Download the Full November 2017 Issue PDF

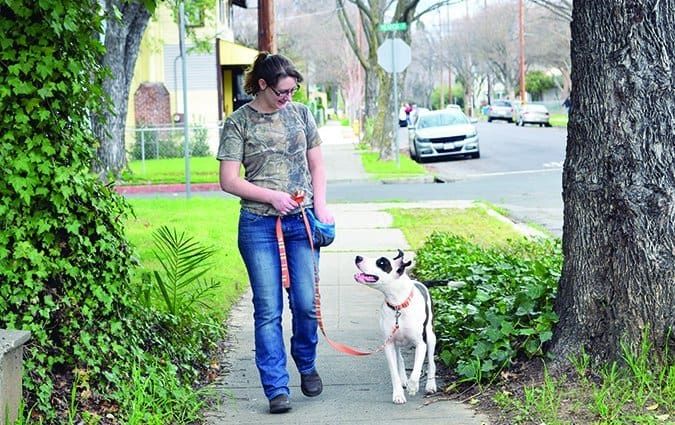

Walking the Dog on Leash – Why Is It So Hard for People?

After spending a couple days in the heavily dog-populated San Francisco Bay area recently, I found myself wondering: Why is it so hard for people to walk their dogs on a leash?

Dogs are so numerous in that area that I’d estimate I saw at least 300 human/dog pairs or groups out walking. (I had my young dog Woody with me, and so I was out walking him, too. And on the last day there, I picked up my son’s dog, Cole, and we stopped at a large, well-known off-leash area for dogs, Point Isabel, where one can observe at least 100 dogs at any given time of day.) I’d guess that a full 85 percent of the dogs I saw were either pulling or dragging their owners down the street. About half of these pulled steadily (“Come ON, let’s GO!”), and the other half pulled intermittently (“Wait, I need to sniff this! Okay, let’s go! Wait! I need to sniff that! Okay, let’s go!”).

Of the 15 percent of dogs I saw who were not pulling, about 10 percent were old, super slo-mo dogs who looked like they couldn’t (or just really didn’t want to) go faster than their human could walk. A few of these were being pulled by their owners – and that’s quite a sad sight in my book, an owner hurrying an old dog faster than he or she wants to/can go. I can’t help but wish the same fate to those people – having a distracted attendant rush them down facility halls when they are old and stiff and perhaps a little blind and/or deaf. Sheesh!

I’d guess that only about five percent of the dogs I saw being walked behaved nicely on leash: no pulling, no extended sniffing sessions, no stopping to bristle or bark at other dogs or people, just quietly matching their pace to their human’s pace, stopping and waiting quietly when the person stopped.

It’s a tragedy, because (of course) if it’s a big hassle or chore (or scary) to walk your dog, then he’s not going to get walked enough, and the less he walks, the harder it’s going to be to keep his cooperation on walks. Although I deplore their use, I see why people resort to choke chains, pinch collars, and even shock collars; the reason I deplore them, mainly, is that they rarely work. The pulling/reactive behavior persists (and sometimes worsens), because the person still doesn’t know how to teach the dog to walk nicely on leash; he or she just has a bit more control over the dog’s pulling/lunging etc.

Personally, I think the key to teaching a dog to walk nicely on leash is to start with tons of walking OFF-leash – and I know that I’m spoiled in this regard, in that I have tons of space in which to walk my dogs off leash safely. When your dog can walk nicely with you without a leash, then walking on leash is easy.

Here are a couple of past articles we’ve published on walking your dog. And I’m going to assign a few writers to write some more.

Leash-Training Your Dog for Crowds

Please Have an Emergency Evacuation Plan for Your Family (Pets and Humans)

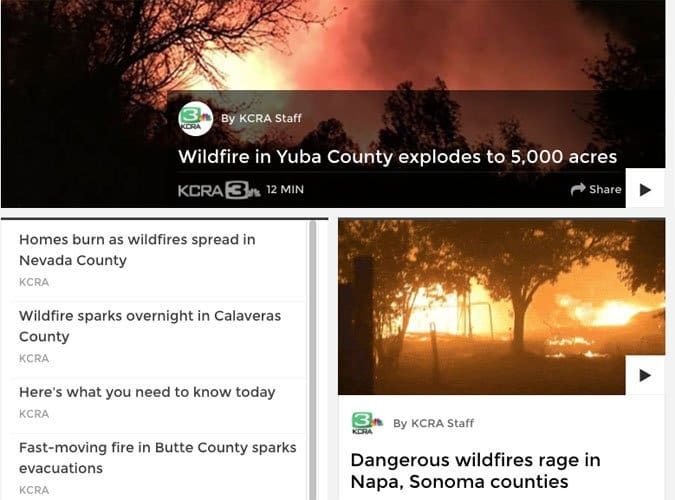

This past week, we’ve had some terribly windy days. In the wee hours of Monday morning, I woke up to a strong smell of smoke in the air. I stepped outside; the odor was strong but I couldn’t hear sirens nor see the glow of a fire anywhere. I turned on my computer, and was immediately able to find news about the source of the smoke: a wildfire had broken out about 10 miles north of my town. Another was burning about 20 miles to the east. My town was safe – but oh my word, there were also enormous fires burning 100 miles away, in the heavily populated areas of Napa and Sonoma Counties. And the wind was still gusting at 50 and 60 miles per hour, spreading burning embers far, wide, and fast.

As I type, tens of thousands of people have had to evacuate their homes and businesses, and hundreds of homes and businesses have burned to the ground. Thank goodness, I’m seeing reports from dozens of friends and acquaintances from that area, reporting on Facebook that they were able to get themselves and their human and small animal family members out of the burning areas safely. But I am aware that there are lots of family farms and horse boarding facilities in the area that’s burning – even a tourist attraction called Safari West, which has zebras, giraffes, rhinos, cheetahs, and other African animals on the property. I shudder to think about all the large animals in that area who can’t be evacuated quickly or easily.

This, as well as the hurricane-related disasters that have struck the Gulf states in recent months, has underlined for me the importance of having an emergency plan in place to protect and evacuate my family. What would I do if I had only minutes to leave my house? What would I grab?

What would I do if I had a little more time – if my area was on an emergency evacuation warning, as it was back in February of this year, when part of the infrastructure of the enormous dam I live downstream from started showing signs of failure?

In the former case, I’d need only some leashes, a cat carrier, the dogs and cats, my husband, and maybe that little emergency radio we got when we pledged a donation to our local public radio station that time. It can run on batteries, solar power, or be wound up by hand; it can even help charge a mobile phone (of course, I’d grab my cell phone, too). I had better dig it out of the kitchen cabinet and put it on that shelf by the front door.

I’ve already had practice with the latter case -with hours and even days to get ready. When the broken spillway at the Oroville (California) Dam caused erosion that threatened to undermine the massive structure itself, local officials had advised residents to be ready to evacuate if needed. My husband and I spent the better part of a day packing up family photos, legal documents, passports, computer backup drives, veterinary records, and other possessions into big plastic storage boxes, and stored them in a friend’s barn, upstream and uphill from any potential flood. I had dog leashes and food in my car . . . but then I made the mistake of leaving town (to care for some evacuated animals!) and was 20 miles away when the actual evacuation order came. It took over an hour of panicked calls and texts to reach my husband and make sure he grabbed the animals and got out of town safely (I wrote about that event here). My new rule: Don’t get separated when a potential disaster is at hand!

Anyway, with this new disaster so close and so fresh in my mind, would you indulge me? Won’t you take a couple of minutes and think about what you would do if you had to evacuate your home with only a couple of minutes’ notice? And then, make another plan for an evacuation if you had a couple of hours’ notice?

Here are some good resources online for disaster planning:

https://www.ready.gov/evacuating-yourself-and-your-family

https://www.ready.gov/make-a-plan

https://www.asecurelife.com/emergency-evacuation-plan/

One of those crazy loose-dog days

This morning, I was talking to my husband, while standing in the doorway of his office, which is located in a little outbuilding behind our home. I was watching my dogs Otto and Woody, as they stood with their backs to me, looking alertly at something through the chain-link fence that separates our backyard from the front yard. Suddenly, Otto lifted his head and let out a howl of frustration (it’s more like the noise that Chewbacca the Wookie from Star Wars makes) and quick as a wink, Woody neatly lifted his nose, unlatching the gate, and both dogs pushed though the gate and ran into the front yard after something.

Obviously, I abruptly left the conversation with my husband, yelled “Hey! Come!” and ran in the direction of my dogs. To their credit, both of them ran back toward me, gaily and immediately, but looking over their shoulders at a little dog, who looked like a Shih Tzu-mix and who was standing, loose, uncollared, and unaccompanied, at the foot of my driveway. When the dog saw me, he started trotting down the sidewalk.

I didn’t see any person around, and didn’t recognize the dog, so I ran back into my house, grabbed my treat pouch and a leash, told the dogs to STAY (this, because of Woody’s apparently newly learned trick with the gate latch), and trotted down the sidewalk myself in pursuit of the stray dog.

I spent about 10 minutes trying to catch the dog with no success. I didn’t want to frighten him into a panicked run; he looked more or less like he knew where he was going, but he wasn’t interested in approaching me, or even eating one of the delicious treats I tossed toward him. When he realized at one point that I was trying to maneuver him into a yard where I might be able to corner him, he took off at a faster pace, and I stayed back, so he slowed to a walk again. If I had my cell phone with me, I would have called to see if an animal control officer was available to help me corral the dog, but I hadn’t grabbed it when I ran to get a leash. I told myself that he’d be okay, and hoped he’d find his way home.

Then I walked my dogs to my office, which is located in another house, about two blocks away. I put on a pot of coffee, and had just sat down at my computer, when Woody, who likes to sit on a loveseat I have in the front window of the house, just behind my desk chair, started growling at something outside the window. His growl alerted Otto, who jumped on the couch, looked out the window, and let out another Wookie sound. So I looked out the window, and there is a stray dog standing in the front yard, looking back at my grumbling dogs – not the stray from earlier, though! This one was a medium-sized, brown and white Cattle Dog-mix, with no collar. Jeez Louise!

I grabbed my treats and a leash again, and went out the front door. This dog immediately approached me, as if we were old friends. Hi, Buddy! I fed him a few treats as I eased a leash around his neck, and led him to my fenced backyard. Then I went in the house and called animal control. They said they would send an officer to come scan the dog for a microchip and, if he didn’t have one, take him to the shelter.

About 15 minutes later, I see an animal control truck driving down the alley across from my office. I thought he was looking for my house, so I went out my front door and yelled, “Hey Peter!” (having recognized the officer from volunteering at the shelter). He leaned out the truck window and yelled back at me, “Did you lose the dog you caught?” I looked over my shoulder, saw the dog I caught still in my backyard, and yelled back, “No! He’s right here!”

Peter got out of his truck and was saying, “As I was driving up your street, I saw a small black and white Cattle Dog . . . .” when we both, at the same time, saw two big, brown Labradors (or maybe Chesapeakes?) come trotting down the sidewalk between us. What the???

Peter crouched down and called to the dogs, and one came right to him, with a big genial grin. I ducked back into my house, grabbed a leash and some treats, and dashed back outside again. I couldn’t see the other brown dog anywhere – she had VANISHED. Crap!

Peter said, “Well, there is an address and phone numbers on this dog’s collar; he lives on the next street over.” I said, “Tell you what, I’ll call the numbers and take him home if you want to grab the dog out of my backyard. Or chase the other Lab. Or look for the black and white Cattle dog!” I clipped a leash onto the friendly dog’s collar, and started walking him back toward my house, where I had left my car that morning, and which was on the way to his house. As I walked, I called the numbers on the dog’s collar and left messages saying I had the dog (his tag said his name was Ezekial), and was going to bring him home, but that Ezekial had been with another dog who had gotten away.

As I was driving, my phone buzzed with an incoming text from Peter. It said, “The dog in your yard has a microchip.” Hurray!

When I got to the address on the dog’s collar, thank goodness, there was a gentleman in the front yard waiting for me. He told me that the dogs sometimes get out and they usually head down to the river and go for a swim. He said, “I’ll throw Zeke in the car and go look at Riverbend Park for Bella. That’s where they usually turn up!”

I was literally one house away from my office when I saw the black and white Cattle Dog that Peter had pursued earlier, wandering down the sidewalk. No collar. I texted Peter and told him I would keep the dog in sight if he could come and help me try to catch the dog. I didn’t get a response, and guessed (correctly, as it turned out) that he was in pursuit of some other dog somewhere else. I followed the dog for about 15 minutes. I got ahead of him three times, and tried to subtly herd him into a yard where I could contain him until help could arrive, but he clearly understood what I was trying to do and just kept taking off at a run. Finally, I got a text from Peter saying he wouldn’t be able to help any time soon – he had his hands full with a situation back at the shelter – and I gave up. The Cattle Dog was very street-savvy; hopefully he’d end up wherever he had come from.

Five loose dogs within an hour and a half. One with a collar and tags, safely returned to his owner. I just called the shelter to check; the one I caught who had a microchip was already in the process of being returned to his owner. I wish all the luck in the world to the other three, none of whom wore collars (though, who knows, maybe they had microchips). And now I have to go find a chain and a snap to put on the gate that my own dog has learned to open.

Have you ever had one of those mornings?

Have You Made Arrangements for Your Dogs (In Case Something Happens to You)?

Hello, and sorry I’ve not posted for a few weeks. Our publishing headquarters staff ran some older blog posts in place of fresh content from me, as I took a couple of weeks off for surgery – yikes!

Long story short: I had my first-ever routine colonoscopy, and it found a large mass! Crazy, because I had no symptoms of any sort of digestive, elimination, or any other health problem. But the surgeon said it had to be removed, along with the 10 or so inches of colon and small intestine it was attached to. So, the day after I shipped the October issue of WDJ to the printer in early September, I had laparoscopic abdominal surgery, and spent six days in the hospital. I got fantastic news regarding the mass on the day I was discharged: the thing was benign, so no further treatment will be needed.

Fortunately, I had a couple of weeks between the colonoscopy and surgery to figure out what to do with my dogs, both while I was in the hospital and after I came home, so they wouldn’t be going crazy for a lack of walks (and so Woody wouldn’t be jumping on me as I lay on the sofa, as he is wont to do). My husband was home, but he had a too-full workload and would also be waiting on me, so sending the dogs away made the most sense.

My sister and her husband, who have three very small dogs and one small/medium-sized one, took in my 70-pound senior dog, Otto. Three of their dogs are terrier-mixes and have the same sort of scruffy faces that Otto has; he looks like a zoomed-in version of them. Given how much I have fostered dogs and puppies over the years, and how weary Otto has grown of having rude guest dogs in his home, one might imagine that he wouldn’t like staying with four small barky dogs – but actually, he seems to adopt an entirely different persona there.

At home, he plays the elder statesman, too dignified to romp or wrestle with other dogs, and quick to nip any canine nonsense from Woody and other dogs in the bud – the classic “fun police” behavior. But at my sister’s house, he instigates all sorts of play! He wrestles and rolls around like mad with the little guys, especially the newest member of the pack, a nine-pound, perhaps three-year-old former stray named Lucky. My sister said that Otto grabs toys and initiates games of “chase me” with Lucky, something I haven’t seen him do for years with any other dog.

Also, he’s never, ever, slept on my bed. I have nothing against dogs sleeping on beds, I just personally don’t like dog hair on my bed, nor waking up uncomfortable because the dog is taking up all the room. At my sister’s house, he helped himself to the queen-sized, elevated bed in the guest bedroom, and slept with his head on the pillows!

My 25-year-old son took my almost-two-year-old dog Woody for a couple of weeks. An athlete himself, my son is the best candidate for giving Woody enough exercise to keep him out of trouble. Woody also gets along well with my son’s dog, Cole, an all-black Black and Tan Coonhound, and my son’s roommates, who are also athletes and also love dogs. At one point during their stay together, my son took Woody on a weekend retreat to the mountains with his sports team, comprised of twenty-something twenty-and thirty-something guys, all of whom love dogs. Woody swam and hiked and played fetch until he collapsed in happiness. When my son brought Woody home to me, about two weeks after my surgery, after a brief period of excitement, he rested quietly with me for days! He was tired!

I am very lucky to have family who are ready and willing to help with my dogs, and who would even keep my dogs for the rest of their lives if something happened to me – and I know this because I asked! I don’t take this for granted; I’ve seen many dogs at my local shelter who were brought there by friends or relatives of the dogs’ deceased owners. That thought is just torture for me.

My husband and I have been talking for years about how we need to write wills and set up a trust, so whichever one of us survives the other and/or our children can avoid probate while settling our affairs – but we haven’t yet done anything about it. This episode prompted me to renew my advance healthcare directive and start taking notes about a will and a trust. No one who knows me will be surprised to learn that most of what I have on paper so far concerns the dogs.

Frequent WDJ contributor CJ Puotinen wrote a terrific article on arranging for your pets’ care after your own death. I’m reviewing it as I take notes. Check it out here.

Teach Your Dog to Choose Things

Our dogs have very little opportunity for choice in their lives in today’s world. We tell them when to eat, when to play, when to potty, when and where to sleep. We expect them to walk politely on leash without exploring the rich and fascinating world around them, and want them to lie quietly on the floor for much of the day. Compare this to the lives dogs used to live, running around the farm, chasing squirrels at will, eating and rolling in deer poop, chewing on sticks, digging in the mud, swimming in the pond, following the tractor…

There’s a good likelihood that this lack of choice is at least partly responsible for the amount of stress we are seeing in many of our canine companions these days. Imagine how stressed you would be if your life was as tightly controlled as your dog’s! We can introduce choice to our dogs by teaching them a “You Choose” cue: Select a very high-value and very low-value treat. Show one to your dog and name it (Meat, Beef, Chicken). Let her eat it. Repeat several times. Show the other to your dog and name it (Kibble, Milkbone). Let her eat it. Repeat several times. Now tell her to “Wait,” say your high-value name, put it in a bowl and set it on the floor at your feet. Repeat “Wait” if needed, say your low-value name, put it in a bowl and set it on the floor six inches to the side of the first bowl. Now say “You choose!” “Pick one!” (or whatever you want your “Choice” cue to be) and invite her to choose a bowl. While she eats that treat, pick up the other bowl. Repeat numerous times, randomly putting down high-value/low value first, on random sides, until it’s clear she’s realizing she can choose her preference. (You might be surprised to discover what you think is higher value for her; it may not be!) Now think of other ways you can offer your dog choices in her daily life!

Laser Therapy Treatments for Arthritic Dogs

ALTERNATIVE PAIN MANAGEMENT FOR ARTHRITIS: OVERVIEW

1. If your dog has chronic arthritis pain – especially if he’s relatively young for such troubles – consider exploring some of these alternative options.

2. Look for a veterinary practitioner who is open to alternative technologies. Many have developed a preference for a certain tool, based on good results with previous clients.

Arthritis pain, which affects four out of five older dogs, interferes with everything that makes life special for our best friends. Wouldn’t it be great if we could turn the clock back?

Technology may not yet offer a time machine, but it can seem that way for dogs treated with modern therapies that make them feel like puppies again. Would laser treatments, shock wave therapy, Pulsed Electromagnetic Frequency therapy, or other innovative treatments help your dog jump onto the sofa or run and play the way she used to?

Veterinary Lasers

Once exotic, laser treatments have gone mainstream with equipment that is increasingly safe and effective, so that thousands of veterinary clinics treat dogs, cats, horses, and other animals with lasers for a variety of conditions.

The term “laser” was originally an acronym for Light Amplification of Stimulated Emission of Radiation. First developed in the 1960s, lasers are used in fiber optics, computers, military weapons systems, manufacturing, building construction, communications, and medicine.

Laser beams are monochromatic (existing within a narrow band of wavelengths), coherent (tightly aligned), and collimated (with photons traveling in parallel). Lasers vary according to wavelength and power, and some lasers emit pulsing rather than continuous light waves. Power is measured in joules, an electrical energy classification.

Laser equipment varies according to the energy a laser emits (measured in joules); the time it takes the energy to reach target tissue (which determines the length of the treatment); wavelength (the laser’s depth of penetration, with blue light superficial, red light deeper, and nonvisible light deeper still); frequency (the number of impulses emitted per second); power (watts, the rate at which the energy is delivered); emission mode (continuous or pulsing); and dosage (joules per square centimeter, or J/cm2).

Class 1 and 2 lasers, which include laser pointers, are generally considered safe but have limited therapeutic use. Class 3 lasers (type 3A emits visible light and type 3B emits nonvisible light) have some therapeutic uses. The most recent laser classification (Class 4), approved for medical use by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2005, is used in human and veterinary medicine to improve circulation, relax muscles, and reduce inflammation, pain, and swelling caused by injuries, surgery, or chronic conditions, such as arthritis.

LLLT, or Low Level Laser Therapy, is performed with “cold” or “soft” lasers, which penetrate the skin’s surface with minimal heating. According to the research group ColdLasers.org, which describes over 40 therapeutic lasers, some class 4 cold lasers will warm the treatment area but are not considered hot lasers because they cannot cut or cauterize tissue.

The plethora of technical terms and conflicting claims can confuse clients and veterinarians alike. In a February 2016 report in the journal Vetted, Jennifer L. Wardlaw, DVM, asked, “Should your veterinary practice become laser-focused?” She recommended comparing the wavelength, power density, and pulse modulation of lasers, not just their cost. “For example,” she wrote, “if you get a weak laser with a small diode, it may take 45 minutes to treat a 5-centimeter surgical incision with the correct dosage of 4 to 6 J/cm2. But if you get a more powerful laser with a bigger diode, it may only take you five minutes to treat the same patient.”

Dr. Wardlaw recommends starting canine arthritis treatments with 6 to 8 J/cm2 every other day for two weeks. For wound healing she prescribes 8 J/cm2 once per day for seven days, and for tendonitis 6 J/cm2 every other day for two weeks. A hand-held wand delivers the treatment (goggles or sunglasses protect the eyes of practitioners and patients) and the dosage can be applied with a sweeping motion or by using back-and-forth movements as though following a grid while treating one small area at a time.

In 2011, clinicians at the University of Florida’s Small Animal Hospital compared 17 dogs with intervertebral disc disease treated postoperatively with lasers to 17 dogs not treated with lasers. All of the dogs (mostly Dachshunds, a breed associated with intervertebral disc disease) were unable to walk, and their diagnoses were confirmed through MRI or CT scanning. All underwent decompressive surgery after their diagnoses.

Thomas Schubert, DVM, and William Draper, DVM, treated half of the study’s 34 dogs with Thor Photomedicine’s Class 3B laser (thorvetlaser.com) in the near-infrared range, a wavelength that has been shown to speed the healing of muscle pain and superficial wounds in humans. They presented their findings at the American College of Veterinary Internal Medicine’s 2011 meeting in Denver, calling the results “amazing” because the laser-treated patients walked sooner, avoided medical complications, were less stressed, and reduced their recovery expenses due to less hospitalization time.

Success with Laser Treatment on Dogs

Tia Nelson, DVM, at Valley Veterinary Hospital in Helena, Montana, has used the K-Laser, a popular Class 4 device, to treat more than a hundred dogs for pain and wound healing. “The initial protocol is six treatments over three weeks,” she explains, “typically three the first week, two the second, and one the third, then as needed after that, usually once a month. The results vary, depending on the condition’s severity, location, and cause along with the dog’s age and activity levels, but most dogs seem to be more comfortable for many weeks after the initial treatments and some don’t need additional therapy.”

Dr. Nelson keeps track of her clients’ anecdotal reports. “Typically, we hear about dogs now being able to scramble happily up and down the stairs,” she says, “and generally being more active and engaged with their families.”

One of Dr. Nelson’s favorite patients is a Pomeranian who stopped jumping on the bed to sleep with her owner due to lower back arthritis. “Pain meds weren’t helping,” she says, “and joint-protecting supplements offered minimal relief. The owner was somewhat skeptical but agreed to try the K-Laser treatments. She called me almost in tears of joy after the first week’s treatments because her little girl was able to jump up on the bed!”

The website of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association lists 280 member veterinarians who provide laser therapy, and more can be found with simple online searches.

Lasers Designed for Home Use?

There are no clinical trials in the medical literature testing lasers designed for home use, but if you look for them, you can find people who have bought portable low-level lasers and who report good results on themselves and on their pets. You can find portable Low Level Laser Therapy equipment ranging in price from $119 to $299, as well as units that are more expensive, on sites such as Amazon.

Some lasers that are used for pain relief are marketed as beauty products for wrinkle reduction and other cosmetic effects because their distributors cannot promote them as medical devices. Customer support, refund policies, and product warranties vary, so check with manufacturers for details, and take online customer reviews with a grain of salt.

One might take comfort from marketing claims that products are “FDA cleared,” “FDA approved,” or “FDA registered.” Please note, however, that these are not official endorsements. A manufacturer registered with the FDA has completed an application informing the FDA of its products and is thus “FDA registered.” A medical device that is “FDA cleared” is “substantially equivalent” to a device already on the market. “FDA approval” means only that the FDA has reviewed the manufacturer’s testing results and has concluded that the benefits of the product outweigh its risks.

At Muller Veterinary Hospital’s Canine Rehabilitation Center in Walnut Creek, California, Erin Troy, DVM, has worked with canine patients who did not appear to benefit from home laser devices. “But they did respond when treated with Low Level Laser Therapy using a proven effective laser used by someone knowledgeable about what settings to use and where to treat,” she says. “I’m frustrated with home devices because there is much more to laser therapy than point-and-push-the-button.”

These are early days in veterinary laser treatments, and the few articles published about them in the medical literature caution that more blinded, placebo-controlled clinical trials are needed before the use of lasers is routinely advocated, especially for conditions other than pain, inflammation, and wound healing. If you are considering the purchase of a Low Level Laser for using on your dog at home, we’d suggest finding a veterinarian who uses and is knowledgeable about lasers, and who will show you how best to select and use a therapeutic laser at home.

Red Light Therapy for Arthritis Treatment

Also known as photonic therapy, low-intensity light therapy, LED therapy, photobiostimulation, photobiomodulation, and photorejuvenation, the application of red light by means of a hand-held device, stationary panels containing LED lights, or units designed for treatment from a distance or in direct contact with the skin all claim to reduce inflammation and arthritis pain in pets and people. You can find a dozen or more different models online.

Red light therapy uses wavelengths of light between 620 nm and 700 nm, with the most popular wavelengths used in in-home products between 630 nm and 660 nm. Some devices include multiple wavelengths.

The most popular red light device may be the $270 Tendlite, which resembles a slender flashlight powered by a rechargeable battery that emits red light at 660 nm. The Tendlite is held 1 inch from the area to be treated for 1 minute at a time. (Most red light therapy devices require longer treatment times.)

For additional information about red light therapy and red light devices, see Red Light Therapy Guide, Red Light Man, and Photonic Health, which focuses on red light therapy for dogs, cats, and other animals.

Shock Wave Therapy

It sounds electric, but shock wave therapy is actually the application of high-energy sound waves to specific parts of the body, such as to break up kidney stones and gallstones without the need for invasive surgery. For 25 years, ESWT (Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy, which refers to the waves’ generation outside the body) has been used to treat orthopedic conditions and joint pain in humans, horses, and dogs.

The canine conditions shown to improve with ESWT include osteoarthritis, hip and elbow dysplasia, chronic back pain, osteochondrosis lesions, sesamoiditis (degeneration of small bones in the foot that causes persistent lameness, especially in racing Greyhounds and Rottweilers), tendon injuries, lick granulomas, cruciate ligament injuries, nonunion or delayed-healing bone fractures, and painful scar tissue.

Shock wave therapy for dogs can have impressive results. Straus was contacted by New Jersey resident Debbie Efron when her veterinarian, Charles Schenck, DVM, a past president of the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association, recommended shock wave therapy for Taylor, Efron’s 12-year-old Labrador Retriever, who had arthritis in her hips, spinal column, and right hock, and who had just torn a ligament in her right knee. Efron had never heard of shock wave therapy and asked for Straus’s opinion.

Encouraged by the positive results Straus found in the medical literature, Efron scheduled the procedure. Dr. Schenck treated Taylor’s hips, hock, and knee in two sessions, three to four weeks apart. He did not recommend shock wave therapy for the spine; he felt it works better where there is more soft tissue, so he continued treating the spine with acupuncture. Dr. Schenck hoped that eventually Taylor would experience an 80 percent improvement lasting six to seven months.

Just a few days after the first treatment, Efron told Straus, “Taylor is greeting me at the door with a toy in her mouth, something she stopped doing weeks ago. She is eager to go for walks and pulls me around the block with no limping and her back legs no longer buckle. She is playful again, wanting to wrestle and play.”

Eight months after treatment, Efron sent an update: “Taylor is on no medications, but she gets a lot of supplements and a raw diet. I think her improvement peaked about eight weeks after the second treatment, and she’s been great on walks ever since.”

As Kristin Kirkby, DVM, wrote in “Shock Wave Therapy as a Treatment Option” in the August 2013 Clinician’s Brief, “Shock waves can be generated in many ways, but electrohydraulic devices have the greatest capacity to produce and project high energy to a deep focal depth. ESWT can be highly focused and can achieve a focal point beyond 10 centimeters into deeper tissues, depending on the treatment head used. ESWT differs from radial pressure wave therapy, which does not deliver focused energy at the target; instead, acoustic waves spread eccentrically from the applicator tip.”

According to Dr. Kirkby, shock wave therapy has been shown to modulate the osteoarthritic disease process in animal models. Several studies have demonstrated positive results in joint range of motion and peak vertical force – as measured using force plate analysis – in dogs with stifle, hip, and elbow arthritis. For example, in dogs with unilateral elbow osteoarthritis treated with ESWT, improvement in lameness and peak vertical force was equivalent to that expected with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

A dog may be shaved to reduce interference between the probe and the dog’s skin, and a gel is applied to improve transmission. Treatment time depends on the amount of energy delivered and number of locations treated. A common dose of 800 pulses per joint requires fewer than 4 minutes to deliver.

The first shock wave generators were expensive, bulky, noisy, and painful, but the technology keeps improving. The new PiezoWave2 Vet Unit uses piezoelectric crystals to produce high-pressure sound waves and it has made ESWT machinery smaller, more affordable, and more accessible for large and small animals to receive treatment without sedation. TRT’s VetGold device is now also smaller and almost pain-free, no anesthesia required.

The makers of the VersaTron 4 Paws and the newer, smaller ProPulse shock wave devices publish case studies online, including reports of arthritic inflammatory disease, shoulder and elbow arthritis, and lumbar spondylosis in Labrador Retrievers and other dogs. In several cases, a variety of conventional and alternative therapies had been tried with minimal success, and the dogs were in severe chronic pain. In some cases lameness increased after the first treatment, but most dogs experienced significant improvement within a week.

Because shock wave therapy does not cure or reverse arthritis, its relief of symptoms may diminish after several months or a year, at which time a repeat treatment may be needed.

Ultrasound Therapy for Pain Reduction

Best known as a diagnostic tool or a means of determining an unborn baby’s sex, ultrasound has been used by physical therapists since the 1940s to alleviate pain and inflammation. Sound waves generated by a piezoelectric effect caused by the vibration of crystals in the head of a wand or probe pass through the skin and vibrate adjacent tissues.

In addition to having a warming effect, ultrasound has been shown to increase tissue relaxation, local blood flow, and scar tissue breakdown. Conditions treated with ultrasound include tendonitis, joint swelling, and muscle spasms. The treatment is not recommended on or around malignant tumors or metal implants.

In March 2008, a critical review of published research on the effects of ultrasound in the treatment and management of osteoarthritis in humans appeared in the Journal of the Canadian Chiropractic Association. Seventeen articles met the researchers’ criteria for methodology and accurate reporting; most of them showed that ultrasound, in addition to being cost-effective, portable, and easy to use, has significant therapeutic benefits.

For information about veterinary ultrasound therapy and referrals to veterinarians who treat dogs for arthritis and other conditions with this approach, contact the American Association of Rehabilitation Veterinarians or the Canine Rehabilitation Institute, or simply search online for veterinary ultrasound therapy.

Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy (PEMF)

Magnets have long been thought to have healing properties, and whole industries have been created around the alleged benefits of magnetic jewelry, massage tools, mattress pads, and other devices. Do they work? A lack of research on the application of magnets to human or canine illnesses or injuries makes it hard to know.

But when it comes to pulsed electromagnetic field therapy, or PEMF, the evidence is growing. For many years electromagnetic field therapy was widely used in Europe while its use in the United States was restricted to animals. Veterinarians treating racehorses for broken bones were the first American health professionals to use PEMF. Now thousands of human clinical trials have shown beneficial results from PEMF therapy for chronic low back pain, fibromyalgia, cervical osteoarthritis, osteoarthritis of the knee, lateral epicondylitis, recovery from arthroscopic knee surgery, recovery from interbody lumbar fusions, persistent rotator cuff tendonitis, and other conditions.

The first PEMF device was a coil that generated a magnetic field into which the patient’s body was placed to deliver treatment. Most of today’s PEMF devices are mats similar to thick yoga mats containing flat spiral coils that produce an even electromagnetic field, or they consist of rings or coils that are placed on or under the person or animal being treated, or they are flat, circular magnets that can be placed under a mattress. An electric-frequency generator energizes the coils to create a “pulsed” electromagnetic field.

Comparing PEMF devices by their technical specifications requires a crash course in frequency, amplitude, intensity, sine waves, sawtooth wave forms, Schumann resonance frequencies, and other terms – and even the technically informed disagree as to which combinations are best for human, canine, and equine health. Intensity is measured in Tesla units (µT) and frequency is measured in Herz units (Hz). Those who compare PEMF systems usually recommend staying close to the earth’s magnetic field frequencies (11.75 and 11.79 Hz, or in the 0 to 30 Hz range) and low intensity (1 to 20 microtesla, which is less than the earth’s 30-66 microtesla).

Most of the websites mentioned here provide technical information and reports that help users understand the basics.

PEMF devices can be used for acute and chronic conditions, and there are no known adverse side effects, potential drug interactions, or interactions with surgical implants. The electromagnetic field penetrates clothing, fur, casts, and bandages to reach all tissue in the target area.

Acute inflammation often improves after one or two treatments, while chronic or degenerative symptoms may need two weeks or a month. In most cases, pain medications can be reduced or eliminated. (This should be done under medical supervision.)

Thanks to PEMF’s popularity in Europe, low-intensity, low-frequency, full-body PEMF mats are available in the United States. They are designed for humans but some users report improvements in dogs and cats recovering from accidents or illness, including arthritis in older animals. Pets often seek out and sleep on PEMF devices.

The best full-body mats are expensive, with the iMRS, which is made in Switzerland, starting at $3,600, and the Bemer, which is manufactured in Liechtenstein, starting at $4,300. Both can be rented by the month.

PEMF for Pets

In addition to full-body mats for people, the PEMF marketplace offers products specifically for dogs, cats, horses, and other animals. See the American Holistic Veterinary Medical Association website for veterinarians who provide pulsating magnet therapy.

Originally designed for human use, the Assisi Loop is sold by Assisi Animal Health for use with pets. According to its manufacturer, “The Assisi Loop generates a twice-per-second 2-millisecond burst of a 27.12 Megahertz radio wave signal with an amplitude of 4 microtesla. This pulse-modulated field is non-thermal and non-invasive, yet is sufficient in strength to have therapeutic benefit.”

The Loop’s electromagnetic field extends 4 to 5 inches on either side of the coil. The Assisi Loop website explains, “By emitting a burst of micro current electricity, a field is created which evenly penetrates both soft and hard body tissue around the target area. This electromagnetic field causes a chemical cascade, which activates the well-known nitric oxide cycle. Nitric oxide is a key molecule in healing for humans and animals. The compound is released when we exercise, and when we are injured, for the body to naturally repair itself.”

The Assisi Loop comes in two sizes, 7.5 inches (20 centimeters) or 4 inches (10 cm). The smaller loop is convenient for treating extremities, small animals, or conditions that are focused in an area less than 4 inches in diameter. For chronic or degenerative conditions like arthritis, the manufacturer recommends giving dogs three or four 15-minute treatments per day for a week to 10 days, monitoring until you see improved mobility and less pain response. You can then taper down to one or two treatments per day or even one to three treatments per week, and over time the patient may be treated only as needed for pain.

Both sizes of the Assisi Loop offer a minimum of 150 15-minute treatments and the Assisi Loop 2.0 Auto-Cycle offers a minimum of 100 15-minute treatments. The life of the Loop depends on its battery, which, because of FDA regulations, cannot be recharged or replaced. One Assisi Loop typically lasts from three weeks to six months, depending on the condition being treated and the number of treatments required per day.

The Assisi Loop can be purchased ($280) from veterinarians and animal rehabilitation facilities or directly from Assisi Animal Health with a prescription from your veterinarian.

Magna Wave sells several professional PEMF devices for between $7,000 and $21,000, plus a Magna Wave LP (Low Power) model, which is recommended for bone and soft-tissue injuries, for $429. According to its manufacturer, the Magna Wave LP incorporates Inductively Coupled Electrical Stimulation (ICES) technology that penetrates beneath the skin’s surface and zeros in on affected deep-tissue areas. Magna Wave provides PEMF training, practitioner certification, and technical/business support for veterinarians and other health care professionals.

EarthPulse PEMF consists of a circular magnet that goes under your (or your dog’s) mattress, by itself or in combination with a second magnet. The magnets plug into a simple control unit and can be left running without supervision for up to 12 hours. Its adjustable amplitude settings, recovery mode, and sleep programs make the EarthPulse a versatile, portable, “set it and forget it” PEMF device. Its five systems range in price from $499 for the basic single-magnet model to $1,799 for the four-magnet battery operated unit recommended for horses.

The Bio-Pulse Dog Therapy System consists of a large (for dogs over 50 pounds) or small (up to 50 pounds) mat with magnetic coils mounted on soft foam. “The depth of field of Respond Systems Bio-Pulse PEMF Therapy System can penetrate through the entire body of a dog lying on the bed reaching deep into the joints and muscles, stimulating circulation,” explains the website. “The system can be placed on the couch, in a crate, under your animal’s bedding or even in the car.” Prices range from $599 to $899.

The only PEMF system that’s designed to be worn by dogs is Brandenburg Equine Therapy‘s SI (Sports Innovations) Canine PEMF Therapy Blanket. It comes in three sizes (small, medium, and large) and is recommended for recovery, pain management, increased circulation, vitalization, and general relaxation. Another option is the PEMF dog mat, which can be placed on any sleeping surface. The therapy blankets and mats, which are made in Germany, cost $1,650 each and can be rented.

The Amethyst BioMat

Who wouldn’t want to rest on a bed of amethyst crystals? Add gentle heat produced by far infrared technology and the relaxing benefits of negative ions, and you have a spa experience – one that your dog can enjoy, too.

BioMats, manufactured in South Korea where the technology is popular and well researched, are known for their anti-inflammatory effects, providing relief from sprains, strains, muscle and joint pain, stiffness, stress, and fatigue. BioMats come in several sizes, starting with the BioMat Mini (17 by 33 inches, 8 pounds, $670 plus $40 shipping). The mat is sewn with channels containing alternating rows of amethyst and tourmaline crystals, known among crystal enthusiasts for their healing properties.

For years I kept a BioMat Mini on our sofa, turned to the lowest heat setting. Chloe, my Labrador Retriever, ignored it because she preferred to sleep with her head on a frozen water bottle. But with age, her preferences changed, and by her 10th birthday, Chloe was spending a few hours every day stretched out on the sofa. Many BioMat users report that, like Chloe, their dogs went from stiff and sore to more relaxed and mobile soon after they started resting on the mat.

Creature Comforts

As our dogs age, we do everything we can to make them comfortable. In addition to nutrition, exercise, weight management, natural and prescription pain medications, aromatherapy, medicinal herbs, and assistive devices, today’s technologies may provide the support that will make a difference for your older dog.

Montana resident CJ Puotinen is the author of The Encyclopedia of Natural Pet Care and other books.

Are Canines Cognitive?

COGNITIVE LEARNING FOR DOGS: OVERVIEW

1. Get cognitive with your dog. Check out the possibilities and play with the ones that appeal to you.

2. Find a dog training professional in your area who offers classes or instruction in canine cognition learning.

3. Give your dog opportunities to make choices and observe his selections; you might learn something about him that you never knew!

There was a time, centuries ago, when scientists and philosophers told us that animals don’t feel pain. Of course, we know now how wrong and cruel that was, and I doubt there’s a Whole Dog Journal reader out there who would try to argue that dogs don’t feel pain.

Then we were told that humans are the only species that make and use tools. Oops, wrong again. A quick online search on “Animals, Tools” finds multiple intriguing articles and videos about a multitude of various animals that make and use tools, including insects, birds, mammals, and more.

Next, we were warned that if we credited “human” emotions to non-human animals we were engaging in anthropomorphism, defined as “the attribution of human traits, emotions, and intentions to non-human entities.” It’s now pretty widely accepted that many other animals, including dogs, share much the same range of emotions that we do, and in fact that it’s pretty arrogant of us to claim them as “human” emotions. Think about it. Can your dog be happy? Sad? Frightened? Worried? Those are emotions.

In our apparently endless quest to prove our species superior to all others who walk this earth, even as those other dominoes fall, we have long clung stubbornly to the belief that dogs and other species were seriously deficient in the cognition arena. Defined as “perception, reasoning, understanding, intelligence, awareness, insight, comprehension, apprehension, discernment” (and more, depending on the source), cognition also includes the ability to grasp and apply concepts, and “theory of mind” – the ability to recognize and understand the thoughts of others.

Academic Discoveries in the Cognitive Ability of Dogs

Fifteen years ago, you wouldn’t have found the words “canine” and “cognition” in the same sentence. Today, following on the heels of a blossoming interest in animal cognition in the field of behavioral science, there are canine cognition researchers and laboratories springing up all over the world. Among the most notable: Adam Miklosi’s “Family Dog Project” at Eötvös Loránd University, in Budapest, Hungary; the Horowitz Dog Cognition Lab at Barnard College in New York City (with Julie Hecht and Alexandra Horowitz); the Clever Dog Lab at the University of Vienna, in Austria (Zsofia Viranyi and Friederike Range); and the Duke Canine Cognition Center at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina (Brian Hare).

You can find a more complete list of Canine Cognition research centers at Patricia McConnell’s blog on the subject. Suffice it to say, it’s happening all over the place.

So what does this mean for the regular dog owner? The knowledge gained and shared by canine cognition researchers can inspire your local forward-thinking dog training and behavior professionals to introduce new and interesting activities in their dog training programs.

You can also access a growing body of information that can lead you to fascinating things you can do with your own dog in the comfort of your own home. Brian Hare, PhD, who co-authored The Genius of Dogs with his wife, Vanessa Woods, created the citizen science Dognition program, which offers a cognition assessment tool for your dog and a new cognition game you can do with your dog each month. (See “The Dog’s Mind,” May 2013.) Our new and growing understanding of canine cognition can move the entire dog training profession toward a more enriched world that better meets the needs of our canine companions.

Early Cognition Fun

Here at Peaceable Paws (my training center in Fairplay, Maryland), we have been following the canine cognition revolution with great interest. One of the first glimmers of a practical application of our dogs’ cognitive abilities came with Claudia Fugazza’s “Do As I Do” protocol. Studying under Adam Miklosi in Hungary, Fugazza developed a protocol to teach dogs to imitate human behavior – something it was previously believed dogs weren’t capable of doing. We started offering “Copy That” workshops, and delighted in seeing dogs master the art of imitation.

The training world has also embraced the cognitive concept of choice for our canine pals. (See “Training A Dog to Make Choices,” November 2016.) To quote psychology professor Dr. Susan Friedman, “The power to control one’s own outcomes is essential to behavioral health.” Acknowledging that dogs often have very little choice in their lives, trainers have begun teaching a “You choose” cue, encouraging clients to find more ways of offering their dogs a choice. Learn how to play “You Choose” here.

Discrimination Games for Building Canine Cognition

Many cognition games involve the concept of “discrimination” (selecting one designated object from other similar ones) and “fast mapping” (quickly learning the names of new things and being able to correctly identify them). The famous Border Collie Chaser knows the names of hundreds of different objects and is able to correctly select the one her handler asks for. Even more impressive, if a new object is placed with several that she already knows, when asked for the new object she can correctly select that one and bring it back, using “process of elimination” (she knows all the others and correctly surmises the new word must apply to the unknown object).

Here are some discrimination games you and your dog can play. In each case, we are asking her to grasp a concept – object names, shapes, colors – and apply that understanding to make correct choices:

Object Discrimination

1. Select two objects that your dog likes – a stuffed toy, a ball, a stick. If she already knows the names of the objects, you’re ahead of the game!

2. Name one object, offer it in your hand, pause, and then cue her to touch it with her nose or paw – ie. “Ball, touch!” When she does, click and treat. Repeat several times.

3. Now do the same with your second object – “Teddy, touch!” Click and treat.

4. Now offer both objects at the same time. In order to help her succeed, offer one closer to her, and cue her to touch that one. Repeat multiple times, randomly alternating which one you offer closer to her and ask her to touch. Also switch sides, so the same object isn’t always in the same hand.

5. Gradually decrease the offset of the target object until you can offer them both to her at the same distance, and she will consistently touch the one you ask her to touch.

6. Now repeat the process with the objects on the floor, again starting with the target object closer to her to help her succeed, until she can touch either requested object consistently and correctly with both objects the same distance away.

7. Finally, name and add more objects to her repertoire. The sky’s the limit!

Shape Discrimination

For this one, you will need to find or make shapes that are similar in size and color, with the shape being the only difference. We use black shape silhouettes (squares, circles, and triangles) glued onto square white boards.

1. As with the object discrimination game, hold up one shape, name it, and ask your dog to touch it, i.e., “Square, touch!” Repeat several times.

2. Now do the same with your second shape – “Circle, touch!”

3. Now offer both shapes at the same time. In order to help her succeed, offer one closer to her, and cue her to touch that one. Repeat multiple times, randomly alternating which one you offer closer to her and ask her to touch. Also switch sides, so the same shape isn’t always in the same hand.

4. Now repeat the process with the shapes on the floor, propped up against a wall, again starting with the target shape closer to her to help her succeed, until she can touch either requested shape consistently and correctly with both objects the same distance away.

5. Finally, name and add more shapes to her repertoire.

Color Discrimination

This one can be a little tricky, since dogs are red-green color-blind, like some humans. Blue looks like blue to them, yellow looks like yellow, and black looks like black. Greens and oranges also look “yellow-ish,” while reds look brown or tan. When we teach colors we use colored paper plates and start with blue and yellow, since we know dogs can distinguish those. We then use red for our third color, since whatever it looks like to the dog, we know it is different from blue or yellow. The process is essentially the same as the previous two discrimination exercises.

1. Hold up one color, name it, and ask your dog to touch it, i.e., “Blue, touch!” Repeat several times.

2. Now do the same with your second color – “Yellow, touch!”

3. Now offer both colors at the same time. In order to help her succeed, offer one closer to her, and cue her to touch that one. Repeat multiple times, randomly alternating which one you offer closer to her and ask her to touch. Also switch sides, so the same color isn’t always in the same hand.

4. Repeat the process with the colors on the floor, again starting with the target color closer to her to help her succeed, until she can touch either requested color consistently and correctly with both the same distance away.

5. Finally, name and add red to her repertoire.

And what then? You can get creative and mix them up. See if she can learn to select the red balls from a pile of red and blue ones. Teach her the names of the rooms in your house and ask her to bring the yellow Frisbee to you from the bedroom. Teach her the names of family members and ask her to take the blue teddy to Dad in the living room.

Reading, Writing, ‘Rithmetic

No fooling – taking cognition one step farther, it really is possible to teach dogs to read, count and even write. We’ve touched on canine reading before (See “Teaching Your Dog to Read,” October 2006), but here’s a quick rundown of how to start:

1. Make two white signs that are identical in size and shape, with the word “SIT” in large black letters on one sign, and the word “DOWN” on the other.

2. With your dog standing in front of you, hold up the “SIT” sign, pause, and verbally cue your dog to sit. Repeat until you can hold up the sign and he sits without you having to say “Sit.” He now thinks holding up a white square with black squiggles on it is a cue for “Sit.”

3. Now hold up the “DOWN” sign in the exact same position you previously held up the “SIT” sign, and verbally cue your dog to down. Repeat until you can hold up the sign and he lies down without you having to say “Down.” He now thinks holding up a white square with black squiggles is the cue for “Down.”

4. Now vary which sign you hold up in the exact same position, pause and cue the appropriate behavior, until you see that your dog is beginning to offer the correct behavior in response to whichever sign you hold up. Your dog is reading – if recognizing that one set of squiggles means he should sit, and the other means he should lay down.

5. If you want to take it further, make additional cue cards for behaviors your dog knows, and use the same procedure to teach him new words.

What about writing and arithmetic? Ken Ramirez, former head curator at the Chicago Aquarium and current Executive Vice President and Chief Training Officer of Karen Pryor Clicker Training, has taught his dog to count to 14. It’s too complicated to explain here, but you can read Ramirez’s description of the amazing project here.

Emily Larlham of Dogmantics Dog Training in San Diego, California, demonstrated her dog’s ability to write words with a marker held in his mouth to a dumbfounded crowd of dog trainers at last year’s Pet Professional Guild Summit in Tampa, Florida. I kid you not. There is still so much more to learn about our dog’s cognitive abilities. The sky truly is the limit.

Over-the-Counter Flea Medicine for Dogs

Last month, in “Bravecto, Nexgard, or Other: Which Oral Flea Control Should You Use?” we described the five oral medications that veterinarians may prescribe to stop or prevent a dog’s flea infestation. This month, we’ll describe the four oral medications that kill fleas on dogs and are available to owners as over-the-counter (OTC) products – no prescription necessary.

As with last month’s installment in this mini-series on flea-control options, the descriptions of these products should not be taken as a recommendation or endorsement. (For more about this, see “Panacea or Poison?” in this issue.)

These products are already purchased by dog owners by the millions. Our intent in describing them by chemical class is to inform owners how they work, and what dogs they are indicated for and, more importantly, contraindicated for. Contraindications are conditions under which something should never be used; in our experience, owners and veterinarians alike are often completely unaware that these ubiquitous medications shouldn’t be given to certain dogs.

This way, if your veterinarian recommends their use, or you somehow run across them, you’ll know what they are and whether or not they’re right for your dog. As you can see from the comments already generated below, these products incite real passion–for and, especially, against. Our purpose is to keep you informed so you can form better judgments…so please don’t assume Whole Dog Journal recommends these products just because we’re running this piece. We simply want to serve readers by telling you what’s out there.

A caveat: The dosages of the products discussed here cover a wide range of weights. A dog at the low end of the weight range indicated for either dose might receive five times as much medication as needed. If your dog is at the low end of the weight range, consider doing the math and splitting the chew or tablet to give your dog an effective dose that’s more appropriate for her size.

For example, the minimum dose of Capstar is 0.45 mg per pound of the dog’s body weight. A dog who weighs six pounds would need only 2.7 mg of nitenpyram. The smallest tablet of Capstar delivers 11.4 mg of nitenpyram. You could give the dog a quarter of a tablet (2.8 mg) with equal benefit and less risk.

Note: Last month, we said that we would discuss both OTC oral flea-killing medications, as well as prescription medications that help control fleas through the use of insect-growth regulators, in this article. Instead, we’ve broken these two topics into their own separate pieces. We will discuss the products containing insect-growth regulators in another issue.

Over-the-Counter Oral Flea-Killing Medications

| NAME | KILLS | CHEMICAL CLASS | ACTIVE INGRED. | FREQ. | MFR. STATEMENT | FDA APPROVED | MIN. AGE/ WEIGHT |

| CAPSTAR Elanco (888) 545-5973 |

Fleas | Neonicotinoid | Nitenpyram | Daily | >98% of fleas within 6 hours, starts killing fleas within 15 minutes | 2000 | 4 weeks; 2 lbs. |

| CAPGUARD Sentry (Perrigo) (800) 224-7387 |

Fleas | Neonicotinoid | Nitenpyram | Daily | >90% fleas within 4 hours, starts working within 30 minutes | 2014 | 4 weeks; 2 lbs. |

| FASTCAPS PetArmor (Perrigo) (800) 224-7387 |

Fleas | Neonicotinoid | Nitenpyram | Daily | “Kills fleas fast” | 2014 | 4 weeks; 2 lbs. |

| ADVANTUS Bayer (800) 422-9874 |

Fleas | Neonicotinoid | Imidacloprid | Daily | >96% of adult fleas within 4 hours, starts killing fleas within 1 hour | 2015 | 10 weeks; 4 lbs. |

Neonicotinoids

The oral flea-killing products that have been approved for OTC sale in the United States are in a class of chemicals called neonicotinoids.

Insects and mammals alike have nicotinic acetylcholine receptors (nAChRs) in the cells in their central nervous systems (mammals also contain these receptors in their peripheral nervous systems). Neonicotinoids bind to these receptors, overstimulating them to the point that they cause paralysis and death. The chemicals bind more strongly to insect neuron receptors than mammal neuron receptors, making them more toxic to insects than mammals. Neonicotinoids are widely used in agriculture to control insects.

Three of the four OTC oral flea-killing products on the market contain nitenpyram, a neonicotinoid chemical that gets rapidly absorbed into the dog’s bloodstream from his gastrointestinal tract, and clears rapidly, too. On average, the peak blood concentration is reached in one hour (range: 15 to 90 minutes) after administration, and the elimination half-life is about three hours. These products work fast, but only for about 24 hours; more than 90 percent of the nitenpyram is eliminated in the urine within one day in dogs.

