Anaphylaxis is the term used to describe any acute, systemic manifestation of the hyperactive interaction of an antigen as it binds to an antibody. (This is also termed a Type I reaction, and it is typically the result of IgG immunoglobulins triggering a reaction with mast cells and basophils.) Possible causes include stinging and biting insects, vaccines, drugs of any kind, food substances, and blood products (transfusion from an improperly matched blood type, for example).

Clinical signs of anaphylaxis include restlessness and excitement, itch, edema, salivation, tearing, vomiting, abdominal pain, diarrhea, difficult breathing, shock, convulsions, collapse, and possibly death. Unlike other animals that typically have severe respiratory signs, the organ that is primarily affected in the dog is the liver; gastrointestinal signs rather than respiratory signs are more apt to be seen in dogs.

Anaphylactic shock and total collapse can be the result. Or more focal reactions may occur, including hives, itching, and facial swelling, especially around the eyes. Other diseases considered to be anaphylactic or Type I reactions include allergic rhinitis, chronic allergic bronchitis, allergic asthma (less common in animals than in man), food allergies, and atopic dermatitis, a chronic itchy skin disorder.

Other immune-related diseases are related to the self-production of antibodies that are toxic to various cells within the animal’s own body – a classic case of the immune system not being able to recognize “self.” The inciting agent for the self-against-self reaction is not always evident, but often appears to be related to drugs or to an oversupply of antigens from outside sources (vaccines).

The most common diseases in this category (also termed Type II reactions) include the complex of autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) and autoimmune thrombocytopenia. In general, autoimmune skin disorders fall into the various “pemphigoid” conditions.

Myasthenia gravis is a rare disease that causes extreme muscular weakness. Its symptoms are the result of autoantibodies that are directed against receptors that energize muscle activity.

Another way the immune system can run amok is by producing immune antigen/antibody complexes that are deposited in various areas of the body. These complexes interfere with normal function, and symptoms depend on the area affected. Examples of these (Type III) reactions include canine rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and glomerulonephritis (a kidney disease).

A final category of hyperactive immune diseases (Type IV reactions) activates the cell-mediated portion of immunity. Diseases in this category include contact sensitivity, autoimmune thyroiditis, and keratitis sicca.

At the other end of the spectrum, the hypoactive immune system, there are several diseases that result in poor immune performance. The most common of these result from infection with various viruses – for example, canine distemper, parvovirus infections in dogs and cats, and AIDS in humans.

Maintaining A Healthy Immune System

Maintaining immune health is a matter of trying to keep the whole of the system in balance with itself as well as in balance with the animal as a whole. Following are some general (and user-friendly) ways to help balance the immune system:

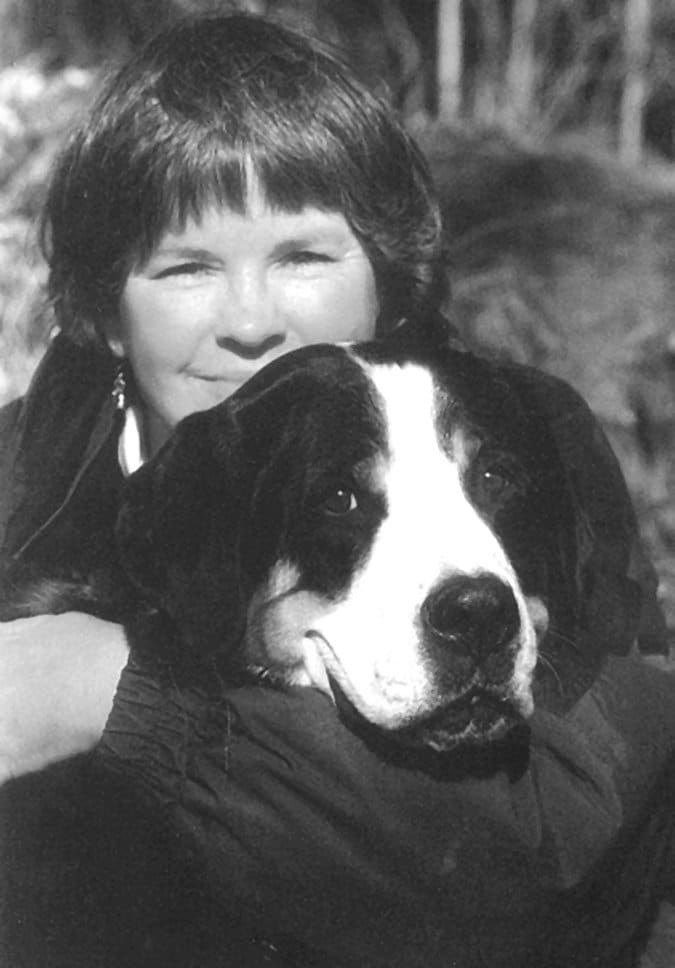

• Massage and exercise. The easiest and most enjoyable way to enhance your dog’s immune system is to put your hands to fur. Massage has been proven to increase lymphocyte numbers and to enhance lymphocyte function. The relaxation that comes with a good massage is good for emotional health, which has also been proven to be good for the immune system. The best part of massage is that it benefits the giver as well as the receiver; you enhance your own immune system as you help your best buddy enhance his or hers.

