If you share your life with dogs long enough, chances are you’ll be tasked with the need to administer ear drops for dogs to treat mites or bacterial and fungal ear infections. Some of us are blessed with profoundly patient dogs who easily tolerate the experience in exchange for a tasty morsel and our heartfelt affection. Other dogs are certain ear drops are to be avoided at all cost.

In a perfect world, we’d all take the time to teach our dogs to calmly and cooperatively accept medically necessary handling long before such handling was necessary. In the real world, we often find ourselves scrambling to manage the situation as best as possible, with varying degrees of success.

Some people feel the only option is to increase the level of restraint needed to get the job done. This seems like the “easy answer” (at least for the human) in the short term, but it’s important to remember it will likely make things worse in the long run as the dog comes to associate the already unpleasant (to her) event with the added stress of intense physical restraint. Plus, who wants to knowingly distress their dog?

Fortunately, the following six steps can help teach your dog to more calmly accept ear drops for dogs, even when the lessons are taught in conjunction with actual ear drop application.

Giving Ear Drops to Your Dog

For many dogs, simply seeing the medication bottle sends them packing. If the bottle comes out only when we intend to use it, and our dogs find the experience unpleasant, who can blame them for wanting to suddenly become invisible? Dogs are masters at learning our behavior patterns.

Instead of tending to the bottle only when it’s time to apply medicated drops or ear wash, make a point to handle the bottle multiple times per day. Set the drops on the counter and toss your dog several small treats. She might be suspicious and ignore the treats at first. That’s fine. Act like you didn’t notice and busy yourself in the kitchen, ignoring both the medication bottle and your dog.

When she eats the treats, casually move the bottle to a new (still visible) location and toss more treats. If the medication keeps at room temperature, leave the bottle out to remind you to do this multiple times per day, even changing locations throughout the house. If it has to be refrigerated, leave yourself a note or set a reminder on your phone.

Be totally nonchalant about what you’re doing, and most importantly, practice separately from the time when you actually need to apply the solution.

If (or when) the sight of the bottle is not a source of worry for your dog, or better yet, her eyes light up at the thought of the yummy treats to come, practice a similar exercise by holding the bottle in one hand while offering treats. If your dog has a nose-touch targeting behavior, present the bottom of the bottle and ask her to “touch” it in order to earn a treat. Again, practice often, separate from actual application sessions.

Break Down the Ear Drop Application Process

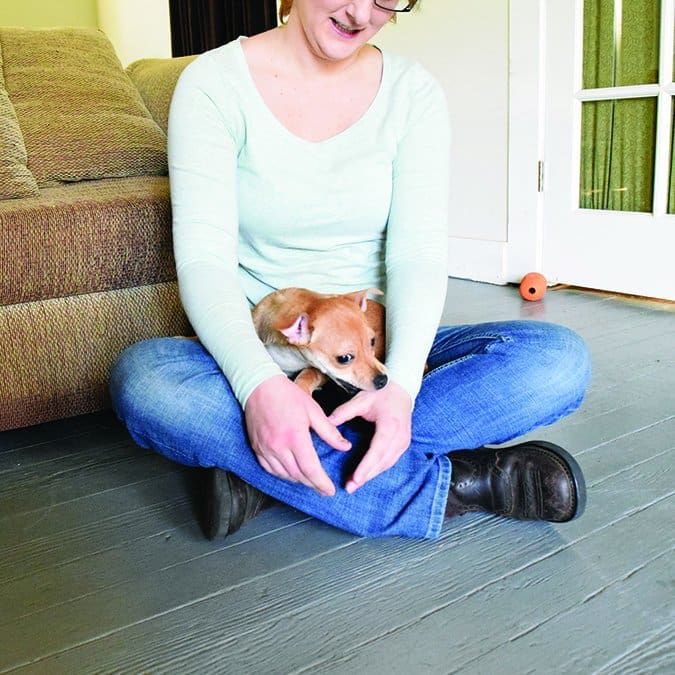

In teaching your dog to willingly participate in any husbandry behavior, the key is to break the desired behavior into several manageable pieces. Administering ear drops for dogs requires reaching for and touching the ear, lifting the flap (in dogs with droopy ears), exposing the upper end of the ear canal, juggling a medication bottle, and correctly aiming the nozzle – all before any solution even hits the ear!