Because they are so fast-acting and have such a short span of activity in the dog’s body, these medications are commonly used when a dog who is heavily flea-infested needs to be cleared of fleas fast – perhaps so he could be transported or kenneled without fear of introducing fleas into a previously flea-free environment. These products are also a good choice to eliminate fleas quickly, without leaving a pesticide on or in the dog’s body for weeks to come.

The fourth product contains imidacloprid, one of the most heavily used agricultural insecticides in the world. Imidacloprid has been used in the “spot on” topical flea-killing product Advantage since 1996. Imidacloprid is considered to be “low” in toxicity via dermal (skin) exposure, but moderately toxic when ingested, which makes its introduction in an oral product counter-intuitive. It, too, has a short half-life (2.2 hours) and reaches its peak blood concentration quickly – 1.3 hours.

1. Capstar, Capguard, and FastCaps

The active ingredient in all three of these products is nitenpyram; it’s included in each of the products in the same amount, so we will discuss all three together.

Because it’s so fast-acting, shelters and rescue groups have long used Capstar when they received an animal who was so heavily infested with fleas that handling, kenneling, or transporting the animal puts other animals at risk of infestation.

Each of the drugs comes in the form of a tablet, and each is offered in two dosage sizes: a tablet containing 11.4 mg of nitenpyram, meant for dogs weighing from two to 25 pounds, and a tablet containing 57 mg of nitenpyram, meant for dogs weighing from 25.1 to 125 pounds. The minimum dose is 1.0 mg/kg (0.45 mg/lb) of the dog’s body weight.

Adverse reactions that may occur in dogs include lethargy/depression, vomiting, itching, decreased appetite, diarrhea, hyperactivity, incoordination, trembling, seizures, panting, allergic reactions, including hives, vocalization, salivation, fever, and nervousness.

The frequency of serious signs, including neurologic signs and death, was greater in animals under two pounds of body weight, less than eight weeks of age, and/or reported to be in poor body condition. In some instances, birth defects and fetal/neonatal loss were reported after treatment of pregnant and/or lactating animals.

These products are said to be safe when used concurrently with other products, including heartworm preventatives, corticosteroids, antibiotics, vaccines, deworming medications, and other flea products.

2. advantus

Bayer Healthcare spells the name of this product with a small a. The product represents a very new application of imidacloprid – to our knowledge, the first oral use of imidacloprid as an insecticide for animals. The FDA granted Bayer a three-year period of marketing exclusivity from the date of its approval (in 2015).

Advantus does not contain any animal proteins, making it suitable for dogs with animal-protein food allergies.

The drug is delivered in the form of a soft chew. Bayer suggests that the ideal or target dose of imidacloprid is 0.34 mg/lb (0.75 mg/kg). Advantus is offered in two dosage sizes: a chew containing 7.5 mg of imidacloprid, meant for dogs weighing from four to 22 pounds, and a chew containing 37.5 mg of imidacloprid, meant for dogs weighing from 23 to 110 pounds.

Adverse reactions to advantus that may occur in dogs include vomiting, decreased appetite, decreased energy, soft stools, and difficulty walking.

Advantus is said to be safe when used concurrently with other products, including heartworm preventatives, corticosteroids, antibiotics, vaccines, and deworming medications.

A relatively small number of dogs and puppies are used in pre-approval studies to determine a product’s safety. For this reason, we’ve never encouraged dog owners to rush to try newly approved products; dogs owned by early adopters, in essence, become the next generation of test dogs. For this reason, and because this is the first drug to use imidacloprid in this way, we’d recommend holding off on buying or using this product until more is known about its safety.

Nancy Kerns is the editor of WDJ.

Panacea or Poison?

From the first issue, one of WDJ’s missions has been to bring you “in-depth information about effective holistic healthcare methods.” However, the word “holistic” is subjective, and it’s frequently used to mean very different things.

Many people use the phrase “holistic healthcare” when they, in fact, mean natural, alternative, or complementary healthcare. However, we use the phrase in its original sense – to mean “relating to or concerned with wholes or with complete systems.” We look for therapies and practitioners that offer the most benefit and do the least harm, whether it’s a conventional prescription medication or an organic essential oil, a veterinarian who specializes in oncology or one with advanced training in chiropractic. We don’t eschew vaccines – but we do advise using the least number needed to protect your dog. We don’t promote the use of unproven alternatives to heartworm preventatives – but we do offer explicit advice on how to minimize their use without leaving dogs vulnerable to heartworm infection.

And, to use a recent example, we don’t tell owners to refrain from ever using toxins on their dogs, but we do give them information about how to use toxins, such as the minimal use of topical pesticides and oral flea-killing medications, when less-toxic flea control has failed and the dog is suffering – and when the substance is not contraindicated.

Judging from the number of critical comments regarding September 2017’s article on prescription flea-killing medications, you might think we told our readers that the medications were terrific and should be given to every dog, every month, for life – no worries! Um, no. We think those medications should be reserved for last-resort use. But we’re also aware of cases where they can literally save lives – for example, with dogs who are severely allergic to fleas and who live in areas where fleas are a year-round pestilence. And if an owner is considering their use, she should know, as just one example, which products are likely to aggravate her dog’s epilepsy, and which products don’t pose that risk.

There are publications that denounce the use of most conventional veterinary medical practices and therapies, vaccines, heartworm preventatives, and pesticides included. There are others that impugn every sort of medicine that’s not conventional; they take an equally dim view of acupuncture, chiropractic, traditional herbal medicine, massage, and more. Please don’t confuse us with any of them. We’re committed to giving you solid information about all of the most beneficial options available to you.

Great Solutions for Dog Crate Problems

DOG CRATING ISSUES: WHAT YOU’LL LEARN

1. To evaluate your crating protocols and make any necessary changes (bedding? location? type of crate?) to ensure you are following best crating practices.

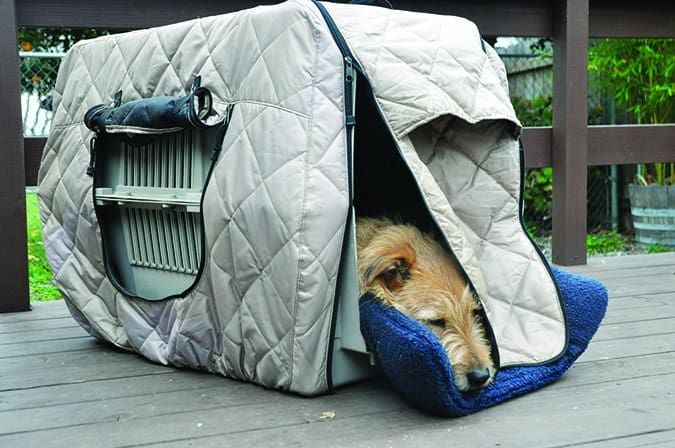

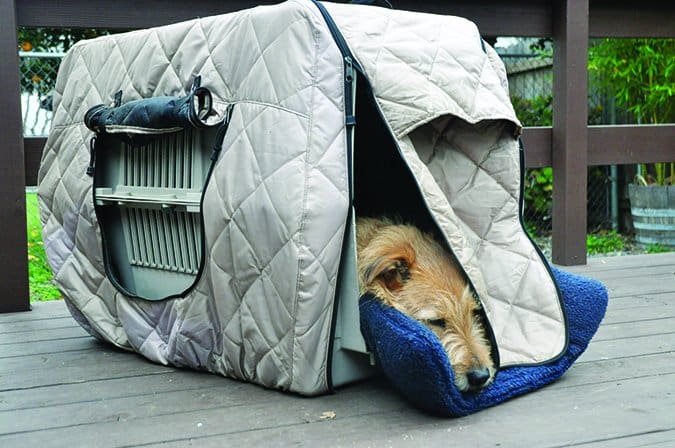

2. To help your dog learn to love his crate in case a time comes when he must be confined, for an extended stay at the vet, for example, or (dog forbid) an evacuation.

I first used a crate as a canine management tool in the early 1980s. I was a little skeptical of the concept (“Put my dog in a box? What?”), but within two days was completely convinced that this newly touted training tool had merit for both housetraining puppies and as a “safe space” for older dogs.

Decades have passed since then, and I continue to believe that crates are a valuable tool for successful dog keeping. However, I have also seen some crate abuses over the years that prompt me to add some important caveats to my usual encouragement of their use.

Excessive Crate Confinement

Overuse is probably the most common abuse of crates. I cringe when I hear of dogs who are routinely left crated 10 or more hours a day while their humans are away at work. And what if you get stuck in a major traffic back-up, or your boss decides to call a last-minute mandatory staff meeting?

I can’t think of a better way to wreck your dog’s housetraining than to crate him for excessive periods with no option but to soil his own den – not to mention the potential for creating severe anxiety by forcing him to eliminate in his bed against all his training and instincts. While your dog may be physically capable of going for 10-plus hours without soiling his crate, he shouldn’t have to. There is some evidence that over-crating may lead to kidney damage for dogs who routinely try to “hold it” longer than they should.

Some of us (me included) sometimes crate one of their dogs to prevent intra-family aggression. Using a baby gate to separate the dogs, instead, can keep peace in the family and reduce unnecessary confinement.

Solutions: Examine your crating practices. Do you have options other than crating? If your dog can’t have house freedom, will a baby gate or closed door serve the same management function while giving your dog more room to move and a choice to use his crate – or not? (He still shouldn’t be shut in his room for 10-plus hours a day! If he has to be regularly left home alone for long periods, find a reliable force-free dog walker to give him a daily break.)

If you’re not sure your dog can be trusted uncrated, start a testing protocol, gradually leaving him uncrated for increasing periods.

Improperly Introducing Your Dog to the Crate

Nothing is guaranteed to make your dog dislike his crate faster than being forced into it. If your dog shows resistance to crating, stop! Rather than shoving, try tossing high-value treats inside. If he still doesn’t go in voluntarily, find an alternative until you can take the time to teach him.

Solutions: Good breeders teach their pups to love crates, and an increasing number of shelters and rescue groups are making the effort to do the same with the dogs in their care. If not, and you’re bringing him home for the first time, try a harness and a seat belt or tether to safely restrain him for the trip. Or bring along a friend or family member who can hold him.

Once home, use counter-conditioning to convince your new canine companion that being near a crate makes wonderful things happen, and use shaping to operantly condition him to happily and willingly enter his new bedroom.

Crating a Dog as Punishment

Yikes! If forcing to crate is the best way to make your dog hate his crate, using the crate as punishment may be the next-best way. A cheerful time-out is okay – just to remove him from a difficult situation, but never an angry “Bad dog! Get in your crate!” Similarly, never punish him in his crate by banging on it or shaking it. And never, ever reach into his crate to drag him out and punish him. I don’t reach into my dogs’ crates for any reason; crates are their safe space and I respect that.

Solutions:The easy solution here is – just don’t. If you must crate your dog to give him (or you!) a cooling-off period, do it cheerfully, and give him something nice in the crate – yummy treats, a chewy, or a stuffed toy.

Unprotected Crating

You can accidentally give your dog a negative experience and association with the crate by crating him in a place where he is not protected from the unwanted attentions or proximity of others. If your dog isn’t fond of children and you crate him where children can harass him, he will feel trapped and stressed, and you are likely to make his association with children (as well as with his crate) infinitely more negative.

There can be a similar outcome if he has a tense relationship with another dog in your household and you crate him while the other dog is allowed to be free: Trapped and stressed, his relationship with that dog will likely worsen. If he’s crated in your vehicle and you have to swerve or stop suddenly, the crate bouncing around the back of your SUV is likely to convince him he’d rather not be crated.

Solutions: Always crate your dog in a location where he is protected from unwanted attentions from humans or other dogs. An exercise pen placed around the crate as an “airlock” may be adequate, or he may be better off crated in a separate room with a baby gate across or the door closed. Crates in a vehicle should always be secured so they can’t roll around if there is a sudden stop or worse, a collision.

Crating Tips

With all that said, you might think my ardor for crates has cooled. Far from it; I still think they are a fantastic dog management tool, when used properly. Here are some additional tips to help your dog get the most benefit from his crating experience:

1. If your dog has had past unpleasant experiences with crating, consider changes. If you were using an airline-style crate, try a wire crate. If he was crated in the living room, try the den. If he gets aroused by outside stimuli, move the crate away from the front door, to an isolated, quiet location in the house.

2. Make sure your dog’s crate is placed in an environmentally comfortable location. You may not realize that the sun hits the crate at some point in the day, causing your dog to overheat, or a draft from a vent that makes him uncomfortably cold. Try putting crates in different locations and see if he shows a preference.

3. Respect your dog’s bedding preferences. He may love a cushy comforter to lie on while crated, or he may prefer the coolness of a bare crate floor. Figure out what he likes and accommodate his wishes. If possible, try offering two crates with different types of flooring or bedding and see if he chooses one over the other.

4. While you work to shape your dog to voluntarily crate, try putting something wonderfully irresistible inside the crate (near the door at first) and closing the door, so he gets a little frustrated about trying to reach it. Then open the door so he can reach in and grab it. As he gets bolder about grabbing the item, gradually move it farther back so he has to go deeper in the crate to get it.

5. Consider giving your dog more spacious accommodations. When housetraining, we want the crate to be just large enough to stand up, turn around and lie down comfortably, so he can’t soil one end and rest comfortably in the other. After he is well housetrained, there is no need to keep him a small space – he can have a bigger crate if he likes.

So Why Even Crate?

Why bother to crate at all, especially once your dog is housetrained and past the puppy chewing stage? There are times when it can be very useful to be able to crate your dog. It is certainly safest to transport your dog in a vehicle if he is properly crated. Also, there comes a time in the lives of many dogs when they need to be on “restricted activity,” whether following surgery, or perhaps for a torn ACL, broken limb, or some other medical mishap.

A dog who is calm, relaxed, and even happy about being crated will endure these trying times far more easily than one who is stressed about his enforced confinement. Be a responsible crate practitioner, and your dog will be much happier for it.

Author Pat Miller, CBCC-KA, CPDT-KA, is WDJ’s Training Editor. Miller is also the author of many books on positive training. Her newest is, Beware of the Dog: Positive Solutions for Aggressive Behavior in Dogs.

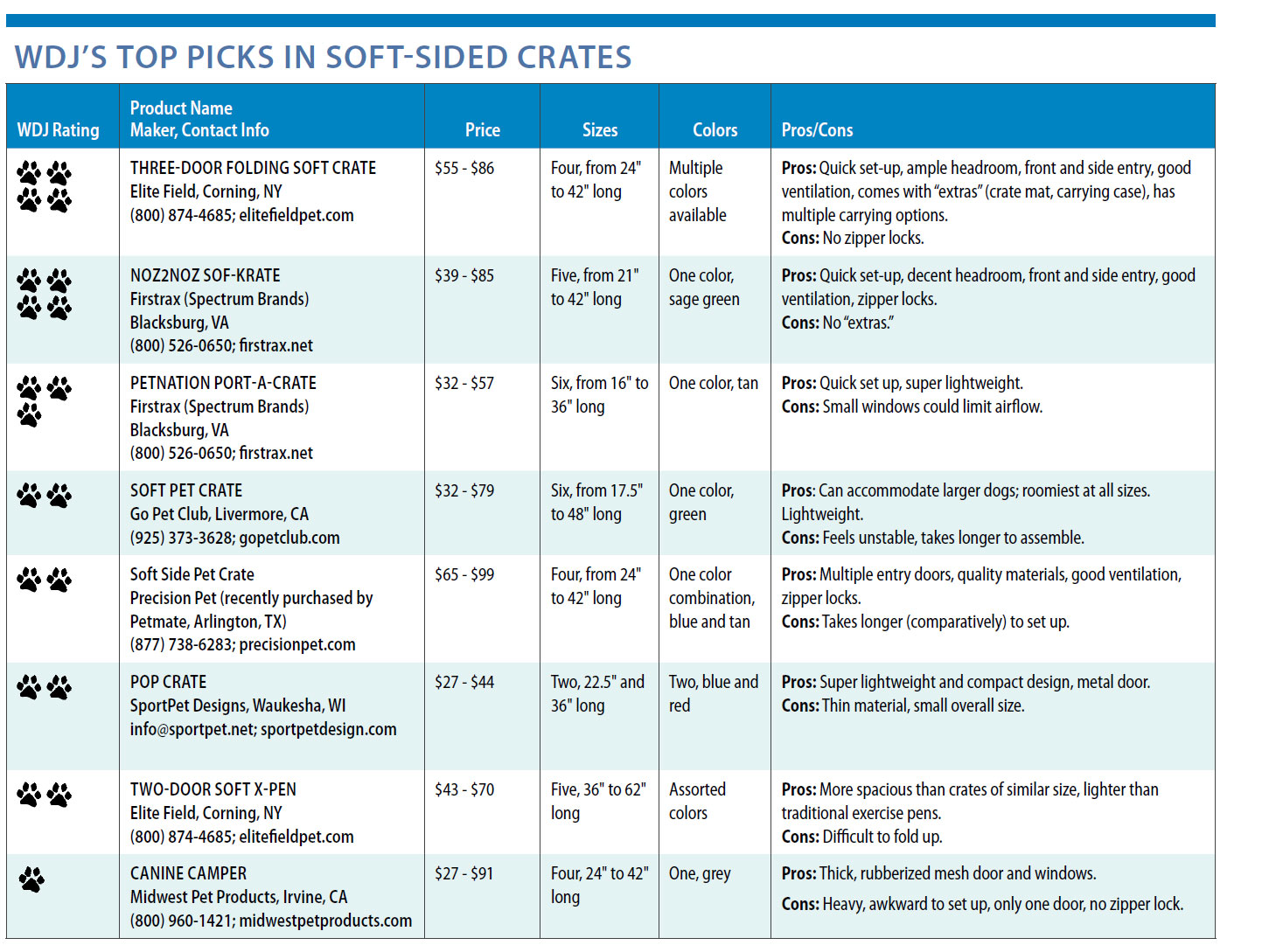

Soft-Sided Dog Crates: Best and Worst