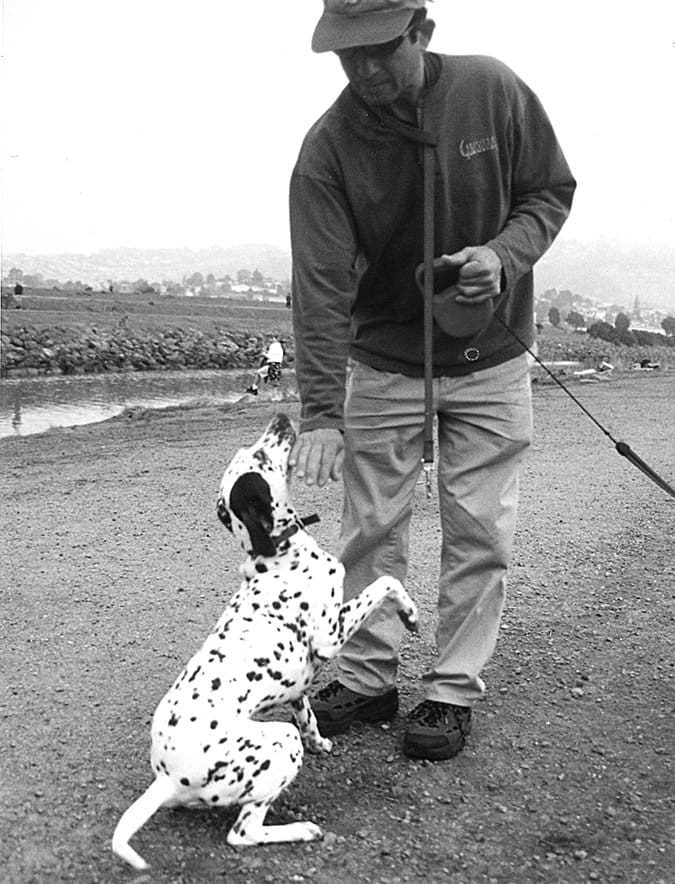

Exercise is another easy-to-implement activity that has proven, direct benefits for the immune system. In addition, the muscle activity helps cleanse the body of toxins and helps to move important components of immunity from one part of the body to another.

You don’t have to be overstructured about massage or exercise. Simply rub your best buddy in a way you’d like to be rubbed, and take a daily walk or romp in the park.

• Nutrition. The immune system demands good nutrition. Conversely, a diet deficit in any of the necessary nutrients will almost certainly cause immune-related disease. Specific nutrients that are indicated for immune-system health include: vitamins A (beta-carotene), C, E, and B-6; zinc; selenium; linoleic acid; and lutein.

Many of the above nutrients are high in antioxidant activity, and this may be the reason they are immune-supportive. Herbs and unprocessed vegetables are also excellent sources of antioxidant activity. It is interesting to note that recent studies have shown that the effects of antioxidants is much more profound when they come from a natural source rather than in the form of a pill or capsule.

• Herbs. Some herbs demonstrate a direct immune-enhancing activity. In most cases this enhancement actually balances immune function rather than being purely stimulating. For example, when given as the ground-up parts of the entire (fresh or dried) plant, echinacea has been shown to increase lymphocyte numbers when they are abnormally low, thanks to one of several biochemicals it contains. The same plant contains another biochemical that actually decreases the lymphocytes when their numbers are abnormally high.

Many herbs, ounce for ounce, have as much or more antioxidant activity than that found in vitamins A, C, and E. Herbs can be given on a daily basis, in the form of a pinch of fresh or dried herb sprinkled over your dog’s food or a mild tea made from the herb and poured over his food.

• Alternative medicines. Acupuncture is said to enhance the flow of chi, that immeasurable energy that flows throughout the body. It is thus a balancing medicine, and as it balances all parts of the body, it likewise helps to balance and enhance immune function.

Homeopathy works by enhancing what homeopaths refer to as the vital force, again by helping to balance this immeasurable vital force throughout the body. Many homeopaths equate the vital force to the immune system; its actions are similar, if not the same, as an intact and healthy immune system.

Flower essences and aromatherapy have been shown to enhance an animal’s immune function. It is likely these two work by modulating emotions which in turn enables the mind/body connection to ease the immune system into more optimal performance.

Dr. Randy Kidd earned his DVM degree from Ohio State University and his PhD in Pathology/Clinical Pathology from Kansas State University. A past president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, he’s author of Dr. Kidd’s Guide to Herbal Dog Care and Dr. Kidd’s Guide toHerbal Cat Care.