Heavily rewarding your dog for each of the following steps can make the experience less stressful for everyone involved, while changing your dog’s emotional response for the better, which supports long-term training goals. Individual steps might include:

1. Investigate the ear.

With a bowl of tasty treats within arm’s reach, ask your dog to sit, and reach for her ear. The target behavior is your dog remaining in a sit as your hand makes contact with her ear. If she seems unfazed, mark (using a clicker, or a short verbal marker such as “Yes!” or “Good!”) as your hand makes brief contact, then deliver a treat. Repeat three to five times.

If your dog shies away as you reach for her ear, break this step into even smaller, easier steps. An easier step might be reaching toward, but not actually touching the ear, or touching the ear with one finger rather than your whole hand. Your goal is to find the version of the behavior that allows your dog to think, “That’s it? Wow. That’s easy!” Advance to the next step only when your dog seems completely comfortable with the easier behavior. Don’t worry; it usually goes faster than you’d think.

If your dog remains relaxed while you touch the ear, progress to reaching for the ear and lifting the flap to expose the underside and inner ear. Mark and reward your dog’s calm acceptance of this brief behavior. Repeat three to five times. Next, reach for the ear, lift the flap, and briefly manipulate the ear as you would to gain better access to the ear canal. Mark and reward. Repeat three to five times.

2. Add the solution bottle.

If all is going well, repeat the previous steps, this time while holding the closed bottle in your hand. Remember to mark and reward each step along the way, even though it seems “easy” for your dog. That’s the point! If your dog seems reluctant with a step, back up and repeat easier steps for a few more repetitions.

3. Simulate solution application.

Actually dispensing ear drops or ear wash solution for dogs requires concentrated focus on the task at hand. It’s common to struggle to accurately aim the nozzle, fumble around in the process, tense up, and hold your breath as you work. Rather than initially pairing your own awkwardness with a shocking squirt of fluid, make tolerance for your behavior its own rewardable step for your dog. Go through all of the motions necessary to administer the ear drops, but leave the cap on the bottle. Mark, reward, and repeat.

4. Administer the drops.

By now, your dog should be thinking, “Hey, this isn’t so bad,” since she’s been rewarded handsomely for several small, easy steps along the way. Now you’re ready to administer the drops.

Approach this step just as you did during the simulated application step; the only difference should be the gentle squeeze of solution. Mark and immediately offer a jackpot of several small treats dispensed one at a time.

If your dog seems especially bothered by a squirt of solution, try soaking a cotton ball and let the solution trickle into the ear from the cotton ball, versus a “squirt” from a bottle. If your ear product needs to be refrigerated, ask your vet if a dose can be safely brought to room temperature first for a less shocking experience.

5. You’re almost done!

With the drops safely in place, it might be tempting to call it quits, but rather than end the session on the most difficult step, it’s wise to quickly run through the easier steps in reverse order, continuing to reward your dog along the way. To further stack the deck in your favor, make a point to follow eardrop sessions with one of your dog’s favorite activities such as mealtime, a walk, or a rousing game of tug or fetch.

6. Practice, practice, practice!

While the short-term goal is to successfully get the ear solution into the ear with as little fuss as possible, the long-term goal is to teach your dog to willingly cooperate in the process. To that end, remember to practice often, not just when it’s time to actually administer medication. Working your way through all but the final application step, several times a day, will go a long way toward improving your dog’s opinion of this often-necessary husbandry behavior.

Try keeping the solution bottle and treats handy when you watch television; challenge yourself to run through the practice steps during each commercial break. A one-hour show will provide at least three quick opportunities for training!

As with many things, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. It’s always a good idea to proactively teach our dogs to be comfortable with the many forms of handling they are likely to experience while in our care. At the same time, it’s never too late to break necessary behaviors into smaller pieces in an effort to reduce stress and increase cooperation with our canine friends.

Stephanie Colman is a writer and dog trainer in Southern